Funded by the Nuffield Foundation

This continues a long historical pattern where further education receives the smallest increases when overall spending rises and the largest cuts when governments are looking to reduce spending. The current government has sought to make technical education a priority and provided additional funding in the 2019 and 2020 spending rounds and the 2021 Spending Review. However, this has not been enough to reverse the real-terms cuts experienced by providers after 2010.

Spending per student over time

Colleges and sixth forms are currently facing three main challenges. First, like all education providers, they face rising costs, both in terms of staff salaries and non-staff costs. Second, student numbers are rising as a result of a population boom moving through the education system. However, an apparent drop-off in participation rates (particularly amongst 18-year-olds) is leading to smaller increases than previously expected, which is creating uncertainty in the short term. Third, the government is pressing ahead with an overhaul of the post-16 qualification landscape. In the short run, this includes the removal of funding from Level 3 qualifications that cover the same areas as the government’s new ‘T levels’. In the longer run, the government has set out plans for yet another major reform of post-16 qualifications, with academic and technical qualifications combined into a new ‘Advanced British Standard’ (despite the fact that education is devolved).

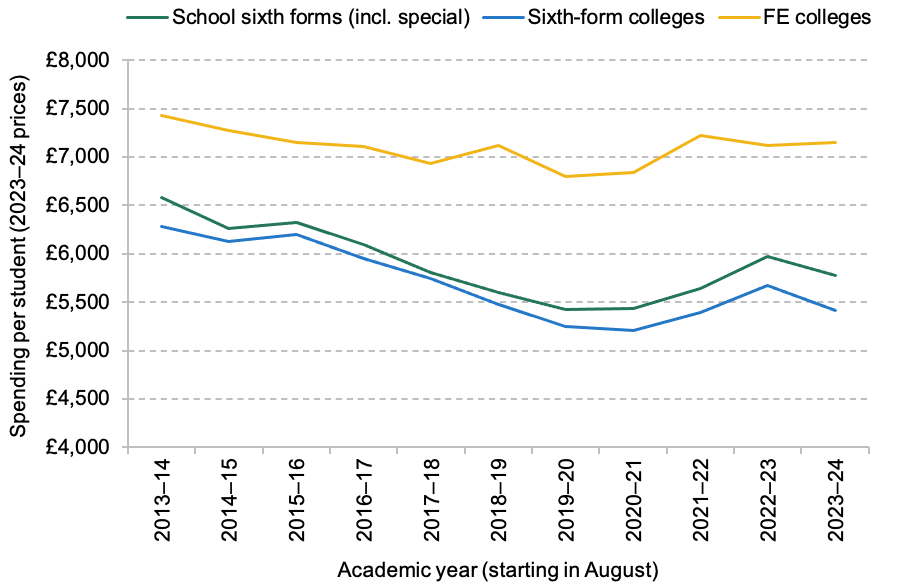

Figure 1 shows spending per student aged 16–18 in school sixth forms, further education (FE) colleges and sixth-form colleges in each academic year from 2013–14 onwards (the earliest year covered by the allocations data). In this graph and the remaining analysis in this section, we consider funding allocated per student aged 16–18, as opposed to actual amounts of spending on individual students, which could be higher or lower depending on how schools and colleges spend money on different stages of education.

Figure 1 - Spending per student in further education colleges (16–18), sixth-form colleges and school sixth forms

Note and source: See Methods and data. HM Treasury, GDP deflators, November 2023.

In each year, spending per student aged 16–18 is noticeably higher in FE colleges. In the 2023–24 academic year, FE colleges are projected to spend roughly £7,100 per pupil, compared with £5,800 in school sixth forms and £5,400 in sixth-form colleges. This is because students in FE colleges are more likely to study vocational qualifications and are more likely to come from deprived backgrounds, both of which attract higher levels of funding.

Real-terms cuts between 2013–14 and 2019–20 were similar across school sixth forms and sixth-form colleges, at 16–18%. The cuts for FE colleges were smaller, at 8% over the same period. This partly reflects the fact that FE colleges have a higher proportion of vocational qualifications, which have received more from new funding streams such as the Capacity and Delivery Fund (CDF). Additionally, there has been a decline in part-time study in FE colleges. The proportion of part-time 16- to 18-year-old students in FE colleges decreased from 17% in 2013 to 10% by the end of the decade, which has led to an increase in funding per student.

In the 2019 and 2020 spending rounds, the government allocated an additional £700 million in funding for colleges and sixth forms up to 2021–22, and then a further £1.6 billion up to 2024–25 in the 2021 Spending Review. This makes for a total of £2.3 billion in additional funding by 2024–25 relative to 2019–20 (all in cash terms). In the current academic year (2023–24), spending per pupil is set to have risen by 5% in FE colleges, 3% in sixth-form colleges and 6% in school sixth forms relative to 2019–20 in real terms. In the case of FE colleges, this takes spending per student back to about 2015/2016 levels, but spending per student in school sixth forms and sixth-form colleges remains well below these levels.

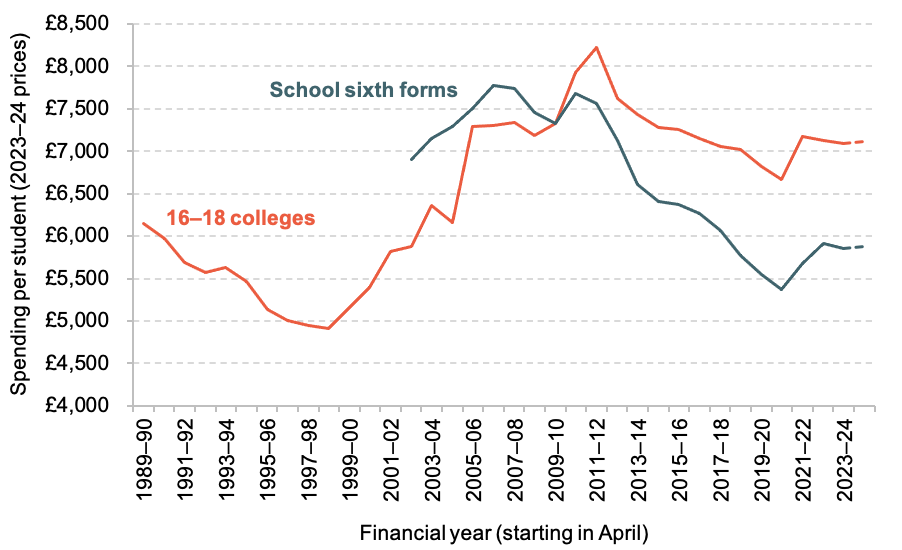

This is further illustrated by Figure 2, which shows how per-student spending levels in school sixth forms and colleges have evolved between 1989–90 (2002–03 for school sixth forms) and the present day, and how the additional funding will change spending levels up until 2024–25. For data reasons, we combine FE and sixth-form colleges, which we refer to as 16–18 colleges, and track spending by financial instead of academic year.

Figure 2 - Spending per student in 16–18 colleges and sixth forms

Note and source: See Methods and data. HM Treasury, GDP deflators, November 2023.

Since 2010–11 (when public spending cuts began to take effect), there has been a decline in per-student spending across all types of institutions. Between 2010–11 and 2019–20, spending per student fell by 14% in colleges and 28% in school sixth forms. For colleges, this left spending per student at around its level in 2004–05, while spending per student in sixth forms was lower than at any point since at least 2002.

Overall, per-student spending in 16–18 education is set to rise by 3.5% in real terms between 2021–22 and 2024–25. Yet even with the additional funding set out in recent spending reviews, college spending, which includes spending on both sixth-form colleges and FE colleges, will still be around 10% lower per student in 2024–25 than in 2010–11, while school sixth-form spending per sixth-form student will be 23% below 2010–11 levels. Therefore, the additional funding for sixth forms and colleges will only partially reverse the cuts of the previous decade. By 2024–25, current forecasts imply that about a quarter of the cuts for colleges between 2010–11 and 2019–20 will have been reversed, and even less for school sixth forms.

Uncertainty on costs and student numbers

In common with the rest of the education sector, colleges and sixth forms are facing rising costs for inputs such as staff and energy. The number of 16- to 18-year-olds is also expected to rise rapidly, with projections from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) implying a 14%, or more than 250,000, rise in the number of 16- to 18-year-olds between 2019 and 2024. In reality, student numbers have not risen by as much as this. Uncertainty on costs and on student numbers are also interacting in quite important ways.

On staffing costs, college staff have seen significant real-terms pay cuts since 2010. The recommended pay of college teachers declined by 18% in real terms between 2010–11 and 2022–23, based on trends in CPIH inflation (CPIH is the Consumer Prices Index including owner-occupiers’ housing costs). Over the same period, teacher pay scales fell by between 5% and 13%. There have been especially sharp declines in recent years due to high levels of inflation. A large part of the reason for these real-terms salary falls is the squeeze on college budgets over the last decade, which has limited the ability to offer higher pay rises. The net result is that college teacher pay was, on average, about £7,000 or 21% lower than school teacher pay in 2022–23. This is likely to be connected to the higher share of college teachers that leave their job in each year (16%) as compared with school teachers (10%).

For 2023–24, the Association of Colleges (AoC) has recommended pay rises of 6.5% for college staff. This is the highest recommended pay rise for college staff for at least 15 years, and is in line with recommendations for school teachers this year. Schools received additional funding of £900 million over a full year to help fund the additional costs of the 6.5% pay award. At the same time (July 2023), the government announced an ‘additional’ £185 million in 2023–24 and £285 million in 2024–25 to help colleges afford a similar pay rise. This was implemented by increasing 16–19 funding rates for the 2023–24 academic year more than had been expected. This included a 4.6% increase in the main baseline funding rates, a 30% increase in the uplift provided by each of the programme cost weightings for higher-cost subjects, as well as some specific increases for particular subjects, and an extra £20 million in funding for disadvantage. Since then, in October, the Prime Minister has also announced a further £150 million per year to increase funding for pupils retaking English and maths in 16–19 education and apprenticeships (Department for Education, 2023). This is part of ambitions for a new ‘Advanced British Standard’ (see below for further discussion).

In reality, this extra funding is being recycled from within the additional £1.6 billion announced at the time of the 2021 Spending Review. Actual student numbers have turned out to be lower than expected at the time of the Spending Review, which has allowed the government to increase funding rates by more than it expected. In this sense, the money announced in July and October 2023 was not, strictly speaking, additional and it is already included within our analysis of spending per student above.

Considering overall costs and funding for colleges in 2023–24, staff pay is expected to rise by 6.5% if colleges follow AoC recommendations. Initial evidence suggests that most colleges are implementing pay rises of 6.5–7.5%, and CPI inflation is expected to be about 6% for 2023–24. Cash-terms funding per student in FE colleges (calculated for Figure 1 above) is expected to grow by 6.4% in 2023–24. This would suggest cost rises are probably just about affordable for colleges, on average. Furthermore, our calculations for funding per student in 2023–24 make use of ONS projections showing a 3.0% rise in the number of 16- to 18-year-olds in 2023. The rise in the number of that age group in education may turn out to be lower than this, with the funding rise being spread over a smaller population.

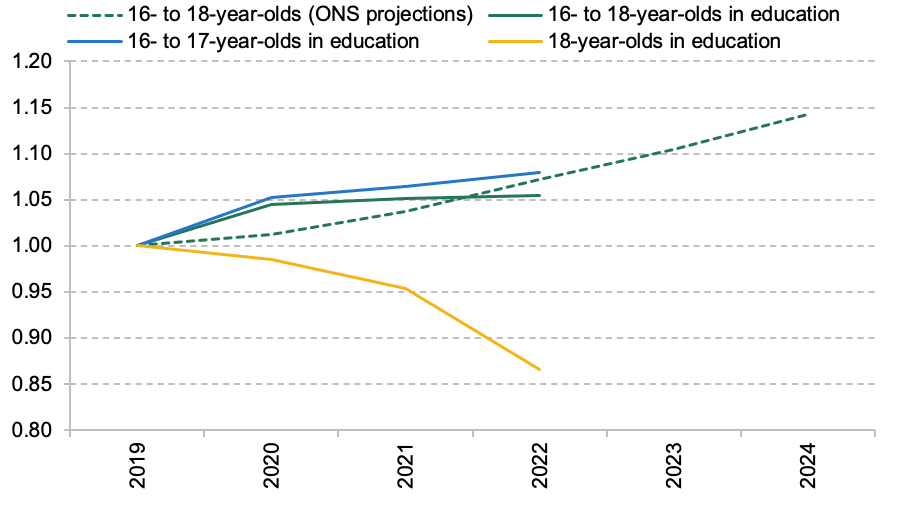

To better understand the implications of the uncertainty on student numbers, Figure 3 shows the number of 16- to 18-year-olds in education over time (indexed to 2019) together with ONS projections for the total number of 16- to 18-year-olds. We also break down the figures in education into those aged 16–17 and those aged 18. We exclude 18-year-olds attending higher education (HE), in order to focus on the implications for colleges and sixth forms.

Figure 3 - Trends and projections in numbers of 16- to 18-year-olds over time, relative to 2019–20

Source: Department for Education, Participation in education, training and employment age 16 to 18; Office for National Statistics, 2020-based interim national population projections.

According to ONS projections, the number of 16- to 18-year-olds is expected to grow by 14% between 2019 and 2024, or a steady average of about 3% per year. The actual number of 16- and 17-year-olds in education initially grew much faster than ONS projections in 2020, reflecting increased education participation during the COVID-19 pandemic and poor labour market options. Since then, the number of 16- to 18-year-olds in education has been largely flat. Whilst ONS projections imply 7.2% growth in the number of 16- to 18-year-olds between 2019 and 2022, actual numbers in education have grown by the lower amount of 5.5%. Interestingly, Figure 3 also shows that the number of 16- and 17-year-olds in education has continued to grow, by a total of 8.0% or 80,000 between 2019 and 2022. In contrast, the number of 18-year-olds in education (excluding HE) has fallen by 13% or 20,000 between 2019 and 2022, with most of the fall happening in 2022.

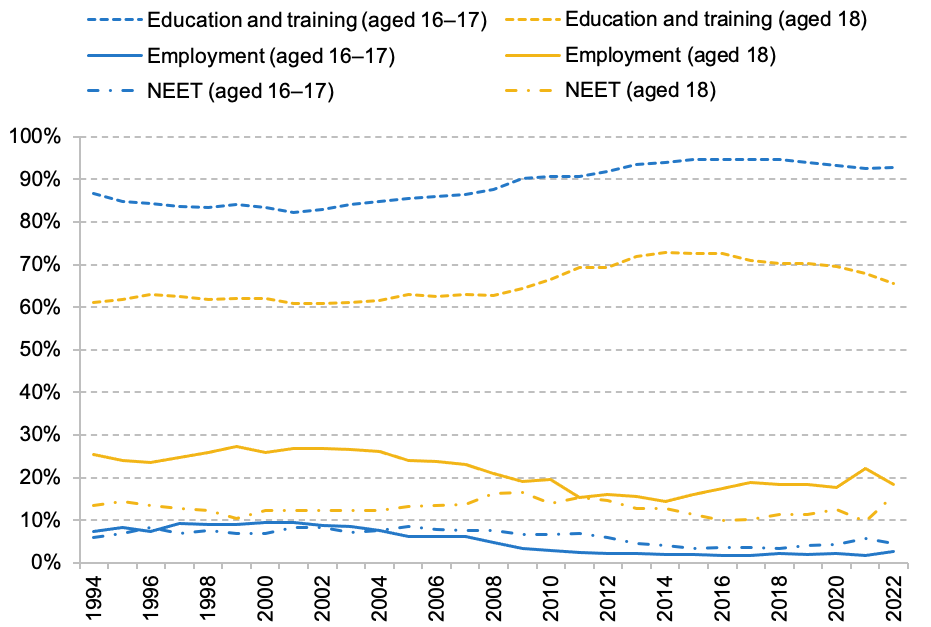

Figure 4 digs deeper into these trends by showing the shares of people aged 16–17 and of 18-year-olds in education or training, in employment, and who are classed as ‘NEET’ (not in education, employment or training) over time. To provide a complete a picture, this does include 18-year-olds in HE. The long-run trend is a rising share of young people in education and training between the late 1990s and mid 2010s, peaking around 2016 at about 95% for 16- and 17-year-olds and 73% for 18-year-olds. Since then, education and training participation has dropped off very slightly to about 93% for 16- and 17-year-olds in 2022. More dramatically, it has fallen to about 66% for 18-year-olds, the lowest level since 2010, with a drop of 4 percentage points since 2020 alone. This appears to have been made up for by a slight and gradual rise in the share of 18-year-olds in employment. It also reflects a sharp decline in the number of young people taking apprenticeships. Since peaking in 2015/2016, the number of apprentices under the age of 19 –predominantly 18-year-olds – has declined by 35%. More recently, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of 18-year-olds classed as NEET; 16% of 18-year-olds were NEET in 2022, near equal to the share last seen in the Great Recession of the late 2000s.

Figure 4 - Education participation and labour market status of people aged 16–17 and of 18-year-olds

Source: Department for Education, Participation in education, training and employment age 16 to 18.

The lower-than-expected growth in the number of 16- to 18-year-olds in education is the main reason that the government could increase funding rates for 2023–24 by more than expected. If this lower growth in student numbers continues into next year, then spending per student will likely be higher than our projections in Figure 2. This is clearly a source of uncertainty, and the fact that participation in education and training is dropping amongst 18-year-olds is a concern in itself.

Qualifications reform

An additional challenge faced by the sector comes from an overhaul of the post-16 qualification landscape. There is a major ongoing reform of Level 3 qualifications, with funding being removed from technical qualifications that overlap with T levels. In March 2023, the government published the final list of qualifications that will have their funding withdrawn from August 2024, which amounts to 134 qualifications.

The qualifications listed include many common BTEC and City & Guilds qualifications in subject areas that overlap with T levels. The removal of funding is estimated to affect around 40,000 enrolments by 16- to 19-year-olds, which equates to 2% of all enrolments at Level 3 and 6% of non-A-level enrolments at Level 3. These reforms are especially likely to affect the post-16 choices of poor households (eligible for free school meals), students with special educational needs, and low attainers who are not yet ready for T levels. It is vital that schools and colleges ensure that these students continue to have opportunities to access quality routes through post-16 education.

Reforms to further education qualifications are set to continue into the future, with the government recently announcing its intention to introduce the ‘Advanced British Standard’ (ABS). The proposed ABS would be a new baccalaureate-style qualification for 16- to 18-year-olds that would eventually replace A levels and T levels. Under the ABS, students would normally study at least five subjects and would spend significantly more time in the classroom, with a minimum of 1,475 hours of teaching over two years. Currently, a typical post-16 student receives up to 1,280 hours of tuition over two years of study. The government’s commitment that every student will study some form of maths and English up to the age of 18 will also be part of the ABS.

The ABS is a long-term policy goal, which the government has said will take a decade to fully implement. On the surface, the move to a broader post-16 curriculum with an increase in teaching time is a positive step. Indeed, England stands out from other countries in the narrowness of its post-16 education curriculum and providing students with the opportunity to drop maths after 16. However, the advantage of this move must be balanced against the risk of adding further policy churn to the post-16 qualification landscape, especially given that T levels are still to be fully rolled out. Practically, the additional teaching under the ABS would also require higher levels of funding and the recruitment of additional further education teachers.