The more doctors and nurses employed in the NHS, the more operations, appointments and diagnostic tests it can deliver. This has been a focus of recent policy – including the 2019 Conservative manifesto pledge to increase the number of NHS nurses by 50,000 by 2024 –and the importance of staffing numbers has only intensified in the wake of the pandemic and the subsequent backlog in elective care.

One way to ensure the appropriate numbers of NHS staff members are available, alongside the recruitment of new staff, is to improve the retention of current staff. But despite the importance of retention within the NHS, there is still much that is not known about what drives the leaving decisions of individual staff members. Staff may choose to leave the NHS for many reasons, including – but not limited to – retirement, ill health, unhappiness with working conditions, better outside options, and a lack of progression. Each of these reasons is driven by a mix of different factors and could in turn suggest different policy solutions to improve retention. Given this, what can we say about who is most likely to leave the NHS at any given point in time?

In a new IFS report, published today and funded by the NIHR’s Health and Social Care Workforce Policy Research Unit, we examine some of the factors associated with NHS staff leaving the NHS acute sector. We use the Electronic Staff Record, the monthly payroll of directly employed NHS staff, to analyse the leaving rates of consultants, nurses and midwives, and health-care assistants (HCAs) between 2012 and 2021. Over this period, the leaving rates for these staff groups differed considerably: on average, 0.4% of consultants left the acute sector each month, compared to 0.8% of nurses and midwives and 1.2% of HCAs. Different factors are likely to be related to the leaving decisions of each group, and so we separately consider how different factors are related to exits among each staff group.

We consider associations between leaving and three different categories of factors: the characteristics of individual staff members, the local economic conditions and the characteristics of NHS trusts. This allows us to consider how the leaving rates of each staff group vary by these characteristics when holding all other factors constant.

In this observation, we focus on the findings relating to the characteristics of individual staff members – rather than characteristics of the local area or the trust they work for. This allows us to examine the characteristics of the staff members who are most likely to leave the NHS acute sector in a given month. Importantly, this does not imply that these relationships are causal: for example, other factors (that we do not observe) may be driving these associations. However, knowing which groups have higher rates of leaving can help national policymakers and trusts decide which groups to target with interventions to try to improve retention.

How do leaving rates vary with age and tenure?

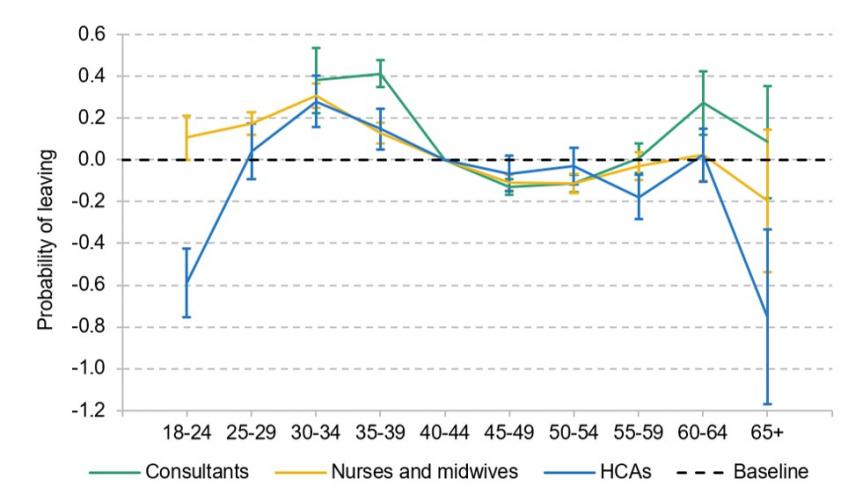

We find that differences in leaving rates between men and women in the same staff group are larger than the differences between those in different job roles of the same gender. Figure 1 shows that for female staff in all three staff groups, the probability of leaving the acute sector peaked in their 30s. This is likely, at least in part, driven by maternity behaviour. Our analysis does not define those on paid maternity leave as leaving, but does include those taking unpaid maternity leave or those who leave before or after having children. Combined with the patterns of part-time working that are common following maternity leave, this shows that over the next decade the NHS can expect to lose significant working time from women currently working in their late 20s.

Figure 1. Probability of leaving the acute sector each month by age, female staff

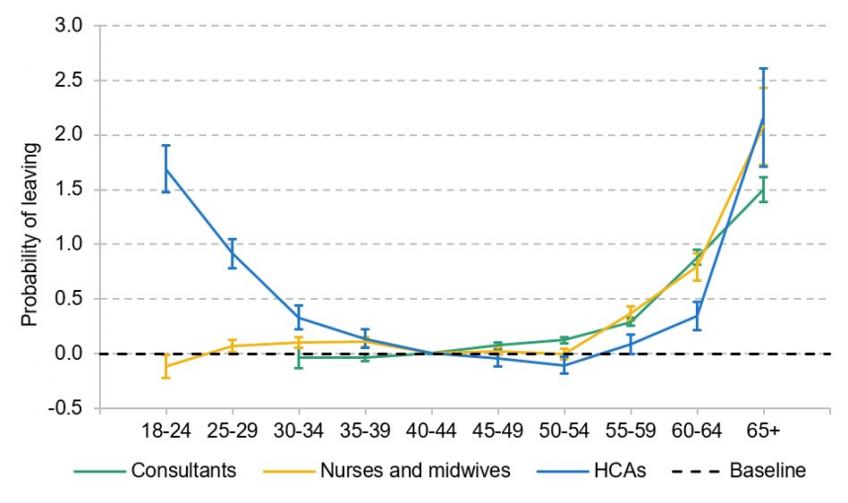

In Figure 2, we see a very different pattern for men. Male consultants and nurses and midwives had almost the same leaving rate up to the age of 55, before rising substantially for those over 55. Male HCAs, unlike their female counterparts, also had very high leaving rates in their 20s.

Alongside age, we also consider the role of tenure at the current trust. For all three staff groups, those with the shortest tenure (0–2 years) had the highest probability of leaving the acute sector. For example, an HCA with tenure of 0–2 years was 62% more likely to leave the acute sector than an HCA with tenure of 5–10 years. Higher tenure was then associated with an increasingly lower probability of leaving until staff had over 25 years of tenure, when the probability of leaving started to rise with increased tenure.

Figure 2. Probability of leaving the acute sector each month by age, male staff

Differences by nationality

There were large differences in leaving rates by nationality, holding all other factors, including age, gender and tenure, constant. Nationality is self-reported in the data, and can change over time (for example, if staff who previously did not have a British nationality gain this nationality after living in the UK for a long time). For consultants, non-British consultants were substantially more likely to leave the acute sector than their British counterparts. These differences are large: in a given month, an EU consultant was 56% more likely to leave the acute sector and a non-EU consultant was 23% more likely. For HCAs, we see the opposite pattern: non-British HCAs were less likely to leave the acute sector in a given month than their British counterparts. HCAs from the EU were 11% less likely to leave the acute sector, while non-EU HCAs were 17% less likely to leave.

For nurses and midwives, the pattern is more complicated. EU staff were 43% more likely to leave than their British counterparts, while non-EU nurses and midwives were 28% less likely to leave.

One potential explanation for these differences could be the impacts of the UK’s exit from the EU. We do, however, find similar patterns between nationality groups even if we only consider data from prior to the 2016 referendum, suggesting that these differences are, at least in part, driven by other factors. But Brexit is likely to have exacerbated these differences: the gap between the probability of an EU nurse or midwife leaving relative to their British counterparts was 68% higher in 2016–21 than in 2012–15, holding all other factors constant. In addition, Brexit has led to nurses and midwives who are recruited from overseas being increasingly recruited from non-EU countries rather than EU countries. Given the historic differences in retention rates that we find, this change in employment mix could help to boost NHS retention rates going forwards.

The role of sickness absences

To examine the relationship between sickness absence and leaving the sector, we split sickness absences into those for physical health reasons and those for mental health reasons. These data were not available to repeat the analysis for HCAs. We find that previous sickness absences are strongly correlated with future exits from the NHS acute sector for both consultants and nurses and midwives.

For consultants, missing 10% of a month of work because of physical sickness was associated with a 30% higher probability of leaving three months later. For nurses and midwives, missing 10% of the month was associated with a 13% increase in the probability of leaving three months later. The associations with mental health absences are even greater in magnitude. For consultants, missing 10% of the month because of mental health issues was associated with a 58% increase in the probability of leaving the NHS three months later, and for nurses and midwives it was associated with a 27% increase.

These results suggest that even relatively small periods of absences are associated with much higher leaving rates for both consultants and nurses and midwives, particularly for absences related to mental health. This could be because those with poor health are more likely both to have sickness absences and to leave the NHS, or because taking sickness absence could be part of the process of leaving the NHS for other reasons.

What other factors are associated with retention?

We have provided a summary of the relationships between leaving decisions and the characteristics of individual staff members. But many other factors will be important determinants of NHS staff job choices. In the report, we also examine the role of local economic conditions and trust characteristics. We find, for example, that regions with higher unemployment rates have lower leaving rates of nurses and midwives and HCAs, and that better reported ‘staff engagement’ for nurses and midwives is associated with lower leaving rates.

But many other factors that matter for retention remain unknown. Indeed, the majority of variation in monthly leaving rates between trusts remains unexplained by our full models of retention: even when including individual characteristics, local economic conditions, trust characteristics, nationwide time trends and persistent differences associated with fixed (and often unobserved) trust attributes, we can only explain up to one-fifth of the variance in trust leaving rates for each staff group. This highlights the difficulties that policymakers face when targeting interventions to improve retention among NHS staff, and the importance of learning more about what drives whether staff decide to stay in or leave the NHS.