Executive summary

The current generation of pensioners has, in general, been better served by the UK’s mix of state and private pension provision than earlier generations were. Pensioners today have disposable incomes – once you take account of housing costs and children – that on average are similar to those below pension age, as well as lower poverty rates. The risk is that this has led policymakers and commentators to take their eye off the pensions ball. Just because the current generation of pensioners is doing better, that does not mean that will continue for future generations.

There remain challenges that need addressing. The next government needs to take decisions on pensions which are not made easier by the pressures that an ageing population puts on the public finances. In this report we identify five key priorities for whoever is pensions minister after the general election. Some of these issues need decisions soon. A failure to address others would risk storing up greater problems for the future.

Underlying many of the challenges facing many saving for retirement today is a lack of risk sharing. Automatic enrolment into workplace pensions has been a big policy success. But individual bad luck or bad decisions – or a failure to make a decision – can still have significant consequences in a way which was much less true for those who enjoyed old-style defined benefit pensions, benefited from state earnings related pensions, or had no choice but to annuitise their defined contribution pension pot.

Key findings

1. The next government will need to decide whether to provide additional support to those not able to work up to an increased state pension age, and how any such support should be targeted, while considering the effects on work incentives and government spending. This is urgent as the state pension age will rise from 66 to 67 between 2026 and 2028. The government will also have to finalise the timing of the increase in the state pension age to 68. If it chooses to accept the recommendation of a previous independent review to bring the increase forward to the late 2030s, then those directly affected should be notified in the next few years (in line with the current government’s sensible commitment to provide at least 10 years’ notice of any change). Increasing the state pension age is a coherent response to increases in longevity at older ages, and one that other countries are also adopting. But it affects poorer people more, as well as those who find it more difficult to remain in paid work at older ages.

2. A long-term plan is needed for the level of the state pension. The triple lock, which both Conservative and Labour parties have suggested they will maintain, increases the level and cost of the state pension in an uncertain, and ultimately unsustainable, way. Current forecasts suggest maintaining the triple lock will cost around £1.5 billion per year by 2029–30 relative to earnings indexation, although the triple lock could cost less, or (as has been the case in recent years) far more than forecast. A better way forward is possible, where the government decides on the appropriate level of the state pension and then increases it to keep up with average earnings growth in the long run, but also commits to increase it by at least at the rate of inflation every year.

3. The next government needs to decide whether to go ahead with legislated increases in minimum pension contributions. If they do, they should carefully consider the timing, as well as potential alterations to the policy to help low earners adjust to lower take-home pay. The Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act was passed in 2023 but has not yet been implemented by the government. It would extend automatic enrolment to 18- to 21-year-olds and abolish the lower earnings limit for qualifying earnings. This latter change means additional total contributions of £499 per year (including from the employer and tax relief) for people with minimum contributions (8% of qualifying pay). For someone earning £10,000, this would lead to a reduction in take-home pay of at least 2.5% (£250), and likely more depending on how much wages adjust downwards given the policy.

4. The next government should target a long-term policy solution to support pension saving among the self-employed. Low rates of private pension participation for self-employed workers remains an unresolved concern. Around 20% of self-employed workers participate in a private pension, down from 50% in 1998. More employees earning less than £10,000 (and therefore not targeted by automatic enrolment) are saving in a pension (25%) than the self-employed. More needs to be done to make it easier for self-employed workers to save in a private pension (and for those who are already saving to save more), potentially by integrating pension saving into the Self Assessment system for self-employed people.

5. The next government should develop policies to help people draw on their private pension wealth appropriately. This could mean requiring pension schemes to provide people with decumulation pathways, including solutions that combine annuities with accessible savings pots. The government could also require schemes to provide default options, to ensure that these policies also work better for those who don’t engage actively with their pension. This is because, while the ‘pension freedoms’ reforms of 2015 have opened up opportunities for additional flexibility, they also expose more people to longevity risk (running out of private resources due to living longer than expected), and to more difficulties managing their incomes at older age.

Introduction

State and private pensions make up the vast majority of income for those over the state pension age. There is therefore intense political interest in how previous (or proposed) pensions reforms affect pensioners, and in the economic fortunes of older people more generally.

This short report sets out key pensions issues facing the next government. We focus on urgent policy decisions that will need to be taken in the next parliament, in combination with longer-run policy decisions that cannot be put off for long without storing up difficulties for the future. Our report is undertaken as part of ‘The Pensions Review’,1 the IFS project reviewing the future of financial security in retirement in partnership with abrdn Financial Fairness Trust.

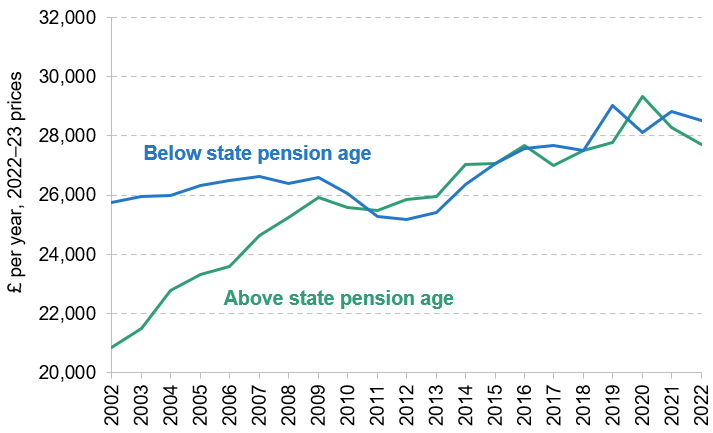

Figure 1 provides important context for this report. It shows median household income for pensioners and non-pensioners over the last 20 years of data. In 2002, median pensioner income was almost 20% below that of working-age people. By 2011, that gap had fallen to zero, and since then, median incomes above and below state pension age have evolved similarly. Pensioner incomes fell in real terms during the cost-of-living crisis, with the state pension rising by only 3.1% in April 2022 while inflation reached over 10% in that year. But between 2022–23 (latest data) and 2024–25 (this year), the real value of the state pension is expected to rise by 11% as inflation falls. At the lower end, 16% of pensioners (1.9 million people) are in relative poverty – i.e. have incomes below 60% of the median. Although this is up from its recent low of 14% in 2014–15, it is considerably below the rate for the working-age population (20%).

In part, the good position of pensioner living standards compared with the rest of the population reflects policy successes, some of which were the result of following the recommendations of the Pensions Commission (2005). As noted by a previous IFS Pensions Review report on the state pension (Cribb et al., 2023a), the UK pension system now has much to commend it: boosts to the flat-rate state pension (which most people reaching state pension will receive the full amount of) provide a strong foundation for retirement incomes. The state pension ensures most new pensioners are not in income poverty (though there are issues for single private renters in high rent parts of the country unless they have private pension income). Between 2018 and 2020, the first universal increase in the state pension age was delivered, and is a mechanism to help contain future costs that arise as a result of increasing longevity at older ages. And in the private sector, automatic enrolment has brought millions of private-sector employees into a workplace pension, and with it receipt of an employer contribution, for the first time.

Figure 1. Real median household disposable income (£, annual, 2022–23 prices), for pensioners and non-pensioners, after deducting housing costs

Note: Incomes measured as net household equivalised incomes, after deducting housing costs, and expressed in 2022–23 prices. Incomes expressed as equivalents for a childless couple.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey, 2002–22.

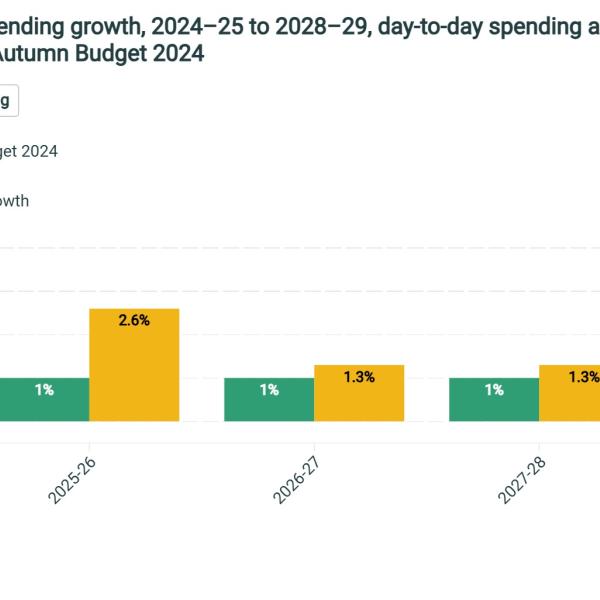

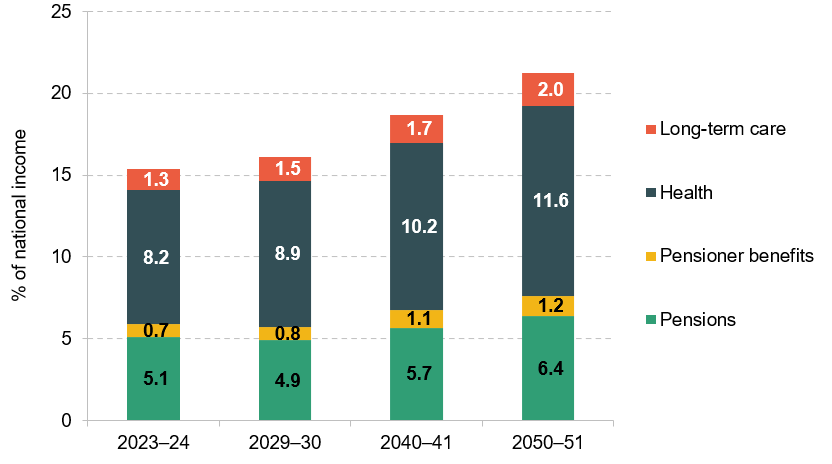

But there are also a number of pressing issues. Declines in the prevalence of defined benefit (often referred to as final salary) pensions, low pension participation for the self-employed, falling homeownership, and other issues mean future generations may be at risk of disappointing levels of income in retirement (Cribb et al., 2023b). And the capacity for the state to provide retirement income is put under pressure by the challenges of an ageing population, as shown in Figure 2. Spending on pensioners (and pensioner benefits), health and social care is forecast to rise from 15.4% of GDP last year to 16.1% in 2029–30, 18.7% in 2040–41 and 21.2% in 2050–51. The largest contributor to this increase is health spending but, from 2030s on, spending on state pensions and pensioner benefits is forecast to rise substantially (but will be held down in the coming parliament by the state pension age rising to 67).

Figure 2. Projected government spending on state pension, pensioner benefits, health and social care, 2023–24 to 2050–51

Note: ‘Pensions’ includes winter fuel payment and pension credit. ‘Pensioner benefits’ is all other benefits paid to people over state pension age (such as attendance allowance, disability living allowance and housing benefit).

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility (2023).

In light of these successes and challenges, this report discusses some of the key policy questions the incoming government will have to tackle. We first set out two key issues facing the state pension system. We then examine three decisions needed regarding the private pension system. The conclusion notes that there is a range of other issues in the pensions landscape that interact with the challenges we identify.

Policy issues facing the state pension

State pensions make up 43% of pensioner incomes on average, including 71% of income for the poorest 20% and 23% for high-income people (top 20%) (Cribb et al., 2023a). Government spending on the state pension, pension credit and winter fuel payment was £132 billion, or 5.1% of national income, in 2023–24. The 5.1% compares with 5.0% of national income spent on these payments in 2009–10 – the rise having been limited by significant rises in the state pension age. Taking into account other pensioner benefits as well, total benefit spending on pensioners was 5.5% of national income in 2023–24, compared with 4.6% of national income spent on benefits for working-age adults and children. In other words, 55% of total benefit spending in 2023–24 was to pensioners, up from 52% in 2009–10.

Given the pressures of an ageing population, there is a need to think about mechanisms for controlling costs. The key ones are increases in the state pension age, and the level of the state pension and how it is indexed.

1. Navigating increases in state pension age: 67 and beyond

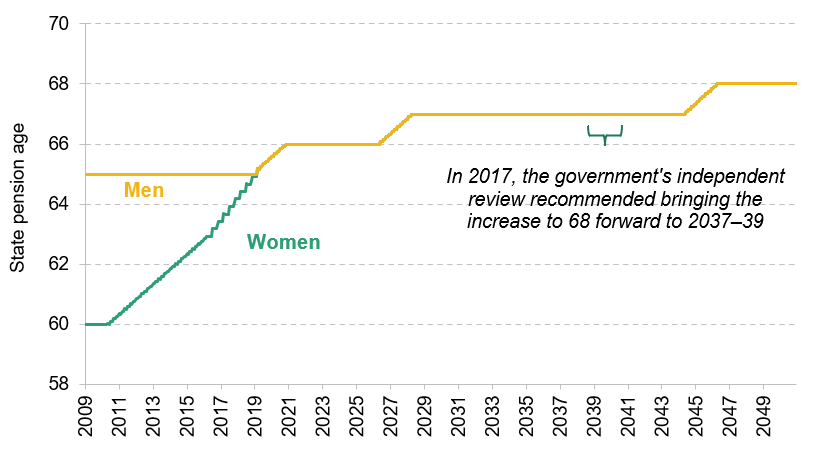

The state pension age, the age from which people can start claiming their state pension, increased from 60 to 65 for women between 2010 and 2018, and increased from 65 to 66 for men and women between 2018 and 2020. Two further increases are currently legislated: from 66 to 67 between 2026 and 2028, and again from 67 to 68 between 2044 and 2046.

While increasing the state pension age is a coherent response to public finance pressures arising from increased longevity at older ages, there are also concerns around those who struggle to work up to (a rising) state pension age. Previous IFS research (Cribb and O’Brien, 2022) shows that the increase in the state pension age from 65 to 66 increased the income poverty rate of 65-year-olds by 15 percentage points. Concerns about low living standards below state pension age have been raised by various groups (Phoenix Insights, 2023; Fabian Society, 2024).

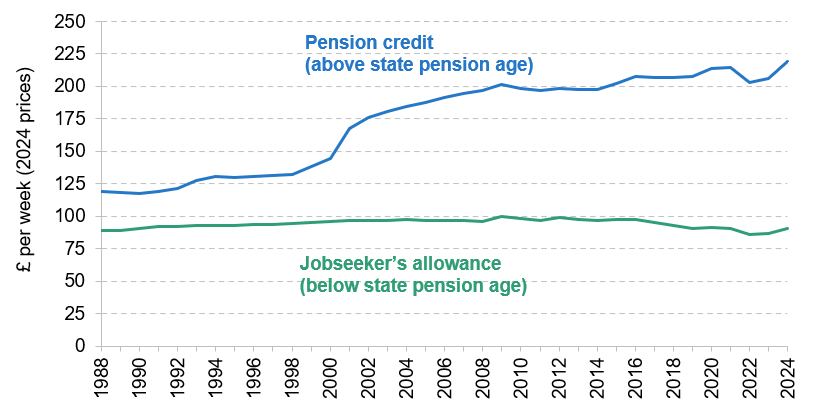

One reason for this issue is the large gap in basic state support available to those out of paid work above and below state pension age (Figure 3). This gap has increased over time, with pension credit 40% higher than jobseeker’s allowance in 1997, 103% higher in 2010, and 142% higher in 2023, though there are issues with low take up of pension credit, meaning that many pensioners who are eligible for this support actually receive it (see House of Commons Library 2020). With the next increases in state pension age starting in Spring 2026, a key question for the next government will be to determine whether or not to provide more support to those not able to work up to state pension age, and if so, how that support should be targeted. Any additional support would need to be balanced against potential weakening of the incentive to stay in paid work and, of course, the resulting increase in public spending. In the long run, some additional support may be important to ensure that increases in state pension age are a feasible way to limit the cost of the state pension.

The next government will also have to decide on the timing of the increase in the state pension age to 68. In current legislation, the rise to 68 will happen between 2044 and 2046. The Independent Review of the State Pension Age (Department for Work and Pensions, 2017) recommended bringing that forward to 2037–39 (see Figure A1 in the Appendix), although much has changed since 2017 – in particular, generation-on-generation rises in longevity have not been as fast as expected (see Cribb et al., 2023d) Given the government has, sensibly, previously committed to giving affected people at least 10 years’ notice ahead of any state pension age increase, as recommended by the Independent Review, if the next government wants to bring forward the rise to 68, those directly affected would need to be notified in the next few years. The next government may also want to start considering the case for state pension age increases beyond 68; the increase to 68 was legislated 17 years ago in 2007.

Figure 3. Entitlements for pension credit and jobseeker’s allowance, 2024 prices, 1988–2024

Note: Real levels in April of each year are shown. Entitlements shown for single adults. Note that other forms of support are available to low-income people who are out of work above and below pension age, such as housing benefit. Adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Prices Index (CPI).

Source: Authors’ calculations using ONS series D7BT (for the CPI; https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/ inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/d7bt/mm23), Abstract of DWP benefit rate Statistics 2023 (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/abstract-of-dwp-benefit-rate-statistics-2023) and https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-and-pension-rates-2024-to-2025/benefit-and-pension-rates-2024-to-2025#pension-credit.

2. Level of the state pension: need for a long-term plan

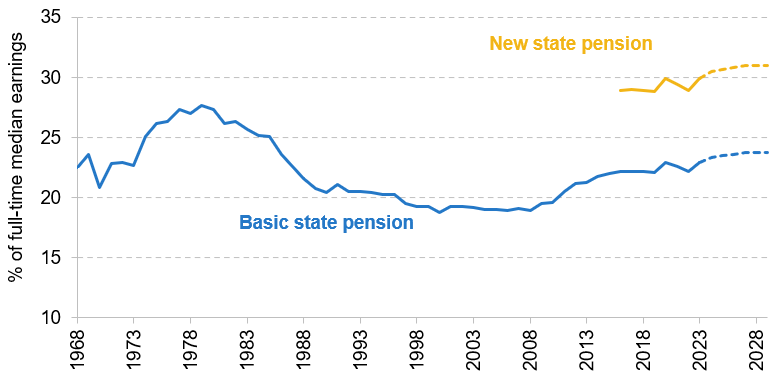

How the government increases the level of the state pension over time is the other key parameter for the state pension system. In 2011, the Coalition government introduced the ‘triple lock’ for the basic state pension (rising in line with the highest of inflation, earnings growth, or 2.5%)¬. The new state pension was then introduced for those reaching state pension age after April 2016. Together this means that the flat rate state pension is now worth 30% of median full-time earnings (see Figure 4), which is higher than it has ever been since the start of our data in 1968.

Indexation may not seem like an issue for the top of the government’s agenda, with inflation falling and recovery from the cost-of-living crisis under way. However, the latest OBR forecasts imply that uprating the state pension by the triple lock during the next parliament would cost around £1.5 billion per year (in today’s prices) by 2029–30 compared to earnings indexation. While it could cost less than that if real earnings growth is strong, it could easily cost more. OBR forecasts prior to the 2019 general election suggested the triple lock would cost nothing compared to earnings indexation, but in fact it pushed up spending by around £3.2 billion this year alone. Before the 2015 general election, OBR forecasts suggested it would push up spending by only £0.2 billion per year (in today’s prices) by 2019–20 but the triple lock actually increased spending by £0.9 billion per year. The more volatile are earnings and inflation, the more the triple lock would push up the value of the state pension, and the more it would cost – since its introduction, the state pension was indexed in line with 2.5% in four out of 14 years, and in line with inflation in six out of those years (Cribb et al., 2023c). The triple lock therefore creates uncertainty for both the level of pension (compared to average earnings) and for the public finances.

Figure 4. Basic and new state pension over time relative to median full-time earnings, 1968–2029 (2024–29 forecast represented by dashed lines)

Note: Median full-time earnings since 1984 are from Department for Work and Pensions benefit rate statistics; values for earlier years are calculated using the growth rate of nominal full-time median earnings from the Family Expenditure Survey. The values from 2024 onwards are calculated using the predicted triple lock and average earnings growth figures from the OBR’s long-term economic determinants table from March 2024.

Source: Abstract of DWP benefit rate Statistics 2023 (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ abstract-of-dwp-benefit-rate-statistics-2023), OBR’s Supplementary forecast information release: long-term economic determinants – March 2024 (https://obr.uk/supplementary-forecast-information-release-long-term-economic-determinants-march-2024/) and authors’ calculations.

This also highlights that it is not just the state pension age that matters for the cost of the state pension, but also the level of the state pension. Controlling costs through a higher state pension age alone, with more generous indexation, tends to benefit current pensioners (who have already reached state pension age) and richer people (who have longer life expectancy and so receive the state pension for longer) as compared to poor working-age people (Cribb et al., 2023a).

The triple lock causes problems because it ratchets up the level, and cost, of the state pension in a way that would become unsustainable in the long run. And it does so by increasing its value in particular in volatile economic times. At some point, a government will have to take a view on how generous the state pension should be and introduce a credible indexation system that creates a more predictable path for the future. The earlier this is done the better. The four-point pension guarantee, suggested as part of the IFS Pensions Review in December 2023 (see Cribb et al., 2023a), would be a good way of doing this, with the key elements here being that once a target level for the state pension is reached2, the state pension would rise in line with earnings in the long run, but it would also provide protection against inflation, with the state pension rising at least in line with inflation every year.

Policy issues facing private pensions

Although the state pension is an important source of retirement income for most pensioners, many workers will need to accumulate private wealth during working life to prevent a large fall in living standards at retirement. This is most obviously done through a private pension. Policies should aim to ensure that both employees and the self-employed make good decisions about saving into private pensions, as well as good decisions about drawing down pension wealth in retirement. We set out three key issues for the next government regarding private pensions.

3. Making automatic enrolment work better for employees

Due to concerns about falling pension participation among employees, between 2012 and 2018 automatic enrolment into workplace pensions was rolled out. This led to a doubling in the share of eligible (those earning over £10,000, aged 22 to state pension age, and who were employed for more than three months) private-sector employees saving into a pension, from 40% in 2012 to 76% in 2022. Despite the success of automatic enrolment in encouraging pension participation among employees, there are still causes for concern around the private pension saving of employees.

Many employees are saving low amounts in their pensions. The minimum default total contribution rate under automatic enrolment is 8% of ‘qualifying’ earnings: between the lower level of qualifying earnings (£6,240) and the upper level (£50,270). As a result, many employees are automatically enrolled with quite low contribution rates – indeed, over half of private-sector employees saving in a workplace pension have total contributions of less than 8% of gross earnings (Cribb et al., 2023b). While analysis by the Department for Work and Pensions (2023b) found that the majority of employees are likely to be saving enough for retirement, there is still a significant minority (around 38%) who are projected to be under-saving.

In response to concerns about under-saving, the Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act 20233 introduced powers for the Secretary of State of Work and Pensions to be able to reduce the lower eligibility age for automatic enrolment from 22 to 18, and to increase minimum pension contributions by reducing the lower limit on qualifying earnings to zero (rather than £6,240 currently). To be clear, this latter change does not mean that all employees will have to be automatically enrolled (that still only applies to those earning over £10,000), but rather those who are enrolled will save – at a minimum – 8% of all their earnings (up to an upper limit), rather 8% of earnings above £6,240 (up to an upper limit). The Secretary of State has not yet brought these changes in.

Reducing the lower limit on qualifying earnings to zero would mean an additional contribution of £499 per year for all people on minimum contributions (8% of qualifying earnings) if implemented this year, thereby boosting their retirement saving. Assuming these people receive the minimum employer contribution, £187 of this would come from the employer, £250 would come from the employee, and £62 from tax relief. This will have the largest impact on the lowest earners who are automatically enrolled. For someone earning £10,000 per year (the most affected group), this would result in increasing minimum contributions by over 160%, and would reduce take-home pay by around 2.5%. Over time we would expect the reductions to be larger as employers adjust wages downwards in response to higher remuneration through employer pension contributions.

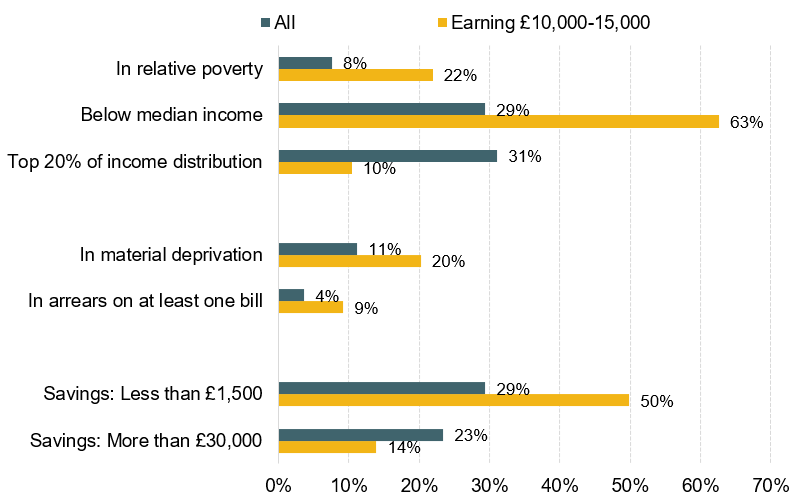

Given the reductions in current incomes resulting from higher pension contributions, it is important for government to consider retirement saving alongside other financial priorities. These priorities can range from people aiming to pay down debt, building up savings in more accessible forms, or consuming more today. Figure 5 examines characteristics of employees saving in a workplace pension, earning between £10,000 and £15,000 per year, who would be most affected by moving contributions to the first pound, compared with all employees participating in a workplace pension. Employees earning £10,000 to £15,000 have varying financial situations, with 22% in relative poverty, but 10% in the top fifth of the household income distribution (most obviously because they have a higher earning partner). However, employees earning in this range are generally concentrated in the bottom half of the household income distribution. In addition, many seem to have other demands on their income: we find that 20% are in material deprivation (that is, unable to afford essential goods and services), while 9% are in arrears on at least one bill. Half of this group have accessible savings of less than £1,500, which may make them vulnerable to unexpected expenses or falls in income.

Figure 5. Characteristics of employees who are participating in a workplace pension scheme, 2022–23 (All; and employees earning £10,000 to £15,000)

Note: Incomes measured after deducting housing costs. Relative poverty line is 60% of median income.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey, 2022–23.

The next government therefore needs to decide how best to adjust automatic enrolment in order to help people save appropriately for retirement. Implementing the Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act 2023 would increase pension contributions, particularly affecting lower earners who are likely to have other demands on their current incomes. If implemented, the government should carefully consider the timing of such an increase, consider whether any adjustments to the Act are needed, or whether other policies should be introduced in parallel to help people adjust to lower take-home pay. For example, there have been proposals to direct some pension contributions initially in accessible workplace saving accounts, to help lower earners build up rainy-day savings (Nest Insight, 2023; Broome, Mulheirn and Pittaway, 2024). Regarding timing, one option would be to increase minimum contributions gradually in stages over a few years rather than make a single larger change.

4. Addressing low pension saving among the self-employed

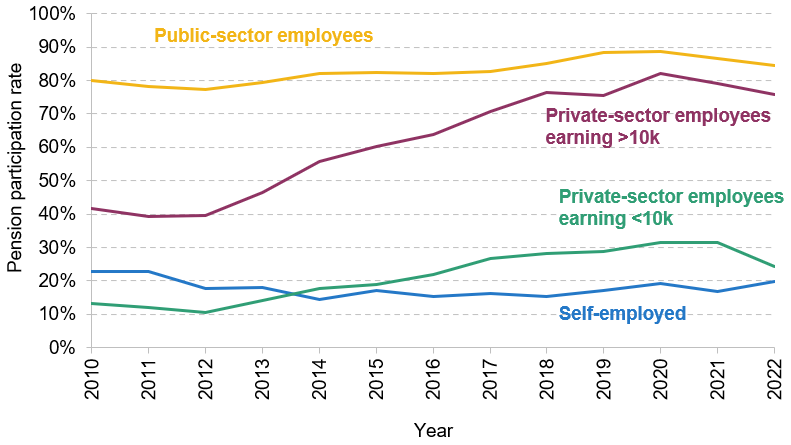

One group that has not benefited from the successes of automatic enrolment is the self-employed. Figure 6 shows that pension participation rates for self-employed workers are at a very low level (around 20%). This compares to a pension participation rate of around 50% back in 1998. In contrast, pension participation rates are around 85% among public-sector employees and almost 80% among private-sector employees in the target group for automatic enrolment. Even private-sector employees earning under £10,000, and therefore not directly targeted by automatic enrolment, are more likely to be in a pension (24%) than the self-employed.

Therefore, concerns remain that the private pension system is not working well for the self-employed, despite this group making up around 15% of the workforce. This issue was not resolved by the Pensions Commission, nor has it been tackled since. The fundamental difficulty is that it is impossible to implement automatic enrolment for the self-employed in the same way as it is for employees, given that, by definition, they do not have an employer to enrol them.

There are potential solutions on the horizon. Nest Insight (2022) conducted a variety of trials showing there are ways that could improve the system for the self-employed, for example, by making it easier for those who move from employment to self-employment to continue saving into their old workplace pension, or by incorporating nudges to save into accountancy software already used by many self-employed workers. There are also possibilities for integration of pension saving into the Self Assessment system that could also reduce barriers to saving for the self-employed.

Figure 6. Pension participation over time for public- and private-sector employees and the self-employed

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey, 2010–11 to 2022–23.

Given the challenge of low levels of pension saving by self-employed workers, and the possibilities of new solutions, the next government should target a long-term policy of encouraging private pension saving among the self-employed, so that we are not still having the same conversation about the retirement saving of the self-employed when the next election comes around.

5. Managing retirement incomes: how to encourage good decisions

In 2015, the government removed the requirement for anyone to have to purchase an annuity (an ‘income for life’) with their accumulated defined contribution pension pot, a policy known as ‘pension freedoms’. People who have saved into defined contribution pots can now draw on this pension wealth as they wish. Combined with the decline of traditional defined benefit pensions (which also provide an income for life) and the rise in defined contribution schemes, an increasing number of people face complex financial decisions at, and during, retirement.

Individuals now have to decide how to balance the desire to draw a regular income (potentially insuring themselves against living longer than expected by purchasing an annuity), against keeping more of their resources in accessible form. The right decision for each individual will depend on a number of factors such as their appetite for risk, how long they expect to live, other resources available to them and their partner/spouse, and whether they have a strong preference to keep wealth in an accessible form, for example to help fund social care costs later on.

Pension freedoms benefit especially those who would like to keep their savings in an accessible form, want to spend more earlier on in retirement, or who were worried about ‘locking-in’ low annuity rates during the 2010s. But the greater choice also comes with a number of risks, including being more exposed to longevity risk (which could lead to people running out of private resources or being needlessly austere when faced with this risk). Many people may now have to make financial decisions regarding their pensions well into old age, at a time when cognitive function can start to decline. The next government should consider policies aimed at helping people with these decisions to help prevent the most adverse outcomes. This should include policies that work well for the many people who are unlikely to understand pensions or to engage actively with the pension system.

One of the suggestions from a 2023 government consultation on pension freedoms (Department for Work and Pensions, 2023a) was for pension schemes to offer a ‘decumulation’ service with product options and to have a default solution for those who do not engage with their pension. The consultation responses highlighted that most people would like a hybrid solution for accessing their pensions – keeping some of their pot in an accessible form, while purchasing an annuity with another part. Pension schemes could be required to offer such hybrid solutions to those wanting to access their pension, in addition to the more traditional products already available.

The legislation that will allow multi-employer collective defined contribution (CDC) schemes is also in the process of moving forward. Getting this legislation over the line is likely to be important as it could allow for ‘decumulation’ solutions where some of the longevity risk that individuals face is pooled. Though – as ever – care needs to be taken to ensure that where risks are being transferred, these are understood and well managed. In the meantime, introducing stronger nudges for people to use the guidance that is provided free of charge by the government (Pension Wise), and paid advice where appropriate, may also help protect people from the worst outcomes, such as being subject to scams and fraud or taking other obviously wrong options.

Having a better system to help people manage their incomes in retirement is growing in importance. Following automatic enrolment, each cohort of new retirees is more likely to have significant defined contribution pension wealth. Immediate solutions are not (yet) critical. But long-term solutions are needed. It will be critical in the next parliament to make progress on this issue to help people manage their incomes in retirement, allowing people to benefit fully from their savings.

Concluding discussion

This report has highlighted five key pensions policy areas that will be at the top of the inbox of the incoming government after the election. This is not an exhaustive list – there are a number of other long-term issues, especially in the private pension space, that need resolving. Issues with the proliferation of pension pots and the Chancellor’s ‘pot for life’ proposal,4 the ‘Mansion House reforms’,5 designed at increasing the share of defined contribution pension assets invested in unlisted UK equities, and the introduction of Pension Dashboards6 (allowing people to view all their pension savings on one platform) are all examples of pensions policies where implementation has not yet been completed or of proposals that are worthy of further consideration. And there remains a debate about the appropriate taxation of private pensions (see Adam et al. (2024) for a previous IFS election-related report on this topic).

Alongside the long list of related issues, the challenges facing private pensions we have set out – making sure automatic enrolment is delivering good outcomes for employees, addressing low pension saving among the self-employed, and providing more support to people accessing their pension pots – are especially important given the considerable financial risks that people face in the current system. More and more people save in defined contribution (rather than defined benefit) pensions and fewer people purchase annuity products. People therefore have to make important decisions about how much to save and how to draw on their wealth, while faced with uncertainty about how their investments will perform and how long they might live. Policies supporting people to make sensible decisions given these risks are therefore of the essence.

On the state side, the decisions regarding the state pension age and the level of the state pension age may seem separable. In fact, what is needed are decisions to be made together, setting out the government’s view on the appropriate level of state support for older people. A good way forward for the state pension would be for the government to commit to a long-term target for the level of the state pension, a key feature of the IFS Pensions Review’s four-point pension guarantee discussed earlier. Ideally, alongside this, the government should also consider the appropriateness of the benefit system for people approaching, and after, state pension age.

Setting pensions policy is difficult. It is slow moving, as the outcomes of policy changes today may only become apparent decades later, when people affected reach retirement. While the current system has many good features, and outcomes for today’s pensioners are certainly better than they were for earlier generations of pensioners, there is also a set of challenges that we have identified in this report. Some of these issues need decisions soon. A failure to address others would risk storing up greater problems for the future. Either way, it is particularly important that a government making decisions on pensions does so in a cohesive way that considers the whole of the pension system together to deliver good outcomes for today’s savers and tomorrow’s retirees.

Appendix: supplementary chart

Figure A1. State pension age for men and women under current legislation, 2009–50

Note: Since 2019, the state pension age for men and women has been the same.

Source: Department for Work and Pensions ‘State Pension age timetable’, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/state-pension-age-timetable/state-pension-age-timetable.

References

Adam, S., Delestre, I., Emmerson, C. and Sturrock, D. (2024). Should the pensions lifetime allowance be reintroduced and, if so, how? IFS Comment, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/should-pensions-lifetime-allowance-be-reintroduced-and-if-so-how.

Broome, M., Mulheirn, I. and Pittaway, S. (2024). Precautionary tales: tackling the problem of low saving among UK households. Resolution Foundation report, https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2024/02/Precautionary-tales.pdf.

Cribb, J., Emmerson, C., Johnson, P. and Karjalainen, H. (2023a). The future of the state pension. IFS Report R291, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/future-state-pension.

Cribb, J., Emmerson, C., Johnson, P., Karjalainen, H. and O’Brien, L. (2023b). Challenges for the UK pension system: the case for a pensions review. IFS Report 255, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/challenges-uk-pension-system-case-pensions-review.

Cribb, J., Emmerson, C. and Karjalainen, H. (2023c). The triple lock: uncertainty for pension incomes and the public finances. IFS Report R272, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/triple-lock-uncertainty-pension-incomes-and-public-finances.

Cribb, J., Emmerson, C., Karjalainen, H., O’Brien, L. and Sturrock, D. (2023d). The planned increase in the state pension age from 67 to 68. IFS Comment, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/planned-increase-state-pension-age-67-68.

Cribb, J. and O’Brien, L. (2022). How did increasing the state pension age from 65 to 66 affect household incomes? IFS Report R211, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/how-did-increasing-state-pension-age-65-66-affect-household-incomes.

Department for Work and Pensions (2017). Independent Review of the State Pension Age: smoothing the transition. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a81eb22ed915d74e3400c27/print-ready-independent-review-of-the-state-pension-age-smoothing-the-transition.pdf.

Department for Work and Pensions (2023a). Helping savers understand their pension choices: supporting individuals at the point of access: consultation response. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/helping-savers-understand-their-pension-choices-supporting-individuals-at-the-point-of-access/outcome/helping-savers-understand-their-pension-choices-supporting-individuals-at-the-point-of-access-consultation-response#chapter-10-conclusion.

Department for Work and Pensions (2023b). Analysis of future pension incomes. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/analysis-of-future-pension-incomes/analysis-of-future-pension-incomes.

Fabian Society (2024). When I’m 64: a strategy to tackle poverty before state pension age. Fabian Society Policy Report, https://fabians.org.uk/publication/when-im-64/.

House of Commons Library (2020). Pension Credit – current issues, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8135/.

Nest Insight (2022). Exploring practical ways to support self-employed people to save for retirement. https://www.nestinsight.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Exploring-practical-ways-to-support-self-employed-people-to-save-for-retirement.pdf.

Nest Insight (2023). Workplace sidecar saving in action. https://www.nestinsight.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/workplace-sidecar-saving-in-action.pdf.

Office for Budget Responsibility (2023). Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2023. https://obr.uk/frs/fiscalrisks-and-sustainability-july-2023/.

Pensions Commission (2005). A new pension settlement for the twenty-first century: the second report of the Pensions Commission. The Stationery Office, https://archive.org/details/newpensionsettle0000unse.

Phoenix Insights (2023). An intergenerational contract: policy recommendations for the future of the state pension. https://www.thephoenixgroup.com/phoenix-insights/publications/future-of-the-state-pension/.

Data

Department for Work and Pensions, NatCen Social Research. (2021). Family Resources Survey. [data series]. 4th Release. UK Data Service. SN: 200017, DOI: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-200017.