For university students domiciled in England, government support for living costs takes the form of so-called maintenance loans. Each academic year, students are entitled to take out these maintenance loans on top of any loans for tuition fees. How much a student can borrow depends on their parents’ income, where they are studying (in London or elsewhere) and whether they live with their parents. This academic year, students from the poorest families studying outside London and not living with their parents are entitled to a maximum maintenance loan of £9,706.

Any amounts that students choose to borrow are added to their overall student loan balances and start accumulating interest. After leaving university, graduates have to make loan repayments from any earnings above a threshold (currently £27,295). Graduates stop making repayments either when they have paid off their loans, or once 30 years have elapsed since they became liable to make repayments.[1] Overall, this means there is a substantial government subsidy for student loans.

Under current policy, the real value of maintenance loan entitlements can normally be expected to rise slightly every year. This is because maintenance loans are adjusted with forecast RPIX inflation, which has a well-known upward bias compared with standard (CPI) inflation. However, there is no guarantee. If forecast RPIX inflation is less than actual inflation, the real value of maintenance loan entitlements will instead fall.

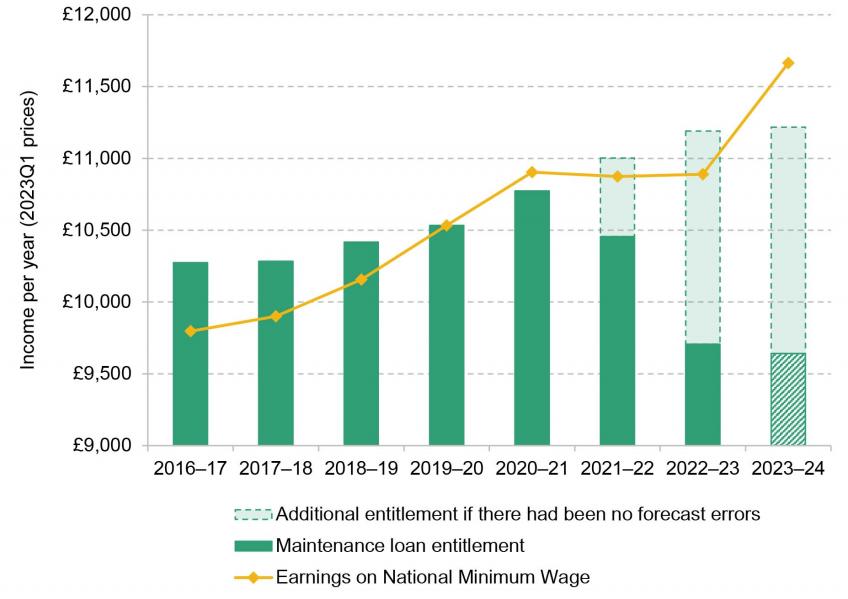

As we pointed out earlier this year, precisely that has been happening this year and last year. Merely because inflation has been higher than the OBR was previously expecting, the real value of maintenance entitlements has fallen substantially and is now at the lowest level it has been in seven years.[2] Compared with what they would have been entitled to in 2020–21, students from the poorest families have lost more than £1,000 in maintenance loan entitlement, which is around £250 more than we estimated back in June.

If forecasts had been accurate, maintenance loan entitlements would have kept rising over the last two years. Students from the poorest families studying outside London and living away from home would now be entitled to £11,190 in living cost support – around £1,500 more than they are actually receiving. Put differently, these students are £125 per month out of pocket merely because of errors in inflation forecasts.

Figure 1. Maximum maintenance loan entitlements and earnings for 30 weeks at the National Minimum Wage for a 21-year-old English student in real terms (2023Q1 prices)

Note: Axis is truncated. All monetary amounts are in CPI real terms. In order to align with government calculations, the price level for an academic year is taken to be the price level in the first calendar quarter falling into that academic year. Loan entitlement is for a student not living with their parents, studying outside London and entitled to the maximum support based on parents’ income. For minimum wage calculations, the academic year is taken to run from the start of October to the end of September, and the minimum wage at age 21 is used. Following the Augar Review, earnings on the minimum wage are calculated by multiplying the hourly minimum wage by the expected study time for a full-time undergraduate (37.5 hours per week over 30 weeks).

Source: House of Commons Library; Low Pay Commission recommendation; OBR’s November 2022 economic and fiscal outlook; authors’ calculations.

Importantly, these cuts in support will affect students not only this year but potentially for many years to come. There is no mechanism in place for these cuts ever to be undone, as past forecast errors are not considered when the adjustment in entitlements for the following year is determined. This means that – unless and until policy changes – any cuts will stay in place. Indeed, if the government continues to use out-of-date inflation forecasts for uprating, we expect a small further cut in the real value of entitlements next academic year.[3]

These cuts will be making life much harder for many students, who are already on tight budgets. In a recent survey by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), half of students reported financial difficulties and 91% that they were either somewhat or very worried about the rising cost of living. More than three-quarters (77%) of students were concerned that the rising cost of living may affect how well they do in their studies, and nearly three in ten (29%) reported they were choosing to miss non-mandatory lectures or tutorials to save on costs.

Many students are falling through the cracks in the government’s ‘cost of living’ support package. They are typically not eligible for benefits, and so are not entitled to targeted payments for those on low incomes. Most households received £400 towards their energy bills this winter but, as others have pointed out, we still do not know whether students living in halls will be eligible for payments through an expansion of that scheme. When asked, government ministers have pointed to universities’ own ‘hardship funds’ and to £261 million of funding from the ‘student premiums’. This overstates the funding available to support students in financial hardship,[4] and the real value of funding being provided has in fact been cut compared with last year.

Another concern is that the expectation of financial hardship might lead some prospective students to decide against going to university in the first place. As shown in Figure 1, a 21-year-old student could earn nearly £1,200 more working in a minimum wage job this academic year than they will receive in maintenance support. This gap is set to increase to more than £2,000 next academic year – the biggest gap since the national minimum wage was introduced in 1999.[5]

Correcting the fall in maintenance loan entitlements will be less expensive for the taxpayer than it may at first appear. This is because students can be expected to repay a portion of any extra maintenance support over the coming decades. We estimate that restoring maintenance loan entitlements this academic year to the same real value they had in 2020–21 would cost £0.9 billion for the cohort starting university in 2022, or around 70% of the initial outlay.[6] Completely correcting forecast errors made in the last two years would cost £1.3 billion for this cohort.

The government has recently hinted that a reform of how maintenance loans are uprated may be coming. That would be welcome. The principle of uprating entitlements with forecasts for inflation is sound, but the most up-to-date inflation forecasts available should be used, and any forecast errors should be corrected in the following year. Alternatively, maintenance loan entitlements could be tied directly to the minimum wage, as suggested by the Augar Review. This would ensure some link with the earnings students forgo in order to study.

In addition, the government should start uprating the lower parental earnings threshold, which governs eligibility for means-tested maintenance support, either with average earnings or with inflation. This threshold has been frozen in nominal terms at £25,000 since 2008, amounting to another stealth cut. As nominal earnings rise, fewer students currently qualify for the maximum each year, and others become eligible for less support, even though their parents may be no better off.

See our student finance calculator here >>>

Footnotes

[1] As a result of reforms announced in February, different repayment terms will apply to students starting courses from 2023 onwards.

[2] This analysis focuses on English-domiciled students, but living cost support for students varies across the UK. Low-income students domiciled in Scotland or Northern Ireland are entitled to less support than those in England, although the Northern Ireland Economy Minister recently announced that maintenance loans in Northern Ireland will increase by 40% next academic year.

[3] The most recent forecast for CPI in the year to 2024Q1 is 2.5%. Typically, we would expect maintenance entitlement in 2023/24 to increase by 1.8%, in line with the forecast for RPIX in Q1 2024 from the OBR’s March 2022 economic and fiscal outlook. If the government instead increased entitlements next year in line with the OBR’s most recent forecast (2.8%), a further real cut could be avoided.

[4] The £261 million appears to refer to recurrent grant funding from the Office for Students, which includes £41 million for the disabled students’ premium. The remaining funding is ‘to support successful student outcomes’ and includes funding for access.

[5] Earnings on the minimum wage for a 21-year-old are expected to rise substantially next academic year, as the 21- to 22-year-old minimum wage rate is set to be abolished.

[6] This uses the IFS student finance calculator and assumes that support in 2022–23 is restored to the same RPI real level as in 2020–21, and is subsequently uprated with RPI. The cost is the total accounting write-off, using the ONS methodology. For the cohort starting university in 2023, this cost would be £0.5 billion.