Education is a ‘devolved matter’ in the UK, and there has been growing divergence in education policies among the four parts of the UK since 1999. The Scottish Government has made starkly different policy decisions on how higher education should be funded, and how the costs should be shared between graduates and taxpayers, in part reflecting different priorities and objectives. Indeed, higher education is one area where Scotland’s public service provision has long appeared more generous than that in England, with students who choose to stay in Scotland for university not required to pay any tuition fees. Instead, the costs of their teaching are all met by the Scottish Government, at a cost of around £900 million each year. In addition, Scotland still provides the poorest students with non-repayable bursaries of up to £2,000 per year towards their living costs, alongside income-contingent loans of at least £6,000 per year.

Recently announced changes will see the system become more generous for students and graduates next year. First, students will be eligible for larger living costs loans, delivering on a 2021 commitment to provide a total package of student support ‘the equivalent of the Living Wage’ by 2024–25. Second, the loan repayment threshold (above which graduates make repayments on their loans) will increase from £27,660 to £31,395 in April 2024, reducing monthly repayments for many graduates. Importantly, under current funding arrangements, the UK government provides up-front funding for loans issued to Scottish students, and ring-fenced funding for any eventual loan write-offs. This means increases in generosity through the loan system do not impact the amount the Scottish Government has to spend on competing policy priorities, as determined at the Scottish Budget each year.

But under the current system of free tuition, the Scottish Government does cover the full costs of teaching for Scottish undergraduates who study in Scotland. The Scottish Government controls these tuition costs in two ways: through control of per-student funding and by restricting the number of funded places. Per-student funding has been gradually eroded over the last decade, with further funding cuts announced in the 2024–25 Budget, implying cuts to the number of funded places.

In this chapter of our second annual Scottish Budget Report, we explain how higher education is funded for Scottish students who stay in Scotland to study. We consider issues related to living cost support (for which the Scottish Government has provided much additional support in the Budget) and issues around funding for teaching that remain unresolved. We draw on new modelling of student loan repayments to examine the distributional consequences of the current funding model, and to consider potential policy options in light of the pressures on the Scottish Budget highlighted in Chapter 3.1

Key findings

1. The Scottish Government spends around £900 million each year on teaching Scottish undergraduates, through the main teaching grant and a notional tuition fee which is paid on behalf of Scottish students who stay in Scotland for their studies. Unlike in the rest of the UK (where students are charged tuition fees), the Scottish Government meets the whole costs of teaching, and has controlled these costs in recent years by controlling the number of places for Scottish students and freezing per-student resources. Funding per student per year of study has fallen by 19% in real terms since 2013–14 and, as a result, Scottish universities are increasingly reliant on international student fees.

2. A cut to higher education resource funding (the budget line that includes the main teaching grant) was announced at the Scottish Budget for 2024–25. This is a cash-terms cut of 6.0% compared with initial planned spending in 2023–24, or of 3.6% year-on-year accounting for in-year savings that had already been made this year since the 2023–24 budget was initially set out. This implies that funding for home students will fall, with the Scottish Funding Council (which allocates funding to universities) trading off a further squeeze on per-student resources with potential cuts to the number of funded places.

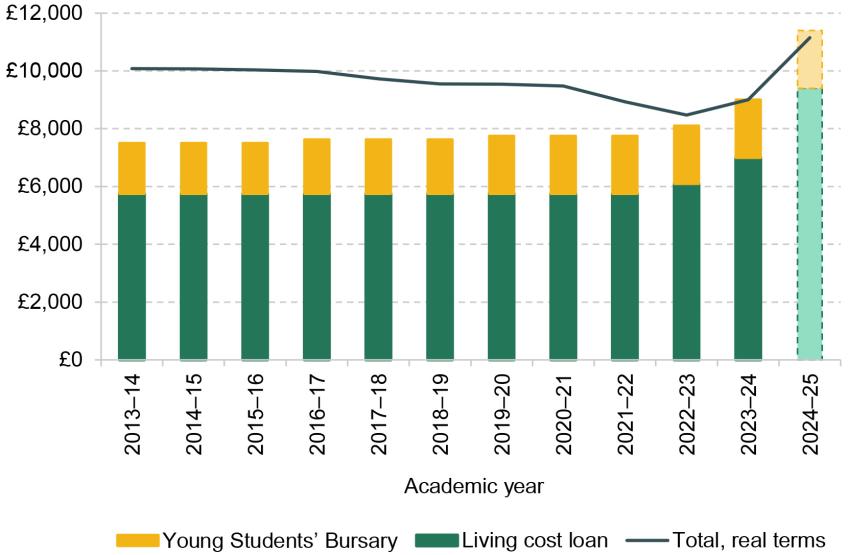

3. Around £600 million is provided in the form of living cost support to students each year, the vast majority in the form of living cost loans (£500 million), alongside non-repayable bursaries of up to £2,000 per year for the poorest students. Living cost support has become less generous over time, with total support for the poorest students declining in real terms by 16% (£1,600 per year) between 2013–14 and 2022–23, and further implicit cuts due to the freezing of the household income thresholds that determine entitlements.

4. A £900 cash increase in loan entitlements this academic year, in response to cost of living pressures, was the first real-terms increase in support since at least 2013–14. A much bigger increase of £2,400 per year is planned for next academic year. This delivers the Scottish Government’s commitment to provide a total package of student support ‘the equivalent of the Living Wage’ by 2024–25. The earnings threshold above which Scottish borrowers make student loan repayments is also set to increase in April 2024, from £27,660 to £31,395. If there was full take-up of living cost support, these changes would increase average lifetime loan repayments in real terms by around £5,000, and increase average loan write-offs by around £3,400 per student.

5. Importantly, the costs of issuing loans to Scottish students, and of any eventual loan write-offs, are currently met by the UK government. Increases in generosity of support or in repayment terms for Scottish borrowers of the type planned for 2024–25 come at no cost to the Scottish Government’s main budget so long as this funding arrangement continues.

6. Given the system applying in 2024 (and assuming full take-up of living cost support) and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s assumptions about inflation and earnings growth, we expect around two-thirds of Scottish borrowers to repay their loans in full. The highest-earning half of graduates will repay approximately what they borrowed in real terms (£34,000), with much lower average lifetime repayments (£4,900) amongst the lowest tenth of graduates by lifetime earnings.

7. This system costs the Scottish Government around £850 million more per cohort (£28,700 more per student) than the English system would. From this spending, Scottish graduates on average gain £23,800 (largely through lower borrowing and loan repayments), and the UK taxpayer gains £4,900 per student in the form of lower loan write-offs.

8. Under the current ‘free tuition’ system, increased teaching resources for home undergraduates can come only through additional cash expenditure from the Scottish Government. Requiring some contribution from students towards the costs of their tuition could deliver a significant boost to teaching resources, or ease pressure on the Scottish budget. But this would increase lifetime contributions from Scottish graduates or mean much higher loan write-offs, potentially risking the arrangement under which the cost of these write-offs is met by the UK government.

5.1 How is Scottish higher education funded?

In this section, we describe how higher education in Scotland is funded currently, focusing on the vast majority of undergraduate students who stay in Scotland to study2 . We examine recent trends in funding for teaching and living cost support, changes planned for the 2024–25 academic year, and how this spending affects the Scottish Government’s main budget.

Teaching costs

The most striking feature of how higher education is funded in Scotland is the absence of tuition fees for most Scottish students. For those who choose to stay in Scotland for their studies, the full costs of undergraduate teaching are met by the Scottish Government.

Technically, Scottish universities charge ‘home fee’ students a tuition fee of £1,820 per year. However, the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS), an executive agency of the Scottish Government, pays these tuition fees on behalf of most Scottish undergraduate students working towards their first degree. In 2022–23, SAAS paid tuition fees for 117,000 full-time undergraduate students, at a total cost of £200 million. In addition, the Scottish Government also provides funding to the Scottish Funding Council, which distributes this to universities (much as the Office for Students does in England). The main teaching grant was worth £700 million (or just under £5,800 per student) in both 2022–23 and 2023–24.

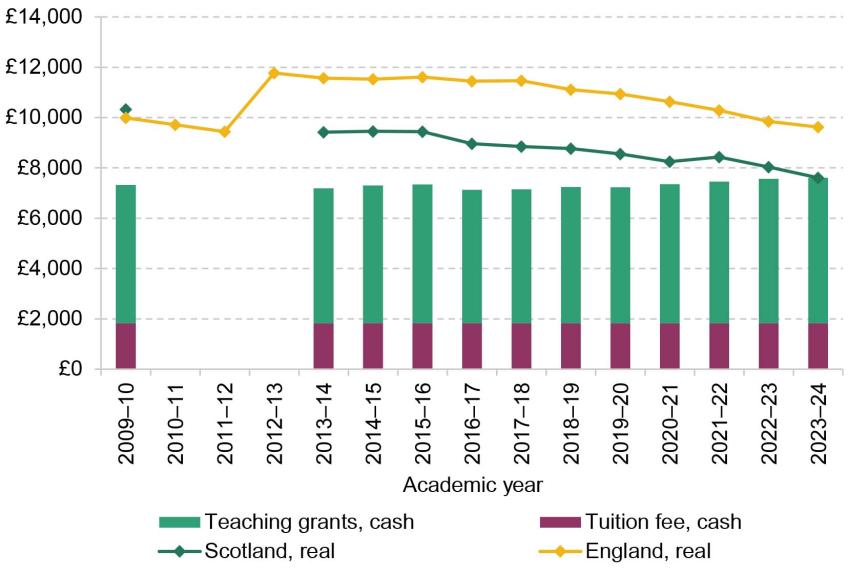

Together, Scottish universities received direct public funding of around £900 million for teaching home undergraduate students in academic year 2023–24, or £7,610 per student. Figure 5.1 shows that this was around 19% less in real terms per student than in 2013–14, as the tuition fee has been fixed in cash terms at £1,820 since 2009–10 and the main teaching grant per student has risen by less than inflation.

Figure 5.1. Up-front per-student resources for teaching per year

Note: Tuition fee for ‘home fee’ full-time first degree student from SAAS, plus main teaching grant divided by the number of ‘funded’ places. Data not available for years 2010–11 to 2012–13. Real-terms figures based on financial year GDP deflator. Figures for England reflect Office for Students grants, the tuition fee cap and estimated bursaries and fee waivers funded by English universities (which reduce resources available for teaching).

Source: Scottish Funding Council’s university final funding allocations (various years); Drayton et al. (2023); https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-november-2023-autumn-statement.

This is also around £2,020 (21%) lower than the per-year resources available for an English university teaching an England-domiciled undergraduate in 2023–243 . Annual resources for undergraduate teaching were similar north and south of the border in 2009–10, before the increase in tuition fees charged by English universities from 2012–13 injected additional funding. Since then, the trends – a gradual erosion of resources, with fees frozen and below-inflation increases in grants – have been similar.

Importantly, the Scottish Funding Council allocates each university a number of ‘funded places’ for eligible Scottish students, which attract funding from the main teaching grant. Universities are able to recruit up to 10% above this number, receiving only around a quarter of the average per-student funding for them, and then face financial penalties for recruitment beyond this4 . This restricts the number of Scotland-domiciled students Scottish universities can recruit, controlling the costs of teaching for the Scottish Government – which is especially important given all of these costs are met by the government, rather than through loans. No such caps exist in England or Wales.

In contrast, universities in Scotland can charge students from the rest of the UK (rUK) tuition fees of up to £9,250 per year, and international students much more, and face no caps on numbers5 . At the margin, a Scottish university receives much more funding for teaching an additional rUK or international student than an additional Scottish student. This means Scottish universities have a financial incentive to expand provision, but not for Scottish students6 .

As per-student resources for teaching home students have been eroded over time, international student fees have become increasingly important for the finances of many Scottish universities. Fees for teaching students from outside Scotland were worth around £1,413 million to Scottish universities in the 2021–22 academic year, accounting for around 30% of their total income7 .

The ability of Scottish universities to attract international students has so far allowed their fees to cross-subsidise the teaching of home undergraduates. This has also been the case at many English universities, such that the UK government now faces an acute trade-off between funding for English universities and reducing headline net migration figures (Emmerson et al., 2024)8 . The sustainability of the university funding model in Scotland also depends partly on the UK’s immigration policy, over which the Scottish Government does not have control.

Planned changes in 2024–25

The tuition fee for home fee students is expected to remain at £1,820 in 2024–25 (a slight real-terms cut). The size of the main teaching grant and the number of funded places are yet to be confirmed. However, the main teaching grant sits within the Scottish Government’s ‘HE Resource’ budget, and movements in this budget line provide a good indication of what might happen to teaching funding next academic year9 .

Planned HE Resource spending at the 2023–24 Budget was £809 million for the 2023–24 fiscal year, £20 million more in cash terms than the budget for 2022–23 (Scottish Government, 2023a). However, the 2023–24 spending plans have been reduced since they were first set; in May 2023, the Scottish Funding Council confirmed that this extra £20 million had been identified as a necessary in-year saving by the Scottish Government and would not be distributed to universities10 . This leaves planned HE Resource spending in 2023–24 at £789 million.

Figures in the Scottish Budget 2024–25 show the budget for HE Resource falling further to £761 million in 2024–25. This is a cash-terms fall of 6.0% compared with the original budget for 2023–24, or (as is a better indicator of the change in resources from one year to the next) of 3.6% year-to-year accounting for in-year cuts.

A further squeeze on real-terms per-student funding is likely, and the supporting documents to the 2024–25 Budget mention reductions in first-year university places. Exactly how the planned savings will be shared between these two – reductions in funding per place and in the number of places – will be confirmed in university funding allocations, with indicative allocations typically published in April.

Living cost support

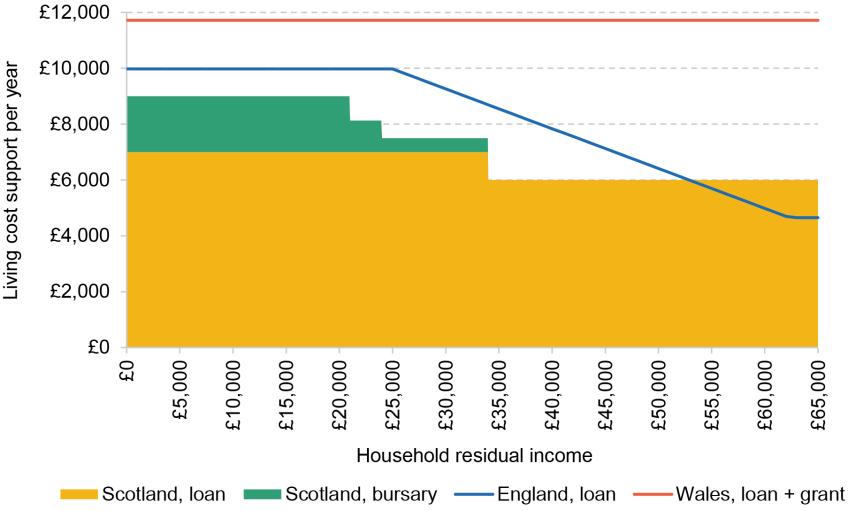

Students can also access financial support towards their living costs while they study – through a combination of loans and non-repayable bursaries from SAAS11 . In 2023–24, those classed as Young Students (broadly someone under the age of 25 who has not supported themselves financially for three years, is not married and does not have dependent children) are entitled to borrow either £6,000 or £7,000 per year of study. Those with low household incomes (typically parental incomes) are also entitled to non-repayable bursaries of between £500 and £2,000 per year.

As shown in Figure 5.2, total support available varies from £6,000 (for anyone with household income over £34,000) to £9,000 per year. Support varies discontinuously based on household income; there are sudden changes in entitlements at specific income thresholds. Someone with a household income of just over £34,000 would receive £1,500 less support per year than someone with a household income of just under £34,000. This creates unfairness and reduces work incentives for those with incomes close to these arbitrary thresholds which, if understood by households, could induce some to reduce their earnings.

Figure 5.2. Entitlements to living cost support by household income, academic year 2023–24

Note: Entitlements for Young Students in Scotland, and for England- and Wales-domiciled students living away from home and not attending a London university.

Source: https://www.saas.gov.uk/full-time/undergraduates/student-loan-bursary-tuition-fees; Bolton, 2024.

Unlike in England and Wales, where a student living away from home receives more funding, and studying in London even more, entitlements for Scottish students do not depend explicitly on where a student lives. Instead, they depend on whether someone is classed as a Young Student (as described above) or an Independent Student. Those in the latter group are typically eligible for the same total level of living cost support, but a greater share of this is provided as loan rather than grant12 .

The total amount of support available to an equivalent student also varies substantially in different parts of the UK, as shown in Figure 5.2. Many Scottish students in 2023–24 are entitled to less total support than an equivalent English student, although a small portion of the Scottish support would be provided in the form of a grant for some. In Wales, student support is significantly more generous, with all students entitled to total support of £11,720 in 2023–24, and every student entitled to a non-repayable grant of at least £1,000, increasing to £8,100 for the poorest.

A range of other funding is available to Scottish students based on their personal circumstances. For instance, there are grants available for students who have a disability, are carers or are lone parents. Students who are under 25 and permanently estranged from their parents are entitled to an Estranged Students’ Bursary of £1,000 and a living cost loan of up to £8,000. Any student who has ever been looked after by a local authority before the age of 18 is eligible for a Care Experienced Students’ Bursary of £9,000, instead of a living cost loan or other bursary.

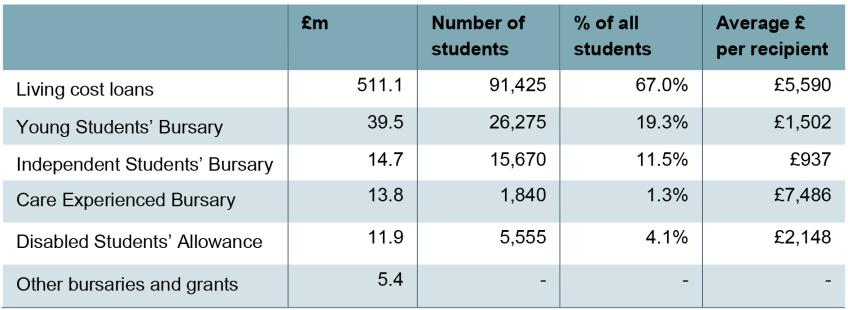

As shown in Table 5.1, £511 million of living cost loans were issued to full-time students by SAAS in 2022–23, along with bursaries and grants totalling £85 million. Around two-thirds of students receiving some support from SAAS in 2022–23 (including having tuition fees paid on their behalf) received some living cost loan that academic year. This implies much lower take-up of living cost loans than the take-up of maintenance loans in either England (91%) or Wales (94%), and contributes to lower loan borrowing amongst Scottish students (something we return to in Section 5.2)13 .

Table 5.1. Living cost support provided to full-time students by SAAS in 2022–23

Note: ‘% of all students’ is as a share of all full-time students receiving any support from SAAS, including tuition fees and fee loans. Includes support provided to postgraduate students, EU-domiciled students and Scotland-domiciled undergraduates studying in the rest of the UK. ‘Other bursaries and grants’ includes Dependants’ Grant, Lone Parents’ Grant, Educational Psychology Grant and adhoc payments.

Source: SAAS ‘Higher education student support in Scotland 2022–23’, tables FT.1 and FT.3, available at https://www.saas.gov.uk/about-saas/statistics/stats-22-23.

The system of living cost support for Scottish students has become substantially less generous over time. This is for two reasons. First, the cash value of support has increased little until recently. From 2013–14 until 2021–22, the total living cost support a Young Student with a low household income was eligible for increased from £7,500 to £7,750. By 2022–23, support was worth 16% less in real terms than in 2013–14, a cut of around £1,600 in current (2024 Q1 CPI real) prices, as shown in Figure 5.3. Indeed, a £900 increase this year in the maximum amount all Scottish students can borrow, in response to cost of living pressures, was the first real-terms increase in support since at least 2013–1414 .

Figure 5.3. Entitlements to living cost support for Scottish Young Students with low household income, by academic year

Note: Entitlements for Scotland-domiciled full-time undergraduates, classed as Young Students and with the lowest assessed household income. Real-terms figures based on CPI in Q1 of the relevant academic year.

Source: https://www.saas.gov.uk/about-saas/stats-2022-23/policy-background; https://www.saas.gov.uk/full-time/undergraduates.

As highlighted by Ogden and Phillips (2023), there have also been freezes to the parental earnings thresholds that determine entitlements. Since 2016–17, the lowest parental earnings threshold has increased from £19,000 to £21,000, but the next two thresholds have been frozen in cash terms, despite growth in average earnings of 29% over the same period. This means that some students are eligible for a quarter (£2,120) less in real terms in 2023–24 than a student whose family was in the same position in the earnings distribution would have been entitled to in 2016–17.

Planned changes in 2024–25

The amount of living cost support for students is set to increase significantly next academic year. In December, the Scottish Government announced that all Scottish students will see their loan entitlement increase by £2,400 in Autumn 2024, taking the maximum living cost support for Young Students from £9,000 to £11,40015 . This delivers on a commitment in the Programme for Government 2021 to provide a total package of student support ‘the equivalent of the Living Wage’ by 2024–25 (Scottish Government, 2021)16 .

Importantly, this calculation has been based on the real living wage of £12 an hour produced by the Living Wage Foundation, which is higher than the National Living Wage (which will rise to £11.44 an hour from April 2024). Accounting for inflation, this represents a real-terms increase of £2,150 (24%) for the poorest, and will restore the real-terms generosity of the 2016–17 system for most. It will bring entitlements for Scottish students with household incomes between around £20,000 and £40,000 roughly in line with their English counterparts, and will be much more generous than the English system for those from the poorest and the richest households.

However, the income thresholds that determine eligibility will be frozen in cash terms for another year. Given forecast nominal earnings growth of around 3% in 2024–25, some students may still see their living cost entitlements fall year-on-year as their household income just surpasses a specific threshold for support, even if they have become no better off in relative terms.

How much is spent overall, and how does this appear in the Scottish Government’s budget?

In 2022–23, around £1.5 billion was spent in total on undergraduate higher education – including teaching and living cost support. Of this, cash expenditure on student support through SAAS (tuition fees paid on behalf of Scottish students, and bursaries) and direct grants provided to universities through the Scottish Funding Council amounted to around £1 billion. This expenditure appeared in the Scottish Government’s main budget as departmental expenditure limit (DEL), coming from Scottish Government ‘Fiscal Resource’, and was explicitly traded off by the Scottish Government against spending on competing policy priorities. In contrast, loans provided to Scottish students – for living costs, and for tuition fees for the minority who studied outside Scotland – were treated as a UK government annually managed expenditure (AME) programme, and so financed by the UK government. Any eventual loan write-offs (or impairment costs) are met through separate ring-fenced funding from HM Treasury (HMT)17 . Around £0.5 billion of loans were issued to Scottish students, and this spending was not subject to the same budget limits.

Of course, the long-run cost to the UK government of providing these loans will be lower than this initial loan outlay as graduates make repayments towards their loans. This funding arrangement – the loan outlay and eventual write-offs being funded by HMT – depends on the Scottish Government higher education funding policy being broadly similar, or having ‘broadly comparable’ costs to the UK government’s policy. We provide estimates of this long-run cost in Section 5.2, and consider one measure of ‘broadly comparable’ costs in Section 5.3.

As highlighted earlier, the Scottish Budget suggests that spending on teaching will fall in 2024–25. Without substantial increases in bursaries and grants – which are not expected – spending on higher education from Scottish Government Fiscal Resource is likely to fall year-on-year. At the same time, increases in entitlements to living cost loans are likely to increase loan outlay, increasing UK-funded AME spending.

5.2 How do Scottish students repay their loans?

Students are liable to start repaying their loans from the April after they finish their course. For employees, student loan repayments are deducted automatically from their earnings by their employer through PAYE. How much graduates repay depends on their earnings: graduates make no repayments if they earn below a certain threshold (currently £27,660) and repay 9% of their earnings above that threshold. Any outstanding loan is written off at the end of the repayment period (currently 30 years) with no adverse consequences for graduates.

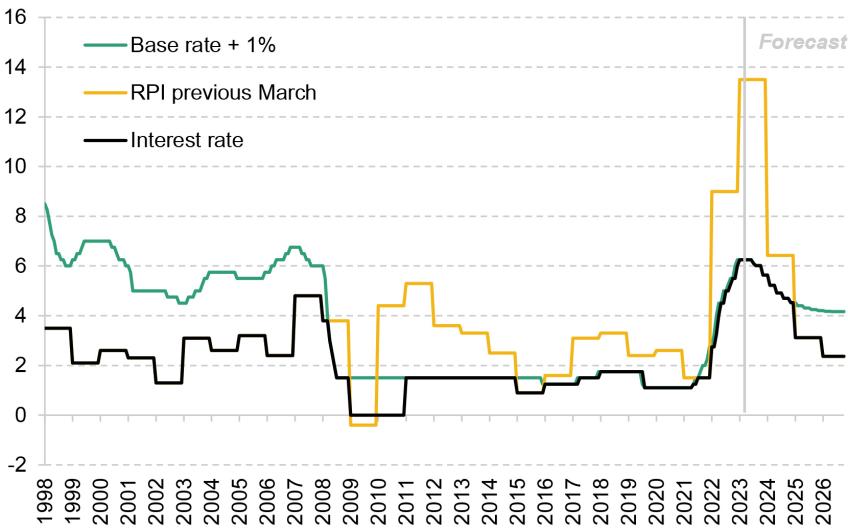

These loans accrue interest, during study and after graduation, at the same rate. This rate typically changes each September, and is set to be the lower of two things: the Bank of England (BoE) base rate plus 1%, and retail price inflation (RPI) in the year to the previous March. The policy intention behind this is to ensure rates remain low – and this has largely been delivered over the recent period of very low interest rates, with the interest rate remaining below 2% from 2009 until September 2022, as shown in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4. Interest rate charged on Plan 4 student loans

Note: Figures from February 2024 onwards are forecasts.

Source: DfE guidance (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/how-interest-is-calculated-plan-4); Office for Budget Responsibility (2023); ONS RPI All Items (https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/czbh/mm23); Bank of England base rate history (https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/boeapps/database/Bank-Rate.asp); conditioning assumptions from Bank of England (2024).

The interest rate has since risen steadily as the Bank of England successively increased the base rate in response to high inflation, and is currently 6.25% (the base rate of 5.25% plus 1 percentage point). Based on market expectations of the path for the base rate, the interest rate in Scotland is expected to fall gradually over the next 18 months, and then to fall more sharply to 3.1% in September 2025 and to 2.4% in September 2026. While the period of high interest rates for Scottish borrowers will be relatively short-lived, the use of a lagged measure of inflation means it will persist beyond the period of high inflation itself, and this is likely to increase political pressure on the Scottish Government to reduce interest rates18 .

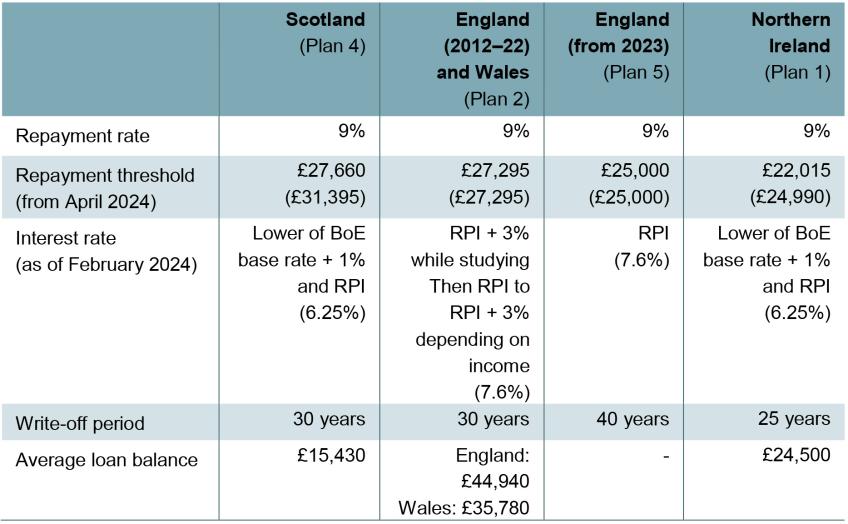

In broad terms, the loan repayment terms for Scottish borrowers are similar to those for borrowers in other parts of the UK, as shown in Table 5.2. The same interest rate calculation method applies for borrowers in Northern Ireland, although they face a lower repayment threshold and a shorter write-off period. The terms for Scottish borrowers are definitely more generous than the new Plan 5 loan terms, which apply to England-domiciled students who start courses from 2023 onwards. In particular, Scottish borrowers can earn more before making repayments and make lower monthly repayments, repay for fewer years before their loans are written off, and face an interest rate that is the same (RPI) or lower.

Table 5.2. Student loan repayment terms across the UK

Note: Loan balances on entering repayment are as of 2022–23 financial year, and are averages amongst all borrowers on entry into repayment by government administration that funded the loan. The interest rate applied to Plan 2 loans typically varies with graduates’ incomes, but is currently subject to a cap at the Prevailing Market Rate such that the same interest rate applies to all loans.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/repaying-your-student-loan; https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-comparisons-to-financial-year-2023/uk-comparisons-to-financial-year-2023.

The biggest difference between parts of the UK is in the average loan balances of home students funded by different government administrations. Those from Scotland have by far the lowest average loan balances on entry into repayment at £15,430, compared with £24,500 in Northern Ireland, £44,940 in England (where around 95% of students take out loans for tuition fees) and £35,780 in Wales (which has the same higher tuition fee cap as England, but provides more living cost support through grants rather than loans). The much lower borrowing of Scottish students is despite typically longer courses, and reflects three main factors: the absence of tuition fees (and so tuition fee loans) for most Scottish students, lower entitlements to living cost loans for many, and lower take-up of living cost loans amongst eligible Scottish students.

Indeed, a typical Scottish student on a four-year course at a Scottish university who took out all the living cost loan they were entitled to might expect to graduate with a loan balance of between £24,000 and £28,000 based on entitlements in 2023–24. Given the planned increase in loan entitlements (and even with no further increases), someone starting a course next academic year could instead expect to borrow between £34,000 and £37,600 over four years.

How much can Scottish students expect to repay?

The income-contingent nature of student loan repayments means future repayments depend on the future earnings of Scotland’s graduates. Forecasting future earnings is a hugely uncertain exercise, reflecting forecasts for average wage growth over the next 35 years, as well as how this is distributed across individuals over the course of their careers, and other changes for individuals (such as changes in hours or periods of unemployment).

The IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator19 models the lifetime repayments of a single cohort of Scottish full-time undergraduate students, focusing on those who studied at a university in Scotland20 . The model makes some key simplifying assumptions: that all undergraduates start courses at age 18 and study for the intended course length; that all students are eligible for living cost support as if they were Young Students or Care Experienced Students, and take up all the support they are entitled to; that borrowers do not make voluntary contributions; and the parameters of the student loans system do not affect graduates’ gross earnings.

Under these assumptions, and policies in place in 2023–24, we estimate that students starting in 2023 could expect to borrow £25,900 on average over their courses, and to repay £22,300 on average over their lifetimes, adjusted for inflation21 . Around three-quarters of students would fully repay their loans, with those having some debt written off after 30 years concentrated in the bottom three deciles of lifetime earnings22 .

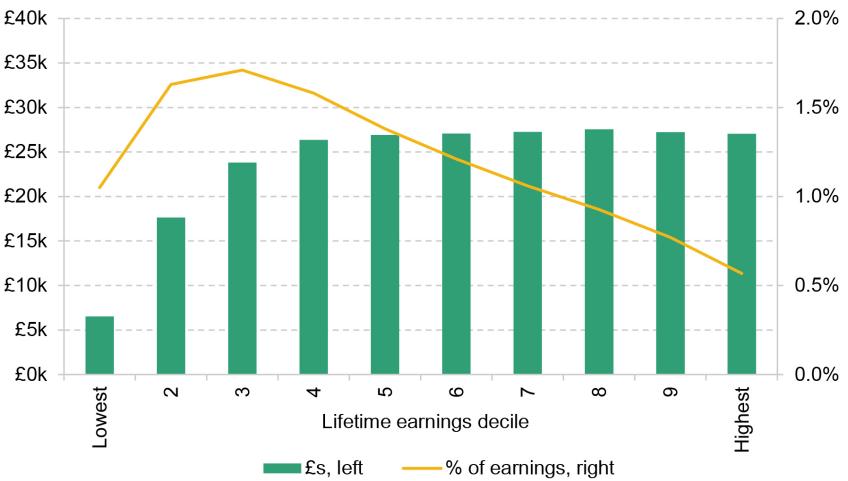

As shown in Figure 5.5, borrowers in the top six deciles of lifetime earnings are expected to repay around £27,000 on average (very slightly more than they borrowed once adjusted for inflation), with those in the lowest decile repaying only £6,500 on average. As a share of lifetime earnings, repayments are highest in the third decile (1.7% on average) and fall to around 0.6% amongst the highest tenth of earners23 .

Figure 5.5. Lifetime loan repayments, £s and as a percentage of lifetime earnings, by lifetime earnings decile

Note: Expected lifetime repayments for a single cohort under the system applying for the 2023 entry cohort. Repayments and earnings are in undiscounted CPI real terms (2023 prices).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

The share of graduates making any repayments in a year reaches 40% at age 25, peaks at around 70% at age 31, and then declines steadily until only around 20% are still making repayments in the year before any remaining balance is wiped. As shown in Figure 5.6, amongst those in the top third of graduates by lifetime earnings, average repayments peak at £2,000 a year at age 31 – around 4.5% of their earnings in that year – before falling during their 30s as some people have repaid in full and therefore cease making repayments. Amongst the middle tercile, average repayments peak later, at around £1,500 per year in their mid 30s, but many more repay throughout their 30s and early 40s. For the lowest third of lifetime earners, average repayments are much lower until their early 50s.

Figure 5.6. Average annual loan repayments, by age and tercile of lifetime earnings

Note: Smoothed (three-year rolling averages) average annual loan repayments amongst individuals in different terciles of the lifetime earnings distribution, at each age, assuming all students begin courses at age 18. Real-terms figures based on financial year CPI.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

Who bears the costs of HE in the long run?

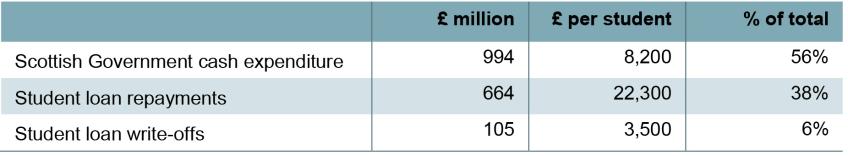

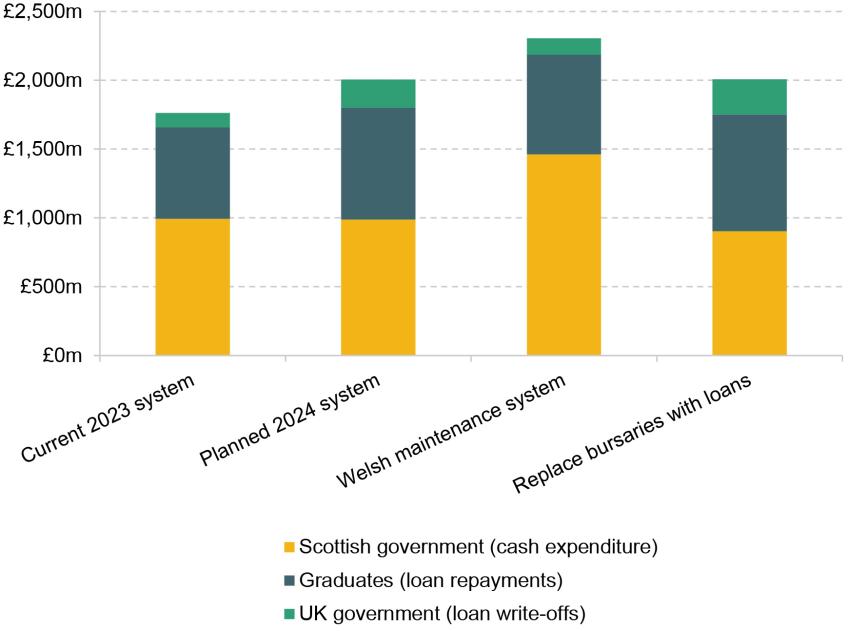

Under the assumptions described above, and assuming that policy remains as it was in 2023, we estimate the long-run costs of higher education for the cohort of Scottish undergraduates starting courses in 2023 at Scottish universities would be £1,763 million, adjusted for inflation. This would be split as described in Table 5.3. Of the total cost of undergraduate teaching and associated grant- and loan-funded living costs for a single cohort of students, around 56% of the long-run cost would be met by the Scottish Government, 38% by graduates themselves and 6% by the UK government.

Table 5.3. Long-run costs of higher education for the 2023 cohort, under 2023 policy

Note: All figures are undiscounted, RPI real, in 2023 prices. Assumes full take-up of living cost support. Scottish government cash expenditure includes main teaching grant (£0.7 billion), tuition fees paid on behalf of Scottish students (£0.2 billion) and bursaries towards living costs (£0.1 billion).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

One measure of the long-run cost of student loans is the resource accounting and budgeting (RAB) charge, an estimate of the long-run cost of loans issued in the current year, based on future loan write-offs and interest subsidies. Our preferred approach is to estimate the proportion of loan outlay issued each year that is not expected to be repaid, discounting future repayments only to account for inflation. With no real discounting (i.e. with no discounting in addition to adjusting for inflation), we estimate the RAB charge for the 2023 Scotland cohort at +14%, suggesting a cost of around £3,500 on average per student. Intuitively, total student loan write-offs (£105 million) are 14% of the total value of loan write-offs plus loan repayments (£769 million), when both are valued in RPI real 2023 prices.

An alternative measure of the RAB charge used by the UK government instead values future repayments in present terms using the HMT discount rate. This assumed discount rate is meant to capture the opportunity cost of government funds – the cost of funding student loans rather than undertaking other government projects. However, the Treasury uses a negative real discount rate which, counterintuitively, means the same repayment in real terms now counts for more in the RAB charge calculation the further in the future it is made24 . Under the current system, we estimate the RAB charge for the 2023 Scotland cohort using the UK government preferred discount rate to be minus 11% (suggesting the UK government makes around £2,800 on average per student)25 .

Planned changes in 2024–25

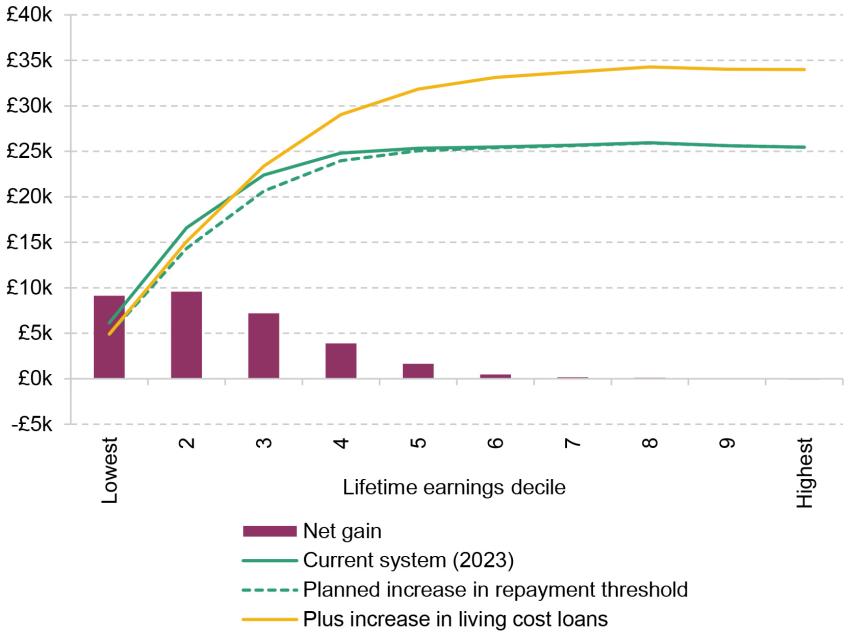

As described above, several changes are planned for 2024–25 which will affect the cost of the system. The repayment threshold is set to increase to £31,395 from April 2024. This alone would increase the RAB charge slightly from +14% to +16% (with no real discounting). As shown in Figure 5.7, those in the bottom four deciles of lifetime earnings could expect to repay around £1,500 less over their lifetimes as a result, whereas those in the top half of the income distribution could expect to repay roughly the same over their lifetimes (with lower monthly repayments but made for more years).

Figure 5.7. Lifetime loan repayments under different policies, £s, by lifetime earnings decile

Note: Expected lifetime repayments for a single cohort. ‘Net gain’ measures the increase in up-front living cost support, less the increase in lifetime loan repayments. All figures are in undiscounted RPI real terms (2023 prices). Planned increase in repayment threshold models impact of changing repayment threshold in 2023 to £30,261 (equivalent to £31,395 in 2024 given expected earnings growth). Assumes full take-up of living cost loans under all policies.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

Amongst those taking up the full living cost support they are entitled to, the planned £2,400 increase in living cost loan entitlements will increase total living cost support per student by around 28% (from £29,500 to £37,70026 ), and will also increase both lifetime student loan repayments and write-offs. On average from these two changes, the top half of graduate lifetime earners can expect to repay any additional borrowing in full, although they may still benefit from the ability to borrow more at a time when they are especially likely to be credit-constrained. Those in the bottom half of the income distribution gain more in additional living cost support than the increase in their lifetime loan repayments, as shown in Figure 5.7, with those in the poorest tenth around £9,100 better off on average under the 2024 system.

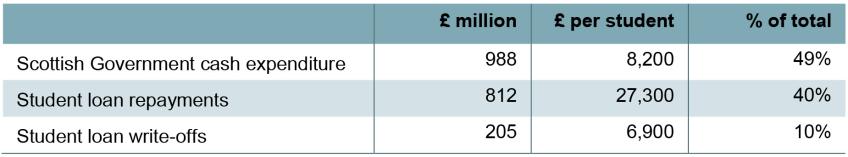

Together, these two changes planned for 2024–25 will increase the total government outlay on higher education from £1.8 billion to around £2 billion per cohort. The Scottish Government will meet around half of the long-run costs under the new policy, with an increasing share of costs falling on graduates in the long run (40%) and a near-doubling in the cost of eventual loan write-offs to the UK government (see Table 5.4). We estimate that the RAB charge under 2024 policy will be +20% (with no real discounting).

Table 5.4. Long-run costs of higher education for the 2023 cohort, under 2024 policy

Note: See note and source to Table 5.3.

The increased generosity of the living cost support system for Scottish students and the improvement of loan terms for Scottish graduates will be shared between Scottish graduates and the UK government, rather than being a burden on the Scottish Government’s main budget. If students took up their full entitlements to living cost support, these changes would substantially increase average lifetime loan repayments amongst Scottish graduates (by around £5,000) and would add around £100 million (£3,400 per student) to the cost of loan write-offs to the UK government.

5.3 What could a different funding system look like?

Ogden and Phillips (2023) identified two main challenges facing the Scottish model for higher education funding in the run-up to the 2024–25 Budget: a decline in the generosity of living cost support and real-terms cuts in teaching resources. The first has been at least partially addressed. As already highlighted, the Scottish Government plans to make changes that from 2024–25 will increase the generosity of up-front support for Scottish students and reduce the monthly repayments of graduates. That these changes will only affect loan entitlements and expected repayments means they will be without cost to the Scottish Government’s main budget. But further cuts to university funding are planned, and as discussed in Chapter 3, while the Scottish budget situation is better than expected a year ago, it remains very challenging.

In this section, we use the IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator to examine the costs and distributional consequences of some further alternative funding models, taking the planned 2024–25 system as the baseline and highlighting the trade-offs between competing objectives.

The Scottish Government could be minded to go further on the generosity of living cost support for students. One potential option would be adopting the maintenance system for Welsh students. This would increase living cost support per student by a further 27% compared with 2024–25 plans. However, much of the additional cost would be in the form of bursaries, at a cost of £473 million to the Scottish Government’s main budget. This is unlikely to be an appealing option given budgetary challenges.

Alternatively, the Scottish Government could retain the level of generosity planned from Autumn 2024, but with less impact on the Scottish budget, by providing support through loans rather than bursaries. Replacing the Young Students’ Bursary with additional living cost loans would leave total living cost support unchanged, while replacing around £85 million of Scottish Government expenditure with additional loans. Graduates would repay just under half of the additional loan outlay (about £38 million), with the UK government meeting the cost of additional loan write-offs (about £48 million), as shown in Figure 5.8.

Figure 5.8. Long-run cost of higher education borne by different parties, under different policies

Note: Assumes full take-up of living cost loans and bursaries. Cash expenditure falls slightly under planned 2024 system given assumed cash freezes to bursaries and teaching resources.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

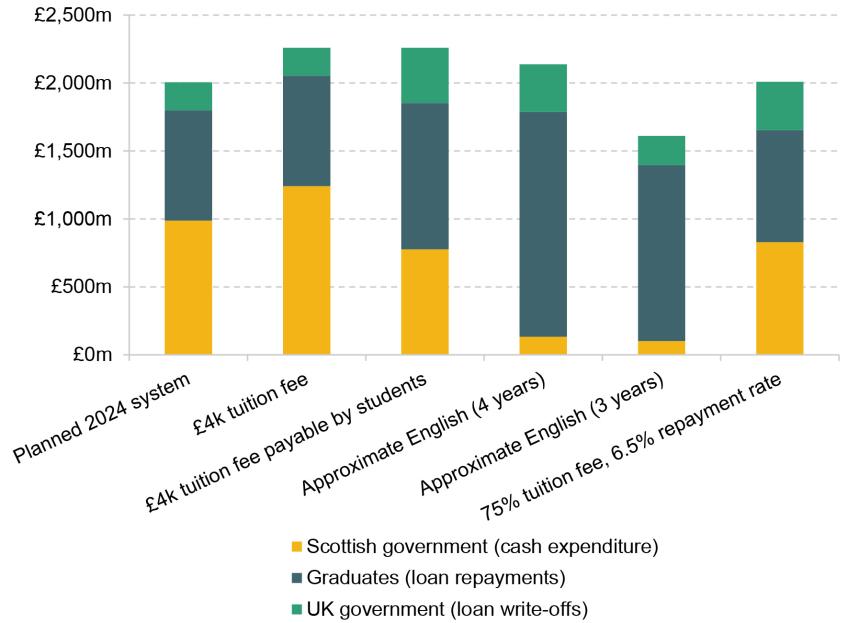

The trade-off on teaching resources is more acute. Under the current ‘free tuition’ model, any increases in per-student teaching resources for Scottish students would have immediate impacts on the Scottish budget. For instance, increasing the tuition fee from £1,820 to £4,000 would increase the resources available to universities for teaching by around 30%, more than restoring them to the same real value as in 2013–14. If these tuition fees were still paid on students’ behalf by SAAS, and there was no change to the number of funded places, this would add around £255 million to Scottish Government cash expenditure per cohort.

Another way to deliver the same increase in teaching resources would be to shift towards a funding model with a greater role for tuition fee loans. If this £4,000 per year tuition fee was payable by Scottish students and covered through a tuition fee loan, teaching resources per cohort would still rise by £255 million, but the Scottish Government would spend around £210 million less up front than under the 2024 system, as shown in Figure 5.9. Around £470 million of tuition fee loans would be issued to Scottish students, of which they could expect to repay around 57% (£264 million, or £8,900 each), with the remaining £200 million eventually written off. In this case, every additional £1 of cost to Scottish graduates would save the Scottish Government £1.77 – suggesting there might be ways to compensate Scottish graduates and still reduce demands on the Scottish budget.

Figure 5.9. Long-run cost of higher education borne by different parties, under different policies

Note: Assumes full take-up of living cost loans and bursaries. ‘£4k tuition fee’ increases tuition fee to £4,000 per year. ‘Approximate English (4 years)’ matches English teaching resources (including a £9,250 per year tuition fee payable by students) and living cost support and matches Plan 5 loan repayment terms. ‘Approximate English (3 years)’ also reduces the typical degree length to three years.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

Of course, this sharing of costs in the long run depends on this new arrangement still being considered to have ‘broadly comparable’ costs to arrangements in England. When there are changes to Scottish Government policy in this area, HM Treasury comes to a view as to whether costs remain broadly comparable, but there is not a fully formalised process for this. It is not clear exactly what measure of cost is used. The gross loan outlay per student (the AME spending component) may be of interest as this counts towards public sector net debt. In the long run, it is the eventual loan write-off which matters for the public finances, although this will be impacted by the choice of discount rate. Where there are different rates of loan take-up between the devolved administrations, it may matter whether costs are compared per student or per borrower.

As an illustration, we consider the impact if Scotland matched the system for 2023 starters in England in most respects, including the funding of teaching through a £9,250 per year tuition fee, approximately matching English students’ entitlements to living cost loans, and Plan 5 loan terms. The costs in this case are shown by the ‘Approximate English system (4 years)’ bar in Figure 5.9.

The combined effect of the different choices made by the Scottish Government with respect to higher education funding – except for the longer typical length of degrees at Scottish universities – is to increase the cost of educating each cohort of Scottish undergraduates to the Scottish Government by around £850 million (or £28,700 per student). For this, Scottish students receive around £10,900 less spending on their teaching, are entitled to around £6,500 more living cost support on average, and can expect to repay £28,300 less over their lifetimes. While the increase in Scottish Government spending is equivalent to £28,700 per student, graduates on average gain £23,800, and the UK taxpayer gains £4,900 per student in the form of lower write-offs.

If Scotland matched the English system, total loan outlay in this case (assuming full take-up) would be £2.0 billion per cohort, or around £67,500 per student, compared with £1.0 billion (£34,300 per student) under the system planned for Scotland in 2024. Around £350 million (£11,800 per student) would be written off in the long run, compared with around £200 million now27 . If HM Treasury was using loan outlay or this measure of loan write-offs to determine whether the costs of the Scottish student loan system were ‘broadly comparable’ – and particularly if it was comparing costs under the two systems for the same number of years of study – there may be some scope for the Scottish Government to increase teaching funding (or reduce pressure on the Scottish budget) without increasing contributions from Scottish graduates.

For instance, if three-quarters of the tuition fee of £1,820 per year were made payable by students (instead of paid on their behalf by SAAS), the Scottish Government would save approximately £150 million per cohort, which could be used to increase university funding or for other spending priorities. This could be combined with a cut in the repayment rate from 9% to 6.5%, reducing monthly repayments for Scottish graduates. Although graduates would make these lower loan repayments for more years, they would repay on average only around £400 more in total over their lifetimes (adjusted for inflation). The Scottish Government saving would be almost entirely paid for by an increase in loan write-offs to £355 million (£11,900 per student). This would be roughly in line with our estimate of the long-run cost to the UK government of Scotland switching to a fully English funding system, suggesting the cost of these loan write-offs may still be met by the UK government.

It is not clear how much scope there would be in practice for the Scottish Government to make such changes without bringing current funding arrangements into question. This is due both to uncertainty over the measure of cost that HM Treasury uses to reach a judgement, and to potential differences in the methodology used to model earnings and future loan repayments, which mean modelling by the UK or Scottish governments may deliver different results from the IFS Scotland Student Finance Calculator.

5.4 Conclusion

The Scottish Government plans to increase the generosity of living cost support for Scottish students next year, and to reduce monthly loan repayments from graduates from April. Under current funding arrangements, it can make such changes to loan outlay and eventual write-offs without impacting the Scottish Government budget. Indeed, if students took up their full entitlements to living cost support, the changes planned for 2024 would substantially increase average lifetime loan repayments amongst Scottish graduates (by around £5,000). They would also add around £100 million (£3,400 per student) to the cost of loan write-offs met by the UK government, although the UK government will still spend around £150 million less on loan write-offs for each cohort of Scottish students than if Scotland matched arrangements in England.

The Scottish Government has been less inclined to increase generosity where this would directly impact the resources available to fund competing policy priorities – which, under the current model of free tuition, include funding for undergraduate teaching. As a result, per-student teaching resources have been gradually eroded over time, and numbers of funded places for Scottish students tightly controlled, so that universities in Scotland are increasingly reliant on international student fees. The 2024–25 Scottish Budget suggests this trend is likely to continue next academic year.

There are no easy answers to increasing university funding, without increasing Scottish Government spending on higher education or requiring some contribution from students towards the costs of their tuition. Any attempt to significantly boost teaching resources through tuition fees would lead to significant increases in lifetime contributions from Scottish graduates. And any attempt to increase loan funding but to protect Scottish graduates from higher lifetime repayments could fall foul of HM Treasury’s ‘broadly comparable costs’ test.

References

Bank of England, 2024. Monetary policy report – February 2024. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2024/february-2024

Bolton, P., 2024. The value of student maintenance support. House of Commons Library, Research Briefing 00916, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn00916/

Drayton, E., Farquharson, C., Ogden, K., Sibieta, L., Tahir, I. and Waltmann, B., 2023. Annual report on education spending in England: 2023. IFS Report R290, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/annual-report-education-spending-england-2023

Emmerson, C., Farquharson, C., Johnson, P. and Zaranko, B., 2024. Constraints and trade-offs for the next government. IFS Report R295, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/constraints-and-trade-offs-next-government

Office for Budget Responsibility, 2023. Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023. https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-november-2023/

Ogden, K. and Phillips, D., 2023. Scottish universities and students are under pressure – and so is the Scottish budget. IFS Comment, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/scottish-universities-and-students-are-under-pressure-and-so-scottish-budget

Scottish Funding Council, 2023. University final funding allocations AY 2023-24. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/sfcan132023/

Scottish Government, 2021. Programme for Government 2021 to 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/fairer-greener-scotland-programme-government-2021-22/

Scottish Government, 2023a. Scottish Budget: 2024 to 2025. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-budget-2024–25/

Scottish Government, 2023b. Autumn Budget Revision 2023-2024 guide: finance update, https://www.gov.scot/publications/guide-abr-2023-24-finance-update-fpac/documents/