The IFS Green Budget 2022 takes stock of the economic and fiscal outlook following Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget and analyses the challenges ahead.

- Business and investment

- Consumption and prices

- Employment and income

- Government finances and spending

- Health and social care

- Poverty, inequality and social mobility

- Taxes and benefits

- Public finance

- Government spending

- Health

- NHS

- Benefits

- Pensioner benefits

- Working age benefits

- State pensions

- Corporate taxes

- Income taxes

- Property taxes

- Tax

- Taxes on wealth and spending

Downloads

IFS Green Budget 2022

PDF | 4.07 MB

The IFS Green Budget 2022, in association with Citi and with funding from the Nuffield Foundation, takes stock of the economic and fiscal outlook following Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget and analyses the challenges ahead.

Below are summaries of each chapter. Click here to read chapters in full:

Chapter 1. Global economic outlook: heading for a fall?

Chapter 2. UK outlook: why we need to do things differently

Chapter 3. Outlook for the public finances

Chapter 4. Public spending, pay and pensions

Chapter 5. Reforms, roll-outs and freezes in the tax and benefit system

Chapter 6. Corporation tax and investment

Chapter 7. Quantitative easing, monetary policy implementation, and the public finances

Launch event and slides

Welcome to the IFS 2022 Green Budget.

It is difficult to overstate the scale of the economic shift since last year’s Green Budget. Inflation has returned with a vengeance and forecasts for real economic growth have become much gloomier. Partly as a result of much higher energy prices, a “terms of trade” shock is squeezing household budgets and living standards.

Much of this year’s Green Budget focuses on the direct and indirect consequences of lower growth and higher inflation. These combined with rising interest rates, and a large discretionary fiscal loosening have put the UK public finances in a substantially weaker position. A huge amount depends on the precise forecast for economic growth, but it is difficult to escape the conclusion that, as it stands, we are not on a sustainable fiscal path. The adverse market reaction to the new Chancellor’s ‘mini-Budget’ shows the importance of fiscal and institutional credibility – hard won but easily lost. There is a lot riding on the Medium-Term Fiscal Plan, due later in the autumn.

Higher inflation is also reshaping the tax and benefit system, owing to the large number of parameters in the system which are frozen in cash terms, whether by default or deliberate policy decision. When inflation is higher, freezes to tax thresholds raise more revenue, more earners are dragged into higher tax bands, and policies like the benefits cap affect more families. One can see the appeal for a tax-hungry Treasury, but there are plenty of less opaque and arbitrary ways to raise revenue.

Inflation also raises the stakes when it comes to the potential gains from structural reform of our corporate tax system. Our current system penalises certain forms of investment, while penalising others – distortions which are only exacerbated during periods of high inflation. A package of reforms to rationalise the system and reduce such distortions could make a genuine contribution to a supply-side, pro-growth policy agenda. Though, as ever, the tax system can only ever be part of the answer.

Public services aren’t spared from the impacts of higher inflation. Departmental budgets were set last year on the assumption of much lower inflation and, crucially, lower pay awards than have since been announced. Keeping to those spending plans – as the new government claims it will – would leave departments having to find around £5 billion of savings this year to fund higher-than-expected pay awards. Those awards will, due to high inflation, still mean a real-terms pay cut for millions of public sector workers, after more than a decade in which pay has, for many public sector jobs, already fallen in real terms.

We are thrilled this year to have a Green Budget chapter authored by Sir Paul Tucker, former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, examining the relationship between Quantitative Easing, monetary policy implementation, and the public finances. This is an enormously important topic, and one that will no doubt become increasingly prominent as the Bank of England increases its policy rate and the government becomes increasingly creative in its search for revenue.

We are delighted to continue our collaboration with Citi, now in its fifth year. We are grateful both for their financial support for the Green Budget and for their chapters on the global economic outlook and the outlook for the UK economy specifically. Both provide vital context for the rest of the Green Budget’s analysis.

We are also very grateful to the Nuffield Foundation for the funding it has provided to support the Green Budget. Our most important aim for the Green Budget is to influence policy and inform the public debate. We feel that this has been especially important this year, given the new Chancellor’s decision to make large permanent tax changes without any accompanying forecasts from the OBR. It is particularly appropriate, then, that it should be supported by the Nuffield Foundation, for which these are also central aims.

The continuing support that the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) provides for our ongoing research work via the Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS (ES/T014334/1) underpins all our analysis in this volume and is gratefully acknowledged. Statistical data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and accessed through the Secure Research Service has been used. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. Data from the Labour Force Survey (1993–2022) are available from the UK Data Service, as is the Living Costs and Food Survey and the Family Resources Survey. This work uses research data sets that may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. The data owners and suppliers bear no responsibility for the interpretation of the data in this book.

As with all IFS publications, the views expressed are those of the named chapter authors and not of the institute – which has no corporate views – or of the funders of the research.

Paul Johnson

Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies

Follow Paul on Twitter @PJTheEconomist

Since 1982, the Green Budget has provided a comprehensive and independent assessment of the state of the public finances ahead of the Chancellor’s Budget and Spending Review. Its meticulous analysis secures the foundations for a more transparent, evidence-based public conversation about how to respond to the economic and social challenges currently facing the UK and it enables the government’s own account to be held up to scrutiny.

Last year’s Green Budget was published in the context of the COVID-19 recovery, Brexit and the transition to net zero. Those issues remain highly relevant but are now overlaid by war in Ukraine and its implications for the UK and world economies. In addition, there is a new government with new economic plans and priorities. The need for a rigorous and impartial analysis of the UK’s situation has never been greater.

We are in a time of rapid inflation, rising interest rates, growing national debt and intense pressure on many government services. The IFS Green Budget sets out the difficult choices and trade-offs involved, in a current context where the least well-off face particular vulnerability. Whilst there is an undoubted necessity to set the UK on a path to a growing economy and sustainable public finances, this is set against a need to support vital public services and respond to the immediate pressures on people and families most under strain from rapidly rising food and energy costs.

In addition to setting out valuable economic context, each year the Green Budget also focuses in on chosen topics. These chapters amount to a hugely comprehensive volume of policy analysis and knowledge built up over time. The focus this year on business taxes and investment, income taxes and benefits, and departmental finances including public sector pay could not be more timely.

In its framing of the economic outlook, the IFS shows that ultimately, the questions to be addressed are about people’s well-being, individually and collectively, in a time of economic uncertainty. These issues are central to the Nuffield Foundation’s work to advance social well-being and to understand the foundations and pathways to a more just and inclusive society. That is why we are now in our tenth year of supporting the Green Budget. Thank you to the IFS and Citi for once again providing such timely and important analysis.

Tim Gardam

Chief Executive

Nuffield Foundation

We are delighted to be collaborating again with the Institute for Fiscal Studies on the production of the Green Budget. IFS continues to shine a critical and objective light on the key issues facing the UK public finances. IFS reports are always essential reading for policymakers, investors and corporate leaders alike. With the UK economy still grappling with the economic impacts of Brexit and the pandemic, the dislocations to geopolitics and global energy markets caused by the war in Ukraine have created unprecedented conditions for the Treasury and public policy in a modern economy. The crisis in the Conservative party and the change of Prime Minister have amplified uncertainties. Our analysis is based on what we believe central bank and government policy trajectories to be, but we recognise that policy could change quite rapidly even if the current UK Parliament is to run to its full term in 2024.

Citi’s economists have provided two chapters for this year’s Green Budget. Our first chapter looks at the global economic outlook. Here we outline a less than rosy outlook for the economy ahead. Post-pandemic supply disruption has proven more persistent than expected, and the addition of the impact of higher energy prices in Europe risks yet further economic pain right on the UK’s doorstep. Geopolitical concerns suggest further global supply shocks are likely to keep coming, with transatlantic relations with China under growing strain. In the near term, high inflation looks set to stay and will trigger further significant interest rate hikes from central banks. Fiscal policy seems at growing risk of simultaneously jumping on the accelerator, just as monetary policy slams on the brake.

Our second chapter reviews the UK economy. Here we outline a challenging outlook for both households and firms, with few ‘easy answers’ from a policy perspective. The full impact of the terms-of-trade shock will, we think, only become clear over the coming months. Alongside the cost shock itself, we also expect higher rates to weigh heavily, pushing any meaningful recovery back into the second half of 2024. This is more than just an issue of low demand. Instead the UK faces a tricky combination of severe supply disruptions, low unemployment and high inflation. With structural economic shocks potentially set to grow more common, we argue this calls for a different policy approach.

I would like to thank Christian Schulz and Benjamin Nabarro from Citi’s European Economics team for their detailed work in compiling respectively the global and UK chapters for this year’s Green Budget. I would also like to thank IFS for the opportunity to collaborate again on the Green Budget.

Andrew Pitt

Global Head of Research

Citi Institutional Clients Group

Citi Research

Citi Research focuses on delivering the highest quality company, sector, economic and geographic insights to our clients globally. The unit includes equity and fixed income research, economic and market analysis and product-specific analysis to help individual and institutional clients navigate a complex global marketplace. Citi Research is committed to maintaining the highest level of independence and objectivity in its proprietary products and insights.

Citi Bank

Citi, the leading global bank, has approximately 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 160 countries and jurisdictions. Citi provides consumers, corporations, governments and institutions with a broad range of financial products and services, including consumer banking and credit, corporate and investment banking, securities brokerage, transaction services, and wealth management.

www.citigroup.com | @Citi

The Nuffield Foundation

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social well-being. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare, and Justice. It also funds student programmes that provide opportunities for young people to develop skills in quantitative and scientific methods. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation.

www.nuffieldfoundation.org | @NuffieldFound

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Christian Schulz

New shocks are threatening to cut the global post-pandemic recovery short. This time last year, successful vaccination programmes, as well as a shift in strategy away from containing to living with the pandemic, had reduced the threat of health restrictions. Economies were expected to re-open, households were expected to deploy savings accumulated during the pandemic and, although it would take some time to restore global supply chains, strong growth was expected for all regions of the world.

Indeed, this picture broadly played out in the second half of 2021. Economies gradually reopened and the gaps between post-pandemic recoveries narrowed. By Summer 2022, Europe’s GDP recovery had nearly caught up with that of the US. However, especially in the US, the recovery may have been too fast for its own good.

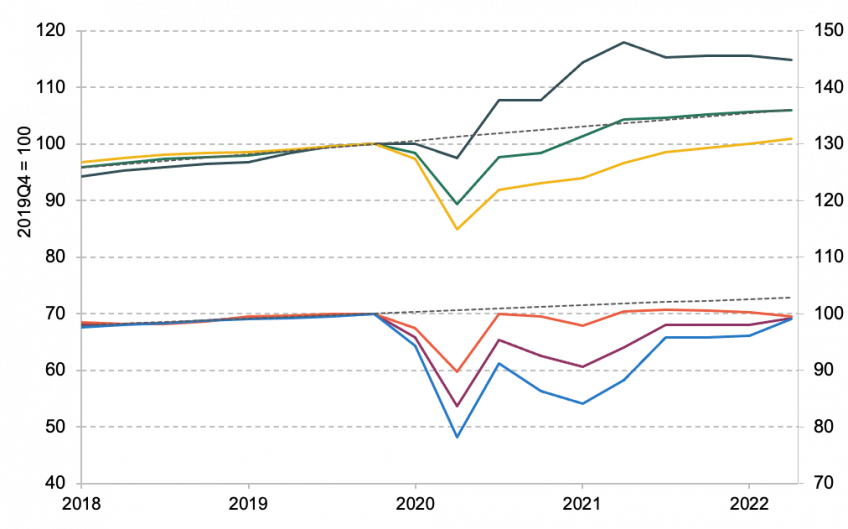

US and Eurozone: real private consumption

Source: BEA, Eurostat and Citi Research.

Turbocharged by the extremely generous post-election fiscal stimulus, the American economy began overheating to which, with hindsight, the Fed may have reacted too late. As a result of (belated) hikes in short-term policy rates, plus sharp increases in longer-term government and corporate borrowing costs, the US dollar strengthened against most other currencies and exported the US inflation problem to the rest of the world.

In these already challenging circumstances, a new and major speed bump appeared in the form of the conflict in Ukraine. Energy prices in general, and natural gas prices in Europe in particular, surged to extreme levels. This ‘tax’ on the economy is starting to take its toll on household real income and confidence. Europe looks set for a potentially deep recession. This will eventually probably reduce (and potentially eliminate) Europe’s inflation problem, leaving less for monetary policy to do. In the US, however, monetary tightening will likely have to go a lot further to restore the balance between supply and demand in the labour market and bring inflation under control. While potentially strengthening the dollar further, that will probably also imply a recession, albeit a milder and later one than in Europe.

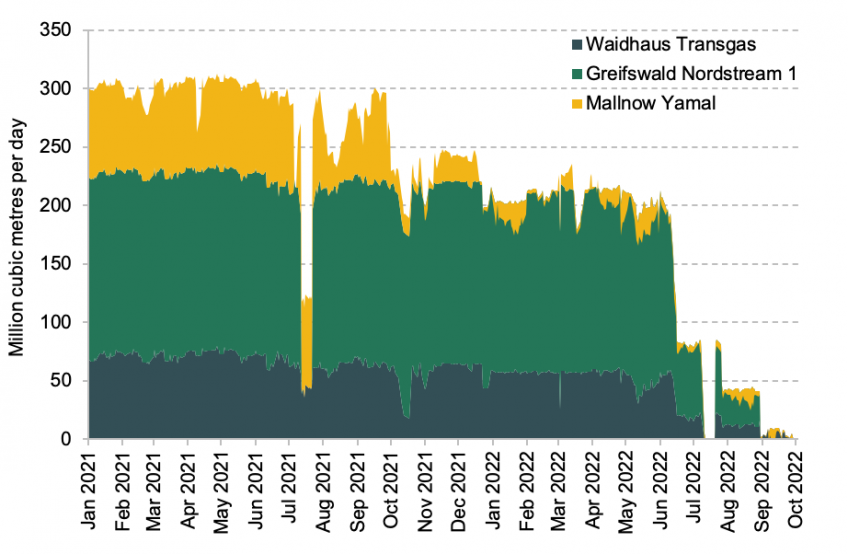

Germany: pipeline gas inflow from Russia

Source: Bloomberg and Citi Research.

Key findings

1. This year’s global economic outlook is far less rosy than in 2021. We expect the global economy to grow by 2.9% this year and 2.5% next year, both well below the long-run average of 3%. Europe, in the short term, and the US, later in 2023, are likely heading for recession.

2. Post-pandemic supply–demand imbalances have proved more severe and persistent than expected. Indicators of supply chain disruption such as shipping prices have declined, but not normalised. Expansive government policies have driven up public debt ratios by up to 20% of GDP and boosted money supply by 20–40%. Even leaving aside volatile food and energy prices, where, in our view, idiosyncratic shifts in supply and demand dominate, the ranking of the rises in core prices in the US, the UK and the Eurozone between 2019Q4 and 2022Q2 by 4%, 3% and 2% annualised, respectively, mirrors the ranking of the fiscal and monetary expansions.

3. The war in Ukraine and the stand-off with Russia have aggravated the inflation crisis by eliminating 40% of the EU’s gas supply, triggering a severe energy crisis in most of Europe. The increase in gas prices alone is imposing a burden of up to 8% of GDP on European households and firms. European gas prices peaked at double Asian rates and 10 times the US’s. This price shock is likely to trigger a recession, but also lead to structural changes in the European economy, weighing on growth for many years.

4. The Ukraine conflict also raises questions about the West’s reliance on China. Reducing dependence on the 22% of EU goods imports coming from China, including even higher shares for technology and consumer goods imports, may be an even greater challenge than reducing dependence on Russian energy. And unlike Russia, China remains tempting as an export market, absorbing 10% of EU exports and growing at triple the rate of overall exports. Improved resilience of supply chains may come at the cost of a permanent reduction in expected economic potential.

5. The series of supply shocks has driven global inflation to 7% this year. Recession, as well as base effects in energy and the gradual unwinding of supply chain disruptions, will likely bring inflation below 6% in 2023 and to 3.5% in 2024. But even that is still above the 3% long-run average. Inflation in energy and goods prices is being replaced by inflation in the price of food and services. High inflation looks set to stay and should trigger further significant interest rate hikes from central banks.

6. Governments can arguably be more effective in fighting inflation than central banks. They can invest and deregulate to boost energy supply and unclog supply chains, but also reduce demand by fostering industrial adaptation. Many are acting to preserve supply by guaranteeing loans or nationalising critical energy infrastructure, but also by supporting demand with tax cuts and subsidies. In the EU, fiscal measures related to the crisis amount to 3–4% of GDP already and are expanding rapidly. While direct interventions in energy prices have lowered measured inflation rates by 3 percentage points, some measures cause inflation elsewhere or in the future.

7. However, fiscal policy has to tread a fine line, as it can also distort incentives to save energy and raise the risk of blackouts as well as lower long-term incentives for the economy to adjust to potentially permanently higher energy prices and less efficient supply chains. So far, finance ministers are enjoying a tax revenue bonanza due to high inflation, but as they expand their support, risks to debt sustainability will grow and limit fiscal space, forcing hard choices.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Benjamin Nabarro

The UK is the talk of the town, and not in a good way. The coordinated sell off in both gilts and sterling reflect growing concerns about both the health of the economic recovery and the viability of the UK’s policy approach. With monetary and fiscal policy still at loggerheads, the risk of further financial disruption remains acute in the months ahead.

The UK begins in a relatively weak position. The UK is the only G7 economy not to have re-attained its pre-Covid level by the second quarter of 2022. And worse likely remains ahead, with our forecast suggesting that GDP will fall by 0.7% through 2023. The predominant driver of the economic outlook here is the large terms of trade shock. Recent increases in energy prices compound established increases in both food and core goods prices. In each case, this implies price pressures today and crimped incomes tomorrow. We expect that to mean a limited consumer driven recession over the coming quarters, despite additional support.

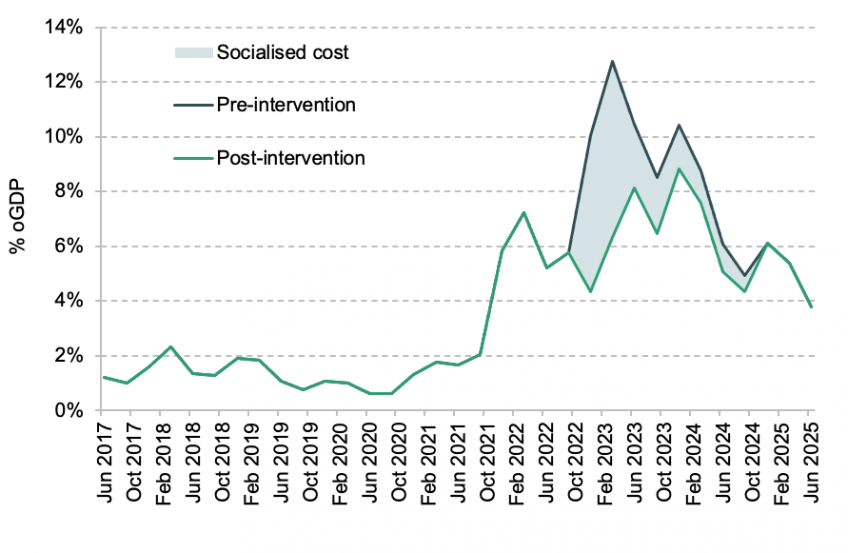

UK – Spending on Gas and Electricity (% GDP), 2017-2025

Notes: Figures are presented here as a share of quarterly nominal GDP. Spending is conditioned on a Citi VAR model of consumption substitution across sectors, alongside current market futures prices.

Source: ONS, Department for Business and Industrial Strategy, Bloomberg LLP and Citi Research.

For now, a weak demand side sits alongside a supply picture that is also heavily impaired. Here, a reduction in labour supply alongside ubiquitous matching challenges mean the UK labour market remains relatively tight. For the Monetary Policy Committee, the concurrence of a tight labour market and very strong imported inflation mean some action is necessary to reduce the risk of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. But this will come at a longer-term cost. While a limited supply recovery seems likely, without carefully targeted support, the risk of material long-term economic scarring is growing.

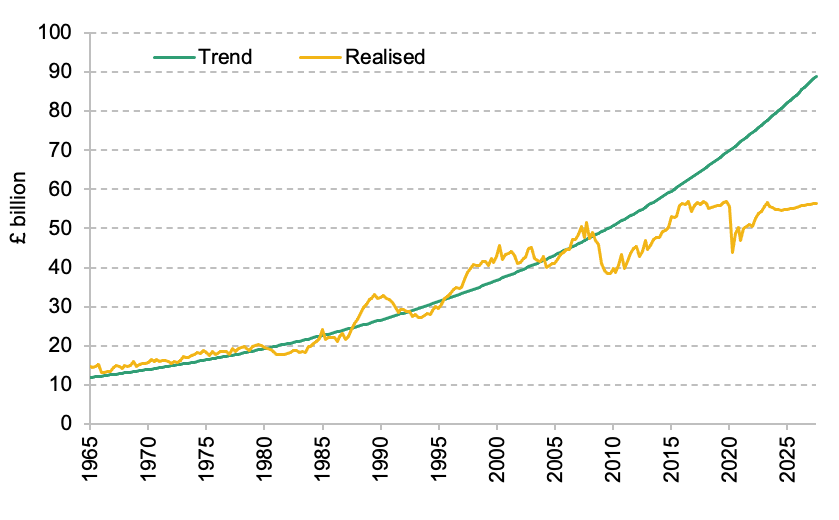

UK – Business Investment (£ 2019 bn), 1965-2027

Notes: Trend business investment growth is based growth between 1965 and 2007.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Overall, policy faces a tricky trade-off between risks of a self-propagating recession on the one hand, and a nominal de-anchoring on the other. Sweeping fiscal stimulus is likely only to mean an outsized monetary response and a weaker long-term recovery. At the same time doing nothing is also far from optimal. The core conclusion we draw from recent experience is that policy would fare better by focusing more directly on managing the supply side of the economy. With structural shocks likely to grow more frequent in the decade ahead, that suggests a structural shift in approach.

Key findings

1. The UK can ill afford any more economic policy mistakes. After a lost decade, the government is right to focus on increasing growth. However, it must do so amidst two tightening constraints. The first is institutional credibility. The second is the need to develop appropriate tools to manage increasingly frequent adverse ‘supply-side’ shocks.

2. In the near term, the key challenge facing the UK economy is the terms-of-trade shock – an increase in the price of imports relative to exports. These effects are boosting inflation, but crimping domestic income. We expect these effects to weigh heavily on demand across both the household and corporate sectors over the coming year. The main upside economic risk remains a sweeping reduction in gas prices. Absent this, however, the UK economy is likely to be structurally poorer. The key policy question is how this loss is allocated.

3. For households, the looming cost shock will hit hardest those least able to bear it. Consumption is likely to be weighed down heavily by looming cost increases. The regressive nature of the shock risks exacerbating the near-term economic impact, particularly as consumer credit conditions continue to tighten. We think this should also argue against policies that transfer away from poorer households to their wealthier equivalents. ‘COVID savings’ also seem unlikely to come to the rescue given the mismatch between their accumulation and those suffering the largest real income shocks. In the medium term, sharp increases in mortgage costs may push any consumer recovery into 2024.

4. The weakness on the supply side of the UK economy is now an urgent concern. While output is 2.6% short of its pre-COVID trend, we estimate current excess demand in the order of 1.4% of GDP. Supply should gradually recover in the months ahead as capital and labour gradually reallocate. Targeted support has a key role to play in aiding reconfiguration and boosting incomes, but sweeping fiscal giveaways risk making a bad situation worse. The risk of a greater long-term scarring seems to be increasing.

5. We expect unemployment to increase from here as demand slows, but only gradually. Labour supply should continue to recover as cost-of-living concerns bite and NHS waiting times potentially begin to fall. However, in the near term, labour hoarding effects suggest redundancies are likely to materialise only slowly. Firm insolvencies may prove a key driver of slack in the near term. And in the medium term, unlike with the Great Financial Crisis, we think more persistent labour hoarding effects are likely to prove only limited.

6. Cost pressures remain intense. We expect CPI inflation to peak at 11.8% in the months ahead. While price growth should fall back during 2023, inflation is likely to stay relatively high for a while. And in the interim, the risks of a more nefarious feedback effect into domestic inflation dynamics will remain elevated. For now, we see the risks here as substantial, but contained. However, the sheer level of inflation means uncertainty is particularly high. More monetary tightening is almost certainly needed. De-anchored and expansionary fiscal policy remains the key upside risk to medium-term inflation.

7. The adverse market reaction to the ‘mini-Budget’ was qualitatively different from that to previous events. We think that reflects the now acute conflict between monetary and fiscal policy. In the near term, that calls the UK’s broader institutional credibility into question. In the medium term, it likely means weaker macroeconomic outcomes as the Monetary Policy Committee is forced to ‘overcompensate’ for continued fiscal stimulus. Historically, these shocks have tended to weigh on long-term output as tighter financial conditions weigh on investment.

8. Recent experience shows you cannot effectively manage supply-driven inflation via demand. Policy faces a tricky trade-off steering between the risk of a self-propagating recession on the one hand and the risk of de-anchoring inflation on the other. In our view, a different policy approach is not just desirable, but necessary. The fundamental challenge here stems from the supply-driven nature of the economic shock. Such shocks are likely to occur more frequently than in the past. The current approach risks hampering medium-term growth.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Carl Emmerson and Isabel Stockton

Just seven months after the last set of official forecasts for the economy and the public finances was presented at the Spring Statement in March, much has changed. Soaring inflation has pushed up debt interest spending and depressed growth prospects. Substantial permanent tax cuts leave borrowing elevated and debt on a rising path as a share of national income, even after short-term expensive energy support for households and businesses is expected to expire.

A clear lesson from the Global Financial Crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and the current cost of living crisis is that there are emergency periods where government needs to provide temporary support and that it is appropriate for debt to rise during those times. Trying to prevent debt from rising during a sharp economic downturn would be wrong and, most likely, futile. But it is certainly unsustainable for policies to leave debt on a path where it relentlessly grows as a share of national income. And wanting the ability to raise debt when the next sizeable adverse shock hits provides a reason to aim to have debt falling outside of crises.

Uncertainty around any public finance forecast means that it is always possible that debt will fall as a share of national income. But unless – through luck or a concerted and successful policy effort – the economy grows at a substantially higher rate than under our current forecast, even just stabilising debt would require difficult decisions on some combination of spending cuts and tax rises.

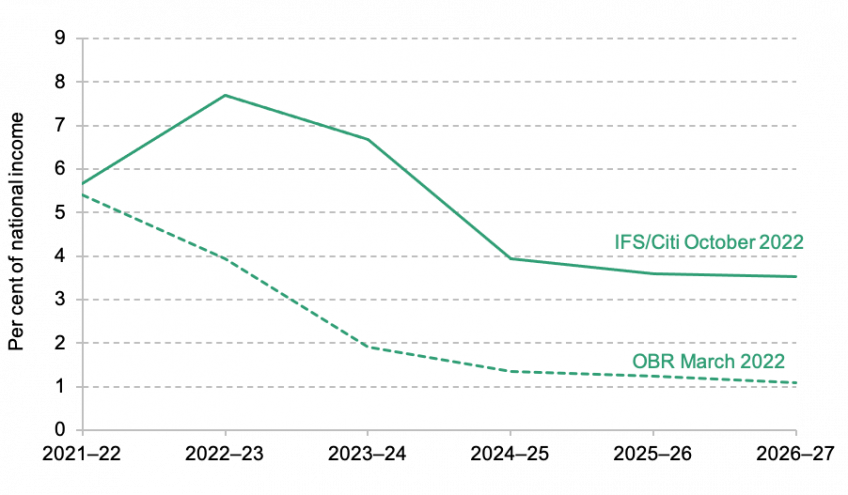

Forecast borrowing, per cent of national income

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March 2022; authors’ calculations.

Key findings

1. The most recent official economic and fiscal forecasts, from March 2022, had the government meeting its fiscal targets with a current budget surplus (i.e. total revenues exceeding day-to-day spending) from 2023–24 onwards and underlying public sector net debt on course to fall, albeit modestly, as a fraction of national income from the same year. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) calculated that the government’s mandate to have debt forecast to fall was met by a margin of £28 billion.

2. Much has changed. Under Citi’s macroeconomic forecast, which underpins our analysis of the public finances, rising inflation and interest rates will add to public spending on working-age benefits, state pensions and debt interest. Recent policy decisions, such as the Energy Price Guarantee and the new government’s package of permanent tax cuts, will also add to borrowing. Overall, we forecast that borrowing this year will be £194 billion, which would be £94 billion higher than the £99 billion forecast in March. Of this increase, £68 billion is explained by support for energy bills announced since March (net of revenues from the new energy profits levy).

3. But more important for the sustainability of the public finances is the outlook for borrowing in the medium term. Even once the energy support packages are assumed to expire, borrowing remains elevated. There is huge uncertainty around the exact magnitude, but under a central forecast in 2026–27 we expect borrowing of £103 billion, which would be £71 billion higher than forecast in March. Much of this increase is uncertain – it will in particular depend on the path of the economy, inflation and interest rates – but less uncertain is £43 billion of the increase in borrowing, which is explained by the direct impact of the permanent tax cuts announced by the new Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng.

4. We forecast that spending on debt interest will be £103 billion in 2023–24, double the £51 billion forecast by the OBR in March and which was already an upwards revision on the £39 billion the OBR forecast in October 2021. Much of this increase in debt interest spending will dissipate as long as inflation falls back. But even in 2026–27 we forecast that debt interest spending will be £66 billion, some £18 billion higher than forecast by the OBR in March, £26 billion more than forecast in October 2021 and £9 billion more than was spent in 2021–22, as a result of higher interest rates and a higher level of accumulated debt.

5. In line with stated government policy, we assume that the government keeps broadly to the departmental spending plans set out a year ago. This is despite rising inflation eating into the implied real increases: restoring their generosity would require an additional £14 billion of spending in 2023–24 and £23 billion in 2024–25. Keeping to the existing cash spending plans is essentially imposing a rather hidden form of austerity on departments, and doing so in a rather arbitrary way, as it depends on the extent to which rising prices are adding to the spending pressures of each department – which will not be equivalent across the public sector.

6. The Chancellor has promised a ‘fully costed plan to get debt falling in the medium-term’. Pushing back the definition of the medium term from three years to five years could make this aim easier, but still far from easy, to meet. Under Citi’s central forecast, it would require a fiscal tightening of £62 billion in 2026–27 to stabilise debt as a fraction of national income – so even reversing all of the permanent tax cuts in Mr Kwarteng’s ‘mini-Budget’ would not be enough. Higher growth would help – but even if growth turned out to be 0.25 percentage points a year stronger than Citi expects, a fiscal tightening of £41 billion would be required to stabilise debt.

7. The government might be inclined to deliver any fiscal tightening through spending cuts. Supposing £62 billion of cuts were required, one way to achieve this would be as follows. Indexing working-age benefits to growth in earnings rather than prices in the next two years would cut spending by £13 billion, with most of the losses being felt by working-age households in the bottom half of the income distribution. A further £14 billion could come from cutting investment spending plans to 2% of national income, though this might be difficult to square with a government intent on boosting growth. The remaining £35 billion could come from a 15% cut to day-to-day spending on public services outside of the NHS and Ministry of Defence budgets, but this would require cutting spending in many areas where deep cuts were delivered between 2010 and 2019. Such spending cuts could be done, but would be far from easy.

8. Uncertainty around any public finance forecast means it is possible debt will fall as a share of national income. But being able to realistically expect it to fall requires a central view of economic growth and what tax and spending policies will actually be pursued. While we should hope for better growth, the rationale for an independent OBR is to ensure that politically motivated wishful thinking is not incorporated into economic and fiscal forecasts. The OBR should continue its practice of not incorporating hoped-for growth improvements arising from supply-side reforms until evidence of stronger growth starts to emerge.

9. Recent events have illustrated the importance of a credible strategy and plan for fiscal sustainability. Just as financial markets – which ultimately have to lend the money required to plug the gap in the government’s fiscal plans – might be unconvinced by plans underpinned by an assumption of a miraculous uptick in growth, so too might they be unconvinced by plans underpinned by vague promises of public spending cuts far into the future. We need to avoid the situation Mr Kwarteng wrote about in 2012 where ‘in each new budget the government promised their books would balance tomorrow – but tomorrow never seemed to arrive’. The OBR should therefore be very wary of a promise to cut spending in four or five years’ time without sufficient detail of where the axe would fall.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Bee Boileau, Laurence O’Brien and Ben Zaranko

The Chancellor faces a difficult range of trade-offs this autumn. Public sector pay awards must be higher than was assumed last October, when departmental funding was fixed in cash terms over the next three years. Affording these higher pay awards will require departments to make painful cuts to headcount or other budgets if settlements are not topped up. We estimate that pay awards of 5% on average – as were awarded public sector workers this July – impose additional costs of £5billion on departments, which could require workforce cuts of more than 100,000. These problems will only be amplified over the next two years.

5% pay awards are below inflation of around 10%, meaning public sector workers receive a 5% real-terms cut; they are also likely to fall behind pay growth in the private sector. Over the last decade, public sector pay has been falling relative to the private sector, and the public-private pay differential is now lower than it has been at any point in the last 30 years.

This chapter analyses the implications for public spending and employment of a range of potential public sector pay awards, both in this year and over the next two. We then move on to look at remuneration in the public sector in comparison to the private sector – how the differential has changed, accounting for workers’ characteristics, for a range of different groups over time. We estimate both the headline pay differential and the total remuneration differential, which takes employer pension contributions into account. Finally, we consider some longer-term policy implications, in particular the optimal balance between take-home and deferred pay in the public sector.

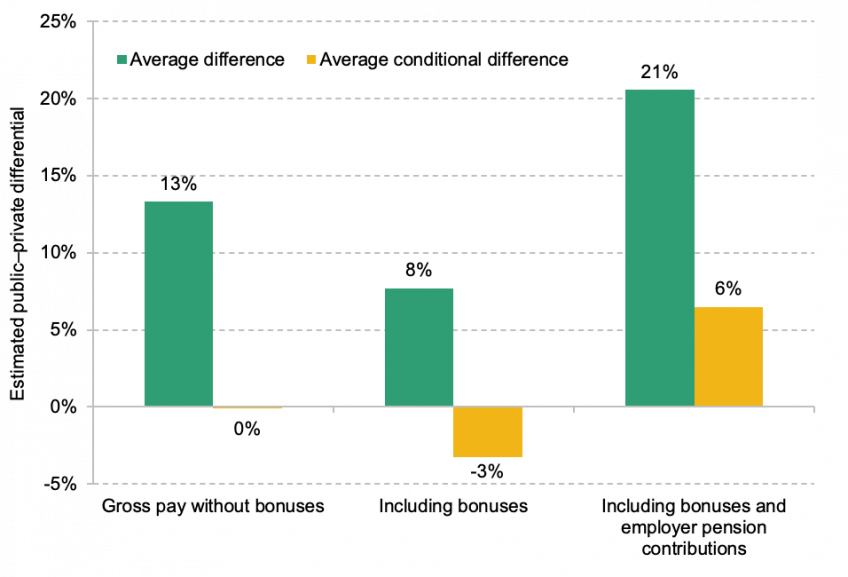

Average public–private hourly pay and remuneration differentials in 2021

Notes and sources: see Figure 4.14 of Boileau, O’Brien, and Zaranko (2022).

Key findings

1. The public sector pay settlements announced this July will pose severe budgetary challenges for many areas of government. Overall funding for public services was fixed in cash terms for the next three years in last October’s spending review, at which this year’s double-digit inflation was not predicted. Departmental budgets were predicated on pay awards in the region of 3%, far below the current rate of inflation, and below the pay awards of roughly 5% (on average) announced over the summer. These pay awards are estimated to increase departmental staffing costs by around £5 billion this year, compared with the (approximate) 3% baseline built into existing spending plans. Offering an inflation-matching pay award to all public sector employees would add more like £18 billion.

2. Departmental funding settlements have not been increased to account for these additional costs. Meeting them from within existing budgets will be especially challenging given the context of sharply rising energy prices and elevated general inflation, which reduces the scope for savings elsewhere. If costs were met entirely through cuts to employment (i.e. to keep the total wage bill to what was expected when the spending settlements were made), a reduction of approximately 110,000 public sector workers (or 1.9% of the projected 2022–23 public sector workforce) would be necessary this year. Full inflation protection for public sector employees would increase that number to 390,000 (or 6.8% of the workforce). If some areas of government (e.g. the NHS) were exempt from any headcount cuts, the required cuts elsewhere would be deeper.

3. The challenge is, if anything, more acute in future years. Compensating departments for the additional costs of the pay awards this summer would mean an additional £5 billion or so this year (2022−23); if pay awards matched inflation after this year, that figure would rise to more than £10 billion by 2024−25. If no such compensation were forthcoming, the government would have to cut headcount by more than 220,000 by 2024−25 (or 3.8% of the projected 2024–25 public sector workforce) to stay within existing plans for the staff pay bill. If, instead, the government offered inflation-matching pay awards this year and each of the next two years, the additional costs would rise to around £25 billion by 2024−25, or the headcount reduction required to stay within existing budgets to 500,000 (8.6% of the public sector workforce).

4. The new Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng must either top up those spending plans to fund these higher-than-expected pay awards or accept that the quality of public services will (further) deteriorate. This is one of the central fiscal choices for this autumn. Indeed, this could be among the defining decisions of the remainder of this parliament.

5. There is a case for reforming the fiscal framework to lessen the disconnect between the planning horizons for public sector pay (set annually) and departmental budgets (set on a multi-year basis). That could be achieved by setting the same planning horizons for both; longer-term horizons, though, would exacerbate pre-existing problems of public sector pay inflexibility, and shorter-term horizons might impede departments’ ability to budget effectively. Our preference would be to instead reform the spending framework, so that settlements are automatically reopened and reassessed in exceptional circumstances, defined as occurring when pay and/or other cost increases deviate sufficiently from the assumptions made (and published) when plans were originally set.

6. Even the higher-than-budgeted pay awards this year may not be enough to head off concerns around recruitment and retention – or widespread industrial action. The vast majority of public sector workers will experience a real-terms pay cut this year, and are likely to experience a bigger real-terms cut than their counterparts in the private sector. Public sector pay awards of 4–5% this year imply real-terms cuts of more than 5%, and are broadly similar to expected private sector pay settlements of around 6% (though may compare less favourably when bonuses, more widespread in the private sector, are taken into account).

7. The gap between pay growth in the two sectors this year is unlikely to be especially large, but comes after a decade in which public sector pay has been falling relative to the private sector and, for many public sector jobs, falling in real terms. The government needs to ensure it has the right number and mix of staff to provide its desired range and quality of public services. It is therefore essential to consider trends in public and private sector pay (and overall remuneration) together: the private sector helps define outside options for public sector workers. The continuing fall in public sector pay relative to the private sector poses recruitment and retention challenges for public services, and could threaten the government’s ability to deliver on its public service objectives (such as clearing the NHS backlog, ‘levelling up’ primary education and reforming adult social care funding).

8. The raw difference between public and private sector hourly pay levels, which does not take account of the different characteristics of employees in the two sectors, has fallen from 13% in 2007−08 to 7% in 2021−22. The conditional public–private pay differential, which controls for the fact that public sector workers tend to be more educated, older and more experienced, has fallen steadily from around 3% in 2007−08 to slightly below zero in 2021−22. This public–private pay differential is now less favourable to the public sector than at any point in the past 30 years. This is true of both men and women, though the estimated public–private pay differential for women in 2021−22 remains positive (+2.2%) and considerably higher than for men (−4.6%).

9. Alongside pay, employer contributions to pension schemes are an important part of the overall difference between public and private sector remuneration. Public sector workers are much more likely to be enrolled in a workplace pension (91% had a workplace pension in April 2021, compared with 75% of private sector employees) and more likely to be in – typically much more generous – defined benefit schemes (82% were in a defined benefit scheme in 2021, compared with 7% of private sector workers). Whereas almost half (47%) of public sector employees received an employer pension contribution of at least 20% of their pay in 2021, the same was true of just 2% of private sector employees.

10. The relative generosity of employer pension contributions in the public sector has been growing over time. The average employer contribution rate in the public sector grew by around 5 percentage points between 2012 and 2021, rising to 18% of pay in 2021. The average employer contribution rate in the private sector is considerably lower and has been growing more slowly: the average across all private sector employees (including those who do not participate in a pension scheme) rose by around 2 percentage points over the same period, reaching almost 6% of pay in 2021.

11. When taking an estimate of employer pension contributions into account, there was a raw difference of 21% between average public and private sector remuneration in 2021. When controlling for employee characteristics, we estimate the average public–private remuneration differential to be around 6% (meaning that public sector workers are paid roughly 6% more than their private sector counterparts on average, once pensions are accounted for). This total remuneration differential has fallen in recent years, but to a lesser extent than when considering pay alone, as a result of the increasing relative generosity of public sector pension contributions.

12. There is a strong case for rebalancing public sector remuneration away from pensions and towards pay. A far greater share of overall public sector remuneration is deferred, in the form of both employer and employee pension contributions, compared with the private sector (20.1% versus 7.6% on average in 2021), and this difference has been increasing over time. That means for a given level of remuneration, take-home pay is lower in the public sector. One option, as a starting point, would be to reduce employee pension contributions in the public sector, alongside a commensurate decrease in pension generosity. That would increase take-home pay for public sector employees with no change to the costs for their employers.

13. The public sector pay differential varies considerably across the UK, implying that regions may face varying levels of difficulty with recruitment and retention, and potentially creating unintended and undesirable variation in the quality of public services. The conditional public–private pay (and total remuneration) differential is lowest in London and the South East, and highest in Wales, Scotland and the North East. The average nurse in the North East earns 17% more than the average employee in the region, versus just 5% more in the East of England and 9% less in London. The average secondary school teacher in the North East or Wales earns over 50% more than the average in their region; a secondary school teacher in the South East earns 22% more than the average. Pay is not, of course, the only factor affecting the public sector’s ability to recruit and retain skilled workers, and it is not obvious that the areas with the lowest public–private differential are those facing the greatest difficulties with recruitment.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Tom Waters and Thomas Wernham

Much has been made about the mini Budget’s surviving high-profile tax cuts: the reductions in National Insurance contributions (NICs) and the 1p cut to the basic rate of income tax. Even without the additional rate abolition, these are very big tax cuts relative to plans, and are likely to be enough to put considerable strain on the public finances. But they come in the midst of a four-year freeze to income tax thresholds. Many other tax and benefit thresholds and values are also frozen indefinitely. This matters all the more in the high-inflation environment – and the more uncertain inflation environment – we now find ourselves in. In addition, other reforms (especially benefit changes) are often slowly rolled out, meaning that their impact grows over time.

This chapter shows how the size and shape of the tax and benefit system is set to change over the coming years, taking account of the various freezes, reforms, and discretionary changes. Freezes to thresholds, allowances and benefit amounts are increasing the number of taxpayers, and dragging more people into higher rates of tax, whilst also reducing families’ benefit entitlements.

Given current inflation forecasts, these freezes are set to more than offset headline tax cuts to National Insurance and the basic rate of income tax. By 2025, for every £1 households gain per year from these headline cuts, they lose £2 as a result of freezes. And freezes will dominate these tax cuts across the income distribution, not just on average.

Of course, from the Treasury’s perspective, one can see that undoing such freezes might not be appealing, given the state of the public finances. But that doesn’t change the fact that there are far less opaque and arbitrary ways to raise revenue. Worryingly, it seems like there is a growing trend towards introducing new parameters to the system that are indefinitely frozen. This smacks of lazy policymaking, and the government should kick the habit.

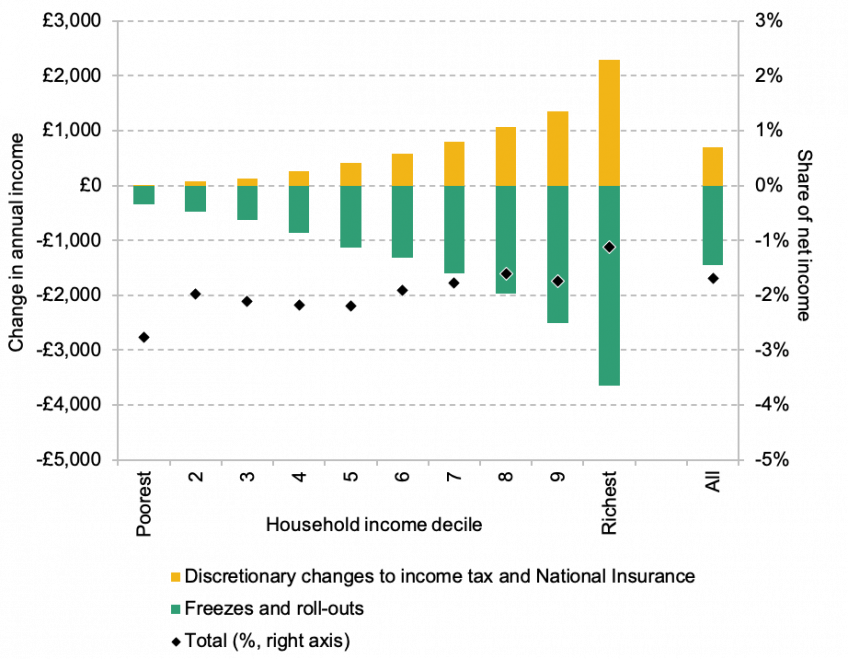

Changes in income by decile: freezes, roll-outs and planned discretionary tax changes to 2025–26

Source: Authors’ calculations using the FRS 2019–20 and TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

Key findings

1. Many tax and benefit thresholds, allowances and amounts (‘parameters’) are by default uprated every year in line with prices or in some cases earnings. But others are frozen in cash terms, sometimes temporarily by explicit policy choices but often indefinitely. Compared with uprating, such freezes reduce household incomes and strengthen the public finances – all the more so in the high-inflation environment we currently find ourselves in. These freezes – which represent a stealthy and arbitrary way to raise tax revenue – often have a bigger impact on household incomes than more eye-catching discretionary measures. Several benefit reforms are also being rolled out over the coming years, which also overall act to reduce household incomes.

2. The range of frozen parameters is wide, covering many aspects of the tax and benefit system. For example, we are one year into a four-year freeze in the income tax personal allowance and higher-rate threshold, which is set to raise the government £30 billion per year when finished. But other parameters are frozen indefinitely – including the £100,000 threshold where the personal allowance begins to be withdrawn, the benefit cap, the maximum assets that universal credit claimants can have, and local housing allowance rates which cap recipients’ housing benefit.

3. Freezes to personal tax parameters alone will reduce households’ income by £1,250 on average by 2025–26. Adding in freezes to benefits and gradual policy roll-outs brings that figure to £1,450, or 3.3% of income, and means a £41 billion boost to the exchequer. That is double the £20 billion gain in household income (and loss to the exchequer) from the high-profile personal tax giveaways – the reduction in National Insurance contributions and 1p cut to the basic rate of income tax. In other words, on average for every £1 households gain from high-profile cuts to rates of income tax and National Insurance, they lose £2 from the freezes and policy roll-outs. Not only does this hold in total, but in every income decile the average impact of gradual roll-outs and freezes outweighs the impact of the explicit discretionary policy changes.

4. The combined impact of headline tax changes, policy roll-outs and frozen taxes and benefits by 2025–26 is broadly regressive, with the poorest seeing income falls of 2.8% of income and the richest falls of only 1.1%. Headline cuts to income tax and National Insurance will benefit higher-income households who are more likely to get more of their income from employment, while the poorest tenth of households will gain only £13 per year from these measures. Because some tax thresholds and – especially – benefits values are indefinitely frozen, the impact of freezes only grows over time. As a result, by 2030–31 the total changes to the tax and benefit system are more clearly regressive, with the highest-income tenth seeing a 1.3% fall in income and the lowest-income tenth a 4.7% fall.

5. Freezes to tax thresholds and benefit values combined with higher-than-expected inflation change the shape of the tax and benefit system. The four-year freeze to the personal allowance and higher-rate threshold (scheduled to run to March 2026) is expected to increase the share of adults paying income tax to 66% (35 million) and the share paying the higher rate to 14% (7.7 million), compared with 63% (34 million) and 11% (6.1 million) today. The point at which the personal allowance begins to be tapered away (£100,000) and the additional-rate threshold (£150,000) have both been frozen since their introduction in 2010. By 2025–26, 3% of adults (1.6 million) will have some of their personal allowance withdrawn, and 1.4% (760,000) will pay additional-rate tax – in both cases around triple the equivalent number in 2010 when the thresholds were created.

6. The freezing of the £50,000 threshold at which child benefit begins to be withdrawn has led to 26% of families with children (2 million) now losing some or all of their child benefit – double the proportion when the policy was introduced a decade ago. In addition, the frozen benefit cap means the number of families with capped benefits could hit around quarter of a million in 2025–26 – double the current figure, and three-and-a-half times as many as when the cap was last actively reformed in 2016.

7. Freezes mean the shape and size of the tax and benefit system change in an uncertain and arbitrary manner, depending on unpredictable changes in inflation. Millions more are set to be paying higher tax rates by 2025–26 than the government could have predicted when income tax thresholds were frozen in April 2021, purely because prices have increased at an unexpectedly high rate. These problems are worse in a high-inflation environment, but even in times of lower inflation, freezes reduce the transparency of tax and benefit reforms, allowing the size of the system to be changed by stealth. All tax and benefit parameters should be uprated by a sensible index. If the government wants to raise taxes or cut benefits, it should tell us what real value it thinks the parameter in question should be, and not let it be unpredictably buffeted around by inflation.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Authors: Stuart Adam, Isaac Delestre and Vedanth Nair

UK business investment is the lowest in the G7 and among the lowest in the developed world.

Tax has a role to play in shaping investment incentives, and the UK’s corporate tax system is one of extremes. While the rate of corporation tax (19%) is exceptionally low, UK investment allowances are amongst the developed world’s least generous. As a result, effective tax rates in the UK (a measure which accounts for the generosity of allowances as well as the headline rate) are middling by international standards. But they vary hugely across different kinds of investment, favouring investment in some assets over others and encouraging borrowing to finance investment.

In this chapter we look closely at the nature of these distortions. We consider how the large package of corporate tax reductions announced in the recent ‘mini-Budget’ is likely to shape incentives to invest and what balance it strikes between encouraging domestic investment and attracting profitable ventures from overseas.

Finally, we consider the road ahead. We examine the likely impact of rising inflation and interest rates. We emphasise the importance of stability and of setting out a clear long-term plan. And we set out a case for genuine structural reform of corporation tax, which could address distortions to the allocation and financing of investment as well as its level.

This chapter was finalised in the wake of the ‘mini-Budget’ delivered to the House of Commons by Kwasi Kwarteng on 23 September 2022. Since then, the main corporation tax announcement in the mini-Budget has been reversed and both Chancellor Kwarteng and Prime Minister Truss have resigned. These developments came too late to be integrated into the chapter before publication. A brief postscript (Section 6.8) acknowledges their implications.

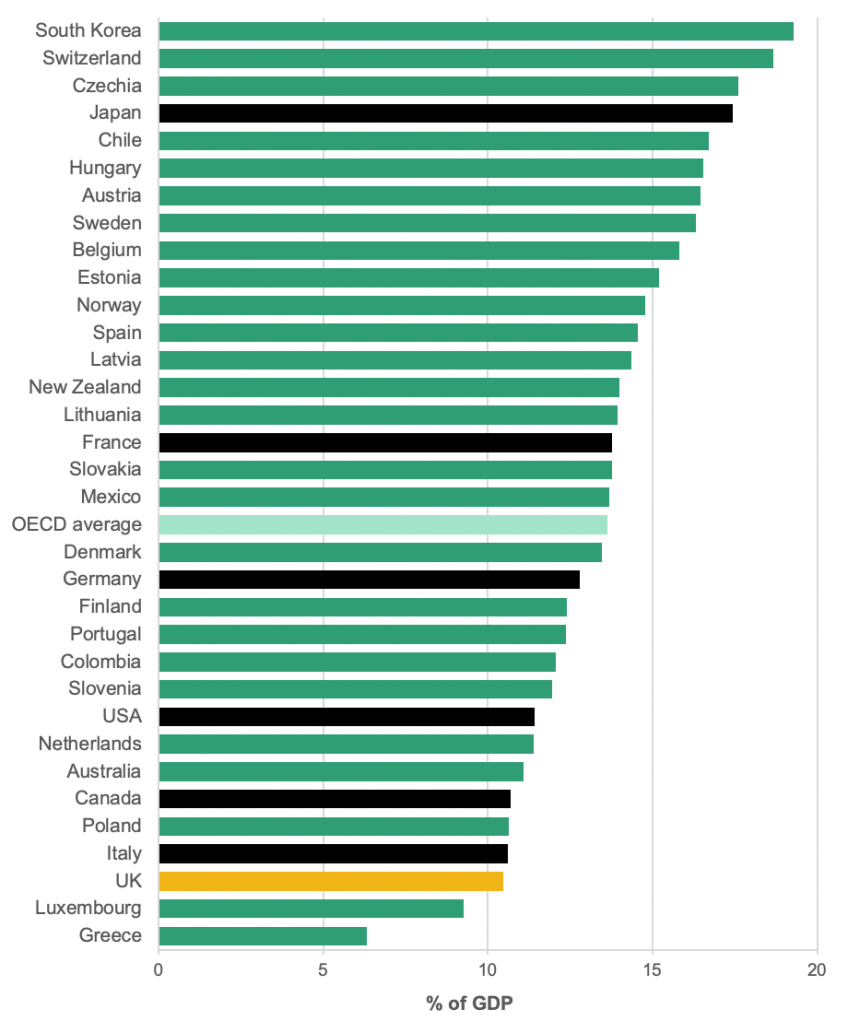

Figure 1. Corporate investment in OECD countries, 2019

Note: Ireland excluded due to the large volatility of its investment statistics. OECD average is the unweighted average of OECD countries for which data are available (excluding Ireland). G7 countries shaded black.

Source: OECD, National accounts of OECD countries: corporate investment, https://doi.org/10.1787/abd72f11-en

Key findings

1. UK rates of corporate investment are among the lowest in the developed world. In 2019 the UK had the lowest level of business investment in the G7 and the third-lowest in the OECD: 10.5% of GDP compared with an OECD average of 13.6%.

2. The UK’s approach to taxing corporate investment is one of extremes. The UK’s headline corporation tax rate (19%) is one of the lowest of any advanced economy. At the same time, however, UK investment allowances are some of the least generous in the OECD. As a result, effective tax rates in the UK (a measure that accounts for both the tax rate and the generosity of allowances) are middling by international standards.

3. Just as importantly, effective tax rates vary drastically between investments. Investing in some assets is penalised much more than investing in others. Meanwhile, investments financed by borrowing can receive substantial subsidies, encouraging firms to take on more debt and to invest in low-return projects that would otherwise be unviable.

4. As inflation rises, these distortions are exacerbated, increasing the premium on achieving genuine structural reform that rationalises the system and reduces such distortions.

5. Kwasi Kwarteng’s dramatic September ‘mini-Budget’ announced the cancellation of a previously planned increase in the rate of corporation tax from 19% to 25%, a decision HM Treasury said would cost a substantial £15 billion a year in forgone revenue (in 2022–23 terms). Alongside this came a (more fiscally modest) increase in the permanent level of the annual investment allowance (AIA), from £200,000 to £1 million, allowing firms to deduct more of their investment spending from taxable profits immediately.

6. Cutting the rate of corporation tax will reduce all of the distortions associated with the tax. However, the tax reduction would be largest for more profitable investments: it would be less effective at reducing the tax on the borderline investments that are most likely to be discouraged by tax. While reducing the rate reduces the distortions to the level, allocation and financing of investment, unless it is reduced to zero, it cannot fully eliminate those distortions.

7. Increasing the AIA, meanwhile, is more cost-effective as a way to encourage investment domestically – it eliminates the disincentive for equity-financed investment in qualifying assets – though not necessarily as a way to increase the UK’s international competitiveness. It also increases subsidies for low-return investments funded by debt – investments that come at a cost to the exchequer but do little for growth.

8. There is strong evidence that, all else being equal, such cuts to corporation tax would be expected to increase investment in the UK. But they will do so only if they are expected to last. Investment decisions are long-term by their nature and the current political environment – and a long history of policy instability – will probably make it harder for the Chancellor to increase investment through the tax system (at least in the short term).

9. While tax matters for investment, it is not all that matters. If interest rates are pushed upwards, or if the UK is seen as providing an unstable environment in which to do business, that could easily outweigh any beneficial effects of lower corporation tax. In other words, corporation tax changes need to be situated within a sensible and credible fiscal framework and broader policy environment if they are to be effective in boosting investment.

10. Only genuine structural reform of how investment is treated by the tax system – as opposed to tweaking individual features – can eliminate distortions to the level, allocation and financing of investment. There is more than one way to achieve this, but it must involve reforming the treatment of debt and equity finance as well as headline tax rates and capital allowances.

11. What is needed is a coherent plan for the future of corporation tax as part of a wider fiscal strategy, clearly communicated, that companies and investors can use as a credible guide to what to expect in the future. There are certainly improvements that could be made. Short of that, some stability would be nice.

Click here to read the full chapter >>>

Click here to read full chapter >>>

Author: Sir Paul Tucker

Summary

Now interest rates are rising, the interaction of quantitative easing (QE) with the Bank of England’s current methods for implementing monetary policy will add to strains on the public finances.

The crux is that QE creates money that goes onto banks’ balances (reserves) at the Bank of England, and those reserves are being fully remunerated at the central bank’s policy rate (known as Bank Rate). Given the outstanding stock of QE (£838 billion), that has effectively shifted a large fraction of UK government debt from fixed-rate borrowing (where debt-servicing costs are ‘locked in’) to floating-rate borrowing (where debt-servicing costs rise and fall with Bank Rate).

Increases in Bank Rate therefore lead immediately to higher debt-servicing costs for the government, leaving the British state with a large risk exposure to rising interest rates, and adding to the already substantial pressures on the public finances. The sums involved are not trivial, potentially running into tens of billions of additional spending on debt interest each year.

Writing for the IFS Green Budget, Paul Tucker examines the nature of the problem, how it has arisen, and the pros and cons of various possible solutions. He argues the current set-up is not technically necessary to operate monetary policy effectively, and so the current predicament could – and arguably should – have been avoided. But as of now, there are no easy options or win–win reforms, with macroeconomic and microeconomic considerations pulling in different directions. The government and the Bank would need to balance several weighty, conflicting things before embarking upon any change.

Abbreviations used in this work are available here.

Report details

- Publisher

- Institute for Fiscal Studies

More from IFS

Understand this issue

Election Special: Your questions answered

27 June 2024

Election Special: The big issues politicians haven't spoken about

25 June 2024

What is the two-child limit in benefits?

27 June 2024

Policy analysis

What are the parties’ plans for benefits and taxes?

24 June 2024

How would the parties’ tax and spending plans affect Scotland and Wales?

28 June 2024

How should we interpret parties’ public spending pledges this election?

23 June 2024

Academic research

6th World Bank/IFS/ODI Public Finance Conference | Driving Progress: Public Finance and Structural Transformation

The role of hospital networks in individual mortality

13 May 2024

Forced displacement, mental health, and child development: Evidence from Rohingya refugees

10 May 2024