The largest student loan reform since 2012 will reduce the cost of loans for high-earning borrowers but increase it for lower earners.

Today the government has announced the largest changes to the student loans system in England since fees were allowed to triple in 2012. Starting with the 2023 university entry cohort, graduates will pay more towards their student loans each year and their loan balances will only be written off 40 years after they start repayments. For the same cohorts, the interest rate on student loans will be reduced to the rate of increase in the Retail Prices Index (RPI), a large cut of up to 3 percentage points. Maximum tuition fees will be frozen in nominal terms until the 2024/25 academic year.

These changes will transform the student loans system. While under the current system, only around a quarter can expect to repay their loans in full, around 70% can expect to repay under the new system. This is partly due to substantially higher lifetime repayments by students with low and middling earnings and partly due to less interest being accumulated on loans. The long-run benefit for the taxpayer will be around £2.3 billion per cohort of university entrants, as higher repayments by borrowers with low or middling earnings will be partly offset by lower repayments of high-earning borrowers.

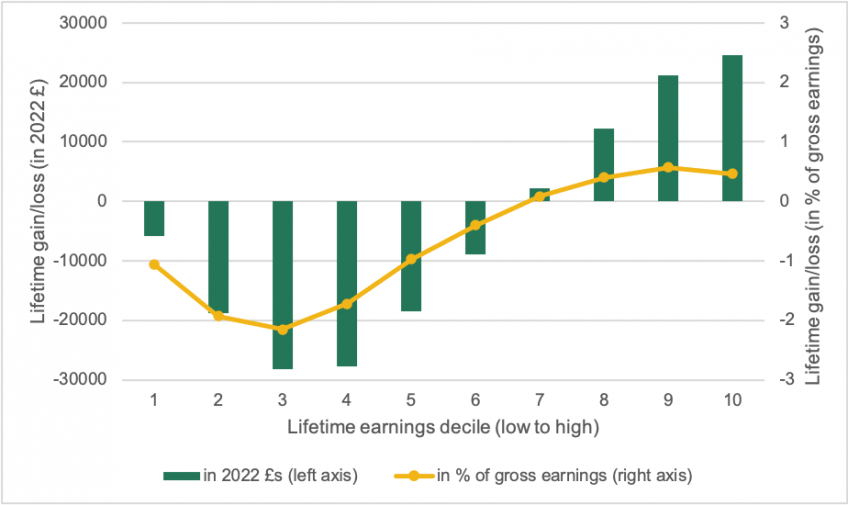

Figure 1. Impact of today’s announcements on student loan borrowers by lifetime earnings decile (2023 entrants)

Source: Author’s calculations using IFS student finance calculator.

Distributional implications

The impact of the announced reforms on student loan borrowers varies substantially depending on their lifetime earnings. Figure 1 shows gains and losses adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). Those with the lowest lifetime earnings lose comparatively little from the announced reform, because they will rarely earn more than the repayment threshold for student loans even under the new system. Those with below average but not the lowest earnings (3rd and 4th decile of borrowers’ earnings) stand to lose the most at around £28,000, as they will in many cases still not pay off their student loans under the new system, but will make repayments for ten years longer and on a larger chunk of their earnings than under the current system.

Graduates with higher middling earnings will nearly always pay off their loans under the new system, but would not have under the old system. For them, the effect of lower interest rates roughly balances out the effect of the lower repayment threshold and the longer repayment period. Finally, the highest earners would have paid off even under the current system; they gain £25,000 on average from the lower interest rate, and the lower repayment threshold merely forces them to pay their loans off more quickly.

As a percentage of lifetime earnings, the reform affects borrowers with low but not the lowest earnings the most (yellow line). For them, the reform translates into a lifetime earnings loss of more than two percent, or more than two pence in each Pound they will ever earn. However, these lower earners will still pay back around £9,000 less on average than the highest earners, so their student loans will still be subsidised by the taxpayer. Their losses relative to the current system arise because the taxpayer subsidy for these graduates will be substantially smaller under the new system than it is under the current system.

The reform package also entails substantial redistribution across genders: men stand to gain on average, whereas women are set to lose. On average, men will repay around £3,800 less towards their student loans under the new system, whereas women will pay £11,600 more. This is because women tend to spend more time out of work than men and on average earn less than men even when in work. As a result, men are much more likely to pay off their loans and benefit from lower interest rates.

Impact on the taxpayer

We estimate that the proposed changes will reduce the long-run taxpayer cost of student loans by £2.3 billion in undiscounted 2022 real terms (inflation-adjusted using RPI). Per borrower, the long-run taxpayer cost of issuing student loans will fall by around £6,200; this will come mostly from higher repayments but also partly from lower outlay due to the freeze in tuition fees. Notably, the taxpayer cost of funding men’s student loans will actually increase as a result of the reform; as a result, the saving on women’s student loans alone is greater than the total at £2.6 billion.

Thanks to an unusual quirk in the way student loans appear in the government accounts, these changes considerably help the government deficit in the short run. We expect the short-run budget deficit impact of student loans to the 2023 cohort to fall by around £6.3 billion, with subsequent hits to the deficit further down the road as new loans accumulate less interest. This will please the Treasury.

Discussion

The new system has much to recommend it. Lower interest rates mean that student loans are now quite a good deal for all students, whereas previously students whose parents could afford to pay the fees upfront, and who were confident that they would earn enough to pay back the loan in full, were substantially worse off using the loan system. This is no longer the case, which should raise trust in the system.

The reform also makes the system much more transparent for student. For most, it is now appropriate to think of their student loans as more akin to more familiar consumer or mortgage loans. That is because a majority can now expect to pay off the loan at some point, rather than have it written off. Alongside the cut in the interest rate this also means that repayments will more closely correspond to amounts borrowed. These changes are broadly in line with the recommendations of the Augar Review of post-18 education and funding, to which these proposals are a response.

However, these advantages of the new system need to be weighed against its strong negative impact on lower-earning graduates. As a result of the cut in the repayment threshold, they will pay more in the years after graduation, and the extension of the time period for repayment to 40 years means that they will be paying back for longer. That said, given the frequency with which changes have been made to the system over the past decade, the idea that this will in fact be the basis on which people are being charged in the mid-2060s – 40 years from the point at which those affected will graduate – is perhaps a little optimistic.

This is an initial response to changes to the student loans system for future cohorts that were announced on 24 February. It was updated on 2 March to reflect a tweak in the uprating of earnings thresholds that we missed in our initial analysis.

We will continue to analyse the contents of today’s announcement and provide further commentary, including on student loans changes for current borrowers, student number controls, minimum eligibility requirements, and changes to further education and sub-degree qualifications.