The Labour party has promised to introduce free breakfast clubs in all primary schools in England. Around 12% of state schools in England already offer a taxpayer-subsidised breakfast club through the National School Breakfast Club Programme (NSBP), but Labour’s proposal would expand breakfast clubs to all primary schools in England, continue existing provision for low-income pupils via the NSBP (which is set to run out in July 2025) and increase the generosity of the funding.

The party argues that this will improve learning, tackle high rates of absence post-pandemic, support families through cost-of-living pressures, and help parents to work by offering before-school childcare. But achieving these aims – and the cost of the programme – really depends on the details.

What is the current breakfast club offer?

In England, schools with at least 40% of pupils from income-deprived areas can receive a subsidy covering three-quarters of food and delivery costs under the NSBP. Around 12% of state schools in England currently take part in the scheme, funding for which ends in July 2025. Outside these publicly funded breakfast clubs, several charities, such as Magic Breakfast, support or deliver breakfast clubs, and some schools pay for clubs out of their own budgets. Primary schools in Wales have been able to opt into funding to provide free breakfasts since 2004.

What are the benefits of breakfast clubs for children?

The term ‘breakfast club’ can mean different things. At its simplest, it refers to the provision of breakfast integrated into the usual school day (typically in the classroom at the start of the first lesson). In contrast, a more ‘traditional’ breakfast club provides a space for pupils to eat breakfast and socialise before the school day begins.

Both approaches can benefit children by improving nutrition. In Wales, free breakfast clubs helped children eat more healthily and reduced skipping breakfast. Breakfast clubs in England have also been shown to raise attainment at age 7; even pupils who did not attend the clubs benefited from a better, calmer classroom environment. However, studies often find only small improvements (if any) on absences: in England, breakfast clubs led to reductions of around half a day of absence per year per pupil – not a solution, on its own at least, to current high rates of absence.

A ‘traditional’ model of breakfast club – one that takes place in a school canteen, for instance – also changes the environment for children, bringing them together in a group before the school day starts. There is some evidence that this opportunity to socialise with peers and adults before school has its own benefits for attainment.

Whether these benefits are realised also depends on what pupils have access to already. Pupils in schools where breakfast clubs were not previously offered may see larger gains, particularly disadvantaged children in schools falling below the threshold for NSBP support. In other cases, Labour’s policy may simply change who is paying for existing provision. While this may ease the budgets of schools and families or allow schools to offer more generous programmes, the benefits for children may be more muted.

Breakfast clubs as childcare and cost-of-living support

Breakfast clubs could also help parents. Most obviously, children getting breakfast at school will not need to be fed at home, potentially reducing pressures on family budgets. But the financial burden of breakfast foods tends to be much lower than other meals. Most food provided at breakfast clubs is surprisingly cheap: spending on food under the National School Breakfast Club Programme comes to only around £40 for a year’s worth of breakfasts for one child.

A potentially more valuable benefit for parents, at least from traditional breakfast clubs, is access to free or low-cost before-school childcare. For those currently using them intensively, breakfast clubs can be a noticeable cost for families: based on recent patterns of usage and spending, a parent whose child attends an average breakfast club five days a week during term time would spend £760 each year. So a proposal to make breakfast clubs universally free could save these families a meaningful amount.

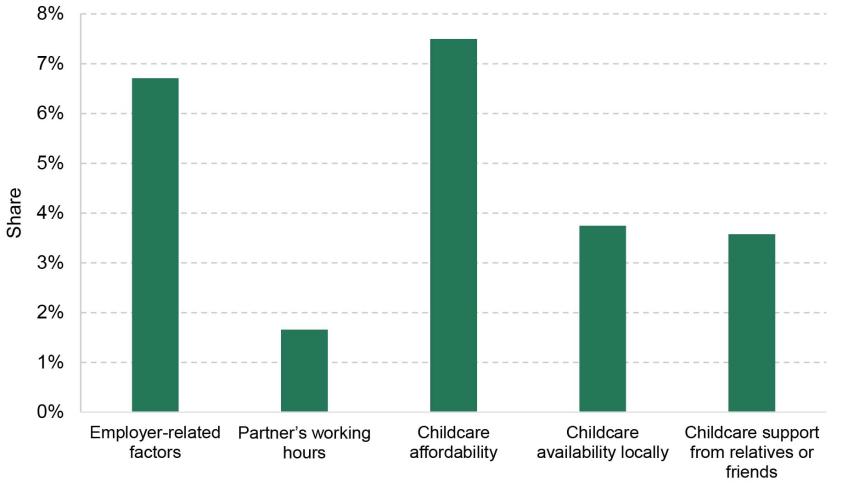

Overall, though, breakfast clubs seem to be one of the less troublesome parts of the school-age childcare system. Around 20% of mothers whose youngest child is in primary school are not in employment; another 35% work part-time. In 2018, one in ten mothers with school-aged children reported that they would prefer to be working more hours and were specifically constrained by a lack of available or affordable childcare (Figure 1). Yet parents seem more concerned by childcare after school and during holidays: while more than one in four families with children aged 0–14 report wanting greater access to after-school clubs or leisure activities, and one in five cite challenges with childcare availability during school holidays, one in twelve would like to access more breakfast club provision.

Figure 1. Self-reported factors that constrain mothers’ paid working hours, 2018

Note: Among all mothers of primary-school-aged children (not necessarily those whose youngest child is in primary school). Respondents were asked whether they would like to increase hours of paid work and, if so, what would help increase hours. Respondents could give more than one answer. Respondents who reported not wanting to increase hours were not asked about barriers and therefore are included as zeros.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents 2018.

How much could breakfast clubs cost?

The options for designing a breakfast club come with different costs, as well as different benefits. Labour’s manifesto committed to spending £315 million on breakfast clubs in 2028–29, but without giving further details of what model of provision they intend to adopt or what they expect take-up to be.

A food-only model, such as breakfast in the classroom, is cheaper than a programme that combines food with childcare which requires more staff time, typically from teaching assistants and teachers. Schools may achieve this through extra paid staff time, reallocating staff time from other tasks, or recruiting volunteers. Based on the experience of the national school breakfast programme, the estimated annual cost today would be around £55 per pupil participating for food-only provision and double that (around £110) for a ‘traditional’ before-school breakfast club1 . Labour’s manifesto offers £315 million overall in 2028; this could be enough to fund all primary school pupils under a food-only model, or 60% of pupils if the party plumps for a traditional breakfast club with some childcare element.

While the latter represents a far-from-universal take-up rate, experience suggests that most pupils do not take up breakfast club provision on offer. An evaluation of breakfast clubs in England found take-up rates of around 20%, similar to take-up rates of 20–25% in Wales. Take-up of the National School Breakfast Programme in England is somewhat higher, at around 35% (though take-up of traditional breakfast clubs is less than half that rate). All would be consistent with the total budget that Labour has set out. The funding pot would also allow for reasonable rises in take-up, which have been documented during expansions of breakfast clubs in other contexts.

Summary

Labour’s policy would turn existing targeted breakfast club provision into a universal offer, accessible to all primary school pupils in England. Compared with other policy options – including universal free school meals mooted in Labour’s 2019 manifesto – breakfast clubs can be a cheap way to provide nutritional support to children and have been shown to boost grades. Scope for reducing school absences is smaller – breakfast clubs do not appear to be up to the task of tackling the significant attendance challenges that schools currently face.

Whether the programme delivers savings for families and childcare support really depends on the details of the chosen programme and how that policy is implemented. There remains a genuine question of the value families place on childcare support in this format. The Labour manifesto is silent on details, but its overall programme is comfortably enough to provide at least some childcare even at high levels of take-up.

More broadly, Labour’s proposed breakfast clubs are part of a set of measures that would involve channelling support for children and families through schools, from proposals for mental health workers in schools to supervised toothbrushing. This kind of mission creep may present additional challenges for schools already struggling with pay, workload and recruitment pressures for teachers and teaching assistants – and with little in the way of guaranteed increases to core funding to help them cope.