Executive summary

In this major report of the Pensions Review, led by the Institute for Fiscal Studies in partnership with the abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, we consider the role of the state pension in the UK pension system, analyse the key challenges for future generations of pensioners and set out policies that would improve the current system.

The state pension: where are we?

• The state pension can be claimed from age 66 (rising to 67 by 2028). The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) estimates that by the mid 2030s, 80% of those reaching the state pension age will receive the full ‘new state pension’, currently worth £203.85 per week. At 30% of median (full-time) earnings, the full new state pension is at a higher level than the basic state pension was at any point since at least 1968.

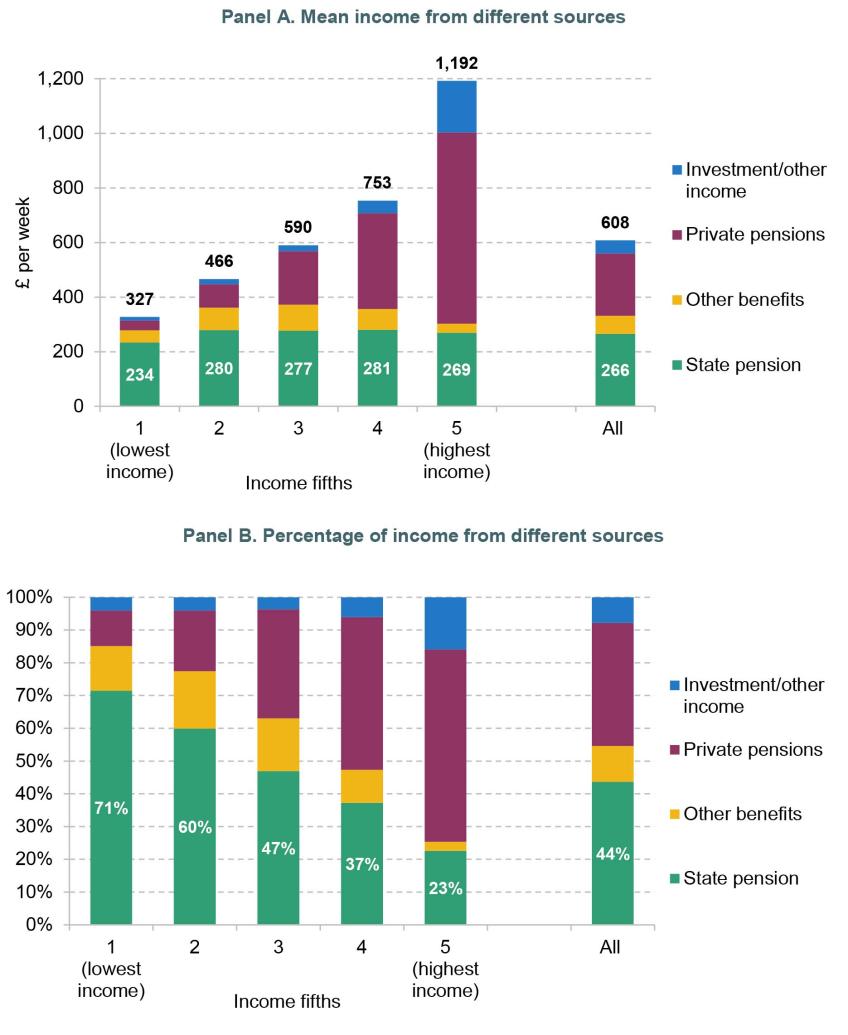

• The state pension is an important source of income across the income distribution, although more important for poorer households. For example, among households with someone aged 66–70 where no one is in paid work, the state pension makes up 71% of income for the poorest fifth and 23% for the richest fifth. Indeed, if one wanted to buy an index-linked annuity to provide a pension that was equal to the current value of the new state pension (and then price indexed) from the age of 66, then that would require an outlay of over £200,000. This is a significant sum even at the top of the income distribution.

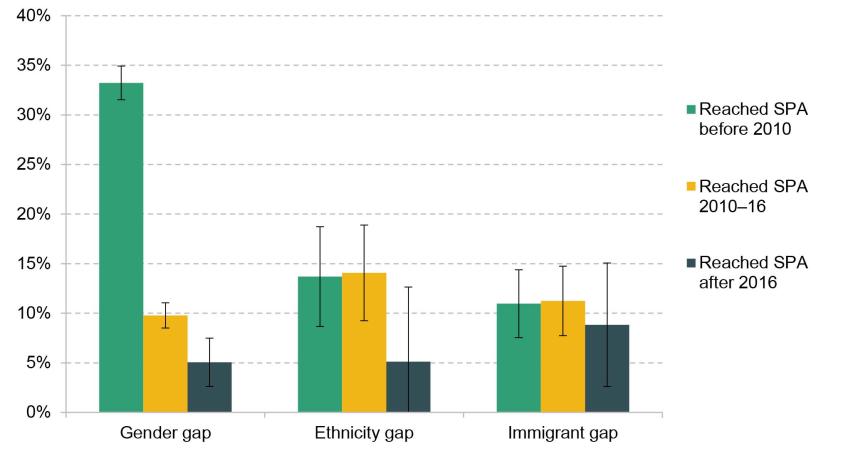

• Although many older pensioners – and a particularly large proportion of women who reached state pension age before 2010 – are receiving much less than the full new state pension, most new retirees receiving this amount (alongside any means-tested housing benefit and support for council tax) are close to or above the relative poverty line, even if they have no other income.

• Government spending on social security payments to pensioners is expected to be £152 billion (5.9% of national income) in 2023–24. Of this total, spending on the state pension, pension credit and winter fuel payment comprises £132 billion, or 5.1% of national income (the vast majority of the rest of the social security spending is on disability benefits and means-tested housing benefit). The 5.1% compares with 4.4% of national income spent on these payments (state pension, pension credit and predecessors, and winter fuel payment) in 1983–84 and 4.2% of national income in 2003–04.

Challenges facing the state pension

We have identified four key challenges facing the state pension system:

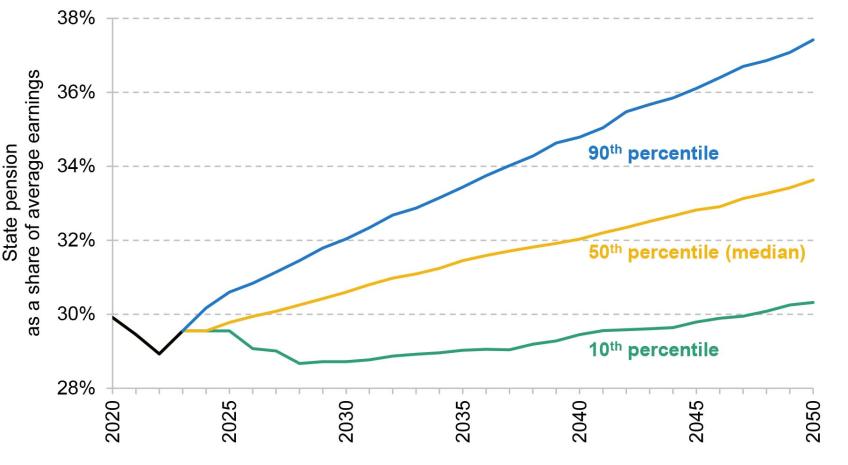

1 The ageing population will add considerable pressure on public finances in coming decades. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), under current population projections and government policy (maintaining the triple lock and the state pension age rising to 68 by 2046), spending on the state pension, pension credit and winter fuel payment is expected to rise by 1.2% of national income (£32 billion per year in today’s terms) by 2050. One key driver of this is that there are expected to be 25% more pensioners in 2050 than today, with another driver being how the state pension is indexed. The pressures due to health and social care are much bigger, with spending projected to rise by 4.1% of national income (£105 billion per year in today’s terms) over the same period.

2 While there is naturally a debate about the right level of the state pension, the ‘triple lock’ indexation policy (which increases the state pension each year by the highest of inflation, average earnings growth and 2.5%) ratchets up the value of, and spending on, the state pension over time in a way that creates uncertainty around what the level of the state pension will be relative to average earnings, and for the public finances. Compared with increasing the state pension in line with average earnings, we project that – on its own – the triple lock could easily cost anywhere between an additional £5 billion and £40 billion per year in 2050 in today’s terms.

3 If the government wants to rein in state pension spending, then relying only on raising the state pension age to achieve this, rather than moving to less generous indexation, would hit those with lower life expectancy harder. This is because the same increase in the state pension age has a larger proportional impact on the expected state pension wealth of people who die at younger ages than for people who live longer. People who die at younger ages do not benefit as much from the triple lock, which increases the value of the state pension in the future. Groups with lower life expectancy include poorer people (compared with richer people).

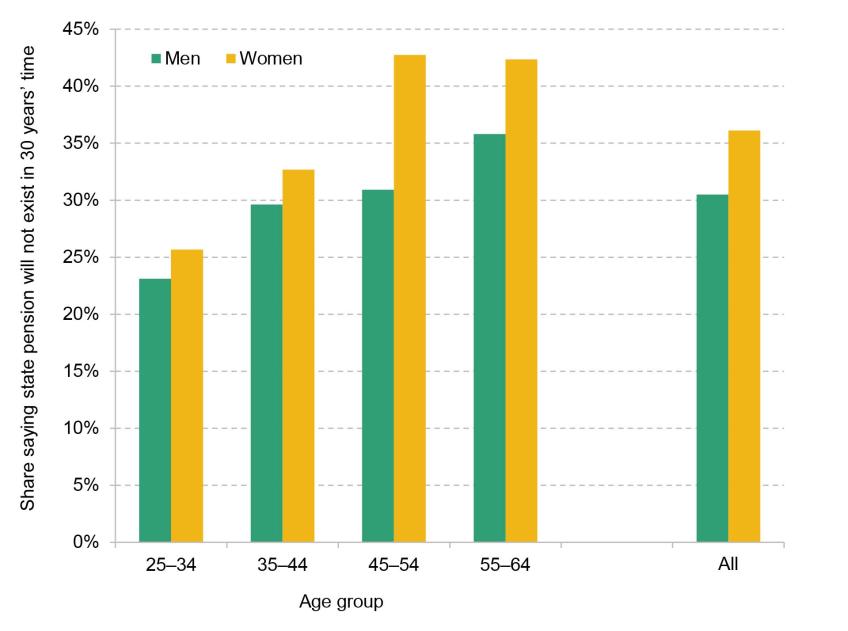

4 Despite its new-found simplicity, there is a mixture of confusion and pessimism about the state pension. Although the state pension has increased at least as fast as inflation every year since 1975, 38% of people think that in the next 10 years it will not keep up with inflation. Pessimism is also widespread; a third of people do not think the state pension will exist in 30 years’ time.

It is important to note that the new state pension at its current level is just about enough by itself to keep most people out of income poverty (according to standard government metrics). However, there are some people – in particular, single households living in private rented accommodation – for whom the new state pension and means-tested benefits are not enough to keep them above the income poverty line. Take-up of means-tested benefits among retirees is also far from complete; the design of these benefits will be considered in a later report of the Pensions Review.

Even for households for whom the new state pension is enough to keep them above the income poverty line, it is not enough on its own for a comfortable retirement or to provide most people with a standard of living they have been used to in working life. Instead, for most people, the state pension is a basis for building upon with their own savings, rather than the whole of their pension provision.

The future of the state pension: a new way forward

Despite these challenges, our view is that the state pension is not in need of wholesale change. Indeed, its structure has much to commend it. Given where we are, we think we should retain a flat-rate state pension that is neither earnings-related (which would mean higher state pensions for people with higher earnings over their lifetime) nor means-tested (which would mean lower state pensions for pensioners with higher private incomes). Although the state pension is higher than in the past, given its current level we think it should continue to be accessible from a single universal state pension age, rather than being made available from an earlier age at a permanently reduced amount.

However, improvements are needed to address the key challenges set out above, in order to build on the strengths of the current system and provide a sustainable long-term future for the state pension.

We suggest a new ‘four-point pension guarantee’ to achieve this:

1 There will be a government target level for the new state pension, expressed as a share of median full-time earnings. Increases in the state pension will in the long run keep pace with growth in average earnings, which ensures that pensioners benefit when living standards rise.

2 Both before and after the target level is reached, the state pension will continue to increase at least in line with inflation every year.

3 The state pension will not be means-tested.

4 The state pension age will only rise as longevity at older ages increases, and never by the full amount of that longevity increase. To increase confidence and understanding, the government will write to people around their 50th birthday stating what their state pension age is expected to be. Their state pension age would then be fully guaranteed 10 years before they reach it.

To set the target level, as the government has done with the minimum wage, politicians should state what they believe to be an appropriate level for the new state pension (and the basic state pension) relative to average earnings (as measured by median full-time earnings). They should then legislate a pathway to meeting that target with a specific timetable. This would result in an explicit commitment from the government to target a level of state pension relative to average earnings, which would then be maintained in the long run too.

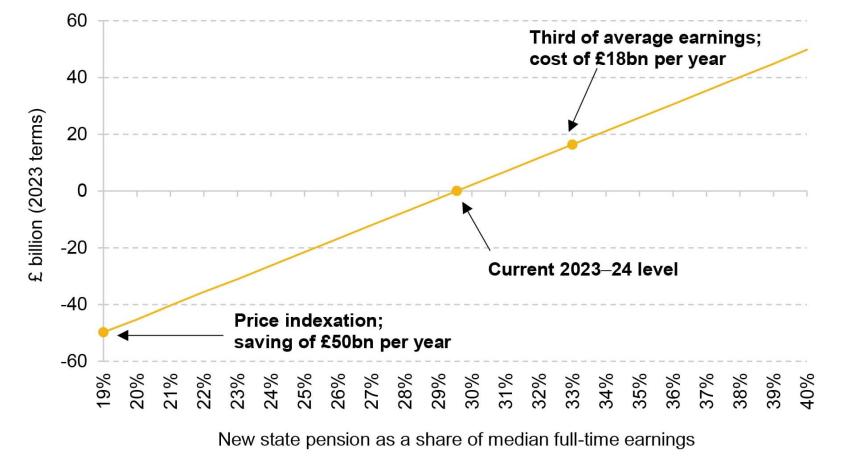

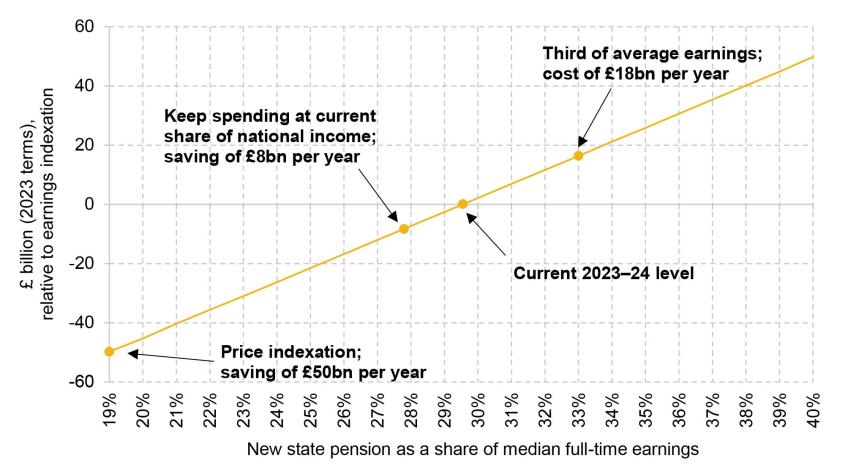

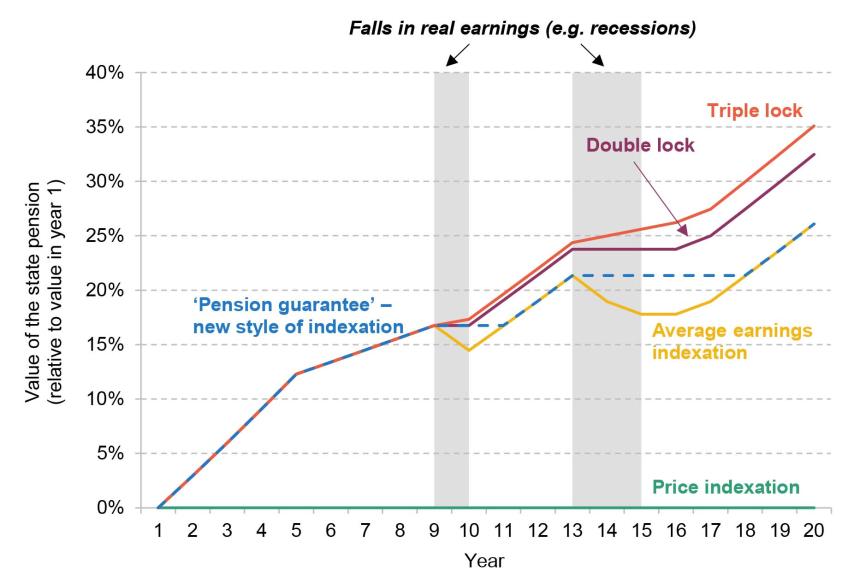

In choosing the level of the new state pension, the government has to consider the trade-off between a higher income for pensioners and the public finance implications that will have. As an illustration of the cost of increasing the value of the state pension relative to average earnings, Figure ES.1 shows the cost in 2050 of different levels of the state pension (measured in today’s terms) relative to keeping the state pension, as today, at 30% of median full-time earnings (which itself would lead to a saving of £24 billion per year in today’s terms compared with the expected cost of the triple lock).

Figure ES.1. Impact on state pension spending in 2050 relative to earnings indexation from 2023 onwards

Note: Current level of the new state pension relative to median full-time earnings is 29.6%.

Source: Authors’ calculations using OBR 2023 projections of state pension spending and long-term economic determinants.

For example, increasing the state pension to be a third (33.3%) of average earnings in 2050 would cost an additional £18 billion per year in today’s terms (about 0.7% of national income), compared with keeping the state pension at the current 30% of average earnings. It would also deliver a state pension equivalent (in terms of today’s earnings) to £230 per week, or £26 higher, than today’s full new state pension of £204 per week.

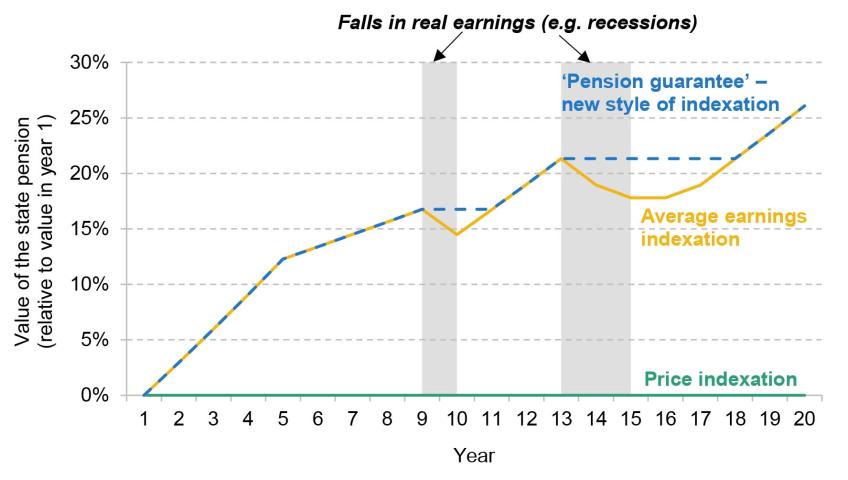

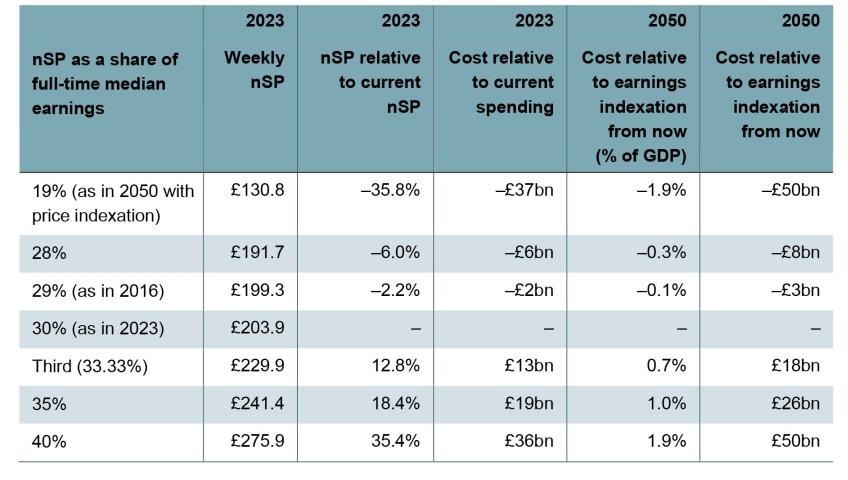

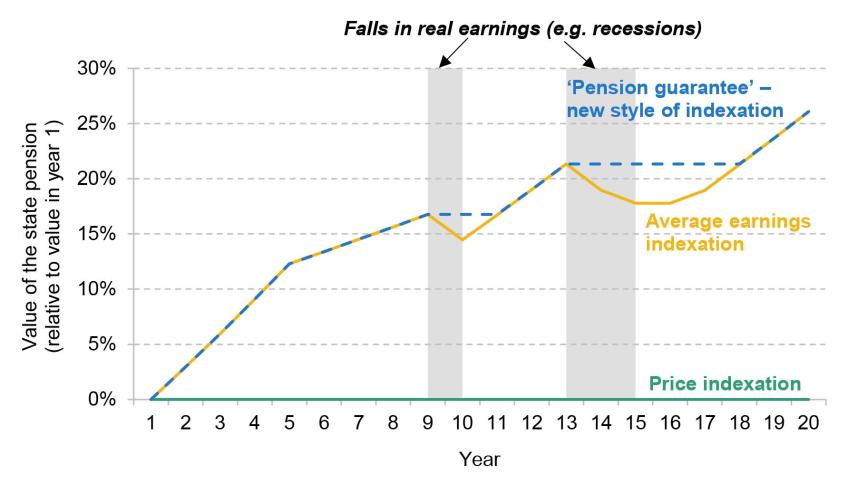

Once the government has chosen and reached a target level for the new state pension relative to average earnings, the state pension should then be indexed in line with our suggested pension guarantee. It is worth noting that this process is how the state pension in Australia is indexed. Figure ES.2 illustrates how this would work in practice by showing the real value of the state pension over time, given an illustrative 20-year period. The figure shows that in periods of relative economic stability, when average earnings growth is above inflation, the value of the state pension rises in real terms, growing in line with average earnings (the blue dashed line follows the yellow line). The rate at which the value of the state pension rises depends on how fast average earnings grow. As the figure shows, when real earnings growth is faster (years 1–5), the real value of the state pension also rises faster than when earnings growth is slower (years 6–9).

Figure ES.2. Illustration of how our suggested new style of indexation would operate

Note: Assumes inflation of 2% and average earnings growth of 5% in years 1–5 and 3% in years 6–9. In the first period of negative real earnings growth, average earnings growth falls to 0% for one year. In the second period of lower average earnings growth, which lasts four years, the rates are 0%, 1%, 2% and 3%. Between the periods of negative real earnings growth, the nominal average earnings growth rate is 4%, as it is in the final three years.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

However, during any period where average earnings growth is below inflation, such as a recession (highlighted in grey in the figure), the value of the state pension rises in line with prices (and is therefore constant in real terms). This protects the purchasing power of the state pension in times of an economic downturn (so the blue dashed line is horizontal and above the yellow line). The state pension then continues to be indexed to prices, rising at the rate of inflation, until it reaches the target level again (so the blue dashed line does not rise until the yellow line reaches it), and then continues to rise again in line with average earnings.

This report sets out our key findings and suggests a way forward for the future of the UK state pension. These policy suggestions are based on new findings in this report, evidence from specially conducted polling and focus groups, and discussions with expert stakeholders. Together with a commitment from the government to target a level of the state pension relative to average earnings, the suggested ‘four-point pension guarantee’ is carefully designed to build on the strengths of the current state pension system and to address some of the key challenges we have identified. In particular, it would help ensure people can have confidence and certainty over the state pension as a future source of income to protect them from poverty and provide a solid bedrock on top of which they can build private pension saving.

Key findings

1. The UK state pension system has a number of attractive features that work well. Much of this follows from the success of the recommendations of the Pensions Commission almost 20 years ago. Following reforms legislated in 2007 and 2014, we are moving towards a flat-rate state pension which most people who spend most of their adult life in the UK will receive in full. The full new state pension is set at a level that means most new pensioners do not need to rely on the means-tested pension credit. Even with no private income, most people receiving the full amount are very close to or above the relative poverty line. The first universal increase in the state pension age was legislated and implemented with relatively little controversy. The state pension age – and the fact it is rising – is relatively well understood.

2. There is widespread pessimism about the future of the state pension, and a mixture of confusion and pessimism about the level of the state pension. Only one in five working-age people (20%) know even approximately how much a full state pension is. Despite it being increased every year by at least inflation since 1975, 38% think that the state pension will rise by less than inflation over the next decade. One-third do not think the state pension will exist in 30 years’ time. This is likely a driver of many (41%) thinking they will not have a good standard of living in retirement.

3. The state pension should remain flat-rate, i.e. neither earnings-related nor means-tested. This maintains the post-Pensions-Commission settlement for a pension system that balances state and private pensions in retirement. Many other European countries provide an earnings-related state pension. However, earnings-related pensions have an unhappy history in the UK, and we sense no political appetite for raising taxes in order to fund bigger state pensions that benefit middle and higher earners in particular. Widespread means-testing of the state pension is not an attractive option when we rely on private saving to supplement the state pension for so many, as it could significantly reduce saving incentives and risk undermining the success of automatic enrolment. The risk of distorted saving incentives applies to most workers, as the state pension is an important source of income for many who are not poor; for example, it makes up nearly half of income for recently retired middle-income pensioners.

4. The UK should maintain a single universal state pension age, rather than introduce an ‘early access’ age in return for a reduced award as is possible in some countries. Allowing early access would mean that people approaching the state pension age would have to make a complex financial decision about the timing of claiming their state pension, which would have long-lasting consequences. It would also complicate the concept of the state pension age, which is perhaps the best-understood part of the system. Allowing early access at a permanently reduced rate would increase individuals’ risk of income poverty at older ages and place greater demands on means-tested support for pensioners. This means the case for allowing early access would be stronger if the state pension were made more generous relative to average earnings. We will consider the case for additional state support for those who find it hard to work prior to state pension age in a later report in this Review.

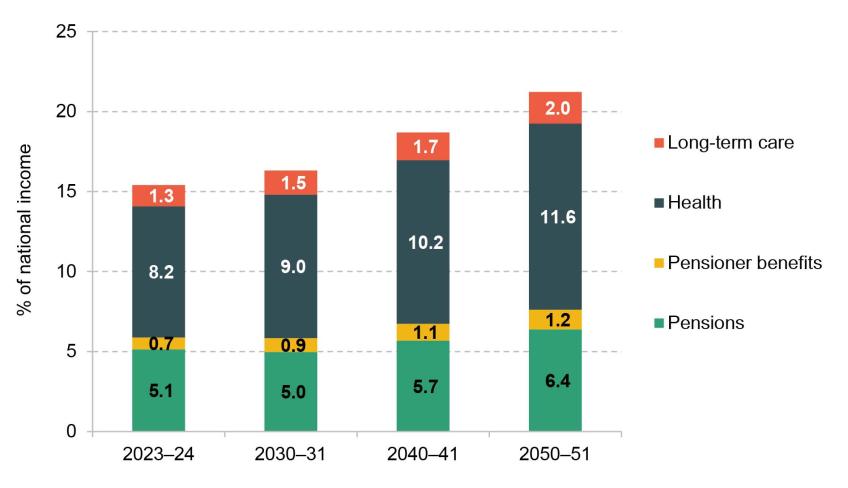

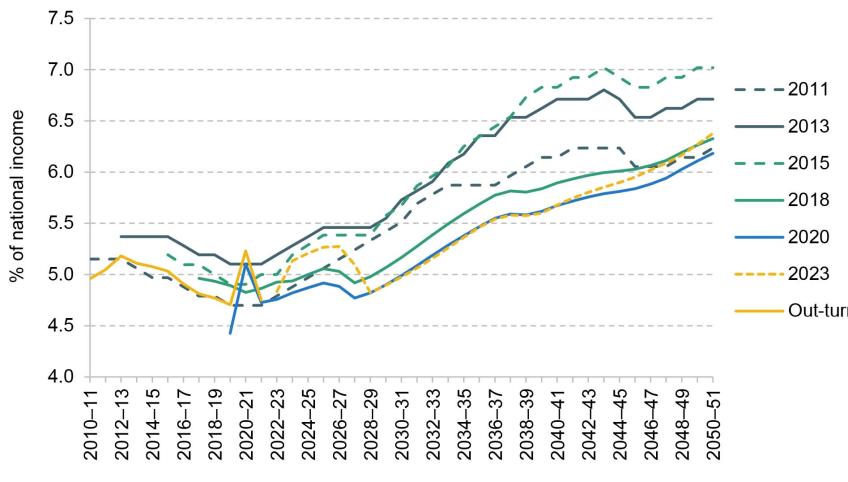

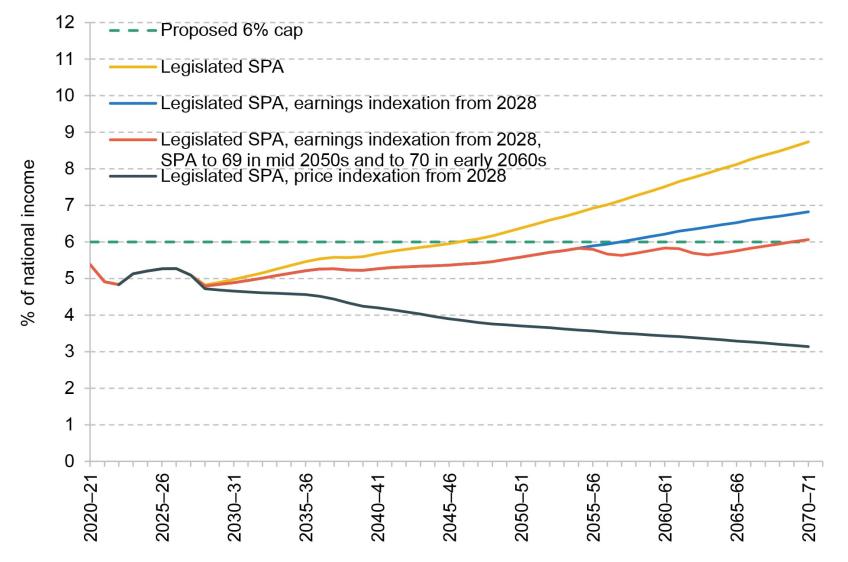

5. The ageing population will add considerable pressure on public finances in coming decades. Under legislated state pension age increases (eventually to 68) and the triple-lock method of indexation, spending on state pension, pension credit and winter fuel payment is projected to rise from 5.1% of national income in 2023–24 to 6.4% in 2050–51 under the OBR’s central scenario. Pressures on the health and social care budgets are even larger – set to push up spending from 9.5% of national income now to 13.6% in 2050–51. While there is considerable uncertainty around these precise numbers, it is clear the ageing of the population represents a substantial challenge for the public finances.

6. The triple lock increases the value of, and thus public spending on, the state pension relative to both prices and average earnings over time. Compared with increasing the state pension in line with average earnings, we project that the triple lock could reasonably be expected to cost anywhere between an additional £5 billion and £40 billion per year in 2050 in today’s terms, equivalent to between 0.2% and 1.6% of national income. A government that wants to control future spending on the state pension, while maintaining the near-universal and flat-rate nature of the state pension, would need to abandon the triple lock or increase the state pension age even further than currently legislated.

7. The latest government-commissioned Independent Review of the State Pension Age proposed that spending on the state pension should be capped at 6% of national income. The projections from that report suggest that even with a state pension age of 70 in the early 2050s, spending on a triple-locked state pension would exceed this cap at that point, though these projections are very uncertain, in particular because of the uncertainty generated by the triple lock. The cap is badly designed – for example, it would allow a much more generous deal to those from small birth cohorts than to those from large cohorts – and it should not be implemented.

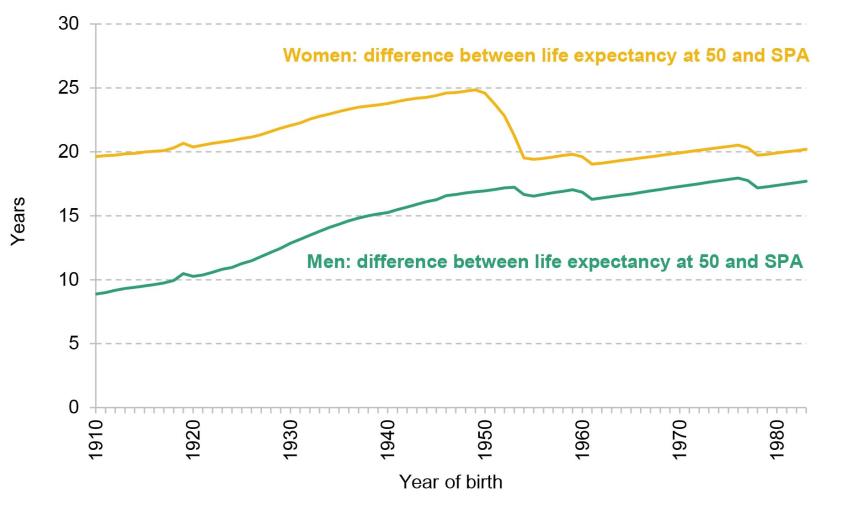

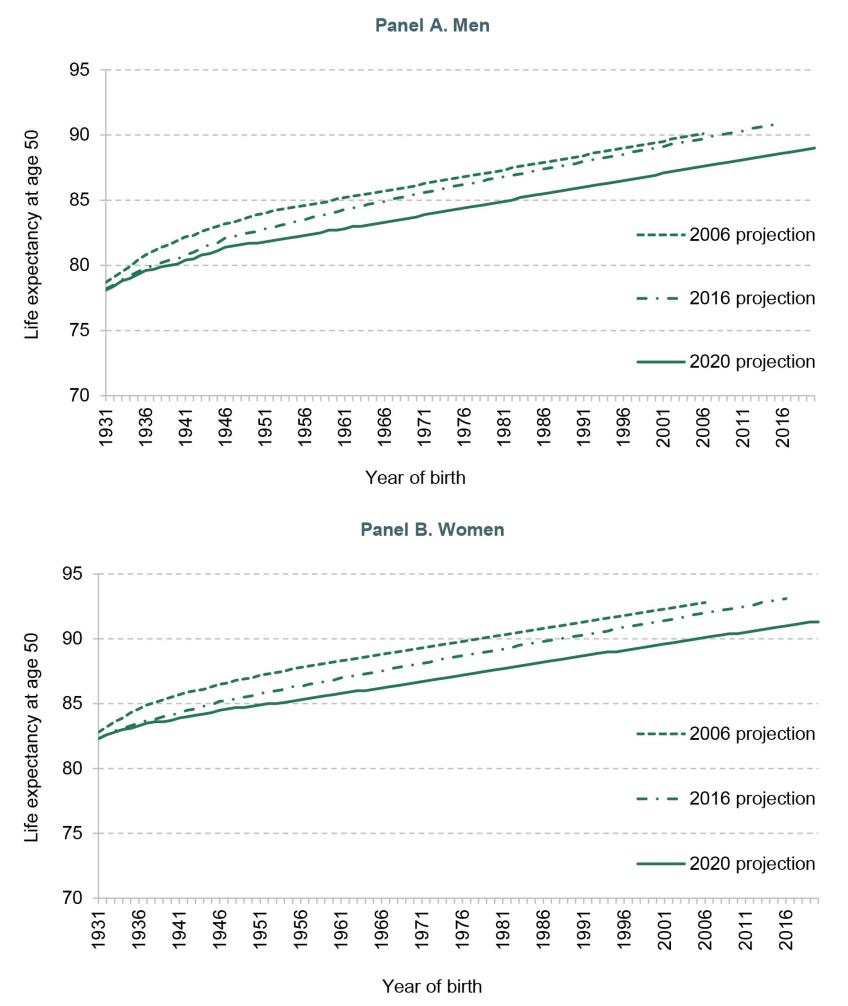

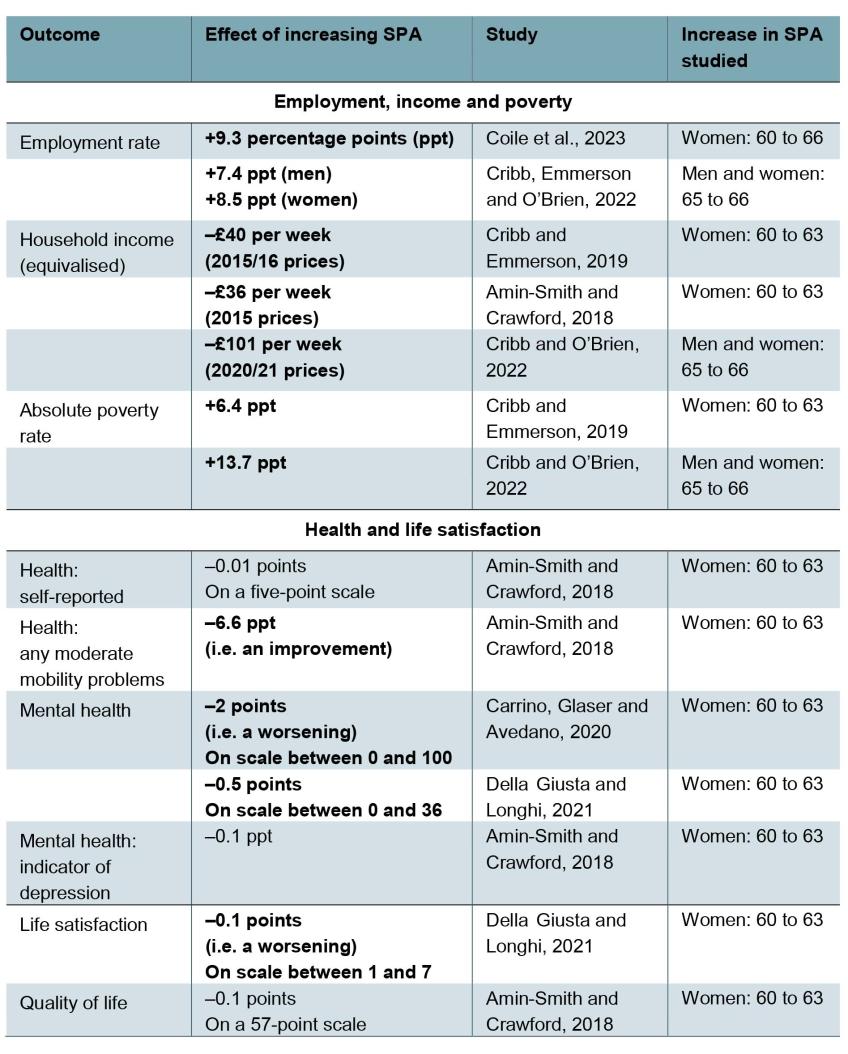

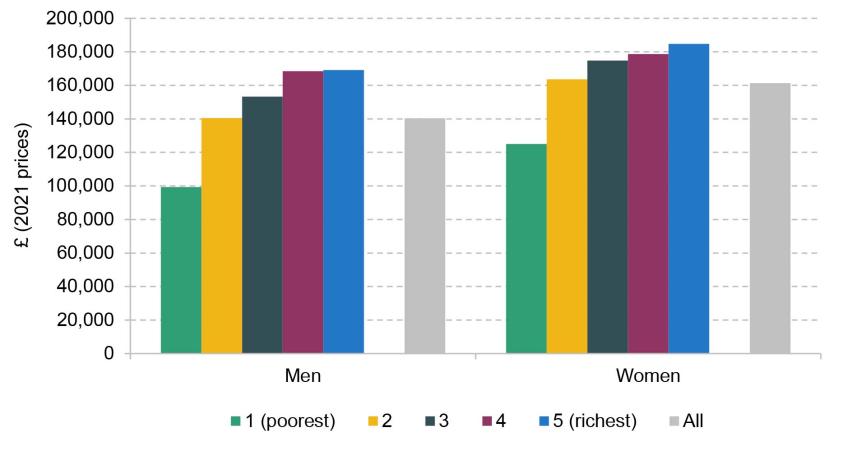

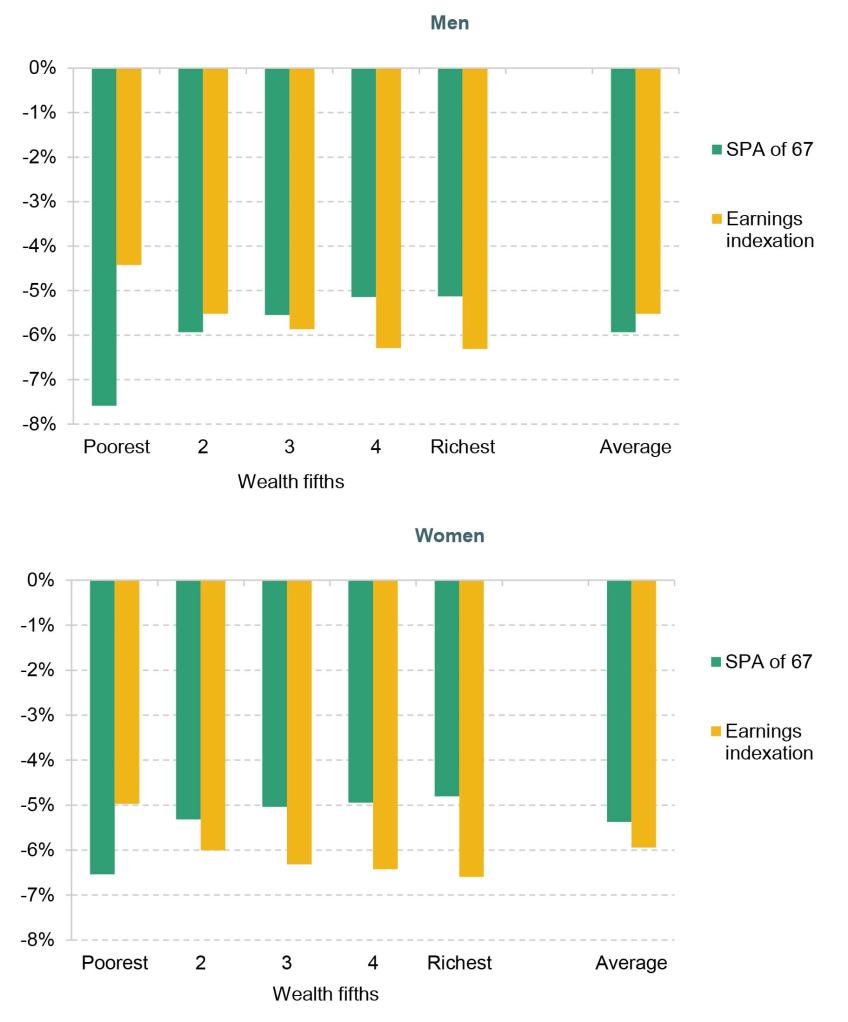

8. Keeping the triple lock while raising the state pension age would hit poorer people more because the loss of a year of income is more important for those with lower life expectancy, as they spend fewer years above the state pension age. On the other hand, those with a higher life expectancy benefit relatively more from the triple lock, as they are more likely to be receiving a generously indexed state pension in their 90s and beyond. If one were to increase the state pension age from 66 to 67 today, that would on average reduce the lifetime value of the state pension by 6%, but it would reduce it by 8% for the poorest fifth of men and by 5% for the richest fifth of men. In contrast, the impact of moving away from the triple lock and to earnings indexation – also a 6% reduction in expected value of the state pension on average – would be a reduction of 4% for the poorest fifth of men and 6% for the richest fifth of men. The patterns for women are similar.

9. The triple lock ratchets up the value of, and spending on the state pension over time in a way that creates uncertainty for individuals around what the level of the state pension will be relative to average earnings, and for the public finances. Because of the ratcheting effect of the triple lock, which locks in any above-earnings-growth increases in the state pension, the range of possible levels of the triple-locked state pension relative to earnings is wide. Based on the past 30 years of inflation and earnings data – and uprating decisions – a reasonable range (occurring 80% of the time) for the state pension in 2050 would be 30% to 37% of median full-time earnings, a range of £10,900 to £13,400 (in terms of today’s earnings). The long-term risks for the sustainability of the public finances also increase the likelihood of other cuts to the state pension system being introduced in future decades, such as an even higher state pension age.

10. The introduction of the new state pension in 2016 and (to a lesser extent) the triple lock since 2010 together have resulted in the full rate of the new state pension approaching 30% of median full-time earnings – higher than the basic pension was at any point since at least 1968. We therefore now have a flat-rate state pension that is more generous, relative to median earnings, than it was when the earnings link was broken by the Conservative government in 1980. Despite this, on average, people in younger generations are likely to receive lower state pension incomes under the flat-rate new state pension than if earnings-related state pensions had not been abolished. Though, due to automatic enrolment, many more people from younger generations are also likely to accumulate at least some private pension wealth.

11. A more generous state pension would of course lead to a higher income for current and future pensioners – and would be particularly valuable to low- and middle-income pensioners – but this would also have implications for public finances. If, for example, the government decided that the new state pension should be worth a third of median full-time earnings, this would mean that the new state pension would be 13% higher than it currently is – £230 per week, or £26 higher, in today’s earnings terms than the current full new state pension of £204 per week – costing an additional £18 billion per year by 2050 (relative to keeping the new state pension at 30% of median earnings).

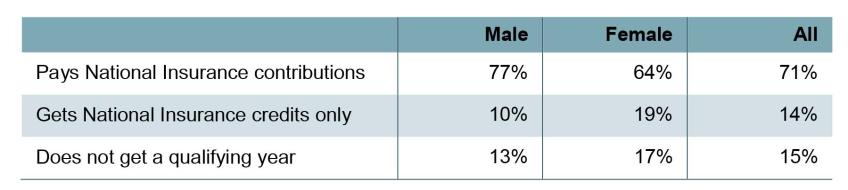

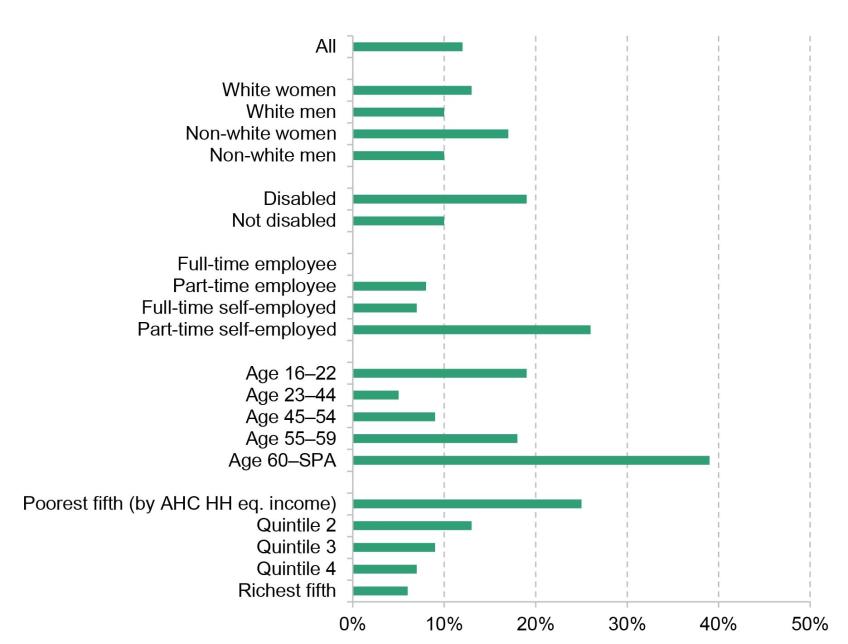

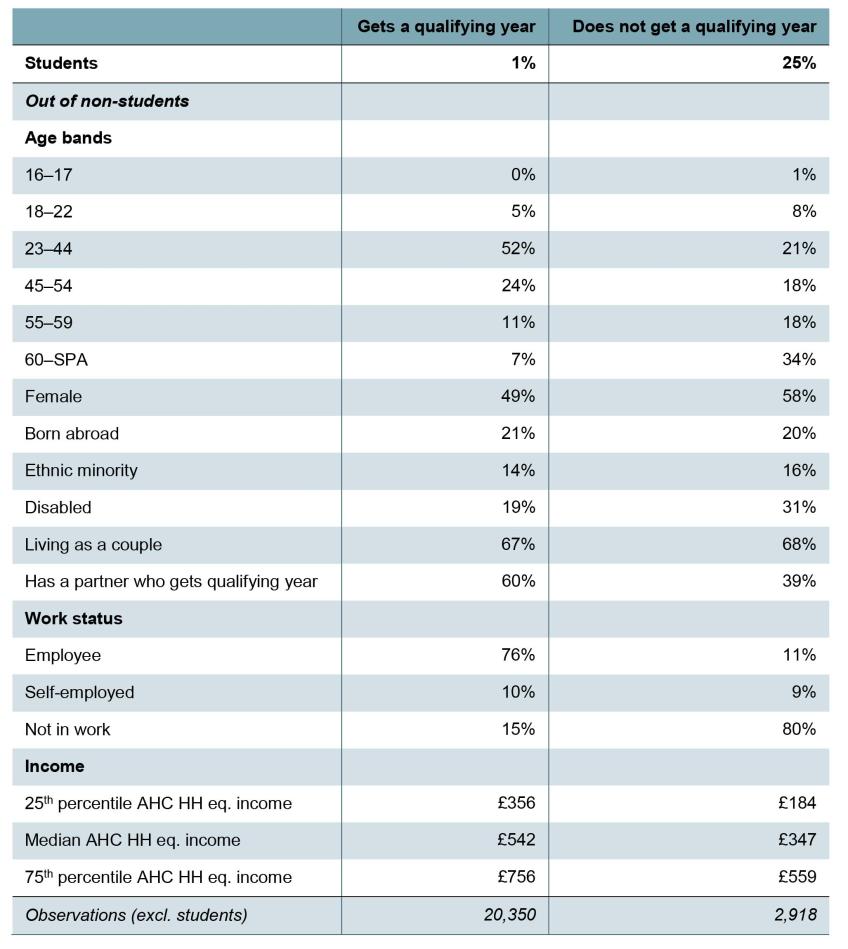

12. Despite many believing so, it is not true that only people paying National Insurance contributions generate eligibility towards the state pension. Ever since 1948, there have been credits for periods of unemployment and incapacity due to poor health. The state pension is now much more generous in its coverage than in the past, with those reaching state pension age after 2010 able to get recognition for time spent out of the labour market due to childcare and other caring responsibilities. There is no longer a reduced pension available to married women for those who got married after 1977. The new state pension offers a better deal to the self-employed than prior to 2016. There are a large number of complex rules over what counts as a ‘qualifying year’ which generates eligibility to a state pension. This leads to various inequities – for example, someone earning £5,000 per year who also receives universal credit will automatically qualify, whereas someone with the same level of earnings but with a higher-earning spouse, who is therefore not eligible for universal credit, is unlikely to qualify. We are rapidly moving to a state pension system in which most people who live in the UK all their adult life get a full state pension. But we are not quite there yet.

13. There is a good case for simplifying the complicated eligibility rules and moving further towards a universal pension where essentially all people build entitlement to a state pension each year of life they live in the UK (up to a cap). This would be a more transparent and arguably fairer system. To the extent that this move would have a cost to the exchequer, the number of years required for a full state pension could rise slightly from 35 years to make it cost neutral (or, if so desired, could be raised further). A more universal state pension would simplify the system, lead to some efficiency savings and reduce the risk of some people inadvertently falling through the net. But the administrative challenge of accurately measuring who is resident in the country in each year would have to be overcome and the change would not lead to significant differences in state pension incomes for most people. In other words, altering the current system might be a substantial administrative challenge benefiting a relatively small group. That said, the obvious, and often unintended, inequities created by the current system mean that a change towards greater universality is, at the very least, worth exploring.

14. Together, our new findings in this report, evidence from specially conducted polling and our discussions with various stakeholders suggest a ‘four-point pension guarantee’. This guarantee is designed to: give people more confidence and certainty over what they can expect their state pension to provide; help them avoid old-age poverty; and provide a bedrock on top of which private pension saving can be built. In order to achieve these goals, the guarantee has to be communicated coherently and transparently, and its implications have to be clear and understandable for both current and future generations of pensioners.

15. The four points are:

1. There will be a government target level for the new state pension, expressed as a share of median full-time earnings. Increases in the state pension will in the long run keep pace with growth in average earnings, which ensures that pensioners benefit when living standards rise.

2. Both before and after the target level is reached, the state pension will continue to increase at least in line with inflation every year.

3. The state pension will not be means-tested.

4. The state pension age will only rise as longevity at older ages increases, and never by the full amount of that longevity increase. To increase confidence and understanding, the government will write to people around their 50th birthday stating what their state pension age is expected to be. Their state pension age would then be fully guaranteed 10 years before they reach it.

16. To set the target level, as the government has done with the minimum wage, politicians should state what they believe to be an appropriate level for the state pension relative to average earnings. They should then legislate a pathway to meeting that target with a specific timetable. This would result in an explicit commitment from the government to target a level of state pension relative to average earnings – which may be above its current level – and the four-point pension guarantee would then maintain that value in the long run too.

1. Introduction

This report of the Pensions Review, led by the Institute for Fiscal Studies in partnership with the abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, considers the role of the state pension in the UK pension system. The UK state pension is an important feature of the UK’s broader welfare state, providing income to older individuals, most of whom are no longer in paid work. First introduced in 1909, and then overhauled in 1948 following the Beveridge Report, the state pension system has been subject to substantial reform each decade since the mid 1970s in response to demographic shifts, fiscal considerations, and changes in political and economic priorities (see Bozio, Crawford and Tetlow (2010) for a comprehensive review of the history of the UK pension system).

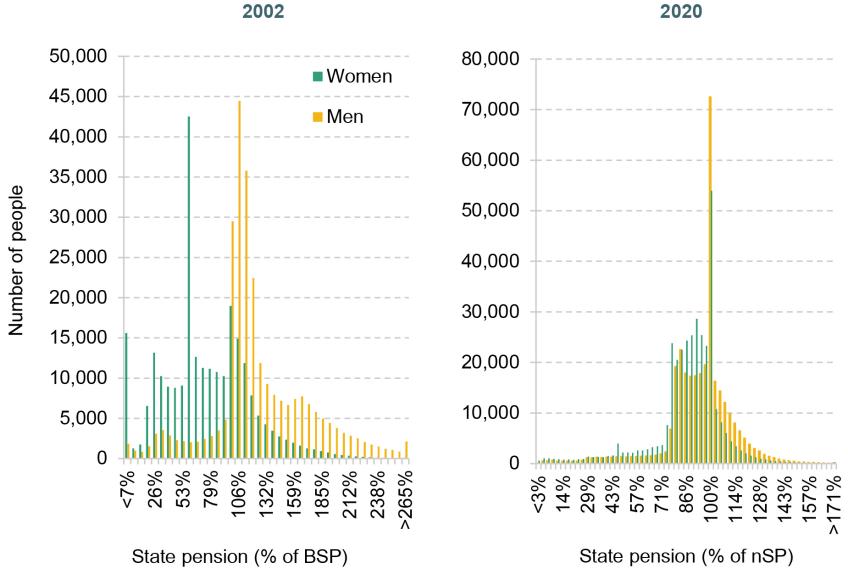

Today, the state pension system differs in important ways depending on the point at which an individual reached state pension age (SPA, the age at which the state pension can first be claimed). Those who reached this age before 6 April 2016 are typically entitled to the flat-rate basic state pension (BSP, full amount currently £156.20 per week). On top of this, many will also have some earnings-related state pension which they built entitlements for during working life. Those reaching the SPA on or after 6 April 2016 are typically entitled to the new state pension (nSP, full amount currently £203.85 per week), which is a flat-rate state pension higher than the BSP. 1

This means that, over time, the system in place since 2016 will become increasingly dominant for pensioners as older people (who reached the SPA prior to 2016) gradually die, and as those in subsequent generations become more likely to be entitled to a full nSP, and no more, when they reach the SPA.

While this report provides some background information on the historical evolution of the UK state pension, in our analysis and recommendations we focus on the nSP. In particular, we do not propose any additional changes to the benefits of those currently receiving the BSP or other state pensions – we simply assume that any changes to the nSP would apply in a similar way.2

State pension expenditure represents a significant portion of the UK government’s total expenditure – it is the second-most expensive item of public spending after the National Health Service (NHS). Figures from the Department for Work and Pensions (2023c), which relate to Great Britain, put total state pension spending at £124 billion per year in 2023–24, or 4.8% of national income. Including some other pensioner benefits (pension credit and winter fuel payment), this rises to £132 billion (5.1% of national income), while adding in all cash payments to pensioners – including disability benefits and means-tested support for housing costs – brings this up to £152 billion (5.9% of national income). On top of this, there is also further means-tested support for council tax bills, and of course those over the SPA also make relatively more use of many public services – not least the NHS and social care systems.

There are a number of challenges facing the UK pension system and public finances in the future, in particular in the context of significant demographic change. Rising longevity at older ages, and falling fertility, mean that the UK has an ageing population. The proportion of the adult population in receipt of the state pension is therefore increasing over time, which puts pressures on the fiscal sustainability of the system in the long run. This has been exacerbated by the poor economic performance of the UK economy since 2008. But it is also the case that most pensioners rely on the state pension to provide the majority of their income in retirement. In the current year, 2023, 12.8 million individuals across Great Britain receive an average of £187 per week from the state pension. While most would need a considerably higher income in order to preserve their working-age living standards through retirement, it is a sum that very few who are retired could do without. It is therefore imperative that we have a secure and sustainable state pension system that continues to serve its purpose of providing an important source of income throughout retirement for future generations of pensioners.

This report offers a broad range of new analysis that we have conducted on the UK state pension system, considering its current state and challenges facing it in the future. Throughout this report, we also present evidence on the public’s perception of the state pension system from polling and public engagement work which was specially commissioned for the Pensions Review by abrdn Financial Fairness Trust and conducted respectively by YouGov and Ignition House in the summer of 2023. Drawing on all this – and from discussions with our expert Steering Group (Alistair Darling, David Gauke and Joanne Segars), with three sets of Advisory Groups and with many others – we put forward reforms that would improve the current system and help ensure it will function well not just today, but also in the coming decades.

The report proceeds as follows. Chapter 2 introduces the UK state pension system in more detail and examines how the level of the state pension, and public spending on it, have evolved over time. Chapter 3 focuses on demographic change and its implications for the future of public finances. Chapter 4 discusses inequalities in state pension incomes and how they relate to eligibility rules. Chapters 5 and 6 analyse the key levers that the government has available within the current system to address public finance concerns: increases in the SPA and changes to state pension indexation, respectively. We also present evidence about how these changes affect different people. Chapter 7 concludes this report. These conclusions will feed into our final recommendations at the end of the Pensions Review.

2. Introduction to the UK state pension system

In this chapter, we first introduce the UK pension system and its key features. We then examine how the level of the state pension and public spending on it have evolved over time, and how its current level relates to the government’s measures of income poverty. We discuss how the UK pension system is structured and how that compares internationally with other high-income economies. We also discuss the public’s views of the state pension.

2.1 Key features of the UK state pension system

The state pension system went through a significant change in 2016. Those who reached the SPA before 6 April 2016 were generally entitled to the flat-rate BSP (full amount currently £156.20 per week). There was also an earnings-related state pension (mainly the State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme, SERPS, and the state second pension, S2P) towards which employees may have built entitlements during working life. However, the majority of employees opted out of building up entitlement to an earnings-related pension in return for a reduction in National Insurance contributions and they built up a private pension instead (known as contracting out). In contrast, those reaching the SPA on or after 6 April 2016 are typically entitled to the nSP (full amount currently £203.85 per week), which is a flat-rate state pension unrelated to earnings over working life and which – like the flat-rate BSP before it – individuals are not able to opt out of.

The introduction of the nSP in 2016 marked a significant shift, as it swiftly transformed the UK’s pension system from an earnings-related to a flat-rate system. This was a much sped-up version of the recommendation by the Pensions Commission of the mid 2000s (Pensions Commission, 2004 and 2005) and had broad consensus behind it across the political spectrum. This was a fundamental change, and one of its key aims was to simplify the pension system in order to make it more predictable and easier to understand for future beneficiaries (Department for Work and Pensions, 2013).

The nSP, like its predecessors, is not means-tested or earnings-tested (i.e. it is not directly reduced for people with earned or other private income), though it is subject to income tax. Eligibility depends on an individual’s National Insurance contribution and ‘crediting’ history, and not their income, wealth or work status. Entitlement to nSP is built through ‘qualifying years’. These qualifying years can be built up through either employment during which National Insurance contributions were made, receipt of National Insurance credits due to circumstances such as unemployment, incapacity, receipt of universal credit or certain formal roles as a parent or carer, or paying voluntary National Insurance contributions. Individuals with fewer than 10 qualifying years receive no state pension. Since 2016, those with 35 qualifying years are eligible for the full nSP; additional years beyond 35 do not add additional entitlement.

The state pension can be claimed once individuals reach their SPA, currently 66 for both men and women. The state pension cannot be claimed prior to age 66. Those not claiming the state pension at the SPA are deemed to have deferred and can receive a higher pension when they do claim it. With the new state pension, a deferral of one year increases the value of the state pension by 5.8%. But very few people do this – 95% of individuals receive the state pension within two months of reaching their SPA (Crawford and Tetlow, 2010), and as of September 2019, 8% of all state pensioners were in receipt of an ‘increment’ on top of their state pension entitlement as a result of having deferred their claim (Thurley, 2020)3 . While being in paid work does not affect eligibility to the state pension, Cribb (2023) shows that people still working in their late 60s are less likely to claim their state pension once they have reached the SPA.

Since 1975, governments have legislated for the state pension to increase automatically each year (though the default uprating is sometimes set aside to increase the state pension by more or less than the default). Most recently, since 2011 the BSP – and since 2016 also the nSP – has been indexed in line with the ‘triple lock’ mechanism. This means that each April, by default, the value of the pension increases by the highest of average earnings growth, inflation or 2.5%.4 As a result, the value of the nSP increases faster than earnings whenever earnings growth is lower than inflation or 2.5%. In periods of relatively stable macroeconomic conditions, we would expect average earnings growth to be higher than both inflation and 2.5%, meaning that in those periods the value of the state pension would increase in line with earnings (and faster than prices or 2.5%).

The period since the 2008 financial crisis has been one of dismal economic growth, during which earnings have often grown by less than inflation or 2.5%. Cribb, Emmerson and Karjalainen (2023) show that over the 13 years between 2011 and 2023, the state pension rose by earnings growth just three times, by inflation six times and by 2.5% four times5 . This mechanism ratchets up the value of the nSP relative to both earnings and prices over time, as any increase relative to prices or earnings is locked in for all future periods.

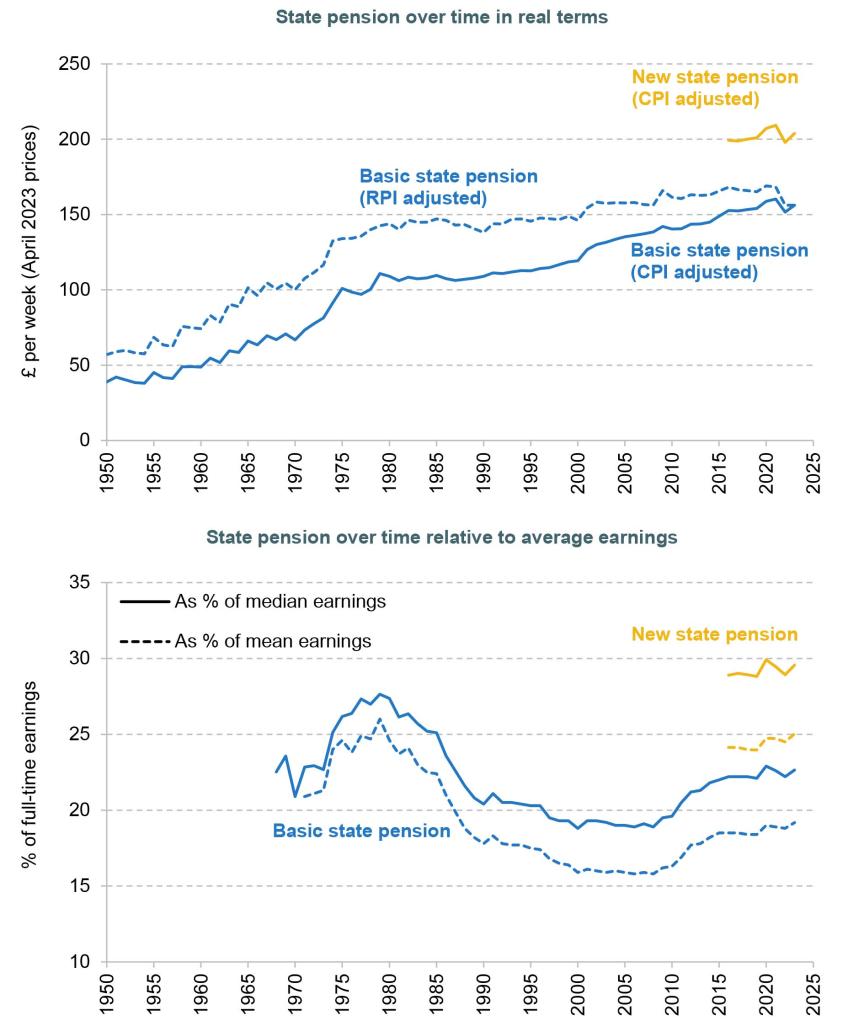

The triple lock is often discussed in the media, and indeed indexation of the state pension has been a contentious topic in the UK since at least 1980 when then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher announced that the state pension would, by default, be price indexed rather than increased each year by the greater of growth in prices or earnings, as had been the case since 1975. Figure 2.1 shows the value of the BSP and nSP over time. The top panel shows the value in real terms from 1950 to 2023, where the BSP has been adjusted for the Consumer Prices Index (CPI, which gives a measure of inflation that the Bank of England started targeting in 2003 and that has become particularly widely used since the early 2010s) and for the Retail Prices Index (RPI, which gives a longer-running measure of inflation, but a flawed one that tends to overstate inflation). The bottom panel shows the value of the BSP and nSP relative to average (mean and median) full-time earnings.

Figure 2.1. Value of the state pension entitlement over time in current prices (real terms) and as a share of average earnings

Note: Median full-time earnings since 1984 are from DWP benefit rate statistics; values for earlier years are calculated using the growth rate of nominal full-time median earnings from the Family Expenditure Survey (FES). Mean full-time earnings are from DWP benefit rate statistics. The 2023 values are calculated using the April 2022 to April 2023 growth rate of average weekly earnings (total pay) reported by the Office for National Statistics.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/abstract-of-dwp-benefit-rate-statistics-2022 and authors’ calculations.

First focusing on the top panel, over the period from the 1950s to the mid 1970s – where indexation of the state pension was done on an ad hoc basis – the value of the BSP increased much faster than prices. As stated above, the earnings indexation that had applied to the BSP in the mid 1970s was replaced in 1980 with price indexation (based on RPI). Over the next three decades, the state pension was stable in real terms when adjusted by RPI and rising in real terms when adjusted by CPI (which is typically lower than RPI). Under the triple lock, the value of the BSP – and more recently the nSP – has continued to increase in real terms.6

While the state pension was stable or rising in real terms, its level relative to overall living standards in the economy fell during the period of price indexation, as illustrated in the bottom panel of Figure 2.1. (The solid line shows the value of the state pension relative to median full-time earnings and the dashed line shows its value relative to mean full-time earnings.) In periods of relative economic stability, we generally expect earnings to rise faster than prices, as was the case in most years from 1980 to the late 2000s. As a result, the value of the BSP fell relative to earnings over this period, especially during the 1980s when earnings growth was particularly strong.

This decline in the value of the BSP relative to average earnings was recognised by the Pensions Commission in the mid 2000s, and it recommended a return to earnings indexation (though, unlike in the 1970s, this was not a ‘double lock’ – i.e. if earnings grew less quickly than prices, the proposal was that the value of the BSP would fall in real terms). This was then legislated – with cross-party support – with an intention for it to come into effect from 2012 and a firm commitment for it to happen by 2015. However, before earnings indexation was introduced, the coalition government introduced the current triple lock. With the introduction of the nSP and (to a lesser extent) the triple lock, the value of the flat-rate component of the state pension today – at close to 30% of median full-time earnings – is above the level that the BSP was at relative to earnings in 1980 (when the ‘earnings link’ was broken). It is also the highest level since 1968, the first year of our data.

2.2 Spending on the UK state pension

The UK state pension operates on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) basis. This means the state pensions of current pensioners are paid out of current general tax revenue (which is disproportionately, but not entirely, paid for by current generations of working-age people). The expectation – of course – is that taxation raised (disproportionately) from the next generation of working-age people will pay for the state pensions of the current generation of workers, and so forth. While qualifying years which determine eligibility for the state pension can be built up based on whether an individual has paid National Insurance contributions (but also in other ways, as discussed in Chapter 4), there is no ‘pot’ into which these National Insurance contributions are paid that is then invested in order to pay for that individual’s pension in the future – contrary to popular belief. Rather, the National Insurance contributions and other taxes levied in any given year help to pay for government spending in that year.

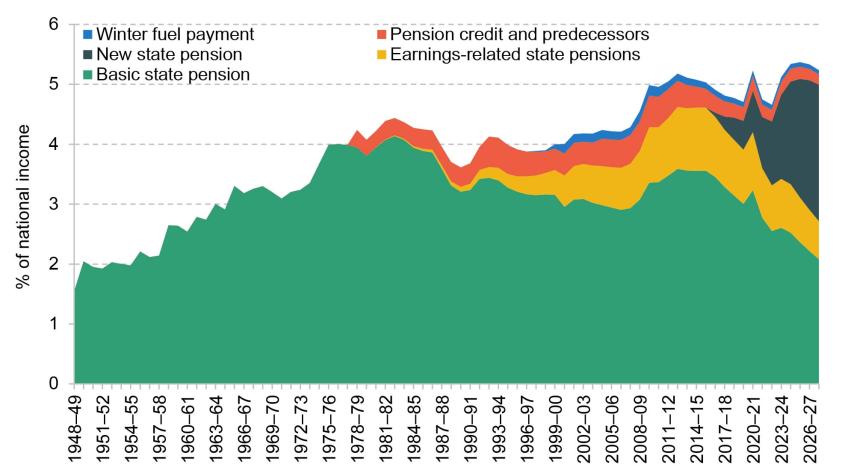

Figure 2.2 shows spending on the state pension, as well as associated pensioner benefits (pension credit and winter fuel payment) over time as a share of national income. First, looking at overall spending on the state pension, we can see that spending has increased from around 2% of national income in 1948–49 to just below 5% currently. Spending on the state pension rose consistently as a share of national income from the 1940s to the early 1980s, then fell in the 1980s and remained broadly flat until the financial crisis, as the value of the BSP fell relative to average earnings (as shown above). After the financial crisis, spending as a share of national income then rose to around its current level.

Figure 2.2. Spending on state pensions and pensioner benefits as a share of national income

Note: Spending relates to Great Britain.

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, 2023c.

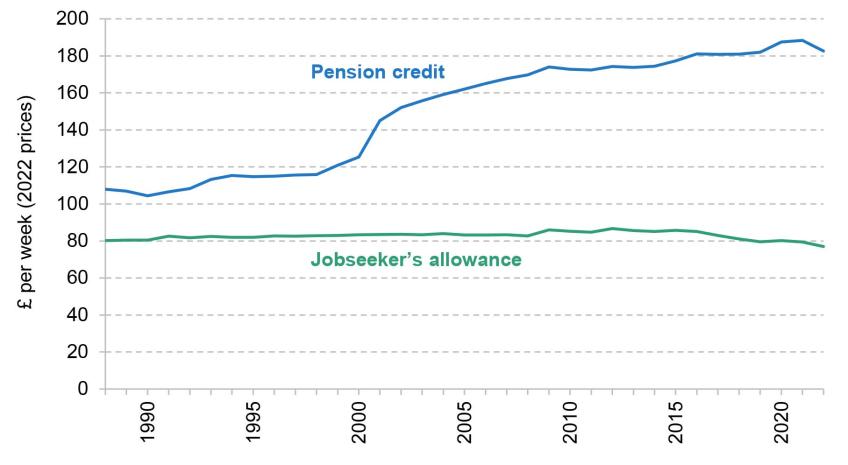

While pensioner benefits are not the focus of this report, we can also look at how spending on those has changed over time. Pension credit is a means-tested benefit that can be claimed by those whose income is below a minimum level (in 2023–24, this is £201.05 per week for a single pensioner and £306.85 per week for a couple where both are over the SPA)7 . Winter fuel payment makes payments of £200 per household (£300 for households where the members are aged 80 or over) in the winter to most pensioner households. Spending on these additional benefits has become relatively less important over time with, in particular, those reaching the SPA from April 2010 and (especially) April 2016 having greater entitlements to the flat-rate state pension, which reduces eligibility for means-tested support. Spending on winter fuel payment, while £2.0 billion in 2023–24, has always been small relative to the support provided through the state pension. Overall spending in the coming year, 2024–25, is forecast to be 5.3% of national income, which would be its highest share of national income ever.

There are no predefined rules in the UK to adjust pension system parameters in response to shifts in demographic, economic or financial indicators. In other words, unlike in some other countries, the UK state pension system does not adjust automatically to changing circumstances. For example, the state pension age in Denmark will rise beyond 68 (which it will reach in 2030) one-for-one in line with rising life expectancy (OECD, 2019), while the amount of support provided through Sweden’s state pension is linked directly (and negatively) to the longevity of the previous generation. Instead, in the UK, any changes to indexation, eligibility and the SPA (or other parts of the formula that determines entitlements) have been ‘manually’ enacted through legislation over the years. This requires governments to be proactive and to take a long-term view. For example, reforms legislated under Conservative governments in the 1980s and 1990s and the increases in the SPA legislated under Labour in the 2000s and then the coalition government in the 2010s often delivered – or will deliver – reductions in spending that did not occur until a later (and often much later) parliament.

2.3 Structure of the UK state pension system

It is worth noting that a flat-rate pension is by no means the only possible way to structure a state pension. The key alternatives to the current flat-rate system would be to have a means-tested state pension, like the Australian ‘Age Pension’,8 or an earnings-related scheme, as many European countries and the United States operate.

Means-testing pensions can help target support to the most financially vulnerable pensioners, instead of providing income to those with significant sources of other income. The clear attraction of means-testing is that it can allow more resources to be transferred to lower-income pensioners at a lower overall budgetary cost in a given year. But it has a number of potential drawbacks. One is that take-up of these benefits is not complete, meaning that some fall through the safety net. Another is that means-testing reduces incentives for individuals to save privately for retirement; means-testing of pensioner support essentially reduces the return that some can expect on their private pension saving. The lower the means-testing threshold, the greater the extent to which government spending is targeted at low-income pensioners, but the more widespread this issue of distorted incentives would also be. In Australia, this disincentive is mainly avoided because of the existence of compulsory saving into a private pension ‘Superannuation’ scheme. Means-testing of the state pension could also reduce work incentives, most obviously for those above the SPA who might be considering continuing in some paid work.

With an earnings-related pension, the pension amount an individual receives is linked to their past earnings. In 1975 the UK passed legislation introducing the State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme (SERPS). This was intended to provide a substantial earnings-related pension to most employees who did not have access to an occupational pension from their employer. Entitlements depended on earnings in each financial year, and under the initial SERPS formula were based on the highest 20 years of an individual’s earnings. But the full eventual impact on public spending was not forecast at the time (Hemming and Kay, 1982). Legislation in the mid 1980s halved its future cost and further legislation in the mid 1990s halved it again. The rising cost of SERPS may also have been a factor in why price indexation of the BSP was retained for so long after 1980: as can be seen in Figure 2.2, overall public spending on support for pensioners did not fall between 1980 and 2010 despite the generosity of the BSP falling sharply relative to average earnings (as shown in Figure 2.1). The nSP will deliver the final demise of SERPS relatively rapidly as each successive generation reaching SPA from April 2016 will have reduced entitlement to SERPS.

There are good arguments for the state providing an earnings-related pension. Individuals will typically want to have a secure income through retirement at a level that provides a standard of living comparable to what they had during their working life, and for a number of reasons there can be considerable challenges in a private pension system delivering this. But an earnings-related pension means that a large share of state pension would go to those who had previously been higher earners, implying either a lower state pension for those who have been low earners or higher public spending on state pensions targeted at the better-off (though better-off individuals will, of course, also have paid higher taxes over their working life).

We do not sense a widespread political appetite for either a lower state pension for low earners or higher public spending, and it would be difficult to describe the UK’s previous attempts at earnings-related state pensions as ones that successfully delivered retirement income security. All in all, the UK’s experience with an earnings-related state pension has been an unhappy one. Given where we are, we do not suggest another attempt to introduce one. A flat-rate approach would also be in keeping with the vision of Sir William Beveridge, the architect of the UK’s post-war welfare state, and the recommendations of Lord Turner’s mid-2000s Pensions Commission which were endorsed across the political spectrum.

2.4 Level of the new state pension

An obvious question for a flat-rate state pension is the level at which it is set. With an earnings-related pension, the level may be set as a replacement rate, i.e. a percentage of some measure of pre-retirement earnings that the state pension should cover for someone with a full working life. But with a flat-rate pension, the rate will have to be set differently (as the cash amount is by definition the same for all people who have enough qualifying years). In particular, the new flat-rate pension can be thought of as providing a foundational layer or ‘first pillar’ upon which individuals can build retirement income through private pensions and other saving. There are other initiatives that aim to set out what the minimum income for retirees should be from all their income sources (for example, see Finch and Pacitti (2021) or the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association’s Retirement Living Standards9 ). However, we will not compare the state pension directly to those levels, given that the state pension is intended to act as a basis for further private saving, rather than necessarily an adequate level of income on its own.

Ideally, for the nSP to support people’s private pension saving effectively, it is important that people have a reasonable idea about the level of the state pension. This way, people can make an informed decision about private pension saving based on how much income they might be able to expect from public provision.

Despite the relative simplicity of the new state pension system, it seems that working-age people have a low level of understanding of the state pension. Polling commissioned for this Pensions Review in the summer of 2023 and published in Barker, Cribb and Emmerson (2023) showed that only 13% of 25- to 49-year-olds and 31% of 50- to 64-year-olds answered that the current value of the new state pension (£203.85) was between £180 and £220. This shows that more needs to be done to inform the general public about the level of the state pension in order to assist individuals with their retirement planning.

Many also argue that the level of the new flat-rate state pension should be set in a way that protects people from income poverty. Indeed, that was a key intent of the original Beveridge Report – which proposed that the BSP should be set so that those receiving the full amount were free from poverty. While income poverty lines, which determine whether people are categorised as being in (or not in) income poverty are inherently arbitrary, they are useful for assessing living standards of pensioners. To determine whether the nSP achieves Beveridge’s target, we therefore assess its current level against the government’s relative income poverty line (measured as 60% of contemporaneous median disposable income, adjusted for household size and after deducting rent and certain other housing costs).

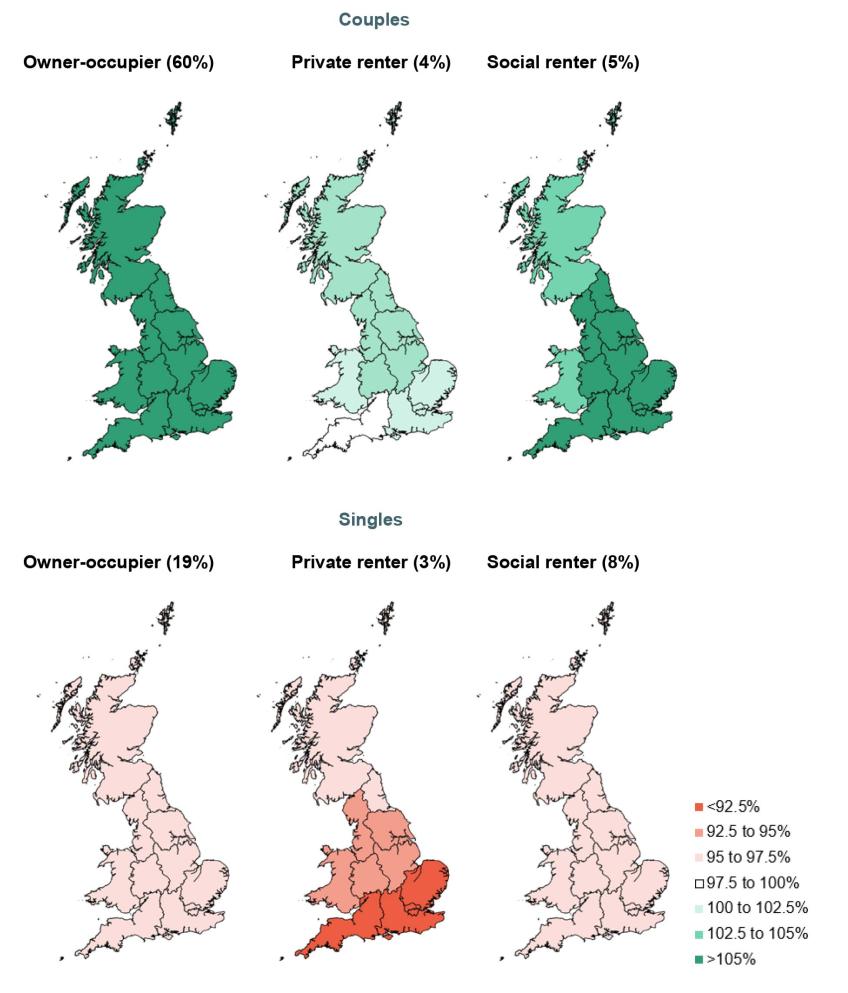

We want to understand how incomes under the current state pension system compare with poverty thresholds, as this is what most current workers (and future retirees) will, under current policy, be eligible for: DWP modelling shows that more than 80% of those reaching the SPA by the mid 2030s will be eligible for the full nSP (Department for Work and Pensions, 2013). An analysis of current pensioners’ incomes is less informative, because the amounts that current pensioners are entitled to will still reflect entitlement rules of previous state pension systems. In particular (and will be discussed in Section 4.1), those who reached the SPA prior to April 2016 are not eligible for the nSP and those who reached the SPA prior to April 2010 were much less likely to qualify for a full BSP.10

The maps in Figure 2.3 illustrate how income provided by a full nSP, alongside any means-tested housing-related benefits (council tax support and housing benefit), compares with the relative after-housing-cost income poverty threshold. We create a number of ‘example households’ with different housing tenures for different parts of Great Britain11 with one or two 66-year-old residents in the current tax year (2023–24). We assume that each individual receives a full nSP, winter fuel payment, and council tax support and housing benefit where applicable, but no additional benefits such as disability benefits. For social renters, we assume their rent is the local authority average for that region. For private renters, we assume their rent is the 30th percentile for a one-bedroom home for that area. Importantly, we assume these households receive absolutely no private income (such as from earnings, private pensions or investments).

Figure 2.3. Income after housing costs for those with a full nSP and no private income, as a percentage of the relative poverty threshold (% of current 66- to 70-year-olds in each group in parentheses)

Source: Authors’ calculations using the IFS personal tax and benefit model, TAXBEN, based on example households of 66-year-olds. It is not currently possible to include Northern Ireland in these calculations.

The shading on the maps indicates how the income (after deducting housing costs) of the example families in each area compares with the relative income poverty threshold. The percentage figure in parentheses at the top of each map is the share of current 66- to 70-year-olds who are of that housing tenure and marital status.

Starting with couples, it is clear that with two nSPs and any means-tested benefits they are entitled to, and even without any private income, all of the example households have incomes at or above the relative income poverty threshold.12 For owner-occupiers, which is by far the most common housing tenure among couples in their late 60s, incomes are more than 20% above this threshold. Incomes for social renter couples are 4–5% above the threshold.

For single-person households, the picture is different. Single owner-occupiers and single social renters – who together comprise the vast majority of single individuals in their late 60s – are just below the relative income poverty threshold with incomes of roughly 95% or 97% of the threshold depending on region (in pound terms, this is equivalent to £10 or £7 per week less than the threshold, respectively). However, single private renters are households for whom the nSP and means-tested benefits alone will often leave them further below the relative income poverty threshold. For households in the North East of England, the after-housing-cost income from the nSP and housing-related means-tested benefits is roughly 96% of the poverty threshold. For those in the South West, the after-housing-cost income is below 90% of the poverty threshold.

These regional differences in how far below the poverty line these households fall are due to the fact that housing benefit rates for those in private rented accommodation have been frozen in cash terms since April 2020. This means that when private rents increase, the maximum housing benefit people can claim does not keep pace. While there are differences in the percentage increase in rents between regions over this period, the largest driver for the size of the shortfalls between the poverty line and the after-housing-cost incomes for these example households is the differences in how much private rents have increased in cash terms, which are driven by the initial (April 2020) rent levels. Even if the percentage increase in rents has been the same across areas, the pound difference in housing costs that are not covered by the housing benefits will be larger in areas that had higher rents to begin with. This is what drives the South–North divide for the private rented sector in Figure 2.3.

The Chancellor announced in the Autumn Statement in November 2023 that the cash freeze on the local housing allowance (LHA) rates, which set the maximum amount for housing benefit available, would end from April 2024. From April 2024, the LHA rates will be updated to the level of the 30th percentile local market rents. Our modelling assumes that rent levels in the private rented sector are exactly at the 30th percentile of rents for the local area, which means that the announced increase in the LHA rates fully removes the shortfall between private rents and housing benefit available in this analysis. This change will make the private renter households look like social renters, whose rents are always fully covered by housing benefit. However, this uprating follows four years of cash freezes on LHA rates, and indeed, in any years when the LHA rates are frozen in cash terms, the gap between private rents and housing benefit will open up again even in our simple analysis. Using households with private rents exactly at the 30th percentile for the local area is also a simplifying assumption, and many households will be paying private rents that are above the LHA rates even after the change.

It is worth keeping in mind that out of current 66- to 70-year-olds, only 3% are single private renters. However, trends in the housing market indicate that this proportion will rise significantly over the next decades. While it is difficult to assess exactly the extent to which current younger generations will be able to purchase (or inherit) their homes by the time they retire, it is likely that as the prevalence of private renting among pensioners increases, this will also have implications for housing benefit receipt and spending. The pensioner benefit system outside of the state pension will be discussed in more detail in a separate future report; but a potential implication of Figure 2.3 is that a well-targeted way of reducing pensioner poverty could be to increase the generosity of housing benefit for pensioners living in private rented accommodation.

As people move through retirement, many more become single-person households when their spouse or partner dies before them. We also know from differences in mortality rates that individuals from poorer households, especially men, have on average higher mortality rates, meaning that lifetime-poor women are more likely to spend more of their retirement as a single-person household.

While relative income poverty is a key indicator that is used to measure the extent to which households may struggle to meet basic needs, it is only one potential measure to judge the new state pension and pensioner incomes against. It is likely to be difficult for a household living at, or only a little way above, the relative income poverty line to build up any rainy-day savings, which would make it difficult for those households to deal with any unexpected costs such as replacing durable goods, other repairs or large unexpected rises in living costs. However, this analysis has also assumed that these households have absolutely no other sources of income apart from the state pension. Especially since the introduction of automatic enrolment into private pension saving in 2012, most future pensioner households are likely to have at least some private pension savings in addition to the new state pension.

While this illustration shows that the nSP and means-tested benefits are enough to keep most households above the relative income poverty threshold, we also know that the relative income poverty rate (after housing costs) among pensioners in the most recent year of data (2021–22) was 18% (Ray-Chaudhuri et al., 2023). There are a number of reasons why the current pensioner poverty rate is higher than indicated by our illustrative example. First, those who reached the SPA before 6 April 2016 are not eligible for the nSP. Many older pensioners, especially women, receive much smaller amounts than the current full rate of the nSP. And even those who reached the SPA on or after 6 April 2016 may not receive the full nSP, if they do not have the 35 qualifying years needed for entitlement to the full amount. There are also many pensioners who are in a couple with a person who is still below the SPA, and if that person does not receive earnings or other private income, a single state pension may not be enough to get the household above the poverty threshold. Some people may also not be eligible for means-tested benefits – for example, due to having assets above £16,000. Even among those who are eligible for means-tested benefits, take-up rates are low. It is also possible that the pensioner poverty rates derived from survey data somewhat overestimate the true poverty rate, as it is well known that receipt of means-tested benefits is under-reported in household survey data. Finally, for private renters, we have assumed that people live in a property with a rent that is equal to the 30th percentile of rents in the area, whereas some may live in more expensive private rented accommodation.

2.5 The UK in international context

In order to understand the UK pension system better, it is also useful to examine how it compares with other countries’ systems. We first consider how the balance between public and private provision differs between countries, and then move on to assess how replacement rates and retirement ages differ. We focus on comparison with a set of larger high-income countries, and include Australia, Ireland, the Netherlands and New Zealand as they have more similar pension systems to the UK, with a significant role for private pension provision, as is shown below.

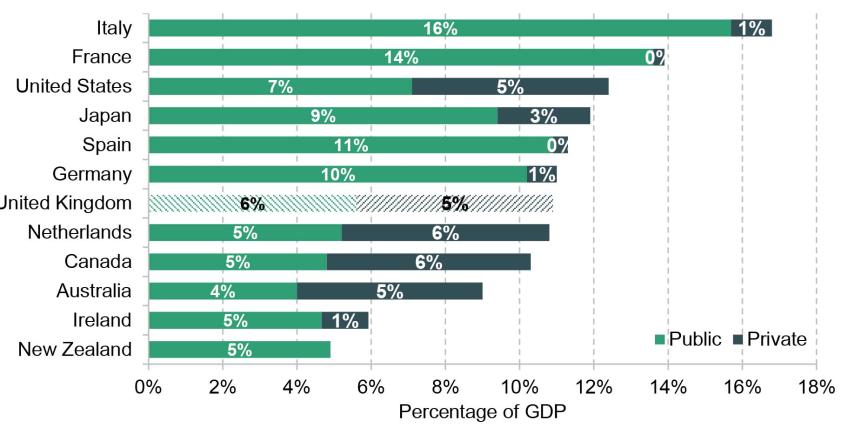

The UK pension system consists of a (now) flat-rate state pension, and semi-voluntary private saving (due to automatic enrolment of most employees earning more than £10,000 a year into a private pension). Figure 2.4 shows state and private pension expenditure, as a share of national income in 2017, for the UK and other developed countries.

Figure 2.4. Public and private pension expenditure as a share of national income, 2017

Note: Numbers for Ireland are expressed as a percentage of GNP as Irish GDP is 26% higher than GNP due to income received by multinationals.

Source: Tables 8.3 and 8.4 of OECD (2021).

The first thing to note about this figure is that there is variation in the level of total public and private expenditure on pensions between countries, where public expenditure refers to public spending on pensions and private expenditure refers to payments from private pension schemes. Among these countries, the level of public and private spending on pensions varies from 5.9% of national income in Ireland to 16.8% of national income in Italy. The UK is in the lower half at 10.9%. This variation in spending on pensions may be created by a number of factors, perhaps most obviously differences in the age structure of the population. But it will also be driven by different parameters of the system – namely, the generosity of the state pension and the age at which it can be claimed.

In addition to the level of total expenditure on pensions, we can also focus on the split between public and private pension expenditure. It is clear from the figure that the public pension system in most countries plays a much more important role than in the UK, whereas the UK system relies much more on employer and individual contributions to private pensions, which are tax advantaged. Expenditure on state pensions in the UK was 5.6% of national income, with expenditure on private pensions not far behind at 5.3%.13 In most other large Western European countries (Italy, France, Spain and Germany), pension expenditure and thus income is nearly exclusively the responsibility of the state.

There are countries where the balance between public and private spending in the pension system aligns more closely with the UK. This includes the Netherlands and – with the exception of Ireland – the English-speaking countries shown in Figure 2.4 (the United States, Canada and Australia). However, there are some key differences between the UK and these countries. For example, the US public pension scheme (known as ‘Social Security’) is an earnings-related scheme and provides more income (at 7.1% of national income), whereas income from private pensions is around that in the UK. In Australia, where spending on private pensions exceeds that on public pensions, state pension benefits are means-tested and private saving is compulsory for the vast majority of workers.

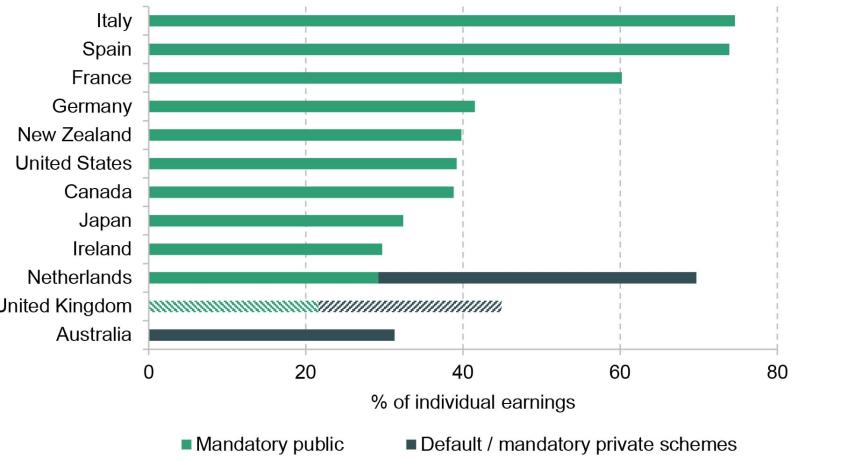

We can also use pension ‘replacement rates’ in order to assess the generosity of the different systems. A pension replacement rate is a measure that takes the average pre-tax pension entitlement and divides it by average pre-tax pre-retirement earnings. It measures to what extent a pension system provides a retirement income to replace pre-retirement earnings.

Figure 2.5 reproduces OECD calculations of pension replacement rates for an employee on average male earnings, and illustrates that the UK gross replacement rate provided by the public pension alone is low by international standards. In our selected set of countries, only Australia has a lower rate (due to having a means-tested public pension), though the UK looks similar to Ireland on this dimension. However, as discussed above, this is partly because of a different balance of public and private sector saving. When considering automatic enrolment as a form of quasi-mandatory saving (as the OECD does, and which reflects the fact that around four in five of all employees are saving in a workplace pension (Office for National Statistics, 2022a)), the UK’s overall replacement rate is higher than that in many other major economies, and below only Italy, Spain, France and the Netherlands. The OECD considers as ‘quasi-mandatory’ any schemes where active choice by the employee is not required and employees will by default save into a private pension scheme (even if opt-out is available).

Figure 2.5. Gross replacement rates from mandatory public and private pension schemes for a mean male earner, by country

Note: Public pensions in Australia are means-tested, which means that for a middle earner the public replacement rate is zero. The UK’s automatic enrolment system is here considered a mandatory private scheme. In calculating replacement rates from mandatory private schemes, the OECD assumes a real rate of return of 3%, real earnings growth of 1.25%, inflation of 2%, a real discount rate of 2%, defined contribution conversion rate of 90% and labour market entry at age 22 in 2020. The OECD revised the private scheme replacement rate for the UK down by 4.1 percentage points after the publication of the 2021 report, in order to take account of the floor to contributions for the workplace private pension, which were mistakenly excluded when calculating the results in the main publication.

Source: Table 4.2 of OECD (2021).

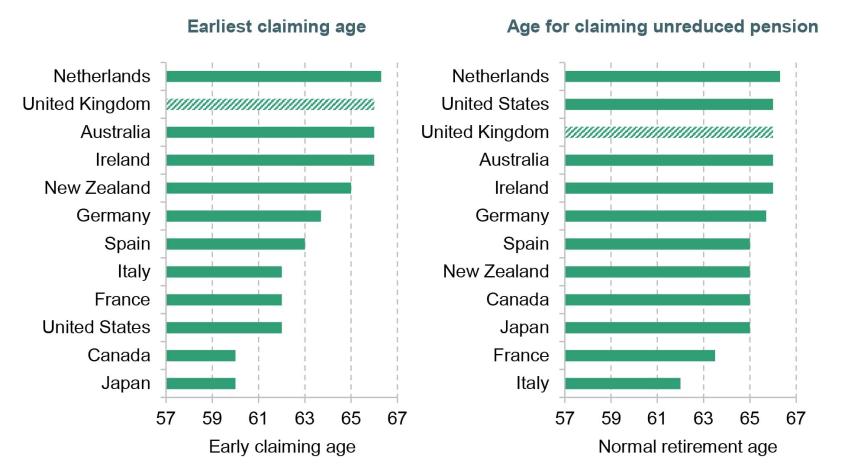

Another key parameter of the state pension system that will affect spending on state pensions is the age at which individuals can claim a state pension. The UK has one age – the SPA – from which point on the pension can be claimed in full. In many other countries, there are two distinct ages – an ‘early retirement age’, at which point individuals can first draw their state pension, albeit at a lower rate. The ‘normal retirement age’ is then the age at which individuals can first draw a full public pension. Having a single age means that essentially the SPA is both the early and normal retirement age. The left panel of Figure 2.6 shows that, compared with other countries, the early retirement age in the UK is relatively high. On the other hand, the right panel of the figure shows that there is less variation among countries in the normal retirement age; while the UK is still in the upper half in the figure, many other countries also have a similar age for claiming an unreduced public pension. The notable exceptions are France and Italy, which were the two countries in Figure 2.4 with the highest levels of public pension income.

Figure 2.6. Pension claiming ages for individual retiring in 2020

Note: Assumes an uninterrupted career from age 22.

Source: Table 3.5 of OECD (2021).

2.6 Public views

The state pension is, and has been for decades, an integral part of the UK’s welfare state. The quote below from public engagement work commissioned as part of this Pensions Review in the summer of 2023 illustrates this sentiment among the public.

‘[The state pension has] always been there and is part of the country’s DNA; as is the NHS. People need structure in their lives and to feel that the Government has their back when it comes to their working life, if they get ill, and retirement.’

Male, aged 60–78

However, as illustrated in Figure 2.4 above, the UK’s pension system differs from many other European countries’ systems in that individuals and employers carry much more responsibility in saving for retirement. An interesting question therefore is to what extent the public’s views are aligned with this approach.

Polling commissioned for this Pensions Review in the summer of 2023 shows that when working-age people were asked who they think have ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ of responsibility to ensure people retire with a reasonable standard of living, 85% responded ‘individuals and their families’, 84% responded ‘government’ and 78% responded ‘employers’ (Barker, Cribb and Emmerson, 2023). This suggests that people seem to agree that it is not just the government’s responsibility to ensure an adequate standard of living in retirement, and that individuals, their families and employers share in that responsibility.

On the other hand, in a system where individuals carry more responsibility for ensuring adequate standards of living in retirement, it is important that people feel confident in their knowledge and understanding of the system, in order to allow them to make informed decisions on how much saving they will need to do privately on top of the public pension.

However, there appears to be widespread confusion and indeed mistrust when it comes to the state pension system, and some of this may come from lack of knowledge. The quotes below from public engagement work commissioned as part of this Pensions Review in the summer of 2023 show that there are working-age individuals who do not feel comfortable with their level of knowledge of the pension system. In particular, they feel that their educational background and lack of guidance on pensions is a barrier in even trying to gain understanding. This potentially highlights the value of financial education and giving people, including young individuals, clear information on the features of the UK pension system.

‘I’m only 32 years of age. I don’t remember being taught about how to go about your pension in school. I don’t think in school they actually prepare you for what real life is all about. And going back, my parents never really spoke to me about it.’

Female, aged 30–49

‘Personally I find it quite difficult. I don’t have a lot of certainty of the future. I’m just not educated enough.’

Female, aged 18–29

2.7 Summary

Although by international comparison the UK pension system relies less on state provision and more on income from private pensions, the state pension is a very important part of the UK pension system and welfare state more generally, with around 5% of national income currently being spent on state pensions. The state pension system has been through a number of radical changes over time. In a rather roundabout way, overall these changes have led to simpler and much more uniform outcomes – in future, individuals will receive the full amount of the flat-rate pension from a single same age. Currently, the state pension is set at a level that means most households receiving a full new state pension have an income above the poverty line, even if they have no other income. But single private renters with no private income are at particular risk of having a low standard of living through retirement. Despite the system becoming simpler over time, very few working-age individuals know what the level of the new state pension is, and some feel that they lack the necessary education and advice to enable them to engage with the system.

3. Demographic change and future public finance challenges

In this chapter, we move from describing the current system to discussing future trends affecting the state pension system, in particular changes in demographics – including a comparison with other countries. We discuss what these mean for projected government spending, and the uncertainty associated with these projections. We also look at the public’s views of the future sustainability of the UK’s state pension system.

3.1 Demographic change

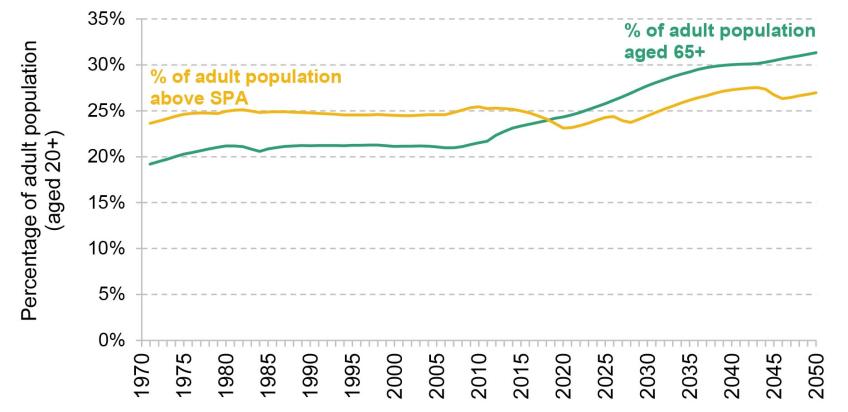

The age structure of the UK population is projected to change substantially over the next few decades. Figure 3.1 shows the fraction of adults (aged 20+) who are aged 65 or above, and the fraction over the SPA (which is currently 66 for both men and women, but as recently as 2010 was 60 for women and 65 for men). The share of the adult population aged 65 or above was relatively flat, between 21% and 22%, for the period 1977 to 2012, but rose from 22% to 24% between 2012 and 2020, and is projected to rise to 31% by 2050.

Figure 3.1. Percentage of the adult (aged 20+) population who are aged 65 or over, or aged above SPA, 1971 to 2020 (out-turn) and to 2050 (projected)

Source: Figure 13 of Cribb, Emmerson, Johnson et al. (2023).

Despite this rising share of the population aged 65 and over, the share of people above the SPA has so far remained remarkably constant because of the large increases in the SPA for women since 2010. However, despite further increases in the SPA – to 67 by 2028 and 68 by 2046 for both men and women – already legislated, the fraction of people above SPA is currently projected to increase from 24% in 2023 to 27% in 2050. Together with population growth, this means that by 2050 the number of individuals above the SPA will be 25% higher than today.

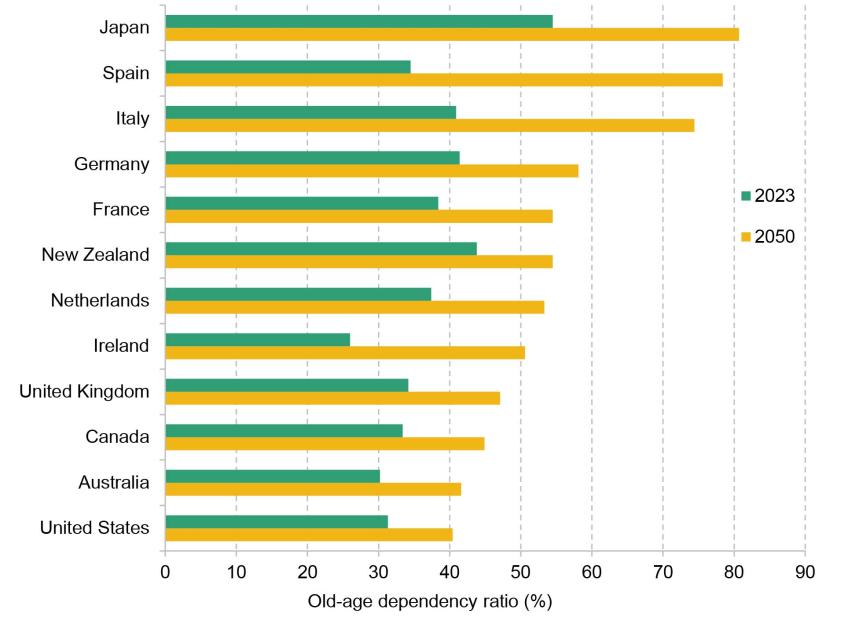

It is also interesting to know how the UK’s ageing population challenge compares with that in other countries. Figure 3.2 compares the old-age dependency ratios (the number of people aged 65 and over per 100 people aged 20–64) in 2023, and projections for 2050, for the same selected countries as considered in Chapter 2. On this measure, the UK’s old-age dependency ratio is currently relatively favourable, at least compared with many of the other countries, and that is projected to remain the case. While it is projected to rise substantially from 34% to 47% over the period, this would still mean that the UK’s old-age dependency ratio in 2050 is lower than for many other countries at that point – for example, Japan is expected to reach an old-age dependency ratio of 81% by 2050, and these figures are 55% for France and 58% for Germany. In fact, Japan already has an old-age dependency ratio above the UK’s 2050 forecast of 47%, at 55%. Countries with higher fertility and/or immigration, such as the United States, Canada and Australia, have lower projected increases in the dependency ratio (and lower projected dependency ratios in 2050). It is worth bearing in mind that these projections are based on current data, and future economic and social trends around fertility and life expectancy, as well as policy changes on immigration, could significantly alter how demographics turn out relative to these projections.

Figure 3.2. Old-age dependency ratios (number of individuals aged 65 and over per 100 people of working age) in selected OECD countries in 2023 and 2050

Note: Working age defined as those aged 20–64. Ranked by dependency ratio in 2050.

Source: OECD, 2023.

3.2 Public finance challenges

As shown in Figure 2.2, spending on state pension and other pensioner benefits has risen as a share of national income since the early 1950s. This is despite increases in the SPA and reflects increases in the generosity of the state pension relative to average earnings, the size of different cohorts above SPA, and increasing longevity at older ages for each successive generation.

Demographic change that increases the old-age dependency ratio over time presents a challenge for the public finances. Figure 3.3 shows that public spending on the state pension and other pensioner benefits combined (including winter fuel payment and pension credit, as well as other cash transfers such as attendance allowance, disability living allowance and housing benefit paid to pensioners) is projected to increase from the current 5.9% of national income to 7.6% by 2050–51. This increase of 1.7% of national income is equivalent to £45 billion per year in today’s terms. While demographic change is a key driver of the increase in spending, our calculations show that £24 billion of this increase is due to the triple lock pushing up the value of the state pension over time relative to earnings. On the other hand, the increases of the SPA to 67 and 68 limit the rise in spending in later years of this forecast period.

Figure 3.3. Projected spending on state pension, pensioner benefits, health and social care

Note: ‘Pensions’ includes winter fuel payment and pension credit. ‘Pensioner benefits’ is all other benefits paid to people above the SPA (such as attendance allowance, disability living allowance and housing benefit).