Post-financial-crisis, public sector borrowing – the gap between government revenue and spending – has fallen and, at the March 2019 Spring Statement, it stood below its long-run historical average. However, a number of changes have occurred since March, or loom on the horizon. The new accounting treatment of student loans dispels a ‘fiscal illusion’ that was previously flattering headline measures of borrowing. The September 2019 Spending Round has, according to the government, ‘turned the page on austerity’. The most recent Bank of England growth forecasts warned of the chances of an imminent recession. Finally, the Brexit process (perhaps) risks delivering a significant adverse shock to the public finances via a non-negotiated exit from the EU.

In this chapter, we produce an updated baseline forecast and look ahead to analyse a variety of scenarios for the medium term. We discuss the impact of a near-term downgrade in the growth outlook even with a smooth Brexit; a no-deal Brexit; and a potential further permanent fiscal loosening – for example, to implement cuts to income tax that were a part of the prime minister’s platform during the Conservative leadership contest.

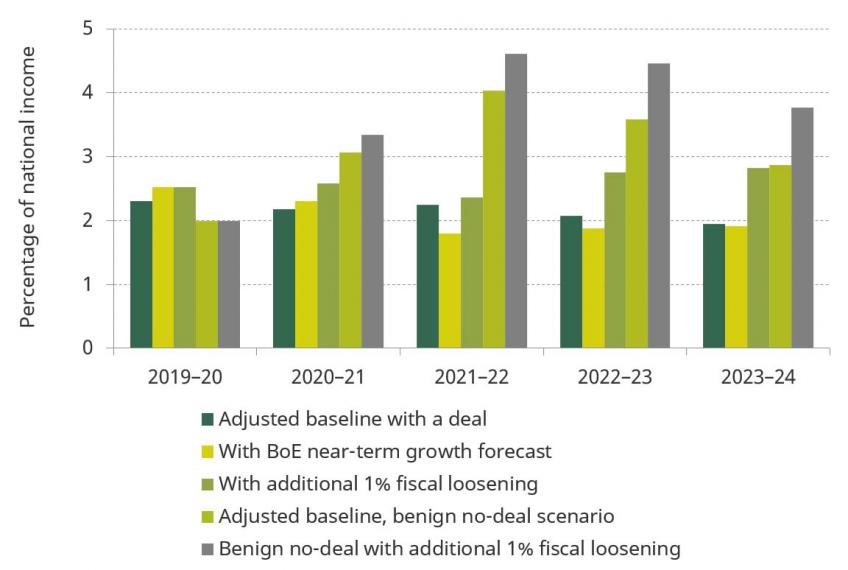

Medium-term projections for public sector net borrowing in five economic scenarios

Key findings

- A decade after the financial crisis, the deficit has been returned to normal levels, but debt is at a historical high. The latest estimate for borrowing in 2018–19, at 1.9% of national income, is at its long-run historical average. However, higher borrowing during the crisis and since has left a mark on debt, which stood at 82% of national income, more than twice its pre-crisis level.

- Given welcome changes to student loan accounting, the spending increases announced at the September Spending Round, and a likely growth downgrade (even assuming a smooth Brexit), borrowing in 2019–20 could be around £55 billion, and still at £52 billion next year. Those figures are respectively £26 billion and £31 billion more than the OBR’s March 2019 forecast. Both exceed 2% of national income.

- A fiscal giveaway beyond the one announced in the September Spending Round could increase borrowing above its historical average over the next five years. With a permanent fiscal giveaway of 1% of national income (£22 billion in today’s terms), borrowing would reach a peak of 2.8% of GDP in 2022–23 under a smooth-Brexit scenario, and headline debt would no longer be falling.

- Even under a relatively orderly no-deal scenario, and with a permanent fiscal loosening of 1% of national income, the deficit would likely rise to over 4% of national income in 2021–22 and debt would climb to almost 90% of national income for the first time since the mid 1960s. Some fiscal tightening – that is, more austerity – would likely be required in subsequent years in order to keep debt on a sustainable path.

- Over the longer term, keeping debt falling as a share of national income whilst funding an additional loosening would rely on a strong growth performance and an orderly Brexit. Even if a Brexit deal is secured, there would be a strong case for the chancellor to resist any calls for a substantial package of permanent tax cuts or further increases in day-to-day spending unless these are to be covered by tax rises of a similar size.