How much flexibility over hours does the NHS offer new mothers returning to work?

Three-quarters of NHS staff are women. This includes 90% of nurses and midwives, 48% of all doctors and more than half of all doctors aged under 50. Most of these women will have children at some point during their careers. Even before the pandemic, the NHS was experiencing high vacancy rates and the government has a target of increasing the supply of nurses by 50,000 by 2025. Attracting and retaining women who have young children, or are planning to have children, will be an important part of addressing current staff shortages.

In a report out today funded by the NIHR Health and Social Care Workforce PRU, we use payroll records from NHS England to examine the rates of retention and contracted working hours of nurses/midwives and doctors/dentists returning from maternity leave. This question is important for reasons of both efficiency and gender equality, to address widespread staffing shortages, to ensure the best use of talent, and to promote equal opportunities in medical and nursing careers. Employment practices in the NHS also have implications for the wider labour market, as the NHS is the largest single employer in England. The organisation therefore often acts as a competitor employer and helps shape broader employment norms.

We show that working part-time after maternity leave is the norm for both nurses and doctors. This indicates that the NHS is offering flexibility that is likely to contribute to high rates of retention after maternity leave. We do however find substantial variation in contracted hours across NHS trusts and medical specialties, which may indicate that not all those returning from maternity leave have the same access to reduced hours contracts.

We use NHS payroll records from England for the period between January 2014 and March 2020, and include all those directly employed by the NHS in the acute (hospital) and community sectors, including GPs in training. We do not have information on those who work in other sectors, and therefore we do not include fully qualified GPs and nurses working in primary care. We also do not have sufficient data on other forms of parental leave, such as paternity leave. Over the six years we observe, we observe 66,000 nurses/midwives and 16,000 doctors/dentists going on maternity leave at least once. This is more than one-in-six of both female nurses/midwives aged under 50 and female doctors/dentists aged under 50.

How do contracted hours change after maternity leave?

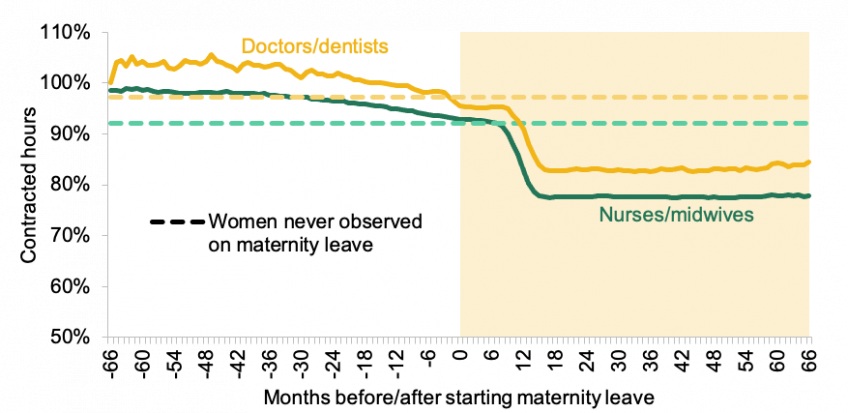

Figure 1 shows average contracted hours as a percentage of full-time equivalent (FTE) before and after maternity. Contracted hours drop to around 78% of FTE for nurses/midwives and 83% of FTE for doctors/dentists a year after going on maternity leave, which is the point when most women return to paid work. In both staff groups, despite differences in typical shift lengths, this is mostly driven by switches to contracts of either 60–65% or 80% of FTE. Only around one-quarter of nurses/midwives and fewer than two-in-five doctors/dentists work full-time two years after going on maternity leave. This is a similar pattern to the rest of the public sector, with the exception that, in the NHS, contracts of less than 50% of full-time hours are rare.

Figure 1. Contracted hours before and after maternity leave for women under 50

Note: Unconditional mean contracted non-bank hours (including zeroes) 12 to 36 months after first receipt of maternity pay, hours censored at 200% of full-time. Size of circles represents the number of observations of women one to three years after maternity leave, and the inclusion of specialties is conditional on at least fifteen such women being observed, with smaller specialties grouped together.

We find that the move to part-time work is long lasting. On average, mothers who return to work part-time do not increase their hours for at least six years after their maternity leave began. Their contracted hours remain flat even after their youngest child reaches school age. We find that the difference between actual and potential hours of female nurses/midwives who had a youngest child starting school in September 2019 (based on maternity leave dates) was the equivalent of 2,400 FTE nurses in early 2020. This figure is just for a single year group, for whom we can observe both maternity leave and school entry. We would expect the number to be several times larger for all nurses who have a youngest child of primary school age. If women are supported, it may be possible to encourage some to work some more hours as their children get older. However, unless women are comfortable to do so, efforts to increase hours could be counterproductive through negative impacts on productivity and retention.

The hours that women work after maternity leave vary by NHS trust

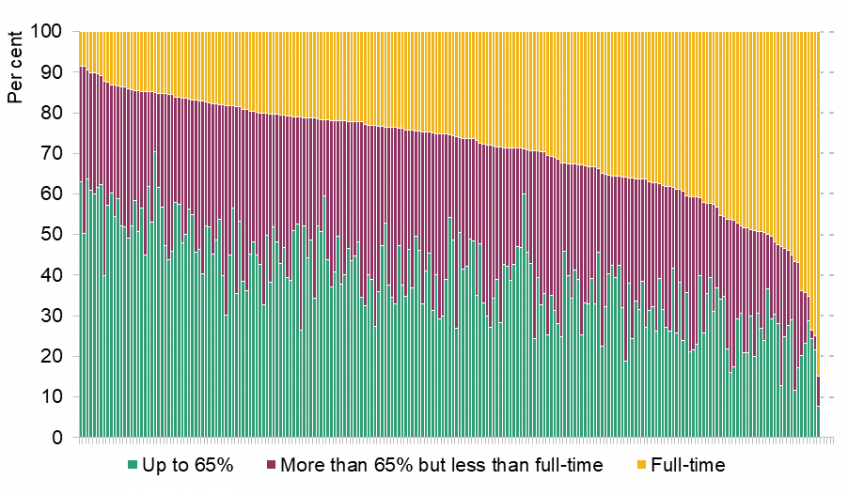

Figure 2 shows the distribution of contracted hours for female nurses/midwives one to three years after going on maternity leave, by trust. Each bar represents an NHS trust (a group of hospitals), which are ordered by the share working full-time after returning from maternity leave (from lowest to highest). In some NHS trusts, more than 70% of returning mothers work full-time hours; in others, fewer than 15% do so. Contracted hours for doctors follow a similar pattern. This suggests that there may be differences in the availability of reduced hours contracts across different trusts.

Figure 2. Contracted hours of nurses and midwives by trust after maternity leave

Note: Average over nurse-month observations one to three years after first observed maternity leave. Restricted to trusts with at least 20 individual nurses/midwives observed one to three years after maternity leave, and to nurses and midwives with strictly positive contracted hours. Merging trusts are treated as one trust throughout the period. Trusts are ordered from those with the smallest to the largest number of full-time nurses and midwives.

Since 13 September 2021, NHS staff members have increased rights to request flexible working arrangements. The variation we document suggests that some trusts may experience a greater demand for increased flexible working from this change, while others may already be offering sufficient flexibility.

Maternity and medical specialty

Women now account for almost half of all doctors, but they are not spread evenly across specialties. Most surgical specialties remain heavily male-dominated. For example, 82% of orthopedic and trauma surgeons, and of cardio-thoracic surgeons are men. By contrast, 83% of doctors who work in community sexual and reproductive health are women, as are two-thirds of those in paediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and public health.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the share of women within a specialty and the average hours that women work after maternity leave. There is a clear negative association: among those women who do go on maternity leave, the hours they work when they return as a share of FTE decreases as the share of women within the specialty increases. Women in trauma and orthopaedic surgery and cardio-thoracic surgery – which are male-dominated – work on average around 100% FTE (i.e. very few are part-time). This compares to an average of 72% of FTE among women in public health and 74% among trainees in general practice, which employ more women than men. We see similar patterns in the rates of maternity or the average number of children that women in each specialty have: women in male-dominated specialties have a lower rate of going on maternity leave than women in female-dominated specialties.

Figure 3. Percentage of women and hours of work one to three years after maternity leave, by specialty

There are many possible causes of this pattern, including – but by no means limited to – differences in training pathways or the availability of part-time contracts across specialties. If we wish to increase the share of women in specialties where they are currently under-represented, the compatibility of work in these specialties with caring responsibilities – and how it could be made more compatible – needs to be a key consideration.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.