MPs will debate a number of petitions today relating to university tuition fees. These petitions are asking for all or part of tuition fees relating to the 2019/20 and/or 2020/21 academic year to be reimbursed. Between them, they have gathered nearly a million signatures.

The petitioners point out that the university strikes and now the COVID-19 outbreak have disrupted university education in such a way that students did not have the university experience they had signed up for. They argue that as a consequence, students should be entitled to a reimbursement on their fees. While not all of the petitions are explicit on who should pay whom, the general presumption seems to be that it would be universities paying back whoever paid them in the first place (so the government-owned Student Loans Company in most cases).

The total cost to universities of refunding fees in this way for a whole year would be around £10 billion if the policy applied only to full-time undergraduates domiciled in England. Including all fee-paying students – which includes students from other home nations, international students, part-time students, and those studying for other degrees – would nearly double the amount to be reimbursed. This compares to total university income of £41 billion in 2018/19. A less radical policy of reimbursing just the most-disrupted third term of the 2019/20 academic year would cost universities a third of those figures.

Among undergraduate students domiciled in England, this kind of reimbursement of tuition fees would primarily benefit the small minority of students who pay their tuition fees out-of-pocket, and those who go on to have high earnings after they have graduated. Only the roughly 10% of students (or their parents) who pay tuition fees directly would receive any immediate pay-out. All others will have taken out the full government-backed loan to cover their fees, so reimbursement would merely lower their student loan balance.

This change to the student loan balance only matters for high-earning graduates. The reason is that mandatory repayments only depend on graduates’ earnings, and all remaining student loan balances are written off 30 years after graduates start repaying. Lower-earning graduates will not repay their loans within 30 years whether or not tuition fees are reimbursed, so their repayments would be the same.

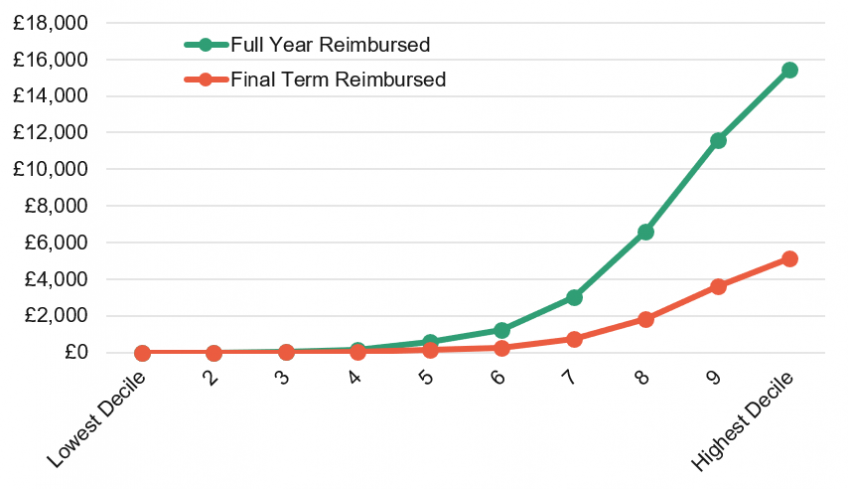

Figure 1. Reduction in repayments by graduate earnings decile for full-time undergraduates domiciled in England

Notes: Calculations using the IFS graduate earnings model. All amounts are undiscounted and in 2020 prices.

The following calculations consider the effect of the policy suggested by the most popular petition — which proposed refunding fees for the whole of the 2019/20 academic year — as well as the effect of refunding fees only for a third of that academic year as suggested by a different petition. In each case, the policy is assumed to apply to full-time undergraduate students domiciled in England only.

Figure 1 shows the average benefit for borrowers who entered university in 2019 by lifetime earnings decile. Borrowers in the bottom half of the graduate earnings distribution would gain virtually nothing from tuition fee reimbursement, be it for a third of a year or a whole year. At the other end of the spectrum, the highest-earning 10% of borrowers actually save substantially more from the policy than they would have been charged in tuition fees (a saving of more than £15,000 compared to typical tuition fees of £9,250), because they would have accrued a substantial amount of interest.

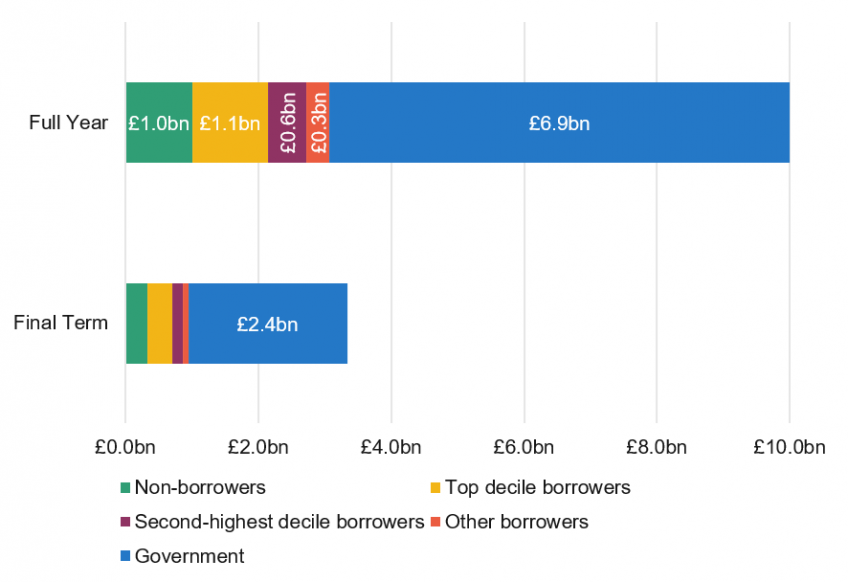

Figure 2. Distribution of gains from tuition fee reimbursement for full-time undergraduates domiciled in England

Notes: Calculations using the IFS graduate earnings model. All amounts are in 2020 prices. Future receipts are discounted using a real discount rate of 0.7%. Non-borrowers denote those who do not take out a student loan to pay their tuition fees, and instead pay out pocket. Top decile borrowers denote those who take out a student loan and are subsequently in the top 10% of earners who did so. Second-highest decile borrowers denote those who take out a student loan and are subsequently in the top 20% but not in the top 10% of earners who did so.

The corollary of this is that by far the largest direct beneficiary of any such reimbursement by universities would be the government. This is illustrated in Figure 2. Of the total amount reimbursed, more than two thirds would end up in the government’s coffers. The reason is that the lower student loan balances resulting from any reimbursement would reduce the amount of unrepaid student loans the government would need to write off. The share of reimbursements accruing to the government would be slightly higher if only a third of a year’s fees were reimbursed, as even fewer student loan borrowers would be affected.

These projections are based on a number of assumptions about the time students spend at university, graduate earnings, and the future student loan system, which will not hold precisely. The most important risk to our projections is the graduate earnings forecast, which follows the central scenario of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s July 2020 Fiscal Sustainability Report. If graduate earnings should turn out to be lower (higher) than forecast, a bigger (smaller) share of reimbursements would go to the government, and less (more) would benefit student loan borrowers.

Should the government pick up the tab?

Even if the government did compel universities to reimburse students, it should be mindful of the impact on universities’ finances. As university finances are already under strain, primarily due to the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the main university pension scheme, a number of universities may become insolvent if they were required to shoulder the losses from tuition fee reimbursements as well. While tuition fees from domestic undergraduates make up only about a quarter of income for the university sector as a whole, several institutions get more than two thirds of their income from domestic undergraduate fees, and reliance on domestic undergraduate fees tends to be high for the least selective institutions, which prior to the pandemic also tended to have the weakest finances.

In order to avoid the disruption caused by university bankruptcies, the government could cover some or all of the cost of reimbursement. As most of the benefits of reimbursement would accrue to the government, most of the cost to universities would be covered if the government merely passed back its own gains. If the government funded the whole cost of reimbursing undergraduates domiciled in England, the long-run cost to the taxpayer would be £3.1 billion for a full year and £1 billion for reimbursement of one term’s fees.

The Problem with Postgrads

The same logic does not apply to potential reimbursements of postgraduates, as most of these students (or, for example, their parents) pay out of pocket rather than through government loans. Furthermore, we expect most of the small minority who do get government postgraduate loans to pay them back in full. As a result, only a negligible share of any reimbursements would accrue to the government. The same applies to international students.

There is also no cap on these students’ fees, which for some high-cost degrees such as MBAs exceed £30,000 per year. As a result, were these fees to be reimbursed by universities, and were the government to decide to help universities meet this cost, then the cost for the government of covering postgraduate and international student fees would be much larger than paying for England-domiciled undergraduate fees, even though the number of postgraduate and international students is much smaller.

No good options for the government

No reimbursement option is particularly palatable for the government. Forcing universities to reimburse students may well bankrupt some of them, causing major disruption for some students and others. If the government shouldered the full costs, that would constitute an expensive give-away benefitting mainly high earners and international students. That cost could be much reduced by limiting any reimbursements to undergraduates domiciled in England, but that would likely raise accusations of unfairness.

An entirely different approach would be to pay all students the same amount directly rather than refunding tuition fees. While that would be more of a compensation payment rather than a reimbursement, it would seem appropriate that all students should benefit by the same amount, as all will have missed out on the university experience by roughly the same measure.

A different question is whether that kind of compensation payment would be fair. Graduates earn a lot more than non-graduates on average, and often have wealthier parents. Arguably, students also suffered much less from the effects of the crisis on average than their peers who did not go to university, many of whom will have struggled to find a job or have been laid off.

On the whole, there does not seem to be a compelling case for blanket fee refunds or compensation payments. It is therefore no wonder that the government has so far shown no willingness to get behind any of the options.