The government today announced that it plans to increase the cap on tuition fees for England-domiciled undergraduate students from £9,250 to £9,535 for the 2025-26 academic year. This is in line with the Office for Budget Responsibility’s latest forecast for inflation as measured by RPIX (3.1%).

This ends a long-running cash freeze in the fee cap, which had been increased only once since 2012 (from £9,000 to £9,250 in 2017). Compared to a continued freeze, the increase in fees will spare the higher education sector a further real-terms cut to teaching resources of around £390 million next academic year.

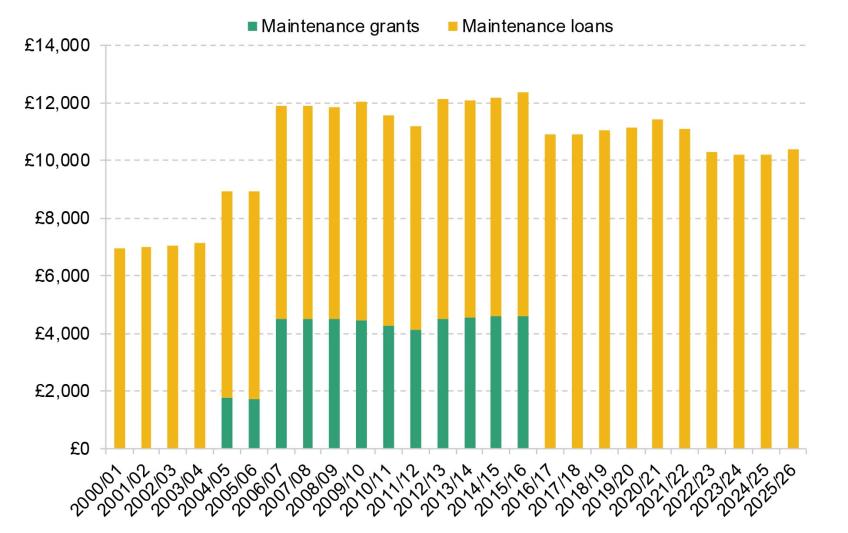

As well as increasing tuition fees, the government has confirmed that maximum maintenance loan entitlements will increase by £414 in the 2025-26 academic year. A student living away from home, outside London and with a household income below £25,000 was able to borrow up to £10,227 for the current academic year, so this appears to represent around a 4% cash-terms increase in entitlements – or perhaps 1.6% once rising prices are taken into account. This does little to reverse the substantial real-terms cuts to the generosity of the maintenance system since 2020-21, leaving the poorest students able to borrow around 9% less in real terms than in 2020-21 (the recent high point).

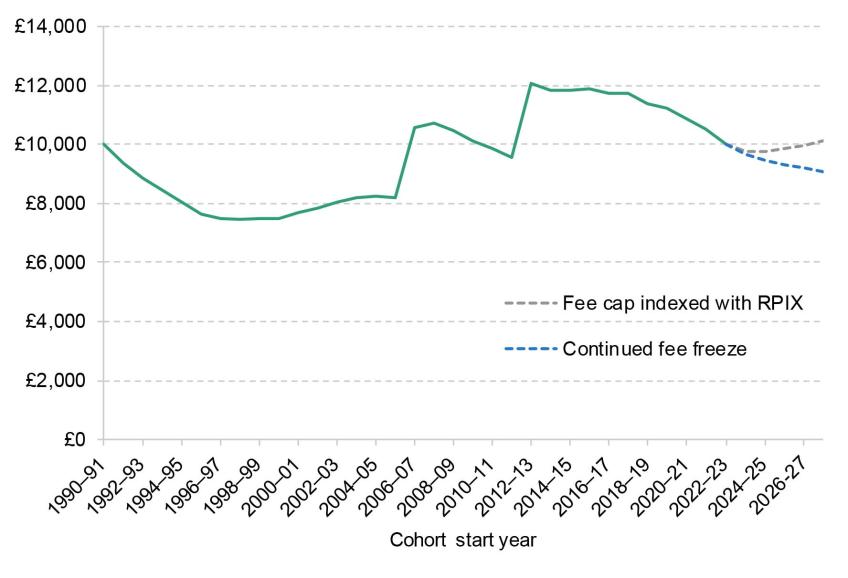

A historical squeeze on teaching resources

As a result of the long-term tuition fee freeze, universities’ resources for undergraduate teaching have been eroded in real terms. Increases in teaching grants – which now account for around a tenth of overall teaching resources – have not made up for the substantial real-terms cuts in the fee cap. For students starting in 2022, teaching resources per year were £10,010 – just barely higher in real terms than in 2011, the year before the tuition fee cap was tripled.

Universities have so far been able to partially make up for falling income from domestic students with increased international student fee income. Non-EU international students accounted for 38% of full-time entrants to English universities in 2022-23. International students are not subject to the tuition fee cap and typically pay higher – in some cases much higher – tuition fees. But falling student visa numbers suggest that universities can no longer rely on ever-increasing international fee income. Maintaining the tuition fee freeze indefinitely – at least without extra direct teaching grants to universities – looked unsustainable.

If the government continues to increase fees in line with RPIX each year, the tuition fee cap could reach £10,680 in 2029-30, on current forecasts. If the government is planning to continue to raise the fee cap with inflation, it should say so – and provide some certainty to universities and prospective students alike.

Upfront funding for higher education per student per year under different policies on tuition fees, 2024/25 prices

Note: Higher education figures are upfront resources available for teaching home undergraduate students, and cohort-based numbers divided by 3 – an approximate course length in years. We assume per-student teaching grants are constant in real terms after 2024-25 and fee waivers and bursaries are constant as a share of tuition fees. Real-terms figures reflect forecast GDP deflator.

Cuts to the generosity of maintenance support will be baked in

The last few years have seen a substantial effective cut to maintenance loans (which support students with their living costs). Under the previous government, loans were increased each year in line with forecast inflation – but the numbers weren’t revisited when inflation turned out higher than expected, as happened for several years in a row. Based on CPI, a measure of consumer prices, entitlements were cut by 10.5% in real terms between 2020-21 and 2024-25.

Today’s announcement will see maintenance entitlements increase by slightly more than forecast CPI inflation next academic year. But that will still leave support for the poorest students around £1,030 (9%) lower in real terms than support for an equivalent student in 2020-21.

Maximum maintenance support entitlements per year for students living away from home, outside London, 2024/25 prices

Note: All monetary amounts are in CPI real terms. In order to align with government calculations, the price level for an academic year is taken to be the price level in the first calendar quarter falling into that academic year. In each academic year, the chart reflects the maintenance system as it applied to new students.

Who will pay for higher tuition fees and maintenance loans?

Both the increase in tuition fees and maintenance loan entitlements will add to student borrowing. Under current student loan terms, we expect around a quarter of the additional loans extended as a result of today’s announcement will eventually be written off and met by the taxpayer. These extra loan write-offs count as capital spending, and so don’t impact the government’s ability to meet its ‘stability rule’ (current budget balance) – unlike an increase in direct grants to universities or maintenance grants, which would count as current spending.

For students, the immediate impact of today’s announcement will be higher tuition fees, and a very slight real-terms increase in living cost support next year. For many, this will mean graduating with higher cash-terms student loan balances. In the long-run, we expect graduates will eventually repay around three-quarters of any additional loans.

But for most students, the impact on actual student loan repayments will not be felt for many years. This is because until the loan is paid off, monthly loan repayments only depend on a borrower’s earnings and not on their outstanding loan balance. Amongst those starting courses in 2025 and studying for three years, less than a third of borrowers will see any difference in their loan repayments before they reach the age of 40 (assuming they start courses at age 18). They might then continue making loan repayments for a few more months than they otherwise would have. Around one in five borrowers will never repay any more, as they would never clear their loans even if the freeze continued.

Kate Ogden, Senior Research Economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said:

“University Vice Chancellors will be breathing a sigh of relief that the government is not extending the tuition fee freeze, sparing universities a further real-terms cut to resources of around £390 million next academic year. Of course, higher fees today mean higher student loan repayments in the long run – with graduates eventually repaying around three-quarters of the extra borrowing resulting from today’s announcement.

Living cost support for students will also be protected in real terms. But crucially, the government has decided not to reverse the substantial real-terms cuts in the generosity of support seen in recent years. Even after the uplift, the poorest students will be entitled to borrow around 9% less next academic year than an equivalent student 5 years earlier.”