Explore how different reforms would affect student loans using our interactive tool >>>

The student finance system in England is both unpopular among students and expensive for the taxpayer. Reform now seems all but inevitable. Given the pressures on the public finances from COVID-19, the Chancellor may want to see graduates themselves bearing a higher proportion of the cost. We have constructed a new student finance calculator, based on our detailed analysis of graduate earnings and the student finance system, which allows users to look at the effects of changing any parameter of the system. It shows that it is essentially impossible for the Chancellor to save money without hitting graduates with average earnings more than those with the highest earnings.

Reform is overdue

Students may fear they will bear the costs of their degrees, but the taxpayer will actually bear nearly half on average. At a long-run taxpayer cost of around £10 billion per cohort, the current student finance system for undergraduate degrees is expensive for the public finances. Most of that cost, or around £9 billion, reflects the government cost of student loans, as around 80% of students will likely never pay back their loans in full. For the 2021 cohort of university starters, our modelling suggests that 44% of the value of student loans will in the end be paid by the taxpayer.

Besides its high cost, the current system has also been widely criticised on other grounds. The interest charged on student loans now far exceeds the government’s cost of borrowing, so the government is making large profits from lending to high-earning graduates who took out student loans (while their peers who financed their education in other ways are off the hook). The system also gives universities a free pass to admit as many students as they like for any course, leaving the government little control over spending.

These concerns mean that reform now seems very likely. Lord Adonis, one of the architects of the income-contingent student loan system in the UK, has described the current system as ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ and called for radical reform. Reports by the Lords Economic Affairs Committee and the Treasury Select Committee in 2018, as well as the Augar Review of Post-18 Education and Funding in 2019, came to similar conclusions.

No easy options for the Chancellor

Given the new pressures on the public finances from the COVID-19 crisis, as well as additional planned spending on adult education under the heading of the Lifelong Skills Guarantee, the Chancellor is likely to be keen to see graduates shouldering a larger share of the cost of their education. As the new IFS student finance calculator shows, this will be harder than it sounds within the current framework for student finance.

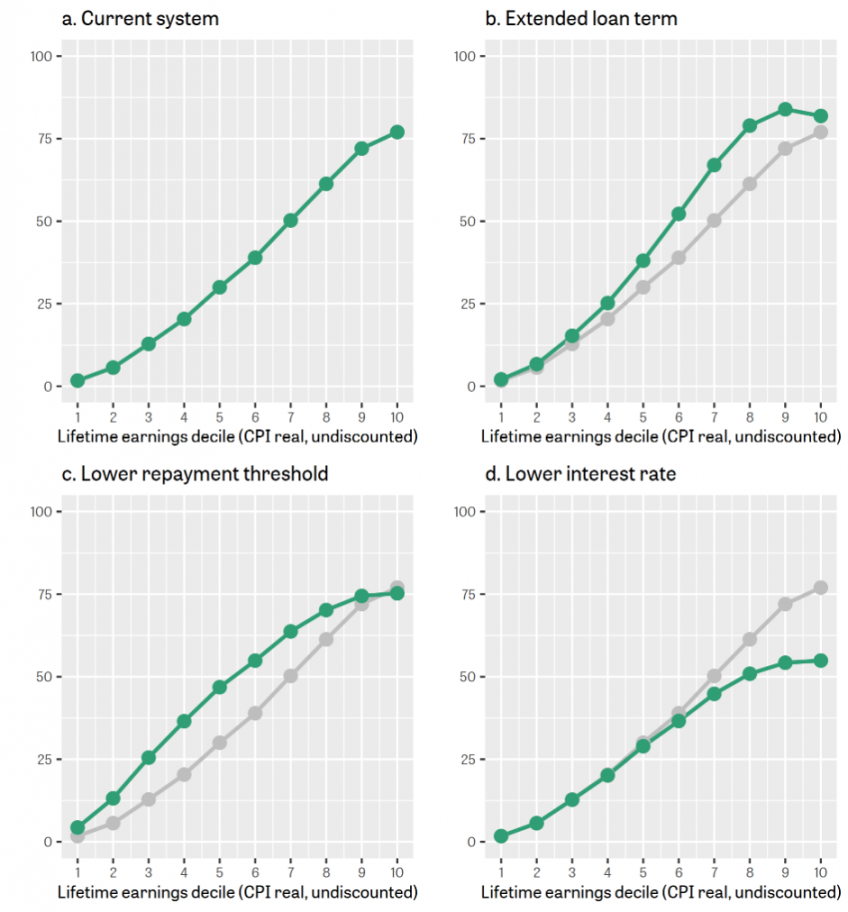

Despite its many flaws, the current system does have the desirable characteristic that it is progressive: the highest-earning borrowers repay by far the most towards their student loans, and lower-earning borrowers pay less (see Panel a of the figure below). Because the highest-earning borrowers already pay so much, any plausible way of raising more money from the system will shift costs onto borrowers with middling earnings but largely spare those with the highest earnings.

Increasing the repayment rate on student loans would be the most straightforward way to raise more money, but seems to be both politically unpalatable and economically misguided. Counting both employer and employee National Insurance contributions (NICs) and student loan repayments as taxes – which they effectively are for all but the highest-earning borrowers – graduate employees who are repaying their loans and earn above the loan repayment threshold (currently £27,295) will already pay half of any additional pound that goes towards their salary in tax once the new health and social care levy takes effect (counting tax as a share of labour cost, i.e. gross earnings plus employer NICs). That figure rises to 58% for those earning above the income tax higher-rate threshold (currently £50,270) and 64% for those who also have a government postgraduate loan.

Marginal tax rates in per cent of labour cost (gross earnings plus employer NICs)

Gross earnings | Non-graduates | Graduates | Graduates with postgraduate loans |

£27,000 | 42% | 42% | 47% |

£30,000 | 42% | 50% | 55% |

£51,000 | 51% | 58% | 64% |

Note: Figures for the 2022–23 tax year, assuming that the repayment rates on student loans stay unchanged and the repayment threshold remains between £27,000 and £30,000 per year.

A more realistic alternative on the table is to extend the loan term for student loans. At the moment, all outstanding student loans are written off 30 years after students start repaying, which generally happens in the year after they leave university. Many commentators, including the authors of the Augar Review, have suggested extending the loan term to 40 years.

While that would avoid increasing the tax burden on additional earnings for borrowers in the first 30 years of their working lives, the borrowers most affected by this change would still be those with high but not very high lifetime earnings (Panel b). The loan term matters little for those with the lowest lifetime earnings, as most of them will in any case not earn above the repayment threshold and thus not make extra repayments. It also does not affect the highest-earning borrowers much, as most of them will repay their full loans in fewer than 30 years.

Another option is to lower the repayment threshold for student loans, also recommended by the Augar Review (Panel c). Again, this would hit graduates with middling earnings most. The lowest-earning borrowers would be largely unaffected, as they would pay back little either way. Unless the thresholds for loan interest rates were changed at the same time, the highest-earning borrowers would even end up paying less, as they would pay off their loans more quickly and thus accumulate less interest.

Average repayments in CPI real k£ by lifetime earnings decile, current system and reform options

Note: Panel a shows estimates for the current system (2021 entry cohort). Panel b shows the effect of extending the loan term to 40 years. Panel c shows the effect of lowering the repayment threshold to £20,000 (holding the interest rate thresholds fixed). Panel d shows the effect of reducing the student loan interest rate to the rate of RPI inflation. In panels b to d, grey dots show the current system for comparison.

High interest rates mean some graduates pay back much more than they borrow

Finally, changes to the accounting treatment of student loans introduced in 2019 mean that the Chancellor may be keen to reduce the interest rates charged. Before the changes, any interest accrued on student loans was counted as a receipt in the government accounts, while write-offs were only counted as spending at the end of the loan term (or not at all if the loans were sold on). This meant that – conveniently for a Chancellor trying to balance the books – high interest rates on student loans substantially lowered the short-run budget deficit on paper, regardless of whether the loans would ever be repaid.

Under the new accounting treatment, the incentives for the Chancellor have reversed: high interest rates now actually increase the budget deficit in the short run. This is because only the share of student loans that the government expects to be paid back with interest is treated as a conventional loan; the rest is treated as spending in the year the loans are issued. The higher the interest rate, the lower the share of loans that will be paid back with interest, so the higher is the amount of immediate spending that counts toward the deficit. Lowering interest rates would still be a net negative for the public finances in the long run, as the interest accrued on the conventional loan share would be lower, outweighing the reduction in spending when loans are issued. But the Chancellor may be less concerned about the long run and more concerned about the next few years.

Lower interest rates would be a big giveaway to the highest-earning borrowers (Panel d) and would make the system substantially less progressive. Nevertheless, there is a strong case for lower rates independent of any accounting considerations. With current interest rates on student loans, many high-earning graduates end up paying back both much more than they borrowed and much more than it cost the government to lend to them. Students whose families can afford to pay the fees up front, and who are confident they will earn enough to pay back the loan, are worse off using the loan system. This erodes trust in the system, which should be a good deal for all graduates. Low- to average-earning borrowers are mostly unaffected in financial terms, as they typically do not clear their loans regardless of the interest rate, but even for them there may be undesirable psychological consequences to seeing their notional debt rising to ever higher levels because of the high interest charged.

Explore how different reforms would affect student loans using our interactive tool >>>

We are grateful to the Nuffield Foundation for funding this piece of work, which forms part of a wider programme looking at trends and challenges in education spending.

This research has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation (grant number EDO/FR-000022637), with co-funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) via the Impact Acceleration Account (ES/T50192X/1) and the Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy (ES/T014334/1).