Summary

The UK is the talk of the town, and not in a good way. The coordinated sell off in both gilts and sterling reflect growing concerns about both the health of the economic recovery and the viability of the UK’s policy approach. With monetary and fiscal policy still at loggerheads, the risk of further financial disruption remains acute in the months ahead.

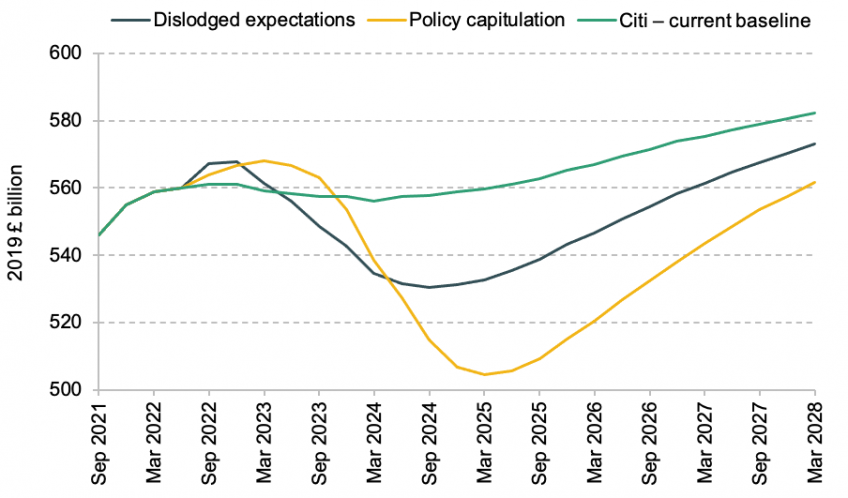

The UK begins in a relatively weak position. The UK is the only G7 economy not to have re-attained its pre-Covid level by the second quarter of 2022. And worse likely remains ahead, with our forecast suggesting that GDP will fall by 0.7% through 2023. The predominant driver of the economic outlook here is the large terms of trade shock. Recent increases in energy prices compound established increases in both food and core goods prices. In each case, this implies price pressures today and crimped incomes tomorrow. We expect that to mean a limited consumer driven recession over the coming quarters, despite additional support.

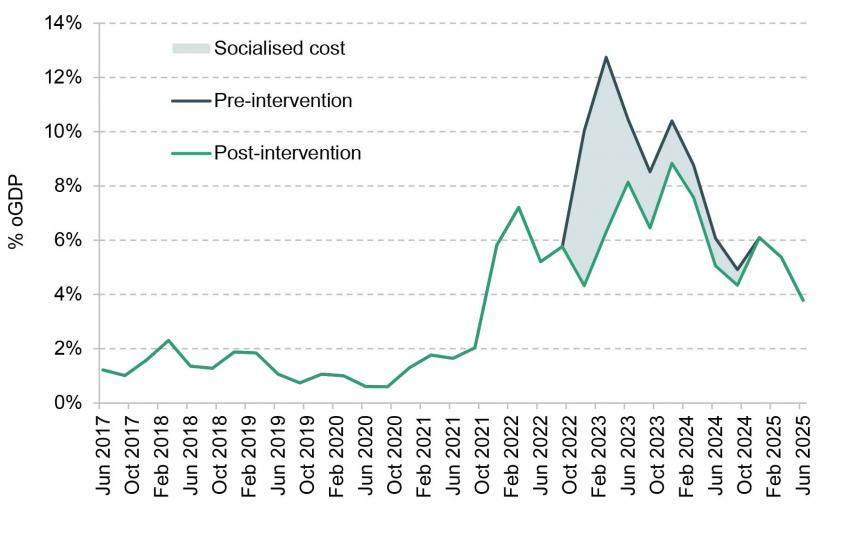

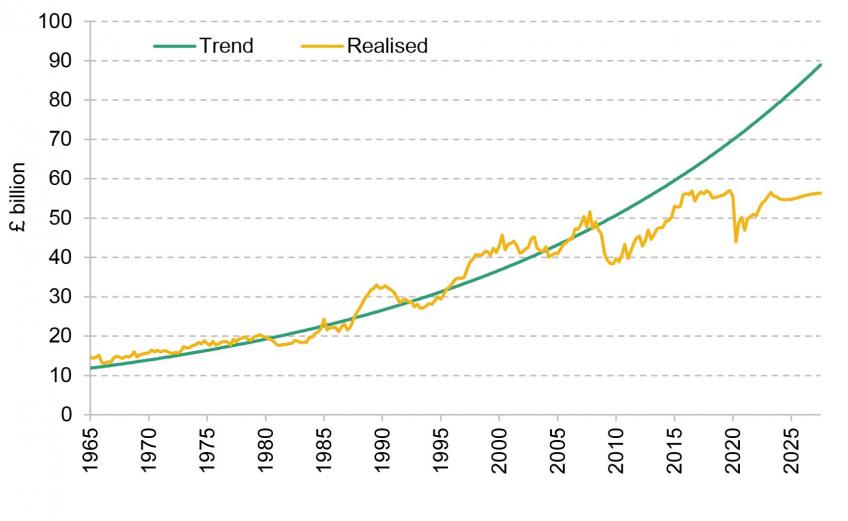

UK – Spending on Gas and Electricity (% GDP), 2017-2025

Notes: Figures are presented here as a share of quarterly nominal GDP. Spending is conditioned on a Citi VAR model of consumption substitution across sectors, alongside current market futures prices.

Source: ONS, Department for Business and Industrial Strategy, Bloomberg LLP and Citi Research.

For now, a weak demand side sits alongside a supply picture that is also heavily impaired. Here, a reduction in labour supply alongside ubiquitous matching challenges mean the UK labour market remains relatively tight. For the Monetary Policy Committee, the concurrence of a tight labour market and very strong imported inflation mean some action is necessary to reduce the risk of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. But this will come at a longer-term cost. While a limited supply recovery seems likely, without carefully targeted support, the risk of material long-term economic scarring is growing.

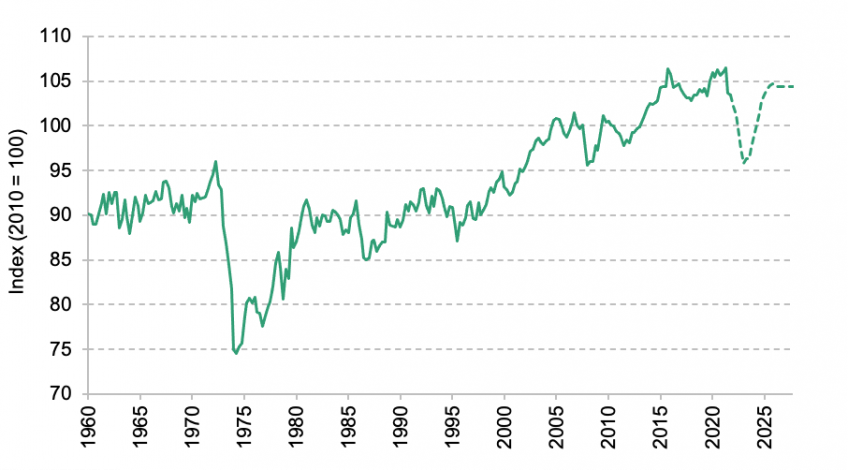

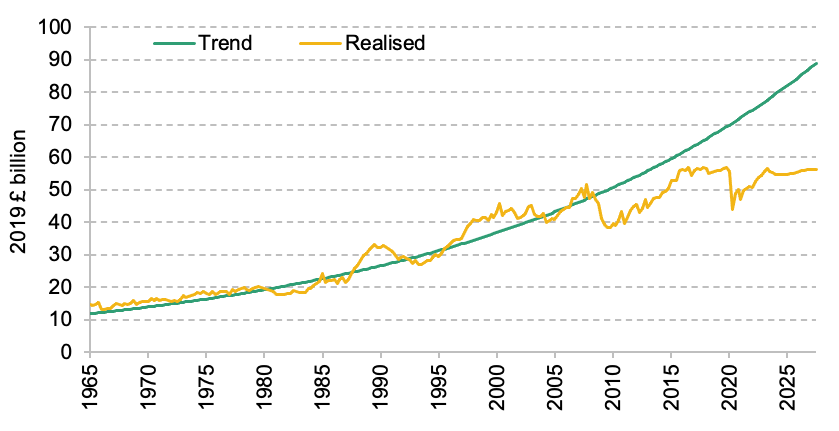

UK – Business Investment (£ 2019 bn), 1965-2027

Notes: Trend business investment growth is based growth between 1965 and 2007.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Overall, policy faces a tricky trade-off between risks of a self-propagating recession on the one hand, and a nominal de-anchoring on the other. Sweeping fiscal stimulus is likely only to mean an outsized monetary response and a weaker long-term recovery. At the same time doing nothing is also far from optimal. The core conclusion we draw from recent experience is that policy would fare better by focusing more directly on managing the supply side of the economy. With structural shocks likely to grow more frequent in the decade ahead, that suggests a structural shift in approach.

Key findings

1. The UK can ill afford any more economic policy mistakes. After a lost decade, the government is right to focus on increasing growth. However, it must do so amidst two tightening constraints. The first is institutional credibility. The second is the need to develop appropriate tools to manage increasingly frequent adverse ‘supply-side’ shocks.

2. In the near term, the key challenge facing the UK economy is the terms-of-trade shock – an increase in the price of imports relative to exports. These effects are boosting inflation, but crimping domestic income. We expect these effects to weigh heavily on demand across both the household and corporate sectors over the coming year. The main upside economic risk remains a sweeping reduction in gas prices. Absent this, however, the UK economy is likely to be structurally poorer. The key policy question is how this loss is allocated.

3. For households, the looming cost shock will hit hardest those least able to bear it. Consumption is likely to be weighed down heavily by looming cost increases. The regressive nature of the shock risks exacerbating the near-term economic impact, particularly as consumer credit conditions continue to tighten. We think this should also argue against policies that transfer away from poorer households to their wealthier equivalents. ‘COVID savings’ also seem unlikely to come to the rescue given the mismatch between their accumulation and those suffering the largest real income shocks. In the medium term, sharp increases in mortgage costs may push any consumer recovery into 2024.

4. The weakness on the supply side of the UK economy is now an urgent concern. While output is 2.6% short of its pre-COVID trend, we estimate current excess demand in the order of 1.4% of GDP. Supply should gradually recover in the months ahead as capital and labour gradually reallocate. Targeted support has a key role to play in aiding reconfiguration and boosting incomes, but sweeping fiscal giveaways risk making a bad situation worse. The risk of a greater long-term scarring seems to be increasing.

5. We expect unemployment to increase from here as demand slows, but only gradually. Labour supply should continue to recover as cost-of-living concerns bite and NHS waiting times potentially begin to fall. However, in the near term, labour hoarding effects suggest redundancies are likely to materialise only slowly. Firm insolvencies may prove a key driver of slack in the near term. And in the medium term, unlike with the Great Financial Crisis, we think more persistent labour hoarding effects are likely to prove only limited.

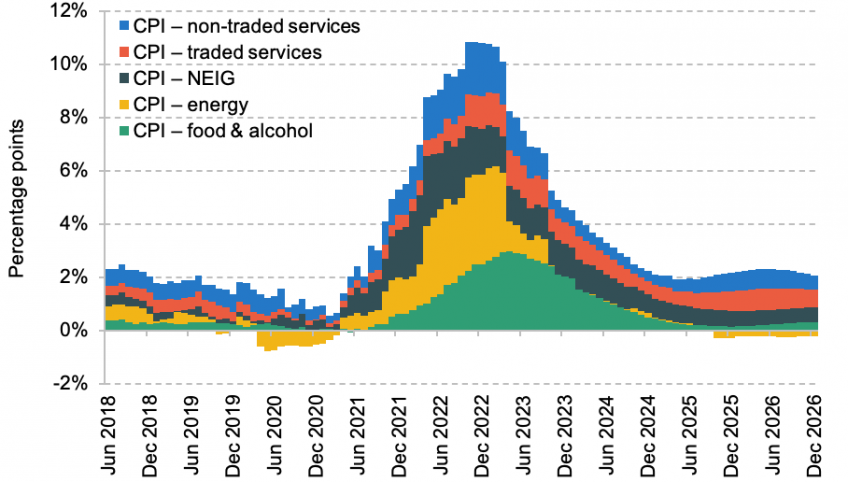

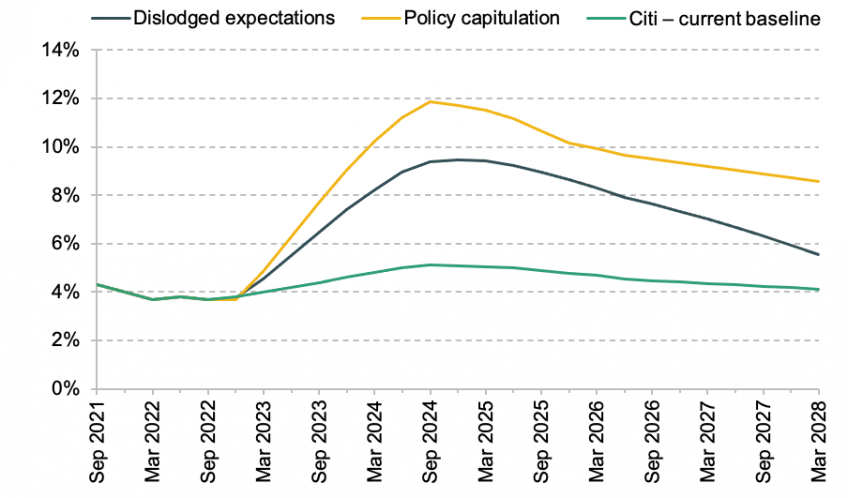

6. Cost pressures remain intense. We expect CPI inflation to peak at 11.8% in the months ahead. While price growth should fall back during 2023, inflation is likely to stay relatively high for a while. And in the interim, the risks of a more nefarious feedback effect into domestic inflation dynamics will remain elevated. For now, we see the risks here as substantial, but contained. However, the sheer level of inflation means uncertainty is particularly high. More monetary tightening is almost certainly needed. De-anchored and expansionary fiscal policy remains the key upside risk to medium-term inflation.

7. The adverse market reaction to the ‘mini-Budget’ was qualitatively different from that to previous events. We think that reflects the now acute conflict between monetary and fiscal policy. In the near term, that calls the UK’s broader institutional credibility into question. In the medium term, it likely means weaker macroeconomic outcomes as the Monetary Policy Committee is forced to ‘overcompensate’ for continued fiscal stimulus. Historically, these shocks have tended to weigh on long-term output as tighter financial conditions weigh on investment.

8. Recent experience shows you cannot effectively manage supply-driven inflation via demand. Policy faces a tricky trade-off steering between the risk of a self-propagating recession on the one hand and the risk of de-anchoring inflation on the other. In our view, a different policy approach is not just desirable, but necessary. The fundamental challenge here stems from the supply-driven nature of the economic shock. Such shocks are likely to occur more frequently than in the past. The current approach risks hampering medium-term growth.

2.1. Introduction

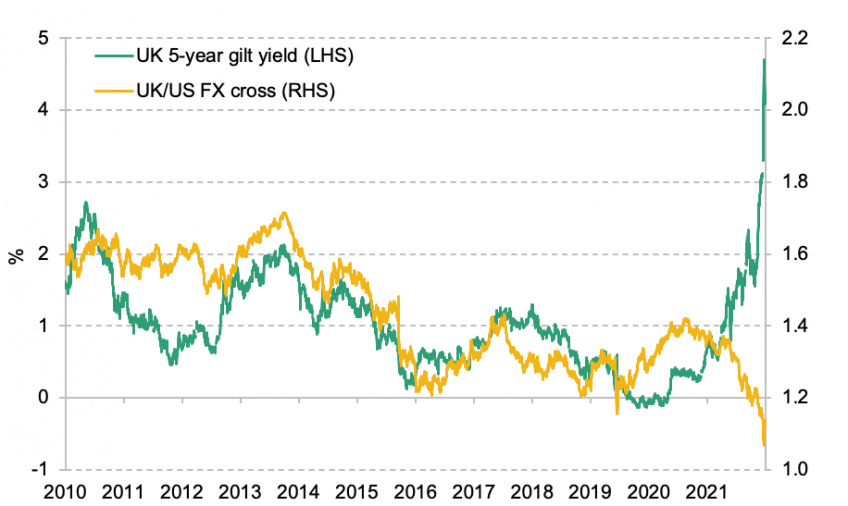

The UK is the talk of the town, and not in a good way. The coordinated sell-offs in both gilts and sterling reflect growing concerns about both the health of the economic recovery and the viability of the UK’s policy approach. With monetary and fiscal policy still at loggerheads, the risk of further financial disruption remains acute. This engenders a downside skew to the risk profile in the months ahead, and risk of weaker long-term economic outcomes.

The UK begins in a relatively weak position. The UK is the only G7 economy not to have re-attained its pre-COVID level by the second quarter of 2022. And worse likely remains ahead, with our forecast suggesting that GDP will fall by 0.7% through 2023. The predominant driver of the economic outlook here is the large terms-of-trade shock. Recent increases in energy prices compound established increases in both food and core goods prices. In each case, this implies price pressures today and crimped incomes tomorrow. We expect that to mean a limited consumer-driven recession over the coming quarters, despite additional support.

For now, a weak demand side sits alongside a supply picture that is also heavily impaired. Here, a reduction in labour supply alongside ubiquitous matching challenges means the UK labour market remains relatively tight. For the Monetary Policy Committee, the concurrence of a tight labour market and very strong imported inflation means some action is necessary to reduce the risk of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. But this will come at a longer-term cost. While a limited supply recovery seems likely, without carefully targeted support, the risk of material long-term economic scarring is growing.

Overall, policy faces a tricky trade-off between risks of a self-propagating recession on the one hand and a nominal de-anchoring on the other. Sweeping fiscal stimulus is likely only to mean an outsized monetary response and a weaker long-term recovery. At the same time, doing nothing is also far from optimal. The core conclusion we draw from recent experience is that policy would fare better by focusing more directly on managing the supply side of the economy. With structural shocks likely to grow more frequent in the decade ahead, that suggests a structural shift in approach.

Below, we begin by discussing the near-term outlook for the UK economy, including the drivers behind the looming terms-of-trade shock, and the implications for households, firms and the UK’s external balances (Section 2.2). We then turn to the challenges around supply and the labour market (Section 2.3), before turning to the outlook for costs and inflation (Section 2.4). We conclude with both a summary of the overall pattern of economic adjustment and the potential alternative scenarios (Section 2.5), before turning lastly to the policy implications and challenges (Section 2.6).

2.2. The near-term outlook

Economic activity has slowed sharply in recent months. As recently as May, much of the soft economic activity data continued to indicate a robust expansion. But in the months since, cost increases across the economy have begun to weigh. Despite considerable fiscal support, we still anticipate a shallow recession over the coming months. Real GDP, we think, will fall by 0.7% year on year (YY) at the trough in 2023Q3. This is already from a relatively weak starting point, with the UK now the only G7 economy not to have recovered to its pre-pandemic level.

Historically, when annual growth falls below 1.5% in a given quarter, this tends to increase significantly the risk of a subsequent further reduction in growth two quarters ahead – on average implying a further reduction of 0.8%.1

For much of the forecast horizon, we do not expect the UK economy to escape this ‘stall speed’.

The risks are increasingly skewed towards a larger and more protracted downturn. On the demand side, that reflects the risk lower incomes could collapse into a period of more protracted weak demand. On the other hand, there is a risk that, by loosening too far, policy could engender a de-anchoring of expectations, much higher rates and a disorderly, inadvertent tightening of financial conditions.

In this section, we focus on the risks to demand. Both households and firms look set to be hit hard by the looming terms-of-trade shock.

For households, we argue below that cost increases in areas such as food and fuel are likely to weigh heavily on aggregate consumption – despite discretionary support. As these effects fade, we also expect higher mortgage rates to constitute a notable headwind, pushing any meaningful recovery into the second half of 2024. Robust balance sheets should provide some support in the medium term. However, household wealth inequality seems to have widened sharply through COVID. This means less resilience. It also suggests a particularly low multiplier on policies that reduce transfers in order to fund tax cuts.

For firms, the primary challenge over the coming months relates to both acute margin compression, and increases in the cost of capital. In both cases, we think that implies only a very gradual recovery in business investment, even from its current low base. The latest data point to large ‘revaluation’ effects as the structure of the economy is beginning to pivot. These write-downs risk casting a longer shadow without more medium-term economic clarity.

The terms-of-trade shock

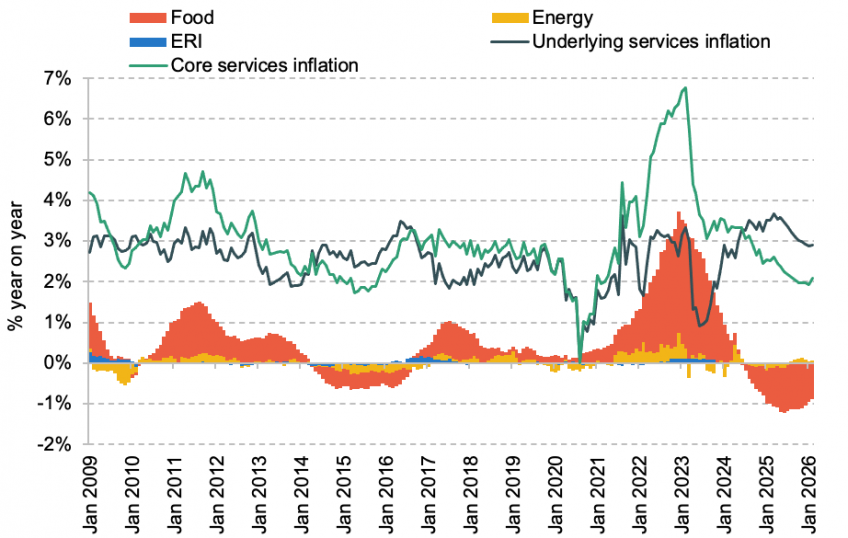

The primary driver behind the near-term economic outlook is a once-in-a-generation, adverse ‘terms-of-trade shock’ (an increase in the price of imports relative to exports). The constituents here are threefold. First, in the latter half of 2021, large increases in imported consumer goods prices drove inflation higher (see Section 2.4). Large increases in energy prices have since increased this further. And, in more recent months, food prices have also picked up sharply. In total, the relative price of exports versus imports has fallen by a little over 3% in the past 11 months, the largest reduction since 2016. Worse, we think, lies ahead (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. UK: aggregate terms of trade, 1960–2027

Note: Terms of trade in this case measured as the ratio between the export price deflator and the import price deflator.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

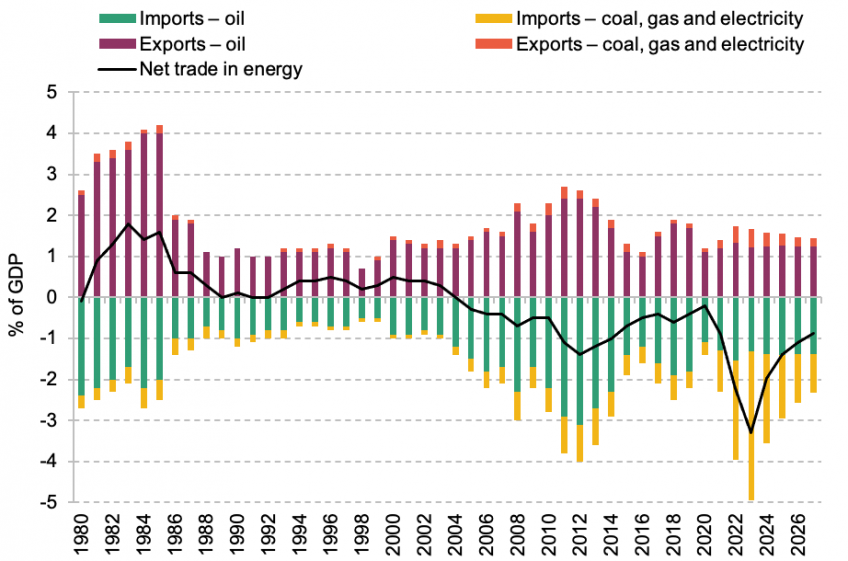

The key drivers from here are likely to be food and energy (specifically gas). Both items are heavily imported. Food imports, for example, amounted to around £50 billion in 2021, while the equivalent exports amounted to just £21 billion (Office for National Statistics, 2022d). Around 50% of UK gas is also imported, primarily from Norway (via pipeline) and Qatar (via LNG) (Donnarumma, 2022a). While the UK has been a net energy exporter in decades past, this ceased to be true around the turn of the millennium. In the years since, the associated energy deficit has grown episodically (see Figure 2.2). The conflict in Ukraine, alongside broader disruption to Russian gas supplies into Europe, has resulted in a very large increase in prices. Compared with the middle of 2021, futures prices for wholesale gas are now four to five times higher for 2023.

Figure 2.2. UK: net trade in non-oil energy, 1980–2026

Note: Figures are presented here as a share of nominal GDP. Figures for 2022 onwards are a Citi forecast.

Source: ONS, Bank of England, Thomas and Dimsdale (2016) and Citi Research.

How will this affect the economy?

In essence, this is a large, net, economic loss for the UK economy. Typically, an increase in import prices adds to inflation in the near term, but then crimps real incomes, demand and domestic inflation thereafter. An increase in energy prices is especially destructive economically. This adds to the relative cost of imports, but it also drives a revaluation between the energy producing and consuming parts of the domestic economy. Income tends to have a much higher multiplier in the latter case than in the former. In the past decade or so, we estimate that a sustained 10–15 pence increase in the price of a ‘therm’ of gas deducted roughly 0.2 percentage points from UK GDP over the subsequent 18 months. Given the 250p increase since the middle of 2021, a simple extrapolation of these effects alone would therefore suggest a hit of around 2.5ppt.

Of course, the reality here is a little more complicated. The scale of the shock means that these simple ‘rules of thumb’ do not likely do analytical justice to the current outlook. Instead, a more in-depth look is required.

In our view, the overall economic impact of a set of price increases such as this depends on three factors:

- the extent to which the consumption of specific (and more expensive) items can fall (in this case, energy and food);

- the extent to which demand imports can be reduced more generally, and the trade balance restored – via offsetting foreign exchange depreciation and trade substitution elsewhere;

- the speed at which the economy can adjust to produce more imported items domestically.

Unfortunately, in each of these three respects, the prognosis for the UK is not good.

Beginning with demand, food and energy are particularly price-inelastic elements of the UK import basket. The change in import volumes associated with a shock to the trade-weighted exchange rate, for example, is especially low among these categories.2

These effects are likely to be compounded by the government’s decision – made for understandable reasons – to cap prices for both firms and households.3

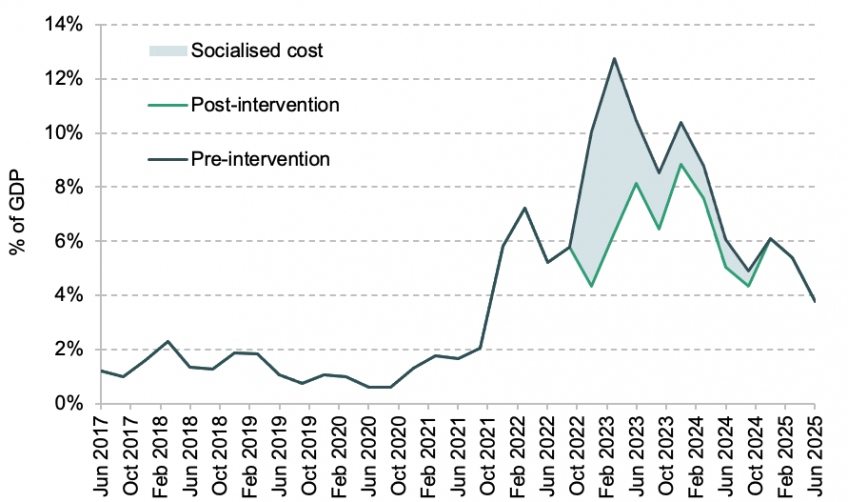

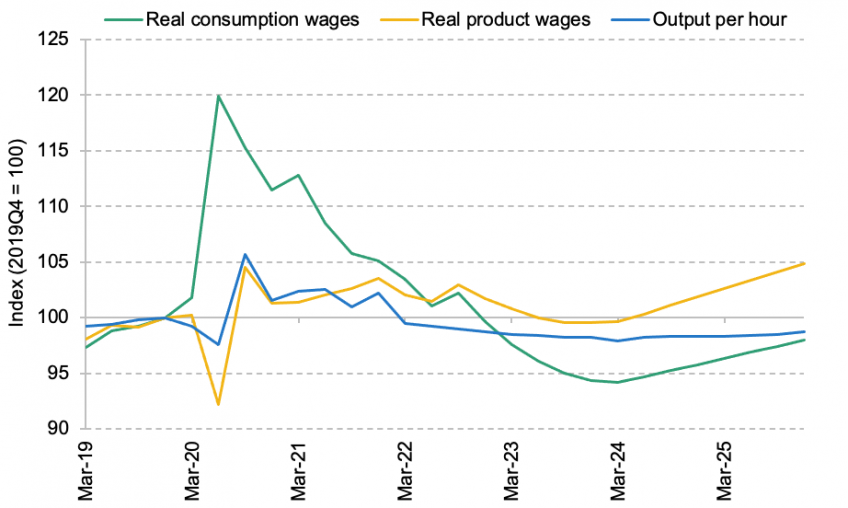

Adjustment is unlikely to be predominantly, or even largely, confined to the UK energy market. Instead, we think the current account deficit for energy alone could widen to over 3.5% of GDP. On the domestic side, we also note that electricity and gas consumption combined could also increase to well over 10% of GDP, from 1–2% in 2015–19 (Figure 2.3).

If macroeconomic adjustment cannot be contained within the energy sector, the burden is likely to shift to the broader trade deficit. The sharp deterioration in aggregate terms of trade will, we think, weigh on both the nominal and real exchange rate, slowing growth and, in the UK’s case, reducing demand for imports.4

Figure 2.3. UK: spending on gas and electricity, 2017–25

Note: Figures are presented here as a share of quarterly nominal GDP. Spending is conditioned on a Citi VAR model of consumption substitution across sectors, alongside current market futures prices. These data are not seasonally adjusted. Forecast runs from 2022Q2 until 2025Q2.

Source: ONS, Department for Business and Industrial Strategy, Bloomberg LLP and Citi Research.

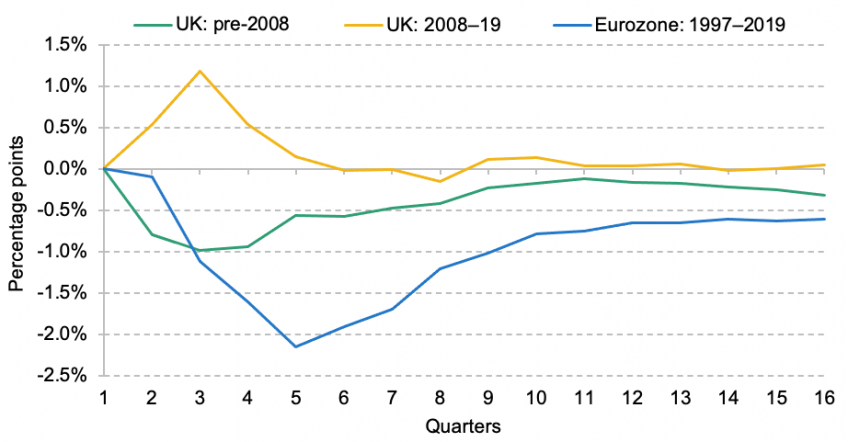

Figure 2.4. UK and Eurozone: impact of exchange rate depreciation on the level of nominal imports, 1997–2019

Note: This figure shows the impact of a one-standard-deviation shock to the exchange rate on nominal imports.

Source: ONS, Eurostat, Bloomberg and Citi Research.

Here, however, we think adjustment could also prove tricky. For one, UK imports overall seem to have become less sensitive to changes in the exchange rate.5 Another important consideration relates to the scale of the domestic ‘tradable’ production versus the current account.6 The challenge for the UK is that the share of tradables in the UK economy remains well down on its pre-Great-Financial-Crisis level.7 The ‘tradable share’ is also now considerably smaller than the overall current account deficit, further complicating any economic adjustment (Calvo, Izquierdo and Talvi, 2003).

In both cases, these arguments suggest domestic output may have to do more ‘heavy lifting’. This means more downward pressure on output. One of the ways this could materialise is via a larger drop in the ‘real effective exchange rate’8 – the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the ratio of UK prices versus those abroad – and an associated drop in domestic demand. While domestic output in the UK is about as sensitive to real effective exchange rate depreciation as, for example, the Eurozone, if the shock is larger this would suggest a larger hit to growth.

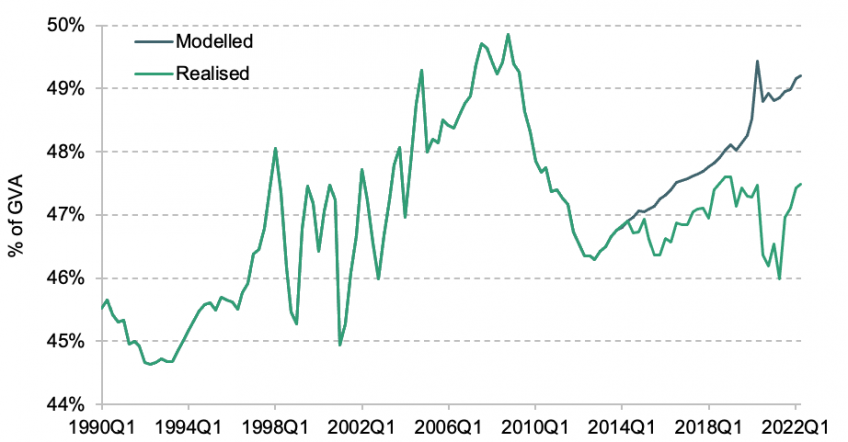

This, however, gets to the nub of the issue. That is, it is no longer clear this kind of shock is sufficient to return the UK economy to rude health. Whereas the Eurozone has tended to recover over time from an adverse real effective exchange rate shock, the UK seems to have experienced some permanent scarring. In part, this relates to some statistical challenges around the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).9 However, when the real effective exchange rate depreciates, this should mean the tradable sector grows as a share of overall GDP. Pre-2008 that does indeed seem to have been the pattern. However, in the period since, the rate of reallocation has fallen (see Figure 2.5).

For now, many of these themes are ‘on ice’. By implementing a cap for both the household and corporate sector, the UK government has stepped in to securitise inflation at scale – absorbing the loss from higher energy prices, and for now preventing these driving domestic prices higher. This is protecting domestic incomes. And if the shock to gas prices does indeed prove temporary, then the widening of the current account deficit should prove only temporary, and broader adjustment unnecessary. This, however, is little more than ‘chancing your arm’, and at macroeconomic scale. If changes do prove necessary, currency depreciation is likely a central part of any associated adjustment. But what the above suggests is that this is no magic bullet. Instead, these effects always leave UK households and firms worse off. These effects are likely to be large, while the slowing rate of substitution between tradable and non-tradable parts of the economy also suggests economic adjustment seems likely to prove considerably more painful than, for example, in the early 1990s, when depreciation alone was sufficient to deliver growth.

Figure 2.5. UK: tradable share of gross value added, 1990–2022

Note: Model here reflects BVAR model of the change in traded share of GVA estimated between 1990 and 2007.

Source: ONS, Eurostat, Bloomberg and Citi Research.

The outlook for household consumption

Households face a challenging few months ahead. Even with significant support, many are still facing up to a large income squeeze.

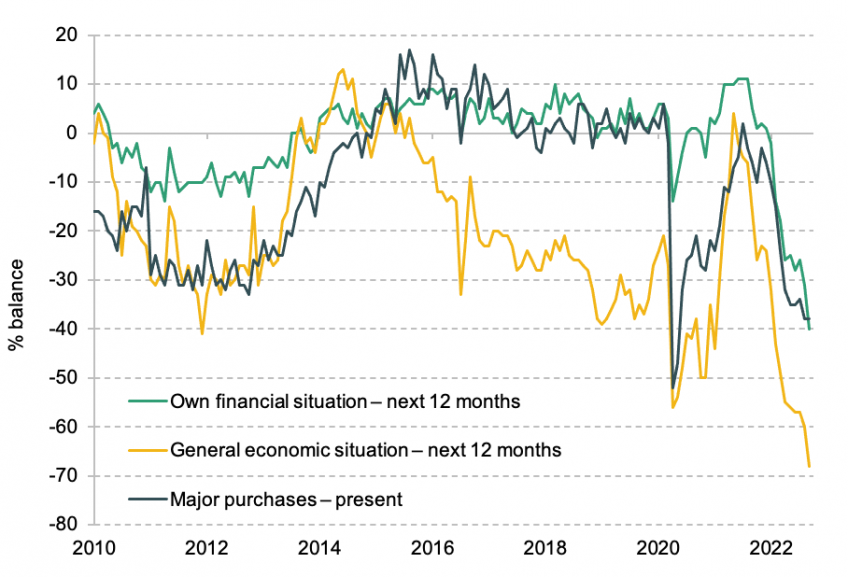

Here, the recent economic data have already showed a softening outlook. In contrast to most downturns, consumer confidence has led the downturn in both the UK and Europe. Many of the price increases associated with the terms-of-trade shock affect households directly. And as increases in food and energy bills have piled up, households’ view of their own financial situation has deteriorated especially quickly.10

Household consumption growth has decelerated from 0.6–0.7% QQ at the end of 2021 to 0.2% in 2022Q2. Retail sales have contracted by 5.5% cumulatively since October 2021. While reductions here were previously offset by a rotation towards consumer services, these effects seem to have faded during 2022. Recent CHAPS spending data showed overall nominal consumer spending still 4–5ppt below February 2020 levels. These data also now seem to be easing.

Figure 2.6. UK: components of GfK consumer confidence, 2010–22

Source: Citi Research and GfK.

As cost-of-living pressures intensify, we expect household consumption to fall by 3% over 2023. Three factors are central to the outlook here:

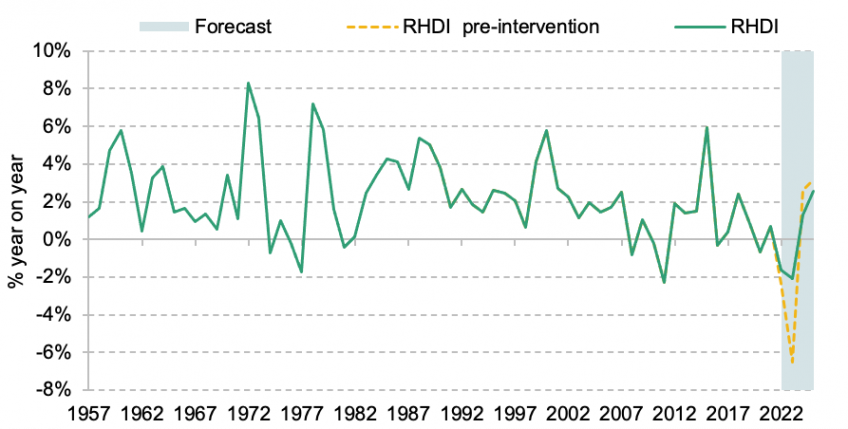

First, even with significant fiscal support, households are already facing up to a crushing set of price increases. As we explain below, wage and employment growth should remain relatively buoyant in the months ahead in nominal terms. However, even with the cap to household energy bills, wage increases are still likely to remain well short of rates of inflation. We think real household disposable income seems set to fall back by a little under 2% on average over 2022 and 2023 (see Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7. UK: real household disposable income (RHDI) growth, 1957–2025

Note: The difference between the pre-intervention and current RHDI reflects measures announced since the March Spring Statement.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Breadth, as much as depth, of the price increases matters here. We count challenges on five fronts:

- Household energy bills. Ofgem confirmed a 54% increase in household dual-fuel energy bills in April, with the standard tariff increasing £693 from £1,277 to £1,971. Even with additional support, this still left UK households absorbing £19.5 billion in additional household energy costs. A further £500 increase associated with the price cap increase in October will still leave households a further £14 billion worse off in annualised terms – although these effects should be initially offset by the previously announced £400 rebate. In early September, 48% of households reported they were struggling to pay their energy bills, versus 35–40% in 2022H1.11

- Fuel prices. Despite recent reductions, diesel and petrol prices are still both up 33% and 26% respectively compared with the same month in 2021. The impact of these increases on spending is compounded by compositional normalisation as the economy has reopened – with spending on commuting and other day-to-day travel returning to its pre-COVID range in volume terms. Price increases here over the past 12 months amount to around £330 in additional annual spending for the average UK household. Nominal spending on fuel reached twice the level observed in February 2020 in July, according to data from Revolut (Office for National Statistics, 2022b).

- Food prices. Food prices have already contributed to the squeeze on household incomes. Kantar data show the typical UK household is paying £571 more for food annually than it was this time last year,12 with the latest ONS Opinions and Lifestyle Survey noting this has been the primary driver of the crunch on incomes to date (with 95% of respondents noting food was now significantly eating into household incomes).13 We expect food inflation to accelerate to roughly 17% by 2023Q1, up from 10.8% in August. This is primarily owing to higher food, commodity, energy and import prices.

- Housing costs. House prices have grown sharply so far during the pandemic, with the latest Nationwide data pointing to roughly a 10% annual increase over the last few months. We expect these increases to feed into higher rental prices over 2023.

- Lagging benefits uplift. Last, many of those on the lowest incomes have also been struggling with a relatively low increase in core benefit payments. UK benefits are generally uprated by CPI in September of the previous year. This meant a 3.1% increase from April. However, this is juxtaposed by an increase in annual CPI of 9.9% in August – a 6.2% real terms fall. Though some of these effects were also offset by the large share of the May support package paid to those on means-tested benefits.

In an economy whose median post-tax household disposable income is roughly £30,000, this is a crushing squeeze. Compared with the UK’s longer-term economic history, this would still be among two of the weakest years on record, one after another, although the price cap, the £15 billion May package and the further £22 billion in personal tax cuts do reduce the risk of what would have been a much worse outlook (Figure 2.7).

Second, we think the scope for dissaving is likely to prove limited. Household income of course does not translate one-to-one into consumption. Given the large accumulation of saving during the pandemic, the hope for some time has been that some of this accumulated saving could be used to smooth over the looming shock. Unfortunately, we think the scope for dissaving is limited. We expect household saving rates to fall to 7.2% at the trough, versus 3.5% in the latest Bank of England estimates.

As we noted in last year’s Green Budget (Nabarro, 2021), if widespread dissaving is to materialise, one of three arguments will have to hold: (1) deferred demand; (2) changes in credit constraints; or (3) a large improvement in the net asset positions of households, and robust forward-looking optimism. While we think there is some evidence of deferred demand effects over the summer, many of these effects now seem to be fading.

Figure 2.8. UK: household saving rate by income decile, 2020–22 (forecast)

Note: These data measure income minus expenditure, divided by income. They are therefore not directly comparable to the headline household saving rate. These data are a forecast based on Citi’s household income decile model. The data show the deviation in the savings rate from the 2012–18 average. All of these data are Citi forecasts.

Source: ONS and Citi.

Instead, we think that if dissaving is to accelerate, this will relate primarily to changes surrounding credit constraints. The issue here is while household savings accumulated during the pandemic were extensive, they were heavily skewed towards those at the upper end of the income distribution. Our modelling would suggest net household saving became increasingly regressive (see Figure 2.8) – backing up survey data suggesting a strong positive association between income and ‘active’ wealth accumulation (Leslie and Shah, 2021). These higher income groups are suffering a smaller real income squeeze since less of their budgets are spent on energy and food. This suggests a more limited ongoing boost compared with a conventional baseline.

There are several signs of this in the recent data. The share of households claiming they cannot manage an unexpected £850 expense has been climbing (Office for National Statistics, 2022a), for example, while the overall level of outstanding deposits has remained steady. This suggests that these cash balances are in the ‘wrong place’ macroeconomically speaking. In other cases – for example, towards the middle of the income distribution – there may be scope to borrow on the back of improved housing equity. But this also speaks to the wider issue: while the use of deposits is relatively limited, the use of debt to try to smooth over recent price increases does indeed seem to be on the rise. The ONS Opinion and Lifestyle Survey shows the share of households now leaning on credit to cover day-to-day costs has increased 7 points since the end of 2021, with these data still on an upward trajectory. The Bank of England consumer lending data show similar increases in credit card balances.14

While there is scope for consumer debt to grow further, the issue in our view is that as monetary policy is tightened, the availability and cost of credit are likely to make this more and more difficult. This means a mechanical widening in credit spreads. Affordability metrics in many parts of the unsecured consumer credit market are coming under strain. The latest data from the Bank of England’s Credit Conditions Survey suggest one of the most abrupt tightening episodes for unsecured consumer credit,15

even as demand is picking up. This, we think, is likely to limit the scope for further dissaving.

Overall though, net household balance sheets have improved through the pandemic. In comparison with the pre-COVID trend, the total increase in household deposits, as well as the reduction in unsecured consumer credit, amounts to around 7% of GDP. Looking at the total change in household net assets since the start of 2020 overall, we think the ‘real’ net increase amounts to 14.2%. Although net increases seem to have been concentrated almost exclusively among those in the top half of the income distribution (Leslie and Shah, 2021).

Dissaving is likely to offset some of the adverse shocks looming in 2023, if to a limited degree. One notable question here is whether dissaving could provide a more persistent tailwind further out. We do expect a small net boost from these effects in the latter years of the forecast. In the near term, uncertainty regarding the persistence of some of the recent price increases we think will reduce the incentive to dissave (Bunn et al., 2017).16

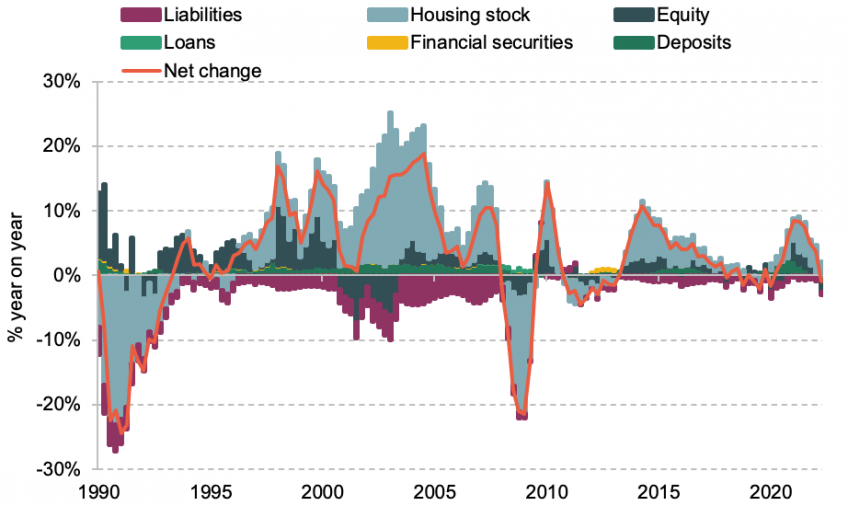

And with more of these positive wealth effects driven by increases in real asset values, we think the marginal propensity to consume out of such increases will be low (Figure 2.9). But unlike the GFC period, households are unlikely to go through a painful and protracted period of deleveraging. And in the medium term that should provide a small relative boost.

Figure 2.9. UK: growth in ‘real’ net household wealth, 1990–2022

Note: Real household wealth is derived by deflating total nominal household wealth by the consumption deflator.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

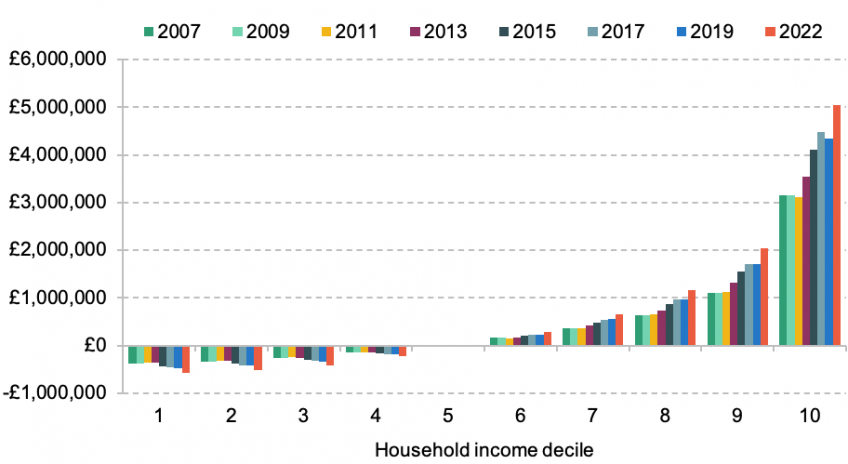

One implication of the argument above is that household wealth inequality has likely widened further through the pandemic (see Figure 2.10). Among lower-income households, we think a limited bout of borrowing over the coming months is likely to worsen further their net assets position. For higher-income households, the boost associated with the pandemic years seems likely to be preserved. With shocks to areas such as food and energy prices likely to grow more common, widening inequalities here reflect a worrying erosion in macroeconomic resilience. Improving the wealth share of those outside of the top income decile is likely essential to allow these shocks to be effectively weathered in the years ahead.

Figure 2.10. UK: real net household wealth by income decile, compared with median, 2007–22

Note: Findings are based on the ONS Wealth and Assets Survey. Deflated based on CPI inflation for the given income group. Chart shows real household net wealth minus the median in the same period. 2022 is a forecast.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

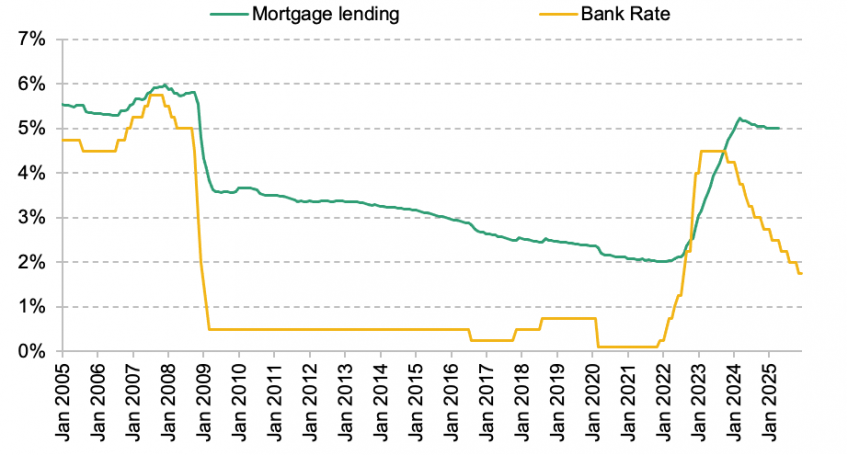

Third, we expect higher rates to weigh meaningfully from 2023H2. The Monetary Policy Committee has engaged in the fastest monetary policy tightening since Bank independence. It seems certain more is to come (see Section 2.6). As we explained above, we think changes here are already feeding into the availability of riskier consumer credit products. But pass-through into mortgage costs also seems likely to drag.

Compared with previous tightening cycles, the impact on household finances is attenuated by the shift towards fixed-rate mortgages. Whereas these made up just 40% of all outstanding mortgage lending in the early 2010s, today the equivalent proportion is roughly 85%. However, whereas in other economies where mortgages can be fixed in long durations (10 years +), in the UK the vast majority (95%+) of all mortgage lending is fixed at either a two- or five-year duration. Increases in Bank Rate therefore still feed through into household debt servicing costs relatively quickly.

Over the coming months we see this as an increasingly important headwind for household consumption. With Bank Rate set to increase to 4.5% in the months ahead under our central forecast, we expect quoted mortgage rates on two- and five-year fixed-rate tariffs to increase by roughly 5ppt versus their trough in early 2020. This would suggest an annual increase in debt servicing of roughly £8,500 for a household with the average outstanding mortgage balance of £181,000.17

Mortgaged owner-occupiers make up just over 30% of households – meaning a smaller aggregate impact on demand overall. But even so, this would still suggest a multi-thousand-pound increase in average household costs.

These effects will not materialise all at once. But while some households took the opportunity to refinance at the start of 2022, there is still a large glut of fixed-rate mortgage tariffs that are likely to roll off over the coming months. These reflect the surge in activity following the introduction of a stamp duty holiday in 2020. We expect the effective interest rate on outstanding mortgage lending effectively to double over the coming months from a trough of 2.0–2.1% in the early part of 2022 to 5.0% at the start of 2024, weighing on household disposable income by roughly £1,600 on average per household.

Figure 2.11. UK: effective interest rates, 2005–25

Source: Bank of England and Citi Research.

In order to meet these higher debt servicing burdens, we think the hit to consumption will be relatively large, constituting a further headwind through 2023 and 2024.18

Despite the robust position of better-off households, we also expect UK house prices to fall by roughly 7% by 2023Q3. Last month’s cut to stamp duty will provide some offsetting support to prices, if not activity. But we think rates at these levels will be sufficient to drive some forced selling among owner-occupiers, particularly those in the middle of the income distribution.

We expect these effects to be compounded by vulnerabilities in the private rented sector. In recent years, mortgage lending within the buy-to-let sector has made up 10–15% of all new mortgage advances.19

Given the growing share of the private rental sector overall (HM Government, 2021), we see some potential for forced selling here too. For the first time, landlords may have to manage with mortgage rates notably above average annual rental income (as a share of the property value). Recent restrictions surrounding tax deductibility on mortgage interest income add to the risks.

Combined, this outlook suggests any meaningful recovery in household consumption is likely some years away. While, as we have noted in previous years, it is always dangerous writing off the UK consumer, we think the headwinds here are likely insurmountable. In the near term, price increases associated with the terms-of-trade shock seem likely to weigh. From the second half of next year, increases in mortgage costs are likely to become the key headwind. More policy support could offset these effects in the near term, though as we discuss below that would likely only push the downturn further out.

We should stress that such a protracted period of consumer weakness has been a rarity for the UK, certainly since the 1950s. In the near term, the implication of the household saving discussion suggests that any efforts to boost incomes for lower-income households would have a particularly high multiplier. From a macroeconomic perspective, cutting benefits in order to finance cuts to direct taxes seems likely to only weigh on the outlook.

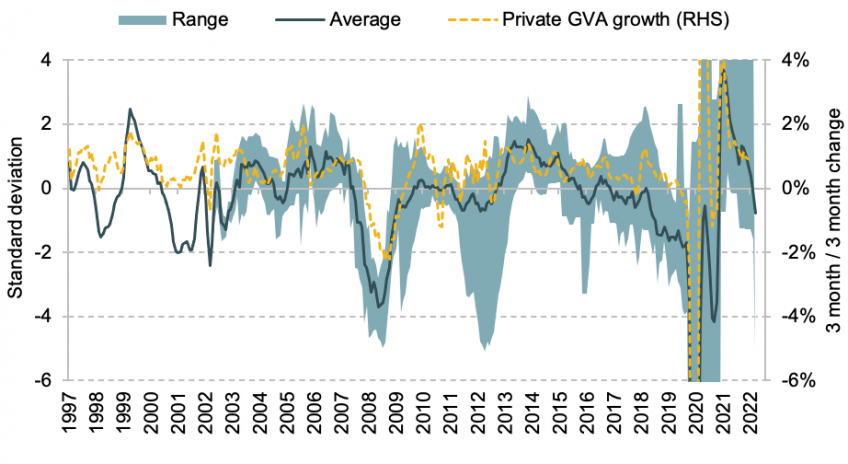

The looming challenge for firms

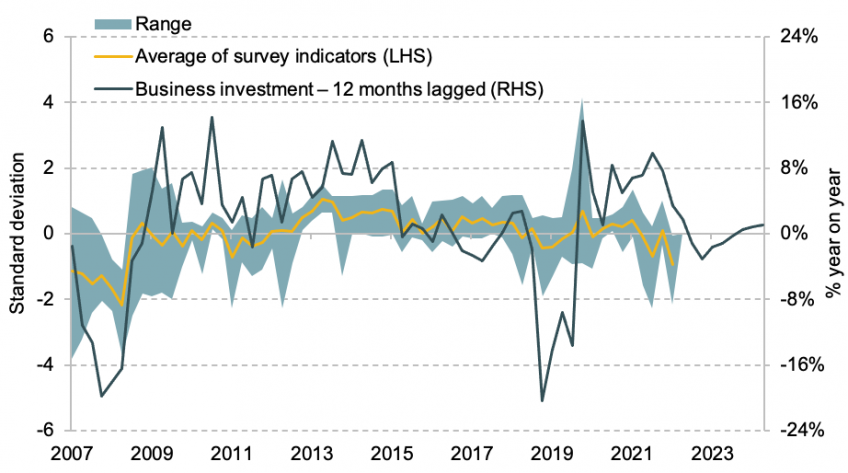

While consumer sentiment has deteriorated sharply in recent months, the business equivalents have generally proven more resilient. The latest business sentiment surveys are on average 0.8 standard deviations below their long-term average – soft, but substantially better than the record lows observed for consumer confidence. Indeed, some had suggested that business investment could take over responsibility for driving the recovery, even as consumption begins to slow (Bank of England, 2022a). This would have some notable advantages. After years of consumption-driven growth, some recovery here is likely necessary if any economic recovery is to prove sustained.

Note: Each series is normalised over the 2010–19 period. The swathe shows the range of soft activity indicators.

Source: Citi Research, ONS, CBI, BCC, BRC, IHS Markit, Deloitte CFO Survey, Lloyds and Nowcasting Economics.

Unfortunately, we think the relative resilience in business sentiment primarily reflects a handful of transitory effects. In particular, intense supply disruption during COVID had resulted in record backlogs across both the consumer- and business-facing sectors. The latest data show these are now decelerating. Weakening demand within the consumer-facing economy is broadening. New work balances within the Purchase Managers Index are now at a 20-month low. Business optimism has also fallen to its lowest level since May 2020.

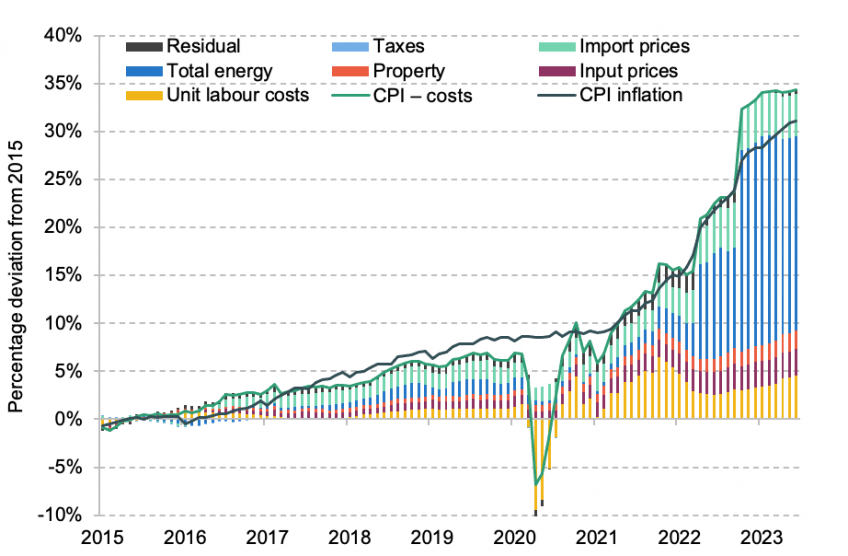

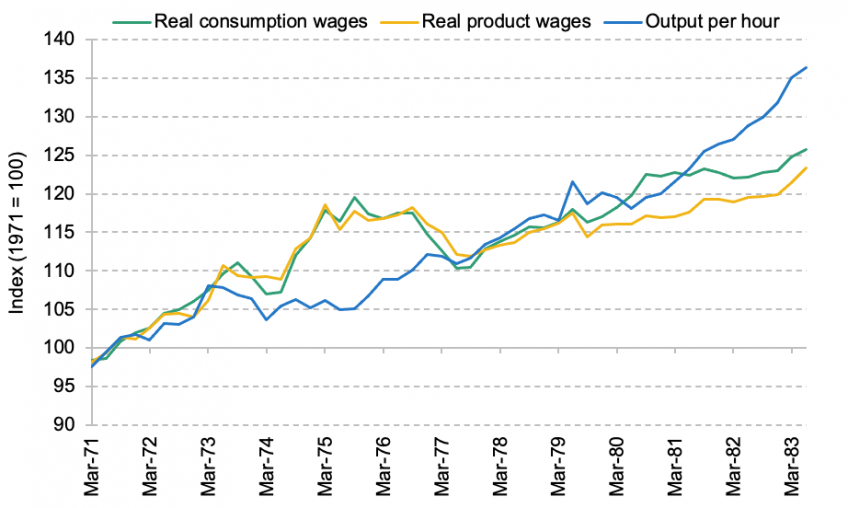

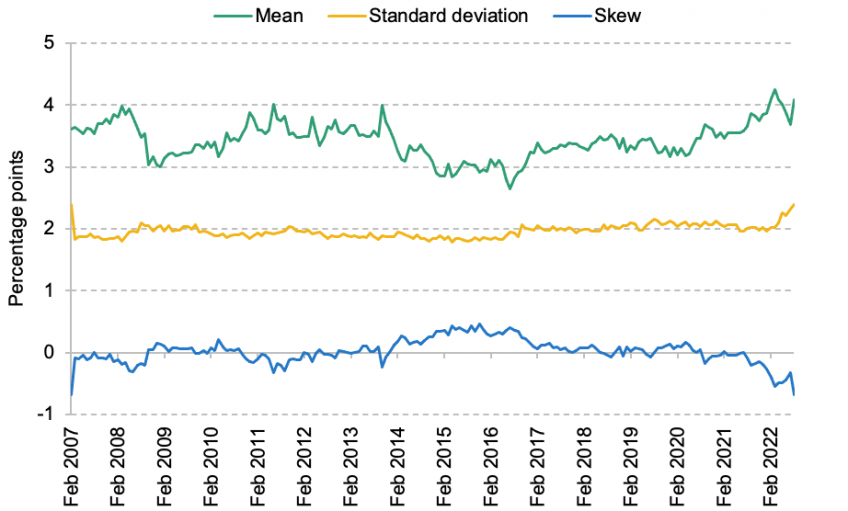

The outlook for investment merits special attention in our view (see Figure 2.13). Productive investment has been the key blemish for the UK economy not just since 2016, but even prior to that – where rates of investment have increasingly diverged from historical user costs of capital. In part, these trends reflect (1) a large substitution into intangible investment (Haskel and Westlake, 2018) and (2) evidence in some cases of capital rationing – especially in the period post-GFC. But even so, some residual ‘under-investment’ seems to remain (Bailey et al., 2022). Unfortunately, near-term prospects are likely to remain weak. We expect investment to be weighed down by three headwinds:

Figure 2.13. UK: business investment, 1965–2027

Note: Trend business investment growth is based on growth between 1965 and 2007. Forecast period is from 2022Q3.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

First, margins are likely to come under extensive and sustained pressure. Firms face challenges on two fronts. First, cost pressures are likely to intensify further. While government support announced to date should offer firms considerable help, electricity remains a particular issue.20

Recent increases would still suggest total corporate energy spending increasing from around £5 billion per quarter in 2021 to £10 billion per quarter through the end of this fiscal year, and potentially to £20 billion when support is unwound. This sits alongside a range of other imported cost pressures.

On the other hand, softening demand also means firms are increasingly struggling to pass on further cost increases to customers.21

So far, dynamics here have been relatively healthy. Within consumer-facing sectors, output prices have roughly kept pace with their input equivalents. While this has been relatively asymmetric across sectors (Bunn et al., 2022), firms have generally reported stronger pricing power than usual.22

But broader signs of stress have begun to emerge in recent months. Within the PMI data, for example, the spread between input and output prices widened to a record extent through the start of 2022. Output price growth has also moderated seven months in a row. PPI inflation – charged to firms – has continued to accelerate among manufactured goods, even as CPI inflation has eased back.

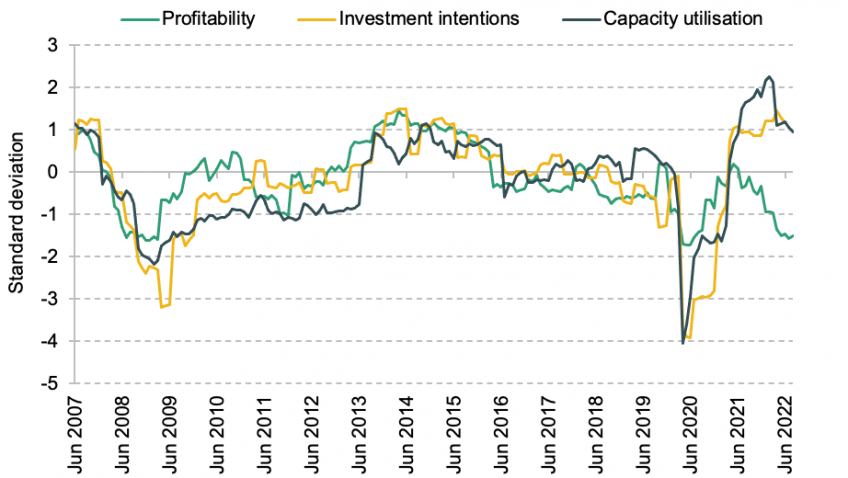

The latest survey data show profitability expectations among their weakest on record (see Figure 2.14). Our own models would also suggest gross operating surplus falling by 1ppt by the middle of next year. This need not in all cases be a mark of low investment, especially when capacity utilisation rates are high – as they are today. However, the impact on investment tends to hinge on business optimism, and the associated growth backdrop. For example, within the CBI Service Sector Surveys, there is little clear correlation between costs and investment intentions, but during periods of softer growth the correlation tends to be much stronger, and negative. In the current circumstances, we would expect a reduction in profitability to have a negative impact on investment.23

Figure 2.14. UK: survey indicators of capacity utilisation, investment and profitability, 2007–22

Note: Data are normalised over the 2007–22 period.

Source: Citi Research, Bank of England, BCC, CBI and Deloitte.

Second, firms are facing higher financing costs. We expect Bank Rate to increase to 4.5% in the months ahead. Markets have priced in an even larger increase. Whereas households have insulated themselves somewhat via the shift towards fixed-rate mortgages, corporates remain heavily exposed. Some shorter-duration money market and floating loans have been refinanced at longer, fixed terms. The issue is that that is not sufficient to compensate for legacy financial agreements. As a share of bank lending, therefore, over 75% of the outstanding balance is still payable on a floating rate. This amounts to just under 41% of all corporate debt. Among SMEs the share is similar – around 70% – despite the fixed-term lending under the Bounce Back Loan Scheme.

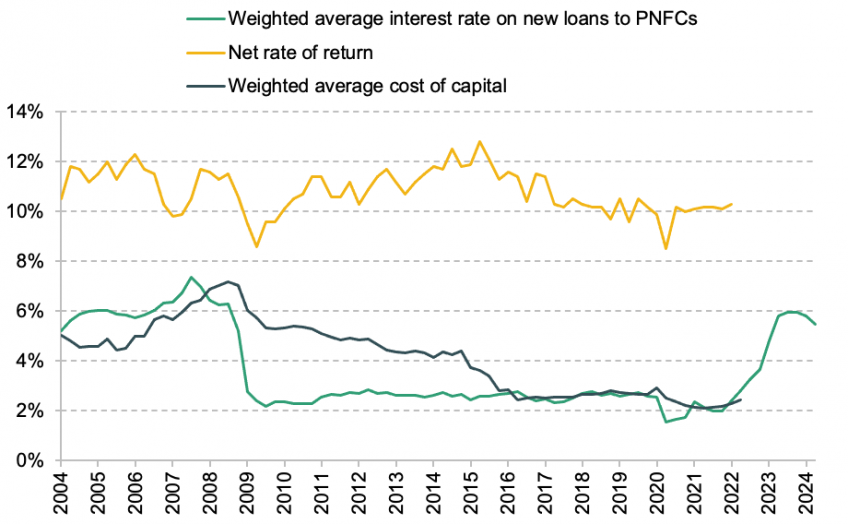

Higher rates are therefore likely to bite hard. Lending rates on outstanding non-financial corporate sector lending have already increased by 90bp since March 2021 – a much larger increase than that on outstanding mortgage lending. Recent volatility on both equity and corporate lending markets suggests the increase in the total weighted average cost of capital is likely somewhat greater. The latest survey data show firms are now beginning to adjust their plans in the face of higher rates. The proportion of services firms, for example, noting the cost of capital as a constraint in investment decisions is up 9 points on average compared with the end of 2019 (CBI, 2022). We expect this to weigh on investment through 2023 and 2024.

Figure 2.15. UK: net rate of return and cost of capital, 2004–24

Note: PNFCs are private non-financial corporations. Net rate of return is measured here as gross operating surplus, net depreciation and revaluation, as a share of total assets.

Source: ONS, Bank of England, Cunliffe (2017) and Citi Research.

One important issue here has been a notable widening between the cost of capital for many firms and the rate of return on investment (see Figure 2.15). Some have argued that in the years to come this ‘additional risk premium’ could begin to narrow (Haldane, 2021). We are less sure. Many of the factors that contributed to these effects, including growing economic tail risks (Vlieghe, 2019), and broader increases in economic uncertainty, remain as salient today as they were in the years post-GFC.

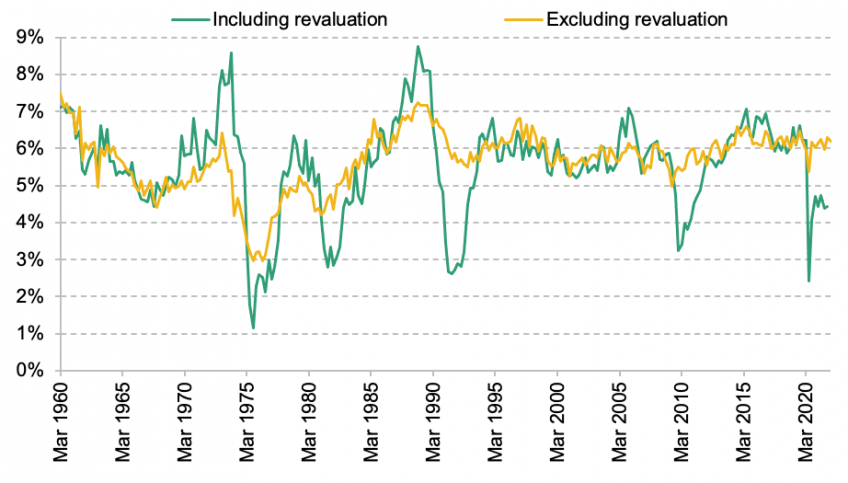

Third, and last, we think firms are also likely paring back their investment plans in light of a weaker medium-term economic outlook. One notable feature of the current data is the marked divergence between the ‘effective rate of return’ on current capital assets including and excluding valuation effects (Figure 2.16).24

What this effectively means is that the future productive potential of many assets is being written down. While such divergences are common during sharp downturns, in general the two series tend subsequently to converge. However, write-downs seem to be increasing, rather than beginning to fall back. This points to a more structural revaluation.

Figure 2.16. UK: effective rate of return including and excluding revaluation, 1960–2022

Note: The effective rate of return is calculated as the gross operating surplus divided by the overall stock of capital. Revaluation effects are calculated in the conventional fashion, based on the approach of Hall and Jorgenson (1967).

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Why does this matter? There are two issues here. The first, and more direct, concern is when assets are written off this can weigh directly on business investment – which is calculated as a net measure. The second, and perhaps more interesting, implication relates to firms’ willingness to invest. Usually this is a function of returns, as well as interest rates, expected depreciation and the expected change in the value of the asset. If asset prices are falling, this can make firms considerably more cautious. However, this also points to the potential for better investment outcomes if policymakers are able to separate expected returns from a weak contemporaneous reality. For now, the UK seems locked on a more pessimistic trend.

Figure 2.17. UK: survey indicators of investment and lagged business investment growth, 2007–24

Note: Data normalised over the 2007–22 period. The swathe displays the range of soft indicators. Forecast period is from 2022Q3.

Source: Bank of England, CBI, Deloitte, ONS and Citi Research.

We should stress here the near-term outlook is of course not pure doom and gloom. In the very near term, investment is likely to be supported by the 130% ‘super deduction’ implemented by former Chancellor Rishi Sunak.25

Alongside the 50% first-year allowance, we think these changes alone imply a reduction in the user cost of capital of 1.5–2.0ppt. Ordinarily, this would suggest an increase in investment of 10–15%. With the offsetting increase in the rate of corporation tax now dropped, we expect this policy to offer a stronger near-term boost to investment in March, before softening back thereafter. Several specific supply constraints – especially surrounding labour – should also ease.

However, investment itself is also relatively energy intensive. Recent increases in energy prices are therefore likely to weigh. And given the UK government has also chosen to prioritise consumption over investment, we think that also implies further weakness on the investment side. With investment in 2022Q2 still 5.7% below its pre-COVID (2019Q4 level), we expect this level to be surpassed only now in 2026. This is likely to leave the UK in a worse medium-term position.

Is the current account sustainable?

The external side of the UK economy is now an urgent concern. As we noted above, the government’s response to the current energy crisis seems likely to weigh further on the current account. In Q1 of 2022, the external deficit already widened to 7.2% of GDP – a new record. We expect a further widening to over 8% in the months ahead, before moderating thereafter. A due dose of humility is required here. The UK trade data are volatile at the best of times. And the most recent estimates are especially uncertain. The current account deficit for Q1 alone was revised by 2.8ppt.26

However, in our view, the underlying data here remain very weak.

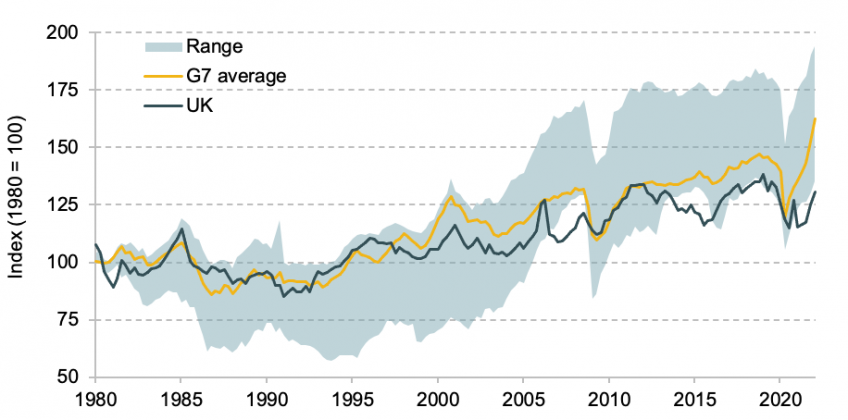

As in 2017, UK trade has once again failed to capitalise on a buoyant global environment through 2021. Instead, total goods exports to both EU and non-EU countries are around 15–20% off G7 averages. A synthetic control unit that seeks to control for the industrial composition of UK trade would suggest UK trade is lagging its pre-Brexit/COVID benchmarks by around 25–30% overall.27

Differences between UK and EU trade data suggest volumes are likely to continue to fall somewhat – with the UK still a conduit for goods produced elsewhere in the world into continental Europe. Compared with G7 peers, the UK is becoming a less open economy.

Figure 2.18. G7: total trade, 1980–2022

Note: Range here reflects G7 performance excluding the UK.

Source: ONS, national statistical offices and Citi.

Overall volumes here should continue to recover somewhat. The combination of both Brexit and COVID seems to have generated a series of compounding disruptions. This seems to be especially true of imports where border disruption and reported delays have been especially severe. In the months ahead, we expect these transitional difficulties to continue to fade.28

As volumes normalise, we expect the associated recovery to drive a further widening in the UK trade deficit.29

Among exporters, there seem to be signs of structural adjustment. A larger share of exporters – for example – report a more persistent shift away from EU markets. This is corroborated by Freeman et al. (2022), who have shown a sharp fall in the number of firms exporting to the EU in 2021 not matched by fewer UK residents importing. In our view, these structural changes are a key signal. Exiting international markets can be expensive. When temporary disruption adds to trading costs, firms tend to respond by reducing trade volumes overall. This is the pattern observed among imports. But when a shift is more structural, this tends to drive acute changes in composition. As demand and supply conditions normalise further in the years ahead, we think this implies persistent downward pressure on net trade.

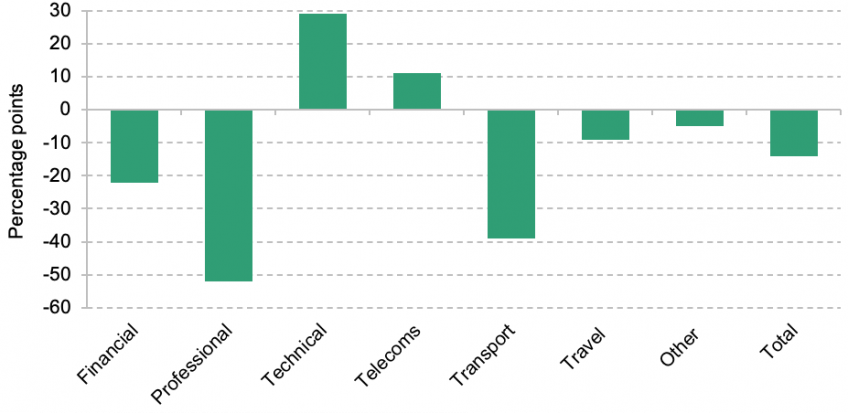

One area of particular concern is exports of professional and financial services. COVID has weighed on services trade in general in recent years – with services imports and exports lagging their pre-COVID levels in July 2022 by 21% and 13% respectively. However, looking under the surface, the drivers in each appear quite different. Services imports in particular tend to be more heavily focused in areas that depend on the movement of people. In total, 45% of all UK services imports are via so-called mode 2 and mode 4 of services trade which depend on the movement of people (versus 12% of services exports). This we think points to a stronger recovery in imports as conditions normalise. In financial and professional services in particular, much of the relative weakness has been driven by weaker export growth to the EU (Barfield, 2022). With regulatory divergence set to gather steam in the years ahead, these effects seem likely to worsen.

Figure 2.19. UK: changes in services exports (difference in growth 2018–21 between EU and rest of world)

Note: The value here shows the percentage point difference in cumulative growth 2018–21 between services exports to the EU and those to the rest of the world.

Source: ONS, Barfield (2022) and Citi Research.

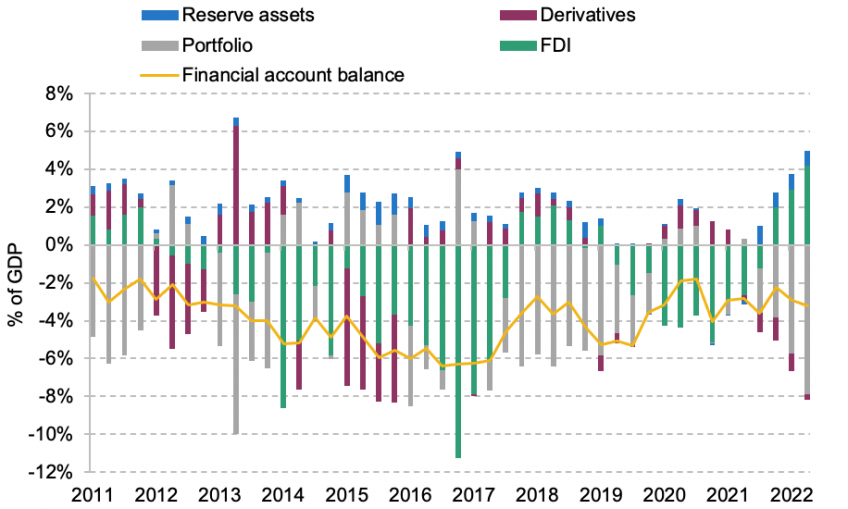

A large and persistent trade deficit opens a second question – namely how is the UK likely to fund itself?

In recent years the UK’s net investment position has continued to deteriorate (now at 123% of GDP). Unlike in the years pre-GFC where the UK generally recycled portfolio flows into foreign direct investment (FDI), these processes have ceased – at least in net terms. The UK has instead been increasingly using inflows to fund its own domestic consumption.

In the months ahead, we think the UK may find this increasingly difficult. Unlike in the years post-GFC, the UK will also have to secure funding in a context where the share of incoming FDI is much lower, and competition for capital across the transatlantic economy is likely to be considerably greater. The outlook here is directly linked to the outlook for government borrowing, with international portfolio inflows increasingly focused on the purchase of government debt.

This, we think, is a more structural concern for the UK. While the UK has run large current account and fiscal deficits for some time, the scale of these seems set to grow. Most of the UK’s net liabilities are focused in portfolio debt instruments. That means that should the UK economy shrink, there is no fall in the nominal value of the instrument. That shifts more of the burden of adjustment onto the exchange rate.

Figure 2.20. UK: net financial account, 2011–22

Note: Data show four-quarter moving averages.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Neither of these factors means the UK is at immediate risk of a ‘sudden stop’ with respect to capital inflows. However, they highlight the risks. With a large fiscal and current account deficit, UK monetary and fiscal credibility are likely to be under particular scrutiny. These effects point to another interdependence, namely that associated with domestic household saving. If dependence on foreign capital is to be reduced, the easiest way of doing so would be to encourage more household saving. However, as we noted above, that would come at the expense of near-term growth.

2.3 Supply, capacity and adjustment

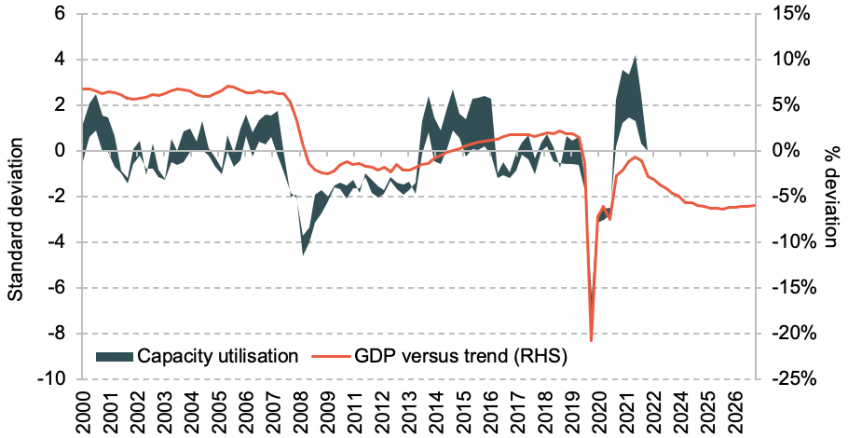

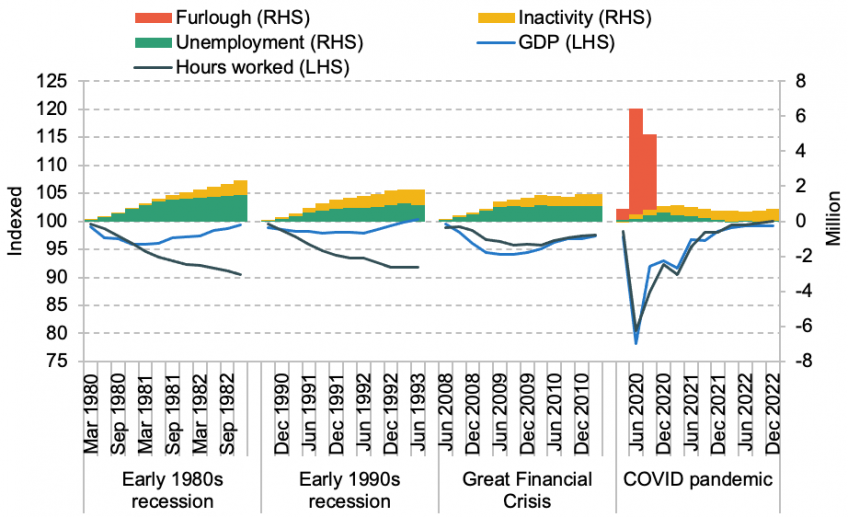

The UK has been subject to a series of large, successive supply shocks. By virtue of both their scale and the fact they have occurred in quick succession, the impact has been especially severe. While UK GDP is currently 2.6% below its pre-COVID trend, we therefore think the economy is currently around 1.4ppt above capacity (see Figure 2.21). In the months ahead, we expect adjustment to accelerate, driving a gradual if meaningful recovery. However, we see substantial challenges ahead with respect to both labour and capacity mismatch. With rates of economic reconfiguration likely to accelerate, we think these challenges constitute a more structural challenge for economic policy over the coming decade.

Figure 2.21. UK: GDP and capacity utilisation, 2000–26

Note: The GDP deviation is taken as the gap between realised GDP and the level implied by medium-term trend growth, divided by the latter. The trend series is based on output in 2014, where the deviation is zero. The capacity utilisation measure is normalised across the period as a whole. Forecast period is from 2022Q3.

Source: ONS, Bank of England, CBI, BCC and Citi Research.

As we explain in Section 2.6, we think this necessitates a change in policy approach. While the previous section highlights the risk of doing too little, this section highlights the risk of doing too much – at least via conventional means. Simply stoking demand risks aggravating the underlying supply challenges, worsening inflation. Policy must support incomes where essential. But this also suggests efforts to foster effective reconfiguration must be more central to the UK’s policy response. This requires supply-focused policy. For now, the current fiscal discussion remains a long way away.

Mismatch: challenges for both labour and capital

While the composition of demand across the UK economy has normalised significantly, we are still working through a series of structural economic changes. Today, these relate in part to efforts to adjust to higher energy prices. They also reflect changes associated with a sharp depreciation in the exchange rate, and legacy changes associated with both Brexit and the pandemic. While rates of sectoral reallocation have decelerated in recent quarters, these remain around double the rate seen just before the pandemic, and we see potential for some modest further acceleration in the months ahead.

Ordinarily, structural economic change should not play a major role in conventional macroeconomic discussions. Economic reconfiguration is assumed to be ubiquitous and continuous, but largely irrelevant for policymakers thinking about the overall stance of fiscal and monetary policy. One sector may grow at the expense of another, but the net result for macroeconomic aggregates should be relatively limited. The problem when these effects are both large and sudden is that such an assumption is clearly false. Some employees and capacity are fixed in place – at least for a period. That weighs on supply in the interim (Broadbent, 2021a).

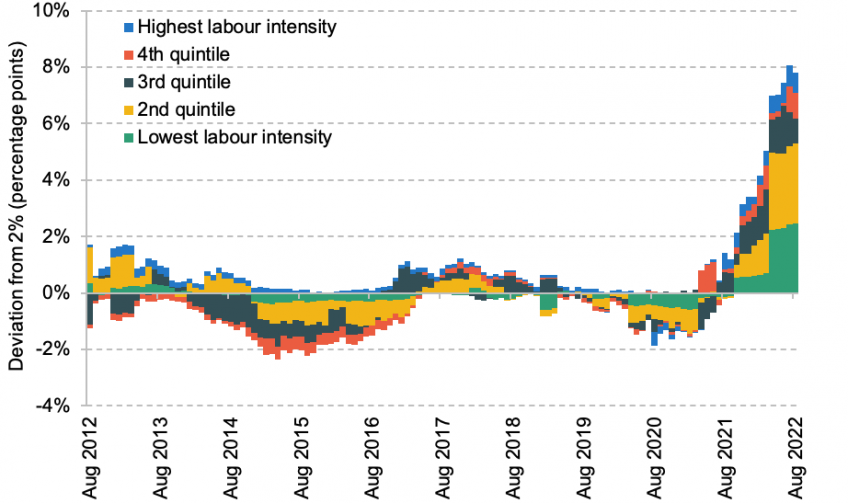

One way of examining these effects is to look at dispersion in price growth across sectors. As we explained in last year’s Green Budget (Nabarro, 2021), reallocative challenges would tend to mean prices rising faster in certain parts of the economy as strong demand clashes with warped supply. Earlier in the pandemic, there was clear evidence for these effects within output prices – with price growth through 2021 heavily focused in those areas with the strongest demand (Bunn et al., 2022). These effects tend to add to inflation overall as downward nominal rigidities preclude offsetting reductions elsewhere.

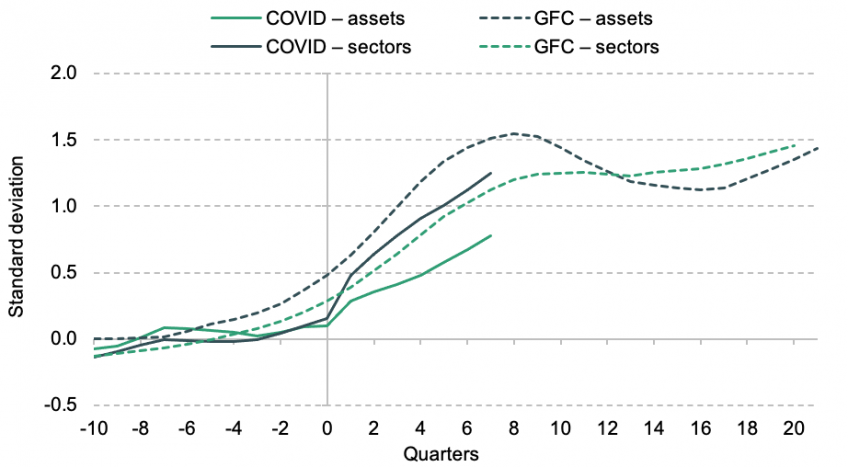

While these effects have begun to ease, we think there is still some evidence of the same ‘reallocative’ challenges both in the labour market and across various capital services.

On the capital side, price dispersion has increased sharply since the start of the pandemic (see Figure 2.22). Here we look at user costs across two-digit industrial sectors. Since 2020Q2, there has been a marked increase in dispersion in capital costs across sectors of the economy – more so than in the aftermath of the GFC (Broadbent, 2012). This, we think, points to some misallocation of capital. Of course, there is a question of how easily capital can be effectively redeployed. Looking instead across different assets, dispersion has also grown. But the scale of price dispersion here is actually somewhat less than in the aftermath of the GFC. This offers hope that capital can be reallocated, not scrapped.

Figure 2.22. UK: capital services costs across various capital forms, GFC and COVID

Note: On the horizontal axis, 0 reflects 2008Q3 in the case of the GFC and 2020Q1 in the case of COVID. The measure here is based on the normalised change in capital services user costs compared with the pre-GFC or pre-COVID period. The cross-sectional dispersion of these normalised series is shown.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

In comparison with the GFC, perhaps the starker difference is within the labour market. While during the GFC there was a moderate pickup in wage dispersion – primarily owing to a sharp drop in income within financial services – across the economy overall growth remained subdued, but relatively uniform. In part that reflected that the shock initially affected those at a higher skill level disproportionately. That eased any associated matching challenge.30

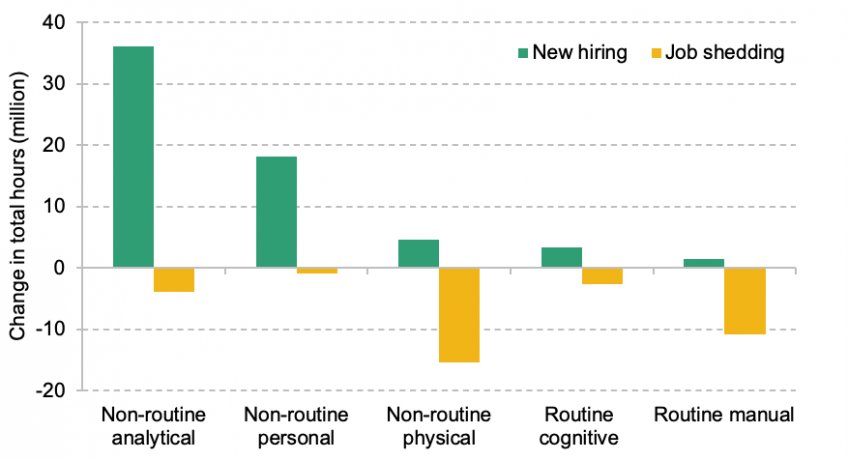

Outcomes since the pandemic remain a little more disrupted. Dispersion in wage growth has jumped sharply across both sectors and regions. Increases have been greater in those areas enjoying stronger demand. In Figure 2.23, we look at the total changes in hours worked between 2016 and the end of 2021 by occupation. We then decompose those changes by the average task composition.31

This provides an indication of whether the task composition of the jobs that have been lost is similar to the task composition of those that have been created. Demand for non-routine tasks seems to be greater, and we see a skew towards human capital intensity. These data in our view suggest the potential for a more lasting mismatch issue. Wage growth has been strongest in capital-intensive sectors since 2020.

Figure 2.23. UK: task composition of job shedding versus new hiring, 2016–21

Note: These data show the change in the total number of hours worked between 2016 and 2021, broken down by task of those roles that have disappeared and those roles that have been created.

Source: Citi Research, ONS, Resolution Foundation (2022), O*NET and Acemoglu and Autor (2011).

This we think poses a more lasting policy challenge for the UK economy. In particular, whereas post-GFC the UK could adjust through differential and lower wage growth, the challenge now is to build new skills in order to plug these matching issues. This task is likely made more urgent by lower rates of immigration, with many firms previously filling these ‘skills gaps’ from overseas.32

Despite the skills-intensive nature of the recovery, labour market outcomes in recent years have been characterised by a further acceleration in ‘de-skilling’. This suggests some need to generate not just more but different skills.

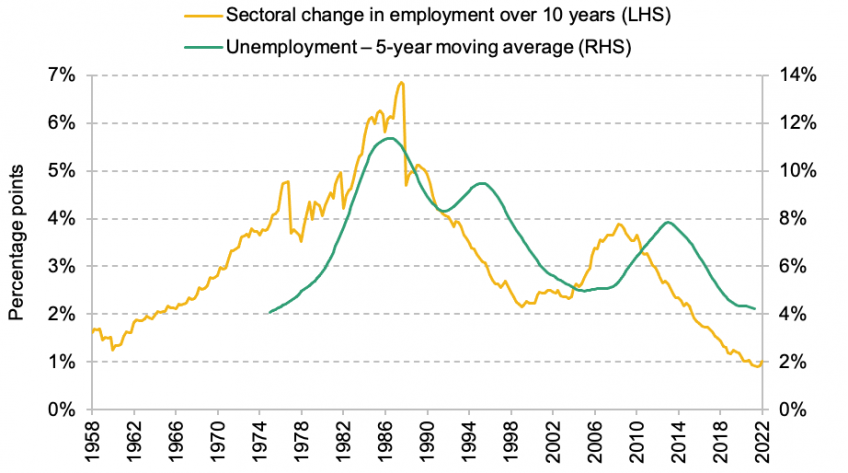

Further supply shocks likely lie ahead. After two decades in which reconfiguration rates have proven mercifully low, this is likely to pose a challenge for labour market policy. Historically, this has placed much greater weight on how effectively institutions are able to reallocate workers in demand sectors (Wells, 2022). The UK has a mixed record with such policies. Notable reconfigurations through the late 1960s did little to add to unemployment – in part reflecting the intensive work of Employment Exchanges. By contrast, outcomes in the 1980s and early 1990s were considerably worse.

Figure 2.24. UK: rate of sectoral change in employment, 1958–2022

Note: Sectoral reallocation here is measured as the weighted average of the change in employment share. Measure based on Chodorow-Reich and Wieland (2020).

Source: Citi Research, ONS, Bank of England, and Thomas and Dimsdale (2016).

On the capital side, these effects mean the orderly management of insolvency is likely to become more important. In some respects, the UK is relatively well positioned here. A relatively lightly regulated economy in both product and labour market terms is helpful.33 The UK also has relatively accommodative insolvency laws, making it easier to recognise and reallocate where economical (Adalet, Andrews and Millot, 2017). Post-GFC, factors such as the weakness of banks’ balance sheets was seen as an impediment to effective reallocation, with fewer banks willing to recognise when firms were likely unviable, and their loans subsequently written down. These effects have been less severe through COVID – reflecting widespread macro-prudential reforms over the past decade. Although in recent months we think there has been some evidence of ‘diabolical sorting’ that could cause concern (Acharya, Lenzu and Wang, 2021). There may also remain some issues with the recognition of Bounce Back Loan losses (Leslie, 2022).

However, rates of business dynamism (firm formation and closure) have fallen in recent years.34 One factor that could increasingly weigh in reallocation rates is the increase of intangible capital. These assets have grown significantly as a share of the UK’s capital base. They also often constitute firm-specific capital – meaning they are harder to reallocate in a case of insolvency. This should not mean losses are not recognised ultimately. However, it does increase the risk financial firms are slower in winding down. And in recent years it does seem that intangible-intensive sectors have contributed most extensively to the slowdown in productivity.35

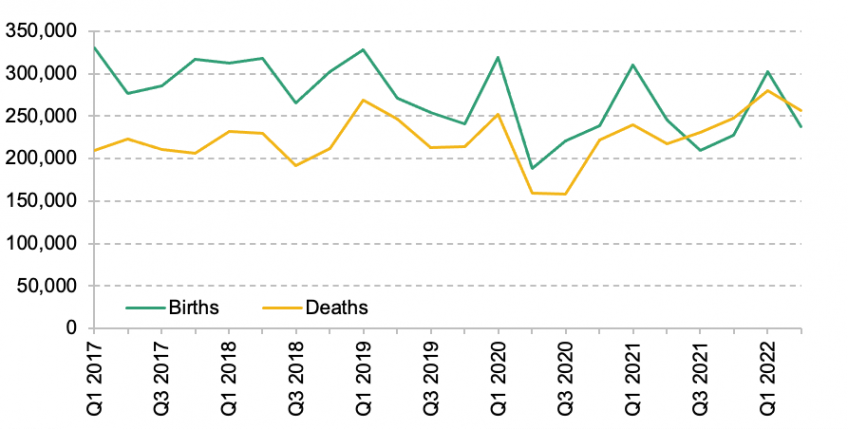

Will labour supply stay low?

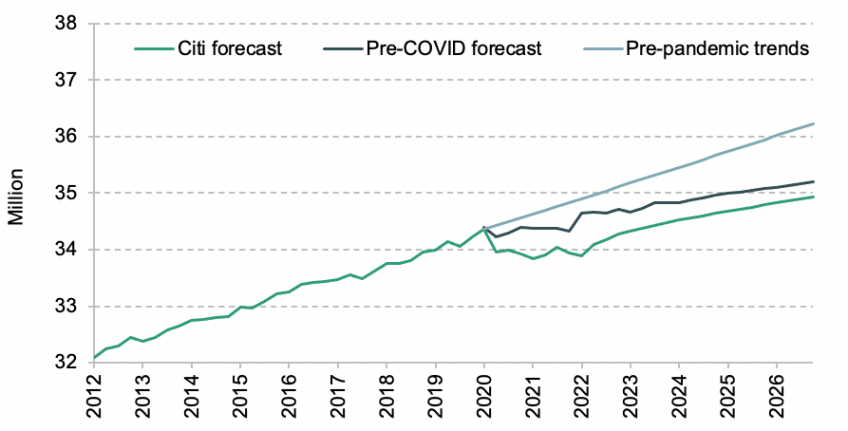

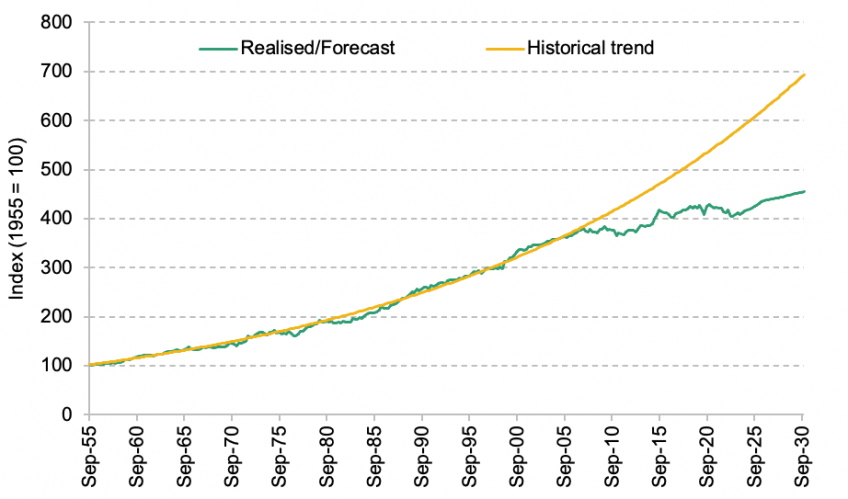

The UK also faces a more specific associated issue – a shortage of labour. While the UK is not alone in seeing participation drop post-pandemic, the effects do now appear especially sevThe UK also faces a more specific associated issue – a shortage of labour. While the UK is not alone in seeing participation drop post-pandemic, the effects do now appear especially severe. Total labour activity is roughly 900,000 (2.4%) below where it would be had growth observed since 2012 continued (Figure 2.25). Total hours worked are even weaker – around 3.7% below, versus a shortfall of 2.6% for GDP. ere. Total labour activity is roughly 900,000 (2.4%) below where it would be had growth observed since 2012 continued (Figure 2.25). Total hours worked are even weaker – around 3.7% below, versus a shortfall of 2.6% for GDP.

Figure 2.25. UK: workforce, 2012–26

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

Over time, the impact of these changes should attenuate. A shortfall in total labour supply of 3.7% would usually mean long-term scarring of 2.1% in the medium term as production rebalances. In reality, the contribution versus our pre-pandemic baseline is a little less, around 1.0ppt, as we had already assumed a reduction in EU migration would weigh on workforce growth in the medium term. But when these shocks occur quickly, the supply side of the economy struggles to rebalance. This weighs more heavily, at least for a time.

A more important question for the outlook here is whether this hit to supply does indeed prove permanent. We think there are some grounds for optimism.

First, we think the size of the workforce should recover some of the losses that have emerged so far during the pandemic. We have been encouraged by the pickup in non-EU migration. Visa approvals in total were up 50% in 2022 above levels in 2019–20, with skilled applications up 66%.36

Strong EU applications to the UK’s settled status scheme suggest further EU net emigration is likely only limited – a finding corroborated by the ONS’s initial estimates. We also see potential for further increases in non-EU immigration, even beyond our 2019 assumptions. These primarily relate to the decision to reintroduce the ‘Skilled Worker Route’ – a substantially more liberal system than the Tier 2 visa it replaced.

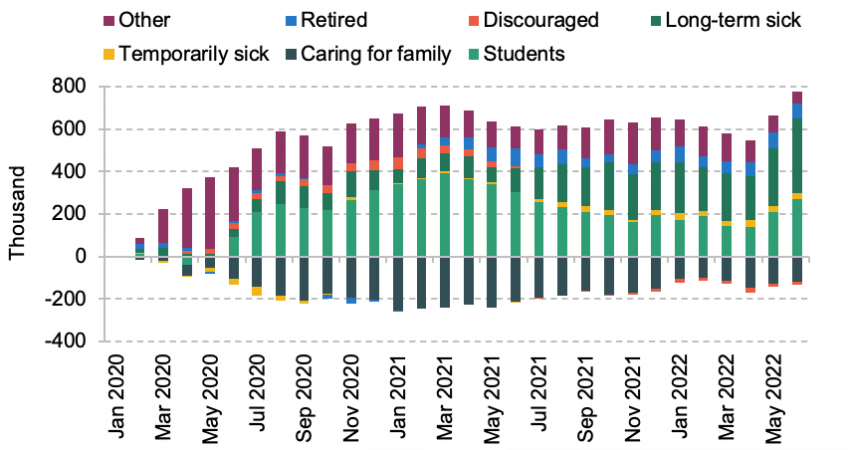

Second, we think participation should also gradually recover. Since the start of the pandemic the increase in inactivity has been concentrated among two groups: (1) older workers between the ages of 50 and 64 (who have added a net ~400k inactive) and (2) (younger) working-age men (~180k). These effects are generally limited to those who claim they currently do not want to work. The most common reason is either long-term sickness (~460k) or retirement (~80k). Despite an offsetting 250k drop in inactivity owing to more flexible working, these effects still amount to a 2.1ppt hit to the UK workforce (690k workers) – equivalent to the reduction in employment relative to trend.

Figure 2.26. UK: change in inactivity by reason, 2020–22

Note: Numbers are given relative to January 2020.

Source: ONS and Citi.

Superficially, the prognosis here is not good. The concentration of older workers in particular would ordinarily suggest a slower rate of return to the workforce, and a more persistent subsequent labour supply challenge (Office for National Statistics, 2022e). Two further developments compound the risk:

· Growing numbers suffering long-term sickness. This trend precedes the pandemic, with the number suffering from long-term sickness increasing from around 6 million in 2017 to 7 million today – 17% of the workforce. The participation rate amongst this group, while increasing between 2014 and 2018, has also since begun to stall (Haskel and Martin, 2022). In total, increases amongst this group now amount to half the total increase in inactivity, with students the next-largest contributor.

· A significant increase in house prices. This rise has been the main factor in the aggregate net increase in household wealth. Ordinarily, one would expect this to have a larger marginal effect among older workers who are closer to retirement. Indeed, Disney and Gathergood (2016) note that a local 10% jump in house prices can drive a reduction in participation among older men of around 4%.

The first issue is the main concern. House prices, and changes in nominal household wealth, seem unlikely to weigh on a persistent basis.37

Long-term sickness, by contrast, may well prove a trickier issue. While flows from inactivity to activity amongst this group narrowed somewhat in the mid 2010s, the gap here has increased since – indeed to record levels in recent quarters. This suggests higher levels of inactivity amongst this group seem likely to prove persistent.

On the one hand, reduced COVID incidence and a gradual recovery in the health service should, we think, mean the net increase in inactivity associated with longer-term illness should fall back to around 200–250k above its pre-COVID level. One notable change in recent years has been a reduction in the average age of those reporting long-term sickness, with a particular increase in the density of those suffering under the age of 35 (Haskel and Martin, 2022). We think this suggests more hope for a recovery in the medium term as NHS waiting times come down. However, further setbacks could yet drive these data higher still.

While this issue is rightly the focus of extensive policy discussion, we would note that it accounts still for only half of the overall increase in inactivity since the start of the pandemic. Instead, as Boileau and Cribb (2022) have noted, many of these more recent reductions reflect economic rather than health decisions. Here we think the picture may prove more positive, at least from a labour supply point of view.

And elsewhere the picture seems more positive.

First, reductions in COVID cases have driven a marked reduction in the number temporarily off work with COVID. In Q4 of 2021, as many as 376k workers – 1.5% of the UK workforce – were either sick or self-isolating at any one time owing to the pandemic. Reduced rates here should also weigh on fears amongst older groups. Of those over the age of 50 who have exited the workforce since the start of the pandemic, COVID was still identified by 15% as a reason why they have not returned to work as late as March (Office for National Statistics, 2022e). This can help to explain the bounce in participation amongst the over-65s in recent months.

Second, the reversal of the IR35 (off-payroll working) reforms of 2017 and 2022 will likely drive a notable improvement in participation among the previously self-employed. This had been a key area of growth for the UK labour market since the GFC, in part because of its lower effective tax rate. Since the beginning of the last fiscal year, that changed with the IR35 tax reform. Reduced take-home pay disincentivises work (a ‘substitution effect’). In a range of high-profile sectors – including HGV drivers – these tax changes seem to have been instrumental in shortages (Zangana, 2021). Previously we thought these effects could have meant a net loss of 250k in participation. While it is unlikely all of these will return, these effects should now be less severe.

Third, high inflation in the months ahead is also likely to push more back into the labour market. The impact here hinges on what exactly is driving prices higher. When driven by discretionary components of the consumption basket, higher inflation can weigh on the incentive to work – similar to the increase in taxation. However, as we discuss in Section 2.4, price rises are currently being driven by necessities such as energy and food. In this case, an increase in the price level is better thought of as a reduction in income (Nabarro, 2022a). This increases the incentive to work.

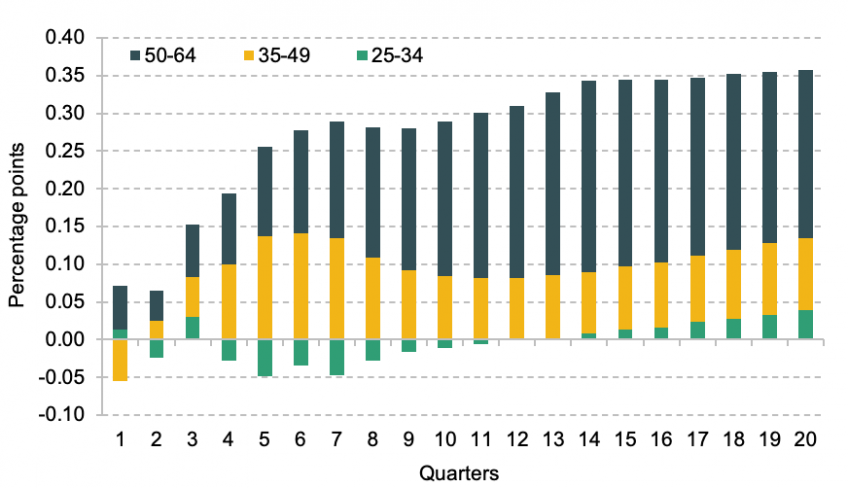

We therefore expect the recent surge in non-core costs to add to labour supply. Generally, given energy and food tend to be larger shares of the budgets of not only poorer but older households, the effect may be especially large. For these households, there are unfortunately few alternatives but to work in order to plug the gap in non-discretionary consumption. For the same reason, monetary tightening tends to have the largest positive impact on labour supply amongst mortgaged and lower-income households (see Bunn et al. (2021) and Cantore et al. (2022) respectively). The asymmetric distribution of household savings suggests these effects should remain relatively large. Historically, the effect associated with non-core inflation has also been focused amongst older age groups (see Figure 2.27).

Figure 2.27. UK: impact of non-core inflation shock on headline participation rates by age

Note: Product of Citi's BVAR participation model. Shock reflects a five-standard-deviation shock to non-core inflation, roughly equivalent to that the UK faces over the next 12 months.

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

How large could this effect be? There are two channels to consider here. The first is participation itself, where we estimate a 4ppt surge in non-core (food and energy) inflation is usually sufficient to push the headline participation rate up by around 0.1ppt all else equal. We currently expect annual non-core inflation here to accelerate to just under 25% over the coming twelve months, enough to add 0.4–0.5ppt to the headline participation rate. As important is the effect of such inflation on net desired hours. When inflation is driven by discretionary spending inflation, these tend to fall. But when driven by energy and food, the effect is large and positive. Alongside the impact of higher participation rates, this could further ameliorate the impact. Across recent survey data, working longer hours is one of the most common responses to the current cost of living shock – with 23% of households citing this as one of their top three actions (Bank of England, 2022b).

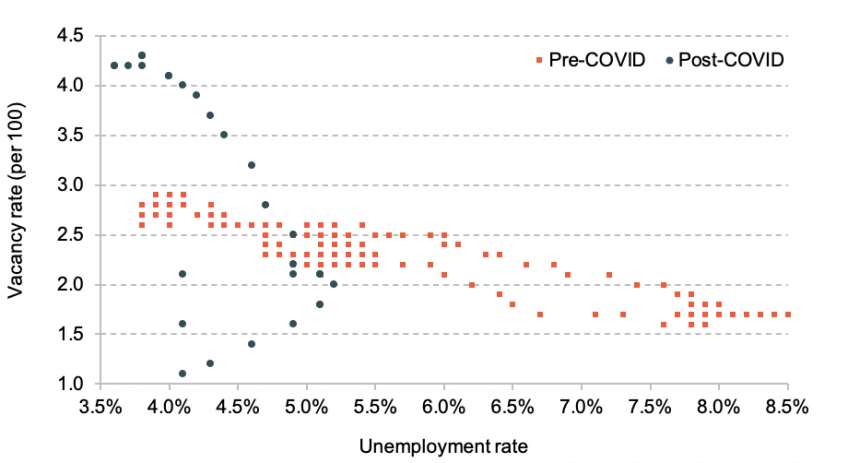

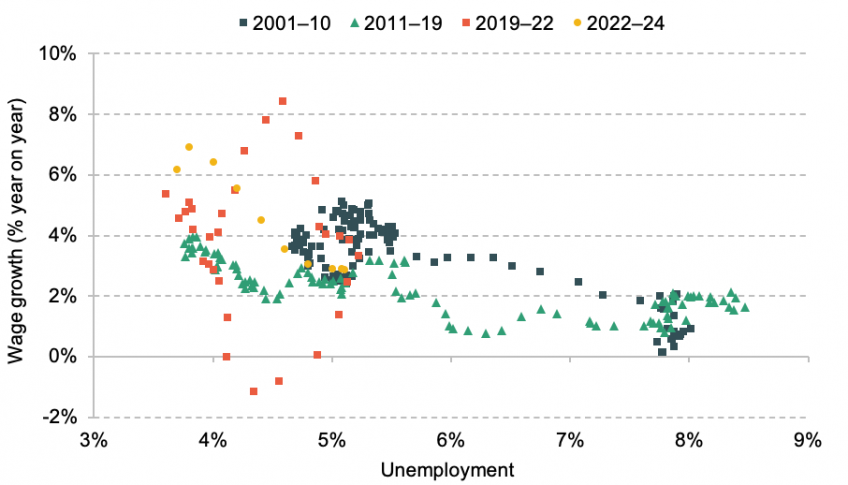

The outlook for unemployment

What might this mean for slack? The starting point here is unambiguously tight. Unemployment fell to 3.6% in the three months to July, the lowest rate since 1974. Short-term unemployment has fallen by 161k compared with pre-pandemic levels, meaning that the average duration of unemployment is now roughly 0.9 months above that in the period immediately before the pandemic began. Headline unemployment therefore likely overstates the degree of slack. Other measures, such as marginal attachment and net additional desired hours, have also fallen to record lows. The net number of workers wanting fewer hours (for less pay) in their current jobs is at its second-highest level since 2004 – at least before some of the effects above have had a chance to materialise. Perhaps most notable, and emphasised by the Monetary Policy Committee, the unemployment to vacancy ratio has also fallen to record lows – suggesting an especially severe mismatch between the strength of labour demand, and spare capacity.

Figure 2.28. UK: Beveridge curve

Source: ONS and Citi Research.

We expect the labour market to now begin to soften, albeit gradually. While the Beveridge curve – the relationship between vacancies and unemployment – appears to have shifted outwards (Figure 2.28), we think the scale of this effect is likely to fade over time.

The point of departure here is that labour markets are always to some degree dysfunctional. Significant heterogeneity means there are always some searching for the right job, and others searching for the right employee – giving rise to frictional unemployment. These effects also mean that should a large backlog of hiring accumulate, this will not be immediately cleared.

The legacy impact of furlough through 2021 has, we think, resulted in just such a backlog. The UK is somewhat unique in cross-national comparison. Rates of job churn are relatively high – around 15% versus 18% in the US and 8.2% in the European Union.38

However, the policy response to the pandemic favoured protecting existing employment relationships. The implication, especially when extending the scheme in 2021, was the accumulation of a very large backlog of hiring. Alongside the drop in participation, this helps explain why the supply side of the UK labour market appears quite so tight, even as GDP is so weak.

These effects are hard to differentiate from more conventional labour market tightness.

The reason why we think these ‘backlog’ effects may be playing at least some role is that, looking across sectors, levels of pre-COVID ‘churn’ tend to be a much stronger indicator of growing tightness than the change in aggregate demand (Nabarro, 2022a). If the current shock was being driven primarily by a conventional excess of supply versus demand, one would expect the largest increase in tightness to be observed within those sectors with the strongest net growth. However, this does not seem to be the case. Instead those sectors with the largest increase in their vacancy to unemployment ratio (versus 2019Q4) include both those with very strong demand – such as professional services – and others where demand is weak – such as hospitality. While it is not the sole driver we think, some of these effects reflect the hiring backlog associated with the pandemic.

Of course, this is not to say the UK labour market is not currently tight. These effects are in essence a further adverse labour supply disruption. But this logic does suggest that some of the current tightness will take some time to abate.

In the interim, three further factors are likely instrumental in determining the speed at which the labour market loosens.

First is the rate at which weak aggregate demand feeds into labour demand. Traditionally vacancies have tended to follow growth with around a three-month lag. It has been a similar story through 2022, with growth peaking in January and vacancies in April. In the months since, much of the soft data have also pointed to a softening demand outlook. In recent months the KPMG–REC survey, for example, has pointed to marked reductions in both hiring and open adverts. Net hiring is now below its long-term average, though outstanding vacancies are a little above. In the months ahead we think the acute margin squeeze we noted in Section 2.2 will weigh on labour demand as well as investment.

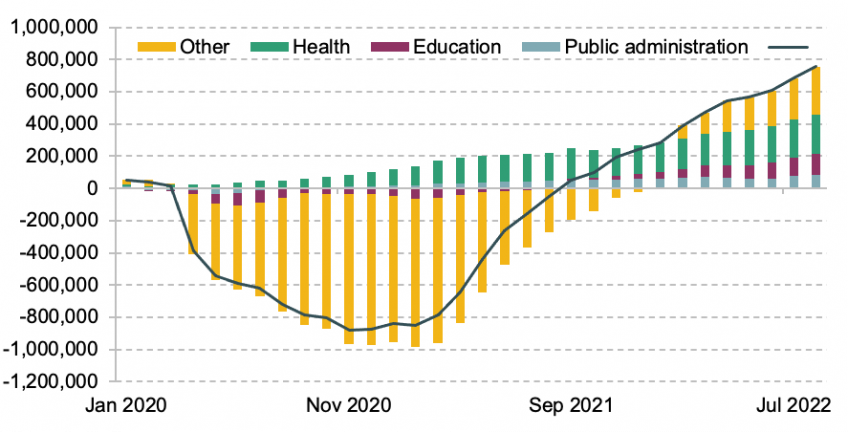

Vacancies may be sticky on the way down. Acute skill shortages are evident in several sectors. High vacancies and poorer matching are likely to prove a little more structural. In some cases the shift towards online job advertising should also mean the cost of advertising is structurally lower, adding to the number of adverts. Both could mean higher rates of ‘fishing’ whereby firms keep vacancies open in the hope of finding the right skills (Saunders, 2017).