Introduction and summary

The UK general election on 4 July will determine the make-up of the House of Commons and, in turn, who forms the next UK government. For some of the issues at the heart of the election – such as defence spending and most taxes and benefits – the UK parliament and government make decisions for the UK as a whole. However, other issues – such as health and education – are devolved to the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Decisions in Westminster still matter though, because funding arrangements mean UK government tax and spending decisions affect how much the devolved governments can spend in their countries via the operation of the ‘Barnett formula’ (which bases changes in funding for the devolved governments on changes in spending in England). Table 1 provides a summary of which areas of policy are controlled directly by the UK government, and which are devolved to Scotland and Wales, meaning that decisions taken in Westminster do not apply in these nations but the funding available to their devolved governments may change.

Table 1. UK government and devolved government responsibilities

| UK government | Scottish Government | Welsh Government |

| Most taxation, including tax-free childcare | Income tax rates and bands on non-savings non-dividends income, property transactions tax, business rates, council tax (and other local taxation), landfill tax | Income tax rates on non-savings non-dividends income, property transactions tax, business rates, council tax (and other local taxation), landfill tax |

| Most benefits, and all policy around state pensions | Most disability benefits, winter fuel payment, cold weather payments, maternity and child food grants, ability to create new benefits (e.g. Scottish Child Payment), payment arrangements for universal credit, council tax reduction scheme, discretionary support schemes | Council tax reduction scheme, discretionary support schemes |

| Defence, foreign affairs, overseas aid, immigration and asylum | ||

| Policing and justice for England and Wales | Policing and justice for Scotland | |

| Rail infrastructure for England and Wales | Rail infrastructure for Scotland | |

| Broadcasting, betting and gambling, competition policy, energy, financial services, postal services, telecommunications, some economic development policies (e.g. UK Shared Prosperity Fund, Levelling Up Fund) | Health, education, childcare (excluding tax-free childcare), local government, housing, most transport, rural affairs, environment, sports and arts, most economic development | Health, education, childcare (excluding tax-free childcare), local government, housing, most transport (excluding rail infrastructure), rural affairs, environment, sports and arts, most economic development |

| Competition policy, currency, employment regulation, macroeconomic management | ||

| Full borrowing powers | Limited borrowing powers | Limited borrowing powers |

Working out exactly how the policy proposals contained in the parties’ manifestos will affect Scotland and Wales can still be difficult though – especially because the parties sometimes try to blur the boundaries between national and devolved responsibilities when describing their policies. This report is therefore our attempt to provide a guide to the impact of tax and spending policy proposals on Scotland and Wales. We focus on the two largest UK parties (the Conservatives and Labour), as well as the SNP in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales.

At a high level, while Labour propose slightly higher taxes and spending than the Conservatives, both parties’ manifesto proposals imply cuts to investment spending and modest increases in overall day-to-day spending on public services. It would be up to the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales to determine how to allocate their funding across services, but facing the same pressures on healthcare as England, the devolved governments would likely need to make cuts to at least some ‘unprotected’ services, unless they were to increase their own taxes. The SNP propose a substantial boost to both investment and day-to-day public service spending UK-wide, as well as increases to working-age benefits, funded by higher taxes and higher borrowing. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the boost to day-to-day spending would probably be enough to avoid cuts to ‘unprotected’ services. The way the SNP propose to part-fund these increases (via income tax increases largely only applying outside of Scotland) means that the boost to spending in Scotland would be smaller. Plaid Cymru do not provide a costed set of proposals on tax and spending, making their overall plans hard to assess. But it is clear that they favour higher taxes, borrowing and spending than both Labour and the Conservatives, and they argue for reforms to funding allocations that they claim would benefit Wales.

Key findings

1. Most of the tax changes proposed by the Conservatives and Labour would apply nationwide, including cuts to National Insurance contributions from the Conservatives and plans to levy VAT on private school fees from Labour. The exception is the Conservatives’ proposed stamp duty land tax cut, which would apply only in England and Northern Ireland. Taxes would rise as a share of national income under both, but by a bit more under Labour than under the Conservatives. Plaid Cymru and the SNP propose tax changes at the UK level that would involve bigger increases overall than under either Labour or the Conservatives, as well as further tax devolution. Somewhat surprisingly, the biggest tax change proposed by the SNP (for the UK government to adopt the Scottish Government’s existing income tax bands and rates) would largely only apply outside of Scotland.

2. The Conservatives propose to reduce benefit spending compared with forecasts but do not explain how they would fully deliver the reductions. Any reforms to disability benefits would not directly apply in Scotland but would instead affect the Scottish Government’s funding. This would mean that, unless it cut the generosity of its own benefits, it would have to raise taxes or cut other spending. Labour have pledged to review universal credit and incapacity benefits, which apply across the UK, but make no concrete pledges. Both Plaid Cymru and the SNP propose substantial increases in the generosity of the benefit system, particularly targeted at families with children. They also ask for further devolution of benefits policy.

3. The small tweaks to public service spending in the Conservative and Labour manifestos would still likely leave many unprotected areas of spending and investment facing cuts post-election. Plaid Cymru do not say how much they think should be spent, but their proposals for specific services would require higher spending. The SNP propose significant top-ups to day-to-day spending and investment that would be more than sufficient to avoid cuts to unprotected areas and investment in the rest of the UK. However, the way the SNP propose to fund spending increases in the rest of the UK means that Scotland would not see as big a boost to spending as England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

4. The plans set by the Conservatives and Labour would, on current forecasts, be just about enough for government debt to fall as a share of national income by 2028–29. But the difficulty of forecasting means that in reality, even if the parties’ plans were stuck to in full, there is little more than a 50:50 chance of debt actually falling in that year. Plaid Cymru do not provide sufficient information to calculate the impacts of their policies on borrowing and debt, but both would likely be higher than under Labour or Conservative plans. The SNP propose higher borrowing, within a new set of fiscal rules, but which would leave debt increasing as a share of national income into the longer term.

5. Both the Conservatives and Labour reject Scottish and Welsh independence. Plaid Cymru and the SNP are, unsurprisingly, in favour. While correctly highlighting the austerity implicit in the main UK parties’ spending plans, the SNP and Plaid Cymru skirt around the significant public finance challenges an independent Scotland and Wales would face in at least their first few years, necessitating tax rises or spending cuts.

6. The Conservatives and Labour say relatively little about devolution to Scotland or Wales. Plaid Cymru and the SNP would like substantial further devolution of spending and regulatory policies, including ‘levelling up’ funds. Here, Labour propose some role for ‘representatives’ of Scotland and Wales, but it is not fully clear what role that means for their devolved governments as opposed to these countries’ Westminster MPs. The Conservatives propose to abolish one of the main levelling up funds from 2028 to fund their UK-wide ‘National Service’ scheme. The SNP and Plaid Cymru both propose substantial further devolution to their nations – with the SNP’s proposals for ‘full’ tax and social security proposals requiring an entirely new funding model for Scotland.

What about the other parties?

You can read IFS researchers’ reaction to other parties’ proposals here. Broadly speaking, their public service spending measures would typically not directly apply to Scotland or Wales but would affect funding for the devolved governments (increasing it in the case of the English and Welsh Greens and Liberal Democrats, and decreasing it in the case of Reform UK). Tax and benefit policies typically would apply across the UK, with the exception of mooted changes to disability benefits, which are devolved to Scotland.

The Liberal Democrats propose higher taxes, borrowing and spending than both Labour and the Conservatives. But their proposals are dwarfed by the Greens’ proposed tax, borrowing and spending increases. Conversely, Reform overall propose large cuts to taxation and spending. For the Greens, tax rises are likely to raise considerably less than suggested, while for Reform tax cuts would cost much more, and spending cuts save less, than projected.

1. Tax policy proposals

Most of the tax changes proposed by the Conservatives and Labour would apply nationwide. This includes the Conservatives’ pledge to further cut National Insurance contributions for employees and the self-employed, and Labour’s plans for VAT on private school fees and higher taxes on private equity returns – although the relatively small numbers of high-income individuals and families in Scotland and especially Wales mean a smaller fraction of the population would be affected by Labour’s proposals than in England. The key exception is the Conservatives’ proposal to maintain the stamp duty tax threshold for first-time buyers at £425,000 (rather than it reverting to £300,000). This tax is devolved to Scotland and Wales, so this policy would not apply in these nations. Instead, the devolved governments would receive an equivalent amount of money, which they would be free to spend or use to cut their own taxes.

Both the Conservatives and Labour have confirmed they would maintain the existing freeze in income tax and National Insurance thresholds until April 2028. These freezes directly apply in Wales as in England and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, the situation for income tax is more complex, reflecting the fact that apart from the tax-free personal allowance, tax bands as well as rates are devolved to the Scottish Government, unlike in Wales. This means that while the freeze in the personal allowance applies directly in Scotland like in the rest of the UK, it is up to the Scottish Government whether to freeze the other tax thresholds and bands on income other than from savings and dividends. If thresholds are frozen in the rest of the UK though, UK government funding for the Scottish Government is adjusted so that it would also need to freeze its thresholds if it also wanted to benefit from the additional revenue that freezing tax thresholds provides.

Both Plaid Cymru and the SNP propose changes to UK-wide taxes and the devolution of new tax powers.

On UK-wide taxes, Plaid Cymru argue for increases in taxes on energy companies, the equalisation of capital gains tax rates with income tax rates, and investigating increases in National Insurance contributions for higher earners and the introduction of a wealth tax. They also propose further income tax devolution and, while not fully explicit, the manifesto suggests that Plaid Cymru would use enhanced powers to raise taxes on higher earners, as in Scotland.

The SNP’s headline proposal on taxation is a tax increase that would largely not apply in Scotland – replicating Scotland’s system of income tax rates and bands in the rest of the UK. This would see reductions in bills of up to £23 per year for those with incomes of less than about £29,000 per year, but would see income tax increase substantially for those with higher incomes. For example, someone with an income of £50,000 a year would see their income tax rise by £1,540 per year, while someone with an income of £125,000 would see an increase of £5,220. The SNP estimate this would raise £16.5 billion a year for the UK government by 2028–29. Other proposals, which would apply UK-wide including in Scotland, include putting VAT on private school fees (as Labour have proposed), taxing share buybacks and increasing the bank corporation tax surcharge and bank levy (like the Liberal Democrats), and a gambling levy on top of existing gambling taxes.

The SNP also call for significant further tax devolution to Scotland – including full powers over income tax, as well as the devolution of National Insurance contributions, VAT and the power to levy windfall taxes on ‘excess’ profits (which they say should apply more widely than just the energy sector). Devolving income tax on savings and dividends is a sensible idea. Devolving National Insurance contributions would allow for better integration with income tax. Together, these proposals could enable beneficial reforms to how different forms of income are taxed. However, careful consideration would have to be given to how any reforms would affect contributory benefits such as the state pension (which are linked to National Insurance contributions). And devolving all income tax rules would add complexity for some taxpayers and the tax authorities (e.g. if different expenses are tax-deductible for different employees living in different parts of the UK). VAT is a particularly tricky tax to devolve, potentially creating trade barriers between Scotland and the rest of the UK. If it were devolved, the SNP propose cuts to VAT for hospitality and tourism in Scotland, as well as a few other items, which would benefit the targeted sectors but increase complexity in the system.

2. Benefit policy proposals

The Labour party’s manifesto contains no concrete policies on working-age benefits. However, it does say that they would ‘review Universal Credit so that it makes work pay and tackles poverty’ and allude to a plan to reform or replace the assessment that determines eligibility for incapacity benefits. Both of these relate to benefits that apply UK-wide, but what changes Labour have in mind is unclear. Changes to universal credit that affect the numbers and characteristics of those eligible would also affect eligibility for and spending on several of Scotland’s devolved benefits (such as the Scottish Child Payment), where eligibility is linked to receipt of universal credit.

The Conservative party does suggest one specific increase in the generosity of the working-age benefit system – increasing the threshold at which child benefit is withdrawn, and making withdrawal dependent on family income rather than the income of the highest earner in a couple. This would apply across the UK.

The Conservatives’ main pledge though is to reduce other benefit spending by £12 billion compared with current forecasts. Again, details on how to achieve this are sparse – some of the policies highlighted are already UK government policy and therefore are appropriately already built into the public finance forecasts, while others are just small. The manifesto focuses particularly on disability benefits, where caseloads and expenditure have increased rapidly since the pandemic and are forecast to continue to. If reforms were made to disability benefits (such as personal independence payment) to reduce caseloads or expenditure, this would apply in Wales but not Scotland, where most disability benefits are devolved. However, any reduction in spending in the rest of the UK would reduce the funding provided to the Scottish Government for disability benefits. The Scottish Government would need to dip further into its general funding to pay for its benefits or try to cut back spending north of the border too.

Both Plaid Cymru and the SNP argue for increases in the generosity of the benefit system at a UK level. Both call for the abolition of the two-child limit in universal credit, as well as the restoration of the link between local housing allowance (LHA) rates in universal credit and local rents (LHA rates are currently frozen). In addition, they propose abandoning planned changes to how people’s eligibility for top-ups to universal credit due to disability are determined (which would see the basis change from whether the disability is judged to affect a person’s ability to work, to whether it causes them to experience additional living costs).

Most significantly, both the SNP and Plaid Cymru propose an ‘essentials guarantee’ in the benefit system. Plaid Cymru say this would be £120 per week for an individual adult and £200 per week for a couple (excluding housing costs support), based on figures calculated by the Trussell Trust and Joseph Rowntree Foundation, to ensure people can properly afford food and utilities if they are in receipt of benefits. The SNP estimate that their ‘essentials guarantee’ would cost £20 billion per year by 2028–29 across the UK as a whole.

Plaid Cymru also call for a £20 per week increase in child benefit, costing something like £15 billion a year across the UK as a whole, or £600–700 million a year if undertaken in Wales as part of benefit powers they want devolved. In addition, Plaid Cymru suggest a set of changes to the operation of universal credit, including shorter waiting times for first payments and special rules for calculating farmers’ entitlements.

The SNP propose increases in universal credit for the under-25s and for couples where one adult is aged above and the other below the state pension age (this group was previously entitled to the more generous ‘pension credit’). They would also like powers over setting the local housing allowance devolved.

All four parties support retaining the triple lock on the state pension (with the Conservatives and Plaid Cymru also proposing to link the income tax threshold to this increase too). While it is legitimate to want to protect the value of the state pension relative to both earnings and prices, the design of the triple lock does this in a way that makes the long-term generosity of the pension depend not only on long-term changes in earnings and prices, but also on the year-to-year volatility and correlation of those changes. There are better ways to provide protection to the value of the state pension that avoid this problem and reduce uncertainty about the future generosity and cost of pensions to both the population and government.

3. Spending on public services

In the March Budget, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt reiterated plans for day-to-day public service spending to increase by 1% a year above inflation between 2024–25 and 2028–29, and freeze investment spending in cash terms (implying real-terms cuts). Analysis from IFS has shown that given the funding that would be needed to deliver the NHS’s long-term workforce plan, protect the total schools budget in England from cuts, and meet commitments on aid, defence and childcare, other areas of day-to-day spending could see cuts of £10–20 billion a year by 2028–29.

Under such plans, the devolved governments’ funding would almost certainly increase – perhaps by about 1% a year above inflation, in line with the average for overall public spending. But because they face the same healthcare spending pressures, they would likely need to make cuts to other parts of their budgets too.

How would the parties’ manifestos change this picture?

For the Conservatives and Labour, not by much.

Taken together, the Conservatives’ plans would leave non-benefit spending little changed compared with the plans set out by the Chancellor in March. But because they propose increases to defence spending funded by cuts elsewhere, their plans would somewhat increase the pace of cuts to ‘unprotected’ day-to-day spending. In contrast, Labour’s plans imply an increase of around £10 billion a year by 2028–29, split roughly 50:50 between day-to-day spending and (mostly green) investment spending. Therefore, while they claim there would be ‘no return to austerity’, their plans would only modestly reduce the pace of cuts implied to unprotected day-to-day spending if other pledges – for example, on meeting the English NHS’s long-term workforce plan – are taken seriously. In addition, Labour’s green investment boost would still see overall investment fall in real terms. Thus, for at least parts of the public sector, further spending cuts would appear to be coming unless Labour’s spending plans were further topped up via higher borrowing or taxation.

It is also worth noting that most of the specific policies on health, education and social care in the Conservative and Labour manifestos are England-only, but would affect how much funding the devolved governments receive under the Barnett formula. This is true, for example, for Scottish and Welsh Labour’s pledges on NHS appointments and on teacher numbers – the devolved governments would receive funding as a result of these pledges but it would be up to them how to use that funding, which may not be for the same purposes a Labour party in government in Westminster would use it for. Pledges on police numbers by both the Conservatives and Labour would directly affect Wales, where justice and policing are not devolved, but not Scotland, where these responsibilities are devolved.

Plaid Cymru hint at, and the SNP are explicit about, much bigger top-ups to existing spending plans at a UK-wide level.

While Plaid Cymru do not set out any specific spending plans (or provide a policy costing document), their ambitions for free personal care, universal free childcare from age 1 and universal free school meals in Wales would deepen cuts for unprotected services unless spending were increased at either a UK-wide or Welsh level. They also suggest reforms to funding arrangements for the devolved governments, including replacing the Barnett formula with a needs-based approach, which while broadly sensible, probably would not boost funding for Wales in the short term as they seem to believe.1

The SNP propose an £18 billion boost to day-to-day spending in 2028–29, which they say is to avoid the cuts to unprotected services implicit in current UK government spending plans. They also propose a further £16 billion boost to NHS spending in England on top of the increases we estimate would be needed to meet the NHS’s long-term workforce plan. Taken together, this would be a genuinely big increase in spending compared with current plans – meaning average annual real-terms growth in day-to-day public service spending of perhaps 2.4–2.8% as opposed to 1%.

Both increases would generate additional funding for the Scottish Government (and other devolved governments) via the Barnett formula. However, because they would be part-funded by an increase in income tax rates that would largely not apply in Scotland, the boost to the Scottish Government’s funding would be proportionately less than the boost to public spending in the rest of the UK. Based on the SNP’s estimate of £16.5 billion a year in revenues from the income tax changes in the rest of the UK, this ‘shortfall’ could amount to around £1.1 billion a year. This means that if the SNP did want to top up NHS spending by the equivalent of £1.6 billion it says Scotland would receive as a result of higher NHS spending in England, the Scottish Government would still probably need to make cuts to some unprotected services, unless income tax was further raised in Scotland.

On the investment side of the equation, the SNP propose cancelling the real-terms cuts to investment spending pencilled in by the Chancellor between now and 2028–29. They also suggest an immediate £28 billion a year boost to investment in the ‘green economy’. In practice, spending this additional investment well would require it to be ramped up more gradually.

4. Public finances and borrowing

Taken together, the Conservatives’ and Labour’s tax and spending proposals have little impact on the overall public finances – relatively small tax changes are largely offset by relatively small spending changes. In both cases, under existing forecasts, debt would continue to rise as a share of national income for the next few years, and fall very slightly in 2028–29. The margin for error is small and uncertainty high though. Even if these plans were implemented exactly as they stand, the chances of debt actually falling in five years’ time, as required to meet both parties’ fiscal rules, is little more than 50:50.

The lack of figures in the Plaid Cymru manifesto makes it difficult to say exactly what their plans would mean for borrowing and national debt, but it seems unlikely they would borrow less than the main UK parties, given their large and concrete spending proposals and vaguer tax proposals.

The SNP are explicit that they would increase borrowing – to fund the £28 billion boost to investment in the green economy they call for. To enable this, they propose new fiscal rules based on public sector net worth and on debt servicing costs as a fraction of revenue. There is merit in tracking both of these. But spending on debt interest is already running at much higher levels than we have been accustomed to in recent decades, and the SNP plans would involve higher borrowing and public sector net debt rising as a share of national income for longer (and potentially much longer) than the Conservatives’ and Labour’s plans. That is particularly true because their biggest revenue raiser is not in fact a tax measure but the assumed revenue boost from additional economic growth resulting from rejoining the EU. While the figure they assume (£30 billion a year) is not an unreasonable one for the long term if the UK did rejoin the EU, the chances of this happening in the coming parliament look slim given Conservative and Labour party statements. In the absence of such revenues, more borrowing would be required for the SNP’s spending pledges.

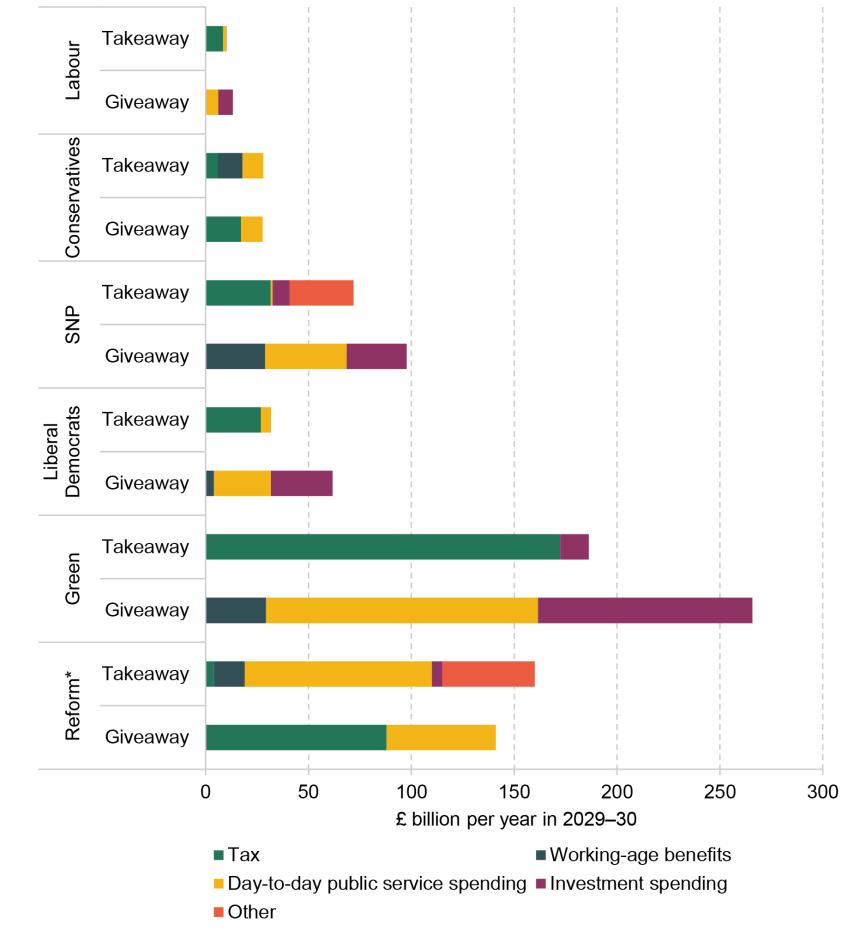

Figure 1 compares the relative size of the ‘giveaways’ (tax cuts or spending increases) and ‘takeaways’ (tax increases or spending cuts) in 2029–30 set out in the parties’ manifestos, relative to the plans set out by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt in March. It shows clearly how modest in fiscal terms the changes proposed by Labour and the Conservatives are, compared with the plans set out by the SNP and particularly the Greens and Reform UK. (Plaid Cymru’s lack of policy costings means it is not possible to include them in this figure). Where giveaways exceed takeaways, parties’ own costings increase borrowing (and vice versa) compared with the plans set out by the Chancellor in March.

Figure 1. The tax and spending ‘giveaways’ and ‘takeaways’ proposed in the parties’ manifestos, 2029–30

* Reform figures are averages per year, not 2029–30. * Reform figures are averages per year, not 2029–30.

Note: ‘Other’ for SNP is an assumed boost to revenues from rejoining the EU. ‘Other’ for Reform is assumed savings on debt interest payments due to reductions in interest paid on reserves held at the Bank of England, and an assumed boost to revenues as a result of growth they say would result from their other tax and spending measures. All costings provided by parties are taken as given for the purposes of this graph – this should not be taken as an endorsement of those costings.

Source: Parties’ manifesto costing documents.

Servicing the national debt (i.e. paying interest and repaying borrowed money) is an issue for the whole of the UK, including Scotland and Wales: on average, it is expected to account for 8p of every £1 of government spending across the UK over the next five years. This compares with 4p in every pound in 2019–20, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and recent increases in interest rates.

5. Independence

One area where both the SNP and Plaid Cymru fail to properly discuss the public finance implications – and hence the potential tax and spending implications – is independence.

The SNP put Scottish independence front and centre of their manifesto and say that there would be a mandate for a second referendum if they win a majority of Scottish seats. Plaid Cymru focus far less on independence, but their manifesto restates it as a goal, and proposes a Green Paper on how it could be achieved. Both the Conservative and Labour manifestos reaffirm their parties’ opposition to independence and a second Scottish independence referendum.

The reason independence is a public finance issue is twofold.

First is that independence would affect the economy, which in turn would affect the public finances. The SNP and Plaid Cymru highlight potential economic benefits from independence, including a boost to trade and growth from rejoining the EU – which in the long term is possible, although not certain. In the short term, however, independence would likely prove economically disruptive, especially if it entailed additional trade barriers with England (which would be the case if an independent Scotland or Wales rejoined the EU) – which is currently by far the largest trading partner of both Scotland and Wales.

Second, both Scotland and Wales receive much higher levels of public spending per person than the UK as a whole. In Scotland’s case, revenues per person are similar to the UK average, while Wales’s relatively low incomes and weaker economy mean its tax revenues per person are much lower than in the UK as a whole. This means that, in effect, Scotland and Wales receive fiscal transfers from the UK that would be lost at independence. Both an independent Scotland and an independent Wales would start life with much higher levels of borrowing, relative to their size of the economy, than the UK as a whole and these would need to be addressed. The SNP manifesto skirts around this issue, while Plaid Cymru cite research suggesting a manageable deficit, but which, among other things, assumes the UK government keeps paying state pensions post-independence (which seems highly unlikely).

In the longer term, then, there is a possibility that a different policy mix could boost the economy and improve the public finances of an independent Wales or Scotland, allowing higher spending or lower taxes. But in the first decade at least (and probably much longer in Wales given its particularly weak fiscal position), the opposite would almost certainly be true: taxes would need to be raised or spending cut significantly to address the large budget deficits these newly independent nations would start life with.

6. Devolution and ‘levelling up’

What about devolution within the UK?

We have already discussed the tax devolution that Plaid Cymru and the SNP would like. In contrast, neither the Conservatives nor Labour mention tax devolution in their manifestos. Indeed, more generally, there is relatively little on devolution to either Scotland or Wales in either of their manifestos. Moreover, while not explicitly mentioned in the manifesto itself, senior Labour figures appear to have ruled out devolving policing and justice to Wales, despite the Welsh Labour government requesting this. (The Labour manifesto implicitly confirms this by repeatedly referring to justice and policing policies applying to both England and Wales.)

Labour do pledge more of a role for representatives of Scotland and Wales in allocating ‘levelling up’ funding, although there is uncertainty about the roles of the Westminster-based Scotland and Wales offices and the devolved governments: reporting in Wales suggests responsibility would be shared with the Welsh Government, whereas reporting in Scotland has emphasised the role of the Scotland Office. Both Plaid Cymru and the SNP have called for this funding to be fully devolved.

The Conservatives propose to wind up the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF), a £1.5 billion fund aimed at levelling up, from 2028 to part-fund its plans for National Service for 18-year-olds across the UK (including Scotland and Wales). Currently, Wales receives by far the highest funding per person through the UKSPF of any nation or region, partly because it is one of the most economically disadvantaged of the country, and partly as a relic of the specific design of previous EU regional development funding rules which the UKSPF replicated when it was introduced following Brexit. Analysis from IFS suggests that Merthyr Tydfil and Blaenau Gwent would lose the greatest amounts of funding per person from abolishing the UKSPF (£273 and £246 per resident per year, respectively), with Welsh councils losing an average of just over £100 per resident per year. In Scotland, the biggest hit would be to the Islands areas (around £50 per resident per year), with the average loss to Scottish councils amounting to £23 per resident per year.

Plaid Cymru’s manifesto calls for the devolution of policing and justice to the Welsh Government, as well as rail infrastructure funding. Their preference for needs-based funding does not extend to these areas in which a population-based allocation would mean more money for Wales (crime is lower and rail usage much lower in Wales than in England). As part of their proposal to devolve rail infrastructure funding, Plaid Cymru also say that the Welsh Government should receive funding as a result of the construction of High Speed 2 (which the Scottish and Northern Irish governments do receive, because rail infrastructure funding is already devolved to these nations). This would amount to around £4 billion over the lifetime of the HS2 project.

Beyond the party’s call for specific tax and benefit powers, the SNP manifesto also calls for ‘full’ tax and social security devolution. This would be a huge change and would require broader changes to the UK’s fiscal architecture, including the overall level of funding provided to Scotland and how Scottish taxpayers contribute to UK-wide functions (such as defence, foreign aid and servicing the national debt).