Funded by the Nuffield Foundation

Under the current higher education (HE) funding system in England, the government pays around £22 billion to fund the education of each cohort of around 480,000 England-domiciled full-time undergraduate students studying anywhere in the UK. This covers spending on students at higher education institutions or at alternative providers that are eligible to charge full tuition fees. It includes payments to universities (largely tuition fee payments funded by government student loans, but also teaching grants) and to students towards their living costs while at university. In the long run, the government gets back part of this initial outlay as graduates make repayments on their student loans. Under current rules and economic projections, the long-run cost will be mostly borne by graduates, but how much exactly is hugely uncertain. (Students from other parts of the UK are eligible for greater government support, so for them a larger share of the long-run cost is borne by the taxpayer.)

The HE system in England is funded primarily through tuition fees. Due to binding caps on the level of tuition fees that institutions can charge, nearly all courses cost between £9,000 and £9,250 per year. Direct grants for universities only amount to around £1,150 per student per year on average, with only some ‘high-cost’ subjects attracting a substantially higher level of direct government funding. This means that for most courses, total resources per student amount to just over £10,000 per year.

For most English-domiciled students, all of this funding is initially provided by the taxpayer. This is because English-domiciled students studying for their first undergraduate degree can take out government-subsidised loans to cover the full cost of tuition fees. In addition, they are eligible for so-called maintenance loans to cover part of their living costs. These loans accrue interest, and are repaid on an income-contingent basis: graduates repay 9% of their income over a threshold and any outstanding loan is written off at the end of the repayment period with no adverse consequences for graduates.

Consequences of the funding model

The current system ensures that students attending university for the first time do not need to pay any up-front fees to attend university and have access to living costs support in the form of maintenance loans. However, the amount of maintenance loan a student is eligible for depends on their parents’ income, and even the maximum rates are low compared with living costs in many parts of the UK. As a consequence, most students spend more than the maximum maintenance loan, and many students who do not receive parental transfers rely on part-time work to fund their studies.

For graduates, this system means that those with low earnings later in life contribute very little towards the cost of their degrees, and will not clear their loans by the end of the repayment period. For these graduates, the system therefore functions like a graduate tax: moderate changes to the repayment rate, repayment threshold or repayment period essentially constitute tax rises or cuts. In contrast, moderate changes in the loan interest rate have no effect on their lifetime repayments.

For high-earning graduates, who can expect to clear their loans before the end of the repayment period, the system functions more like a standard loan contract. For these graduates, the key parameter of the system is the interest rate: the higher the interest rate, the more they repay, provided they do not make voluntary repayments. In contrast, moderate changes to the repayment rate, repayment threshold or repayment period will mostly affect how quickly these graduates pay off their loans rather than how much they repay in total.

On the university side, a key consequence of this system is that the bulk of teaching funding is not centrally controlled and therefore not subject to short-term government budget pressures: spending on student loans automatically rises in proportion to the number of loan-eligible students admitted. This is advantageous for universities but makes it more difficult for the government to control total spending.

A more subtle effect, highlighted in our previous work and emphasised in the 2019 Augar Review, is that funding varies less across subjects than the cost of provision: in many cases, lab-based subjects are likely to be cross-subsidised by social science and humanities subjects that are cheaper to teach. This gives universities an incentive to shift provision towards subjects that are less expensive to teach, which may not align with government priorities.

Past changes to the system

Since the current system of university funding in England was introduced in 2012, it has been subject to constant tinkering by successive governments. According to stated government policy, the fee cap is meant to increase with (RPIX, the Retail Prices Index excluding mortgage interest payments) inflation every year, but it has in fact only been increased once (in 2017) and is set to remain frozen until 2025. As a result, per-student spending has been declining in real terms and universities have been particularly exposed to rising costs, complicating their financial planning.

On the repayment side, the repayment threshold was supposedly linked to average earnings, but was frozen in nominal terms before it could increase for the first time in 2016 (supposedly until 2021). In a surprising change of policy, it was then raised to £25,000 in 2018 and rose with average earnings until 2021. Since then, it has been frozen again at £27,295, and is set to remain frozen until 2025. From 2025 onwards, the threshold will now supposedly be indexed to RPI inflation instead of average earnings. These policy changes constitute large retrospective changes to student loan conditions and have been criticised by consumer rights advocates.

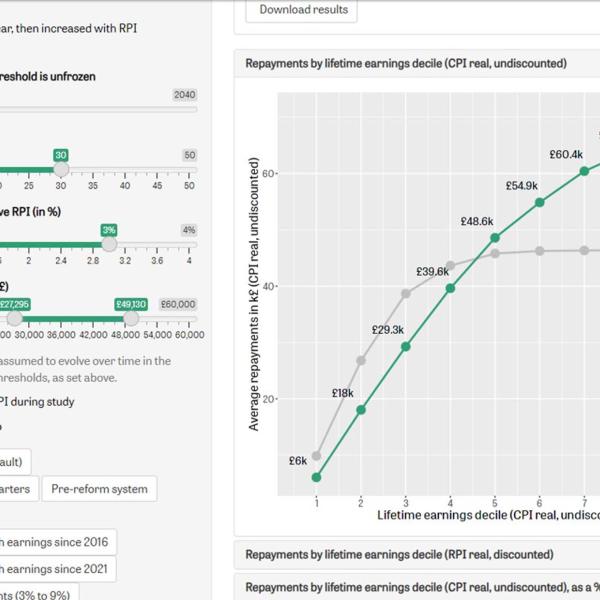

For those who started university between 2012 and 2022, their loans normally accrue interest at a rate between the rate of RPI inflation and RPI inflation plus 3%, depending on a graduate’s income (the interest rate is capped at the ‘prevailing market rate’, which is based on market interest rates for unsecured consumer credit). Any outstanding loan is written off after 30 years. Amongst the 2022 university entry cohort, we expect graduates in the lowest 10% of lifetime earnings to pay back around £6,000 on average towards their student loans, because they will rarely earn above the repayment threshold. At the other end of the scale, average student loan repayments of the highest-earning 30% of graduates are likely to be more than £60,000. They can expect to pay back more than they borrowed because of interest accrued on their loans.

The strong link between repayments and lifetime earnings for the 2022 entry cohort is illustrated in Figure 1. This picture looks somewhat different when repayments are considered as a percentage of average lifetime earnings. The lowest-earning 10% of graduates repay around 1% of their lifetime earnings, while the highest-earning 10% of graduates repay around 1.3% of their lifetime earnings. Those in the middle of the graduate earnings distribution repay the most at around 2.4% of their lifetime earnings. Overall, we expect around half of the 2022 entry cohort not to clear their loans by the end of the repayment period.