Summary

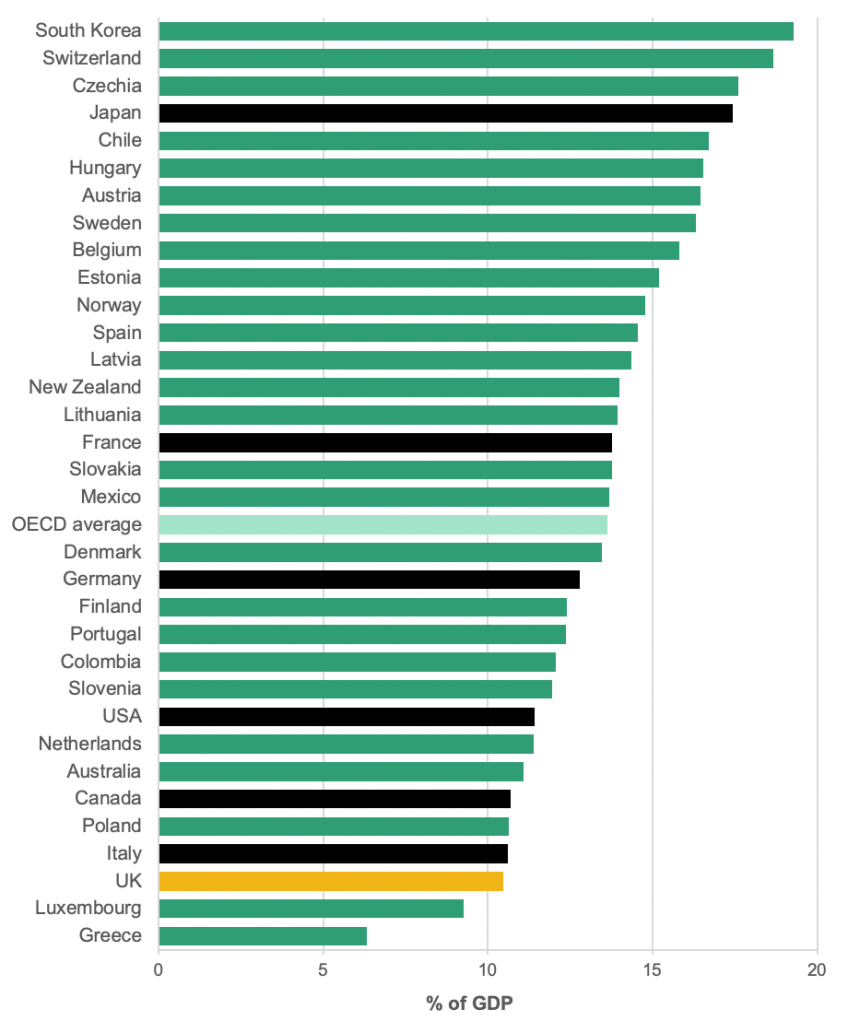

UK business investment is the lowest in the G7 and among the lowest in the developed world.

Tax has a role to play in shaping investment incentives, and the UK’s corporate tax system is one of extremes. While the rate of corporation tax (19%) is exceptionally low, UK investment allowances are amongst the developed world’s least generous. As a result, effective tax rates in the UK (a measure which accounts for the generosity of allowances as well as the headline rate) are middling by international standards. But they vary hugely across different kinds of investment, favouring investment in some assets over others and encouraging borrowing to finance investment.

In this chapter we look closely at the nature of these distortions. We consider how the large package of corporate tax reductions announced in the recent ‘mini-Budget’ is likely to shape incentives to invest and what balance it strikes between encouraging domestic investment and attracting profitable ventures from overseas.

Finally, we consider the road ahead. We examine the likely impact of rising inflation and interest rates. We emphasise the importance of stability and of setting out a clear long-term plan. And we set out a case for genuine structural reform of corporation tax, which could address distortions to the allocation and financing of investment as well as its level.

This chapter was finalised in the wake of the ‘mini-Budget’ delivered to the House of Commons by Kwasi Kwarteng on 23 September 2022. Since then, the main corporation tax announcement in the mini-Budget has been reversed and both Chancellor Kwarteng and Prime Minister Truss have resigned. These developments came too late to be integrated into the chapter before publication. A brief postscript (Section 6.8) acknowledges their implications.

Figure 1. Corporate investment in OECD countries, 2019

Note: Ireland excluded due to the large volatility of its investment statistics. OECD average is the unweighted average of OECD countries for which data are available (excluding Ireland). G7 countries shaded black.

Source: OECD, National accounts of OECD countries: corporate investment, https://doi.org/10.1787/abd72f11-en

Key findings

1. UK rates of corporate investment are among the lowest in the developed world. In 2019 the UK had the lowest level of business investment in the G7 and the third-lowest in the OECD: 10.5% of GDP compared with an OECD average of 13.6%.

2. The UK’s approach to taxing corporate investment is one of extremes. The UK’s headline corporation tax rate (19%) is one of the lowest of any advanced economy. At the same time, however, UK investment allowances are some of the least generous in the OECD. As a result, effective tax rates in the UK (a measure that accounts for both the tax rate and the generosity of allowances) are middling by international standards.

3. Just as importantly, effective tax rates vary drastically between investments. Investing in some assets is penalised much more than investing in others. Meanwhile, investments financed by borrowing can receive substantial subsidies, encouraging firms to take on more debt and to invest in low-return projects that would otherwise be unviable.

4. As inflation rises, these distortions are exacerbated, increasing the premium on achieving genuine structural reform that rationalises the system and reduces such distortions.

5. Kwasi Kwarteng’s dramatic September ‘mini-Budget’ announced the cancellation of a previously planned increase in the rate of corporation tax from 19% to 25%, a decision HM Treasury said would cost a substantial £15 billion a year in forgone revenue (in 2022–23 terms). Alongside this came a (more fiscally modest) increase in the permanent level of the annual investment allowance (AIA), from £200,000 to £1 million, allowing firms to deduct more of their investment spending from taxable profits immediately.

6. Cutting the rate of corporation tax will reduce all of the distortions associated with the tax. However, the tax reduction would be largest for more profitable investments: it would be less effective at reducing the tax on the borderline investments that are most likely to be discouraged by tax. While reducing the rate reduces the distortions to the level, allocation and financing of investment, unless it is reduced to zero, it cannot fully eliminate those distortions.

7. Increasing the AIA, meanwhile, is more cost-effective as a way to encourage investment domestically – it eliminates the disincentive for equity-financed investment in qualifying assets – though not necessarily as a way to increase the UK’s international competitiveness. It also increases subsidies for low-return investments funded by debt – investments that come at a cost to the exchequer but do little for growth.

8. There is strong evidence that, all else being equal, such cuts to corporation tax would be expected to increase investment in the UK. But they will do so only if they are expected to last. Investment decisions are long-term by their nature and the current political environment – and a long history of policy instability – will probably make it harder for the Chancellor to increase investment through the tax system (at least in the short term).

9. While tax matters for investment, it is not all that matters. If interest rates are pushed upwards, or if the UK is seen as providing an unstable environment in which to do business, that could easily outweigh any beneficial effects of lower corporation tax. In other words, corporation tax changes need to be situated within a sensible and credible fiscal framework and broader policy environment if they are to be effective in boosting investment.

10. Only genuine structural reform of how investment is treated by the tax system – as opposed to tweaking individual features – can eliminate distortions to the level, allocation and financing of investment. There is more than one way to achieve this, but it must involve reforming the treatment of debt and equity finance as well as headline tax rates and capital allowances.

11. What is needed is a coherent plan for the future of corporation tax as part of a wider fiscal strategy, clearly communicated, that companies and investors can use as a credible guide to what to expect in the future. There are certainly improvements that could be made. Short of that, some stability would be nice.