Summary

The government is quietly tightening the financial screws on students, graduates and universities. Students will see substantial cuts to the value of their maintenance loans, as parental earnings thresholds will stay frozen in cash terms and the uplift in the level of loans will fall far short of inflation. This continues a long-run decline in the value of maintenance entitlements. The threshold below which students are entitled to full maintenance loans has been unchanged in cash terms at £25,000 since 2008; had it risen with average earnings, it would now be around £34,000.

Separately, the student loan repayment threshold will also be frozen in cash terms. This is effectively a tax rise on middle-earning graduates. A graduate earning £30,000 will need to pay £113 more towards their student loan in the next tax year than the government had previously said. Finally, tuition fees will remain frozen in cash terms for another year, which hits universities and mainly benefits the taxpayer. On the whole, as our updated student finance calculator shows, the government is saving £2.3 billion on student loans under the cover of high inflation.

Maintenance loans not maintained

Three weeks ago, the government quietly published the parameters of the maintenance loan system for the 2022–23 academic year. Two things stand out. First, parental earnings thresholds have remained frozen in cash terms. Second, the rate at which the level of maintenance loans will be increased – 2.3% – falls far short of both the current level of inflation and the level of inflation that can reasonably be expected over the next year. This means that many students will see their maintenance loans cut in real terms, even though the real value of their parents’ incomes will also have fallen. In combination, these real-terms cuts will save the taxpayer around £700 million per cohort compared with policies that would have roughly preserved the 2020–21 level of support (uprating the parental earnings thresholds with average earnings growth and uprating loan amounts with expected RPIX inflation).[1]

The freeze in the parental earnings thresholds is not a new policy. The lower income threshold has been frozen at £25,000 since 2008. If a student’s parents together earn less than that threshold after deductions for pension contributions and other children, the student is eligible for the full maintenance loan, which will usually be £9,706 (except if they study in London or live with their parents). If the parental earnings threshold had been indexed to average earnings, it would now be around £34,000 and roughly twice as many students would be eligible for the full maintenance loan. Because of the threshold freeze, a student whose parents earn £34,000 after deductions – still well below what two parents working full-time and receiving the National Living Wage would earn – will now only be eligible for a maintenance loan of £8,456. If the threshold had been indexed to average earnings, they would be eligible for the full amount, or about £100 more each month.

The higher income threshold, above which students are only eligible for the minimum level of maintenance loans (usually £4,523), has also been frozen since 2016 at around £62,300. These threshold freezes mean that every year, maintenance loan entitlements for students with middle-earning parents have fallen. The effect will be especially strong for the 2022–23 academic year, because earnings have been rising fast in cash terms (but not in real terms).

Adding to the squeeze is this year’s low rate of increase in maintenance loan levels of just 2.3%. This was determined by a forecast for RPIX inflation between the first quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023, which in principle is reasonable. But the forecast was taken from the November 2020 OBR projections, which by now are woefully out of date. A week after the government first published the rate of maintenance loan increase in October 2021, the OBR already projected 3.7% RPIX inflation (and 5.6% for the current academic year, when the increase was 3.1%). Since then, inflation has further surprised on the upside. Last Thursday’s inflation forecast from the Bank of England suggests that if maintenance loans for the 2022–23 academic year were to reflect actual RPIX inflation over the two years to the first quarter of 2023, they would need to be more than 7% higher than they will in fact be. Put differently, a student getting a full maintenance loan will be £60 worse off each month than if the OBR’s original forecast had been correct.

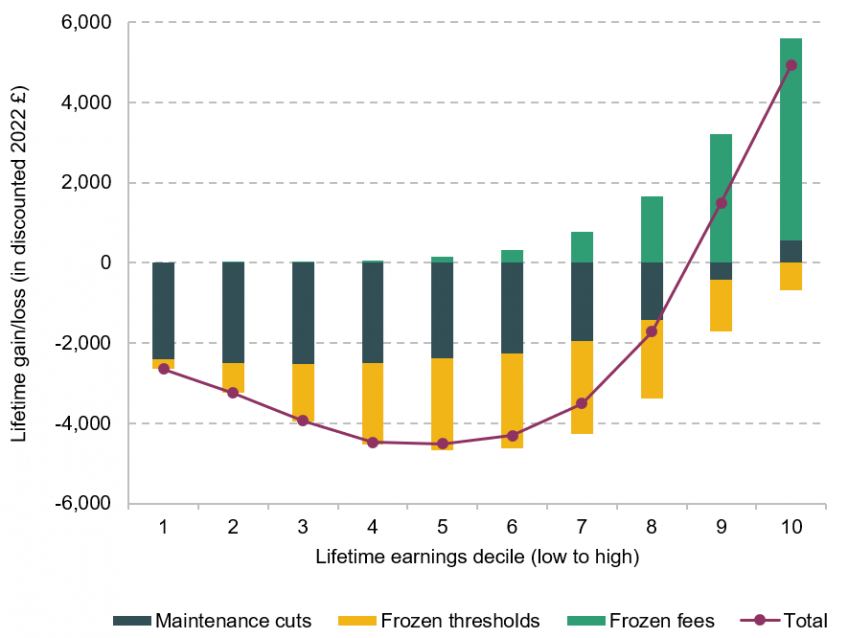

This amounts to a substantial real cut in maintenance loan levels between the 2020–21 and 2022–23 academic years, on top of cuts in entitlements as a result of the continuing freeze in the parental earnings thresholds. These maintenance cuts will have a similar impact on lifetime earnings to the recently announced threshold freeze, but they hit lower-earning students more (see Figure 1) and will hit them while they are studying, when many are on very tight budgets. The Chancellor’s support measures announced last week will do little to cushion the blow, as students are generally exempt from council tax (so won’t benefit from the discount) and often live in large households while studying (so the £200 energy ‘loan’ will amount to little per student now, but if they split up into separate households later, students might end up ‘repaying’ much more than they ‘borrowed’). These cuts seem unlikely to be deliberate government policy, but that does not make them less damaging. They are likely to cause genuine hardship for students from poorer families.

Figure 1. Impact on student loan borrowers by lifetime earnings decile (2022 entrants)

Note: Following standard Department for Education practice, all earnings and outlays are inflation-adjusted using RPI, lifetime earnings are discounted at a rate of 0.7% and loan outlays are not discounted. In contrast to the latest Department for Education forecast, our model accounts for RPI reform. ‘Maintenance cuts’ assumes that thresholds would otherwise have been uprated with average regular weekly earnings between Q1 2019 and Q1 2021 (7.4%), and amounts would have been uprated with expected RPIX inflation between Q1 2021 and Q1 2023. Expected RPIX inflation is the median projection for CPI inflation based on market interest rate expectations from the Bank of England’s February 2022 Monetary Policy Report, plus the expected difference between RPIX and CPI inflation from the OBR’s October 2021 economic projections; this comes to 7.0% for Q1 2021 to Q1 2022 and 5.9% for Q1 2022 to Q1 2023. ‘Frozen thresholds’ assumes that graduate earnings thresholds would otherwise have been uprated by the rate of increase in average regular weekly earnings between Q1 2020 and Q1 2021 (4.6%) and will go back to being uprated by average weekly earnings from 2023–24. ‘Frozen fees’ assumes that maximum fees would have been uprated by expected RPIX inflation between Q1 2021 and Q1 2023, calculated as set out above.

Source: Author’s calculations using IFS student finance calculator.

Threshold indexing thrown out

The government has recently announced that the student loan repayment threshold – the earnings level above which graduates need to make repayments on their student loans – will be frozen at £27,295 instead of being raised by 4.6% to £28,550 in line with previous policy. The two interest rate thresholds, which govern what interest rates are charged on student loans, were also frozen in nominal terms. According to the previous regulations that were in place since 2018, all three thresholds were indexed to the rate of growth in average regular earnings.

As we pointed out, this effectively constitutes a tax rise for middle-earning graduates (Figure 1), which will lower the taxpayer cost of student loans by around £600 million per cohort if kept in place for one year. Any graduate with an outstanding student loan earning above £28,550 will need to pay an extra £113 towards their loan in the next tax year compared with what they otherwise would have paid, and – even if the threshold is frozen for only one year – more in every subsequent tax year. This will add up to an average lifetime loss of more than £2,000 in discounted present-value terms for middle-earning graduates, as they will pay off a larger portion of their student loans. Graduates in the bottom 10% of lifetime earnings will be largely unaffected by the freeze, as they typically do not earn enough to reach the threshold. Those in the top 10% of lifetime earnings will mostly pay off their loans either way, so higher repayments earlier in life just mean that they pay off their loans more quickly.

We have been here before. In 2017, the government also froze the repayment threshold at £21,000 instead of uprating it in line with average earnings as had previously been planned. The freeze was originally meant to go on until 2021, but this proved so unpopular that in a large giveaway to graduates, Theresa May’s government more than reversed the impact of the freeze by increasing the threshold to £25,000 in 2018 and indexed the threshold to average earnings again. This year’s renewed freeze might be read as an admission that this was a mistake. At current projections, it would take another three years of freeze to get the threshold back to where it would have been had it been increased with average earnings all along.

Whatever else one may think of the threshold freeze, it does seem somewhat at odds with the government’s insistence that students are ‘consumers’ who should demand that universities deliver on their promises. Clearly the government does not think the same applies to student loan borrowers, who might have relied on the government’s 2018 commitment to index the repayment threshold to average earnings when taking out their loans. Importantly, no private lender would be allowed to change loan conditions retrospectively like this. However, even with the threshold freeze, government student loans remain highly subsidised and offer a much better deal for most graduates than any private lender would be willing to offer.

What will really matter in the long term is how long this threshold freeze stays in place. The figures above assume that the threshold will only be frozen for one year, and after that it will be indexed to average earnings again. But just as keeping maximum tuition fees frozen has become a convenient way of cutting government expenditure on higher education, extending the threshold freeze for another year may become a politically expedient way to raise more money from graduates. According to the October 2021 OBR forecast, a five-year freeze until 2026–27 would lower the repayment threshold to around £24,500 in today’s money. This, alongside freezes in the interest rate thresholds, would lower the long-run taxpayer cost of loans by another £1.3 billion. Again, it is middle-earning graduates who would have to pick up the slack.

Fee levels falling

Finally, 2022–23 will be the fifth year that maximum tuition fees have been frozen in cash terms at £9,250; they have largely been unchanged in cash terms since 2012, when they were £9,000. This already amounts to a 15% real-terms cut in the level of tuition fees over the past decade. The continuing freeze means there will be further large cuts in real terms this academic year and next, given the high rate of inflation. If maximum fees were to be increased with projected RPIX inflation from the 2020–21 level, they would need to be nearly £10,500 in 2022–23.

The government’s stated goal with this freeze is to ‘reduce the burden of debt on students’ and ‘make higher education more affordable’. But this is at best one-third true. Only a quarter of student loan borrowers can expect to pay back their loans; real cuts in fees only help those high-earning borrowers and the small share of students (or their parents) who are eligible for loans but do not take them up (see Figure 1). In fact, the main beneficiary of real cuts in fees is the taxpayer, who will benefit to the tune of £1 billion per cohort from the freeze in maximum fees between 2020–21 and 2022–23 alone.

[1] Expected RPIX inflation is the median projection for CPI inflation based on market interest rate expectations from the Bank of England’s February 2022 Monetary Policy Report, plus the expected difference between RPIX and CPI inflation from the OBR’s October 2021 economic projections; this comes to 7.0% for Q1 2021 to Q1 2022 and 5.9% for Q1 2022 to Q1 2023.