In our report on the Scottish Government’s Budget for 2024–25, we examined in detail how higher education in Scotland is funded, and some of the challenges facing universities and students. As we will discuss more fully in an upcoming report ahead of the Scottish Budget for 2025–26 on 4 December, the overall funding situation for the Scottish Government may have improved, but there remain difficult decisions to be made on higher education funding. We here update some key figures, and highlight some emerging challenges for the finances of Scottish universities.

University finances

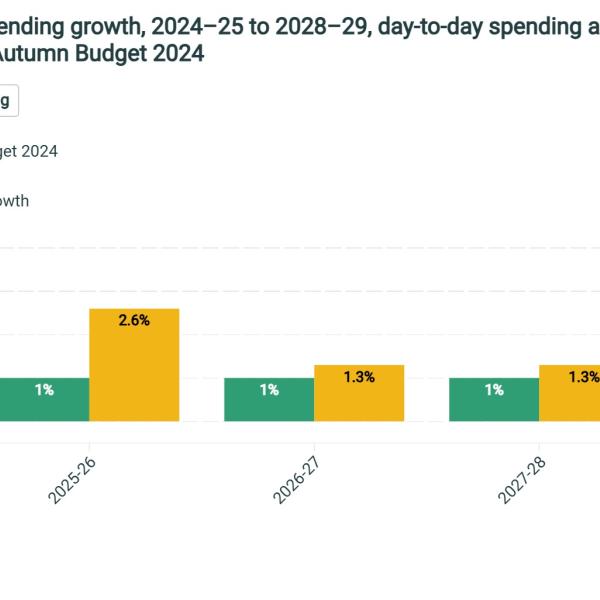

In the year to July 2023 – the most recent covered by HESA finance data – Scottish universities appeared to be in reasonable financial health. After adjusting for mostly one-off pension effects, the vast majority were in surplus (with income exceeding their expenditures) and the surplus was worth on average 5.2% of their income. This was lower than the sector-wide surplus the previous year (9.9%) although it was similar to the modest surpluses typical in Scotland before 2020–21 and it remained larger than the same figure for universities in England (3.7%).

Figure 1. Average surplus for English and Scottish universities, by academic year

Note: We include only the subset of universities in Scotland which appear in every year of the finances data from 2015–16 to 2022–23 to allow for consistent comparisons over time. Surplus is total income less expenditure, where expenditure figures are adjusted to remove the impact of pension cost adjustments. Average is weighted by provider income.

Source: Author’s calculations using HESA finance data (various years). Methodology, and figures for England, from Ogden and Waltmann (2024).

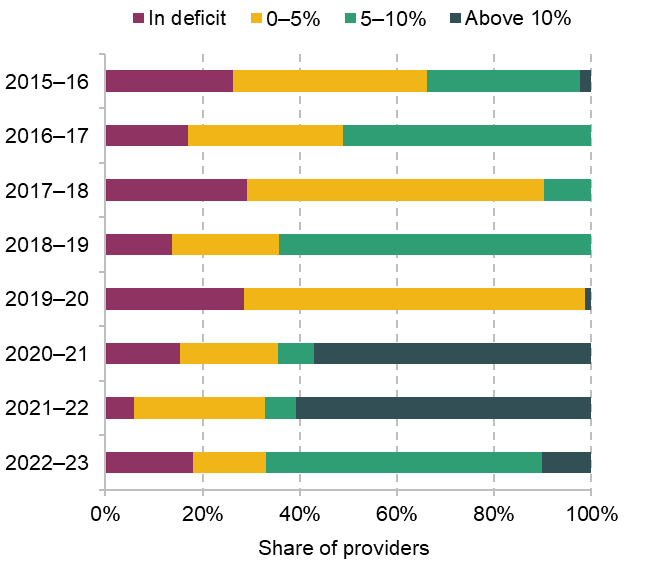

These trends – rising surpluses after 2019–20 and falling surpluses in 2022–23 – can also be seen looking at the distribution of surpluses across the sector. In 2022–23, just under a fifth of Scottish universities (weighted by income) had an in-year deficit, which was similar to the typical share before the pandemic.

Figure 2. Distribution of in-year surpluses of Scottish universities, by academic year

Note: See note and source to Figure 1. Share of providers is weighted by provider income.

However, there are two reasons to be concerned that the finances of the sector may have worsened further since: changes in the funding available for teaching home undergraduates, and likely falls in international student recruitment.

Resources for teaching home undergraduates

The resources available to Scottish universities specifically to teach Scottish undergraduate students are made up of a ‘tuition fee’ paid on behalf of most Scottish undergraduate students by the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS) and grant funding distributed to universities by the Scottish Funding Council. The tuition fee for home fee students remained flat in cash terms in 2024–25 at £1,820 – remarkably the fifteenth year in a row that it had been at that same cash level. The Scottish Government’s 2024–25 Budget included a year-on-year cash decrease in the university resource budget for financial year 2024–25 of £28.5 million (–3.6%, or –5.8% in real terms). As we described back in February, this cut was shared between cuts to per-student resources, and cuts to the number of ‘funded’ places for Scottish students.

In May, the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) confirmed that cuts to the number of funded places would be smaller than many had feared. An additional 1,289 places had been introduced in 2020–21 to meet additional demand from students who had gained the required SQA qualifications after results were revised in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Scottish Government had committed to funding this larger student cohort through their studies, but these additional courses have now largely been completed and the places removed. The SFC had received guidance from the Scottish Government that no additional places should be removed in the 2024–25 academic year. The loss of these funded places accounts for around £7 million of the cut in the main teaching grant for 2024–25 – which has been set at £681.9 million, a reduction of £17.6 million (–2.5%, or –4.8% in real terms) year on year. However, this leaves a substantial reduction in teaching grant per student amongst the remaining funded places.

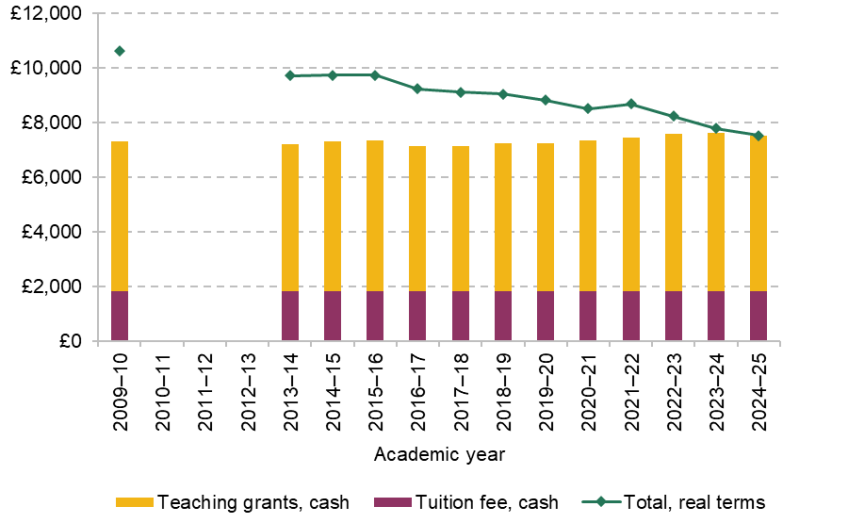

Overall, this means Scottish universities will receive direct public funding of around £7,530 per student for teaching Scottish undergraduates in 2024–25. This represents another real-terms decline in per-student resources. As shown in Figure 3, using an economy-wide measure of inflation, they will receive 22% less per student this academic year than in 2013–14. More than half of this fall has been over the last three years.

Figure 3. Up-front per-student resources for teaching per year

Note: Tuition fee for ‘home fee’ full-time first degree student from SAAS, plus main teaching grant divided by the number of ‘funded’ places. Data not available for years 2010–11 to 2012–13. Real-terms figures based on financial year GDP deflator, and are in 2024–25 prices.

Source: Scottish Funding Council’s university final funding allocations (various years); https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-october-2024-autumn-budget-2024.

Will this trend of declining resources continue? The ‘tuition fee’ for next academic year is yet to be confirmed, but is expected, once again, to stay at £1,820. Changes in the ‘HE Resource’ budget line, which the main teaching grant sits within, in the 2025–26 Budget will indicate what might happen to teaching grants next academic year. Keeping the number of funded places fixed and maintaining real-terms per-student resources at 2024–25 levels would require a cash-terms increase of around £16 million (2.4%). Going further and restoring per-student resources to 2021–22 levels in real terms would require a cash-terms increase in resources of £103 million (15.2%).

International students

Another major risk to university finances stems from a likely decline in international student recruitment. Fee income from international students has become increasingly important for the finances of many UK universities including those in Scotland, particularly as real-terms resources for domestic undergraduates have declined. In 2022–23, Scottish universities had total higher education teaching resources of around £2.7 billion.1 Of this, just over half was from tuition fees charged to students from outside the EU, up from 30% in 2016–17. The substantial growth in non-EU students has been heavily concentrated amongst postgraduates, with fee income from full-time postgraduates worth around £680 million in 2022–23 (26% of all teaching resources).2

Published data on student numbers currently extend to 2022–23, but there is widespread concern that changes to visa rules will have led to declines in international recruitment since. In the 10 months to October 2024, there were 16% fewer applications for visas to study in the UK than in the same period in 2023, and 14% fewer than in 2022.3 Although these visas are for study anywhere in the UK, we might expect the same drivers – especially restrictions on the ability of some students to bring dependants – to have dented demand for study in Scotland.

If there have been falls in international student numbers, they are most likely to be amongst postgraduates. A small year-on-year increase (4.3%) in acceptances of non-EU applicants through UCAS for entry in the 2024–25 academic year suggests that international recruitment of undergraduates to Scottish universities has held up well.4 However, there were 16% fewer entry clearance visas granted for masters-level study in the first six months of 2024 than in the same period in 2022 (and 29% fewer than in 2023). The largest falls were amongst students from Nigeria (–70%), Bangladesh (–69%) and India (–22%).5

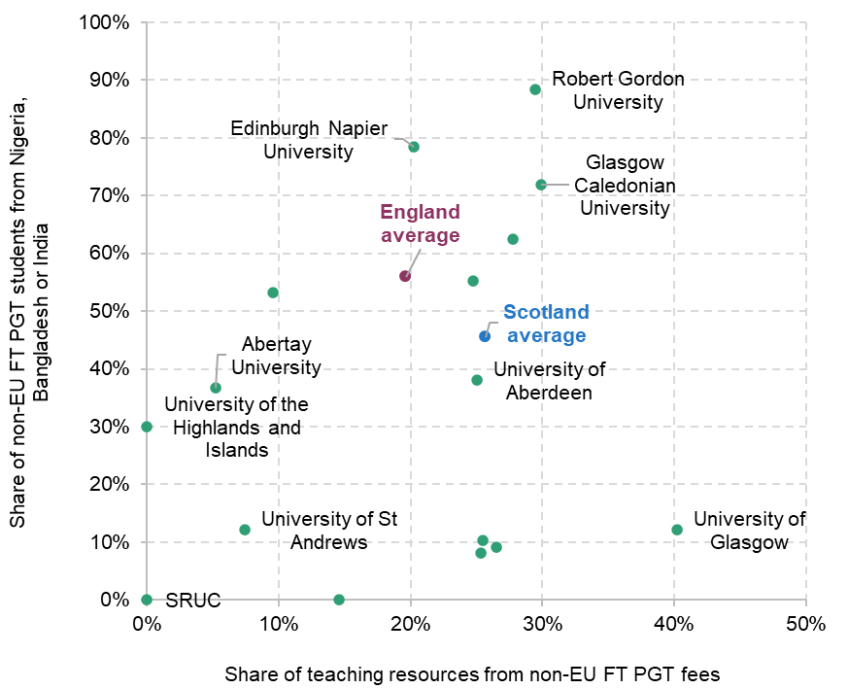

Although these data do not yet cover the summer period (July–September), when the majority of visas for students starting courses in the 2024–25 academic year would typically be granted, these early indications suggest that some Scottish universities may be particularly financially exposed. In 2022–23, fee income from full-time, non-EU postgraduate taught students accounted for more than a quarter of teaching resources at several universities, and for 40% at the University of Glasgow. As shown in Figure 4, the share of such students who were from the three countries that may have seen particularly large falls in numbers was particularly high at three Scottish universities: Robert Gordon University, Edinburgh Napier University and Glasgow Caledonian University. While official data on university finances and student enrolments may not be available for a few years, universities themselves will have been anxiously counting how many students turned up for courses this autumn.6

Figure 4. Share of teaching resources from tuition fees charged to non-EU full-time postgraduate taught students, and share of these students who were from Nigeria, Bangladesh or India in 2022–23

Note: Teaching resources includes ‘Total HE course fees’ and ‘General fund teaching grants’. Two providers where finance data are not available for 2022–23 (Heriot-Watt University and the University of the West of Scotland) are not shown on the chart, but imputed figures are included in Scotland average.

Source: Analysis using HESA student data (DT051 Table 28) and HESA finance data (DT031 Table 6 and DT031 Table 7c).

Headwinds and tailwinds from London

Two other pieces of news from the new UK government will impact the finances of Scottish universities in the coming years.

The first was an announcement from the new Secretary of State for Education, Bridget Phillipson, that the maximum tuition fee for English students will increase in 2025–26 from £9,250 to £9,535 (+3.1%). This ends a long-running cash freeze in the fee cap, which had been increased only once in cash terms since 2012 (from £9,000 to £9,250 in 2017). Compared with a continued freeze, the increase in fees will spare universities in England a further real-terms cut to teaching resources of around £390 million next academic year. If Scottish universities follow suit and increase the fees they charge to students from the rest of the UK, and if they apply this to existing students (not just those starting courses from 2025–26), this might be worth £5–7 million in cash next academic year to universities in Scotland, compared with an ongoing freeze.7

The second piece of news was a hike in employer National Insurance contributions announced at the UK Budget, which will add an average of 2.1% to employment costs from April 2025 (and a higher percentage than this for lower-earning employees). Universities Scotland has estimated the impact of this on Scottish universities at £45 million. Based on back-of-the-envelope calculations, this seems a reasonable figure. For instance, Scottish universities’ staff costs in 2022–23, adjusting for one-off pension costs, amounted to around £2.7 billion. If the pay distribution of staff at Scottish universities was the same as the average across the UK, an additional 2.1% could add £57 million to their paybill (although if the average pay of university staff were higher, with more full-time employees, the cost would be lower, and vice versa).

In the long run, much of the additional tax is expected to fall on employees in the form of wages growing more slowly than they otherwise would have done. But it will take time for wages to adjust, so that the immediate cost impact is likely to fall on universities rather than their staff. We do not expect universities in England to receive explicit compensation as they are not classed as part of the public sector. The Scottish Government will receive some consequentials from the wider public sector compensation in England and could choose to use this income differently.

To avoid further real-terms cuts to per-student funding and offset the higher employer National Insurance bills facing Scottish universities (and taking the lower estimate of the latter from Universities Scotland), the Scottish Government could need to increase grant funding by around £60 million at the upcoming Budget. If extra resources are not forthcoming, then Scottish universities will again be asked to do the same or more for less.

Living cost support for students

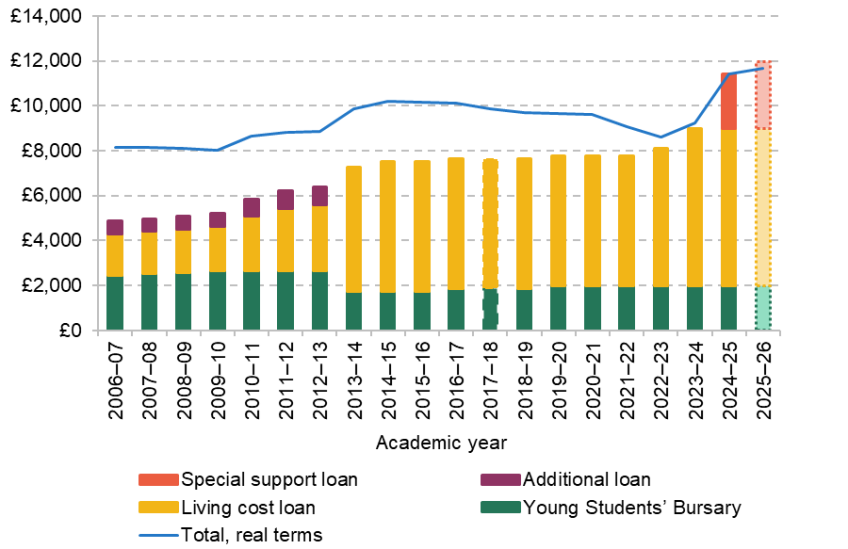

Another major change to higher education funding this academic year was a substantial increase in living cost support for Scottish students. As we discussed more fully in February, Scottish undergraduates are also entitled to support with their living costs, predominantly in the form of income-contingent student loans, with some non-repayable grants for those from low-income households. This support had become substantially less generous over time, but a £900 increase in loan entitlements in 2023–24 represented the first real-terms increase in support for those from the lowest-income households since 2014–15.

From this academic year, there was another substantial increase in up-front support with the introduction of a special support loan of £2,400 available to all Scottish full-time undergraduates and postgraduates.8 As shown in Figure 5, this has taken the maximum living cost support for a Young Student from £9,000 to £11,400. This represents an increase since last year of £2,183 in today’s prices – a 23.7% real-terms increase for the poorest (and proportionately larger for those from better-off households).Real-terms living cost support for the poorest students will be the highest this academic year that it has been since the SNP first entered the Scottish Government in 2007. It remains to be seen what take-up of this new loan entitlement will be, but it is likely to have helped many students to meet their living costs and perhaps allowed some to do fewer hours of paid part-time work alongside their studies.

Figure 5. Entitlements to living cost support for Scottish Young Students with low household income, by academic year

Note: Entitlements for Scotland-domiciled full-time undergraduates, classed as Young Students and with the lowest assessed household income. Real-terms figures based on CPI in quarter 1 of the relevant academic year. 2025–26 figures assume cash freezes in the Young Students’ Bursary and living cost loan, and an increase in the special support loan such that total support keeps up with changes in the Living Wage.

Source: SAAS funding guides (various years; historical years accessed from https://www.gov.scot/publications/foi-19-01376/); ONS CPI Index (mm23) and forecast CPI from OBR EFO, October 2024.

The Scottish Government is expected to announce its plans for 2025–26 in the coming months. The changes this year delivered on a Programme for Government commitment to increase the student support package to the ‘equivalent of the Living Wage’, based on a student working 950 hours per academic year at the real living wage of £12 an hour produced by the Living Wage Foundation. The relevant wage rate was increased to £12.60 in October. If the Scottish Government wants to keep up with this, the maximum support package would need to increase by a further 5% in cash terms next academic year, to £11,970. Achieving this through the special support loan would require it to rise by £570, and would constitute another real-terms rise in living cost support of 2.5% for the poorest.

Importantly, the issue of student loans to Scottish students and the eventual costs of any loan write-offs are met by the UK government (with the UK government also keeping the loan repayments). This means that increases in the generosity of living cost support which come through loans come at no cost to the Scottish Government’s main budget, so long as this funding arrangement continues.

A higher education headache

While the financial position of Scottish universities was relatively healthy in 2022–23, at least compared with their English counterparts, the continuing decline in funding for domestic students is likely to have contributed to a squeeze since. Likely falls in international student fee income – in particular from those studying for postgraduate degrees – and higher staff costs as a result of higher employer National Insurance contributions present major risks this academic year, and the potential increase in fees charged to rUK students from 2025–26 will do little to offset these challenging headwinds. The sector will be looking to see whether improvements in the Scottish Government’s fiscal position translate into more funding for higher education at the upcoming Budget, or whether universities are again asked to do more for less.