In an initial response to the Scottish Government’s budget for next year, David Phillips, an Associate Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies said:

“The Scottish Government has further raised tax rates on high earners relative to the rest of the UK, continuing a trend of higher, more progressive taxes. The revenues raised - estimated at around £95 million, on top of the £8 million from following the UK government’s decision to reduce the threshold at which people start paying the 45p additional rate of income tax - are not to be sniffed at but are small in the context of its budget and cost pressures. The higher tax rates would, for example, cover Scottish NHS spending for only around 48 hours.”

“The main reasons why the funding outlook for the coming year is a little less bad than may have been expected this time last month is the extra funding announced in the UK Government’s Autumn Statement, and an upgrade in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s forecasts for tax revenues relative to the rest of the UK.”

“But funding for public services is still set to be cut overall in real-terms, and by more than in England and Wales. For some services outside the NHS these cuts will be substantial. In the context of obvious pressures on many public services and disputes with public sector workers over pay, these plans may be hard to deliver.”

“The main reason why more services are facing cuts than elsewhere in the UK is that the Scottish Fiscal Commission expects Scotland’s growing range of devolved benefits to eat into a bigger share of its budget. Extra spending on benefits will help tackle child poverty and support more disabled people but will mean less for public services.”

“The way the devolved governments are funded - and particular the Barnett formula - is also delivering smaller percentage increases in funding for Scotland than in England, an issue that we’ll be looking at in more detail in the New Year.”

The Scottish Government’s funding

In its Spending Review published in May, the Scottish Government was assuming its overall funding for day-to-day spending would increase by around 1.7% next year, compared to this. However, all of this and more was expected to be channelled to increased spending on Scotland’s growing range of social security spending, meaning a cut to public service spending of 0.5%. Taking into account the usual measure of inflation used to adjust public spending (which is likely to understate the true cost pressures facing the public sector currently) the funding available for public services was set to fall by 3.5% in real terms. As we highlighted at the time, this would imply renewed austerity for most Scottish public services.

Today’s Budget and Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) shows a slightly less austere picture for the coming year and the year after.

A key reason for this is because of additional funding from the UK government in the Autumn Statement. This amounts to around £1.1 billion in the coming year, compared to the £250 million the Scottish Government had assumed when it set its Spending Review.

However, just as important is an improvement in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s forecasts for Scottish Revenues. Since May (after adjusting for changes to the block grant adjustments subtracted from the Scottish Government's budget) it has revised up forecast net tax receipts by £832 million.

In particular, it’s become much more positive about the outlook for Scottish income tax revenues, not just next year, but over the next four years. Whereas it expected the net effect of devolved income tax to reduce the Scottish Budget by £359 million next year, it now expects it to increase the budget by £325 million. In 2026-27 it expects income tax to generate a net £1.1 billion for the Scottish Budget, compared to a net reduction of £50 million forecast in May. This is a big change to the funding outlook.

Only a small part of this can be explained by the 1 percentage point increases to the top two rates of Scotland’s devolved income tax (which we discuss in more detail below). Much more important seems to be the fact that Scottish revenues performed relatively better than previously expected in 2020-21 - which the SFC expects to continue into the future. It also takes a more optimistic view of both employment and, from 2024-25 onwards, earnings growth than the OBR has for the UK as a whole. Some of this may be because increased oil and gas prices are likely to benefit the Scottish economy, but hurt the wider UK economy. But to the extent that the SFC is just more optimistic about the overall employment and earnings outlook than the OBR, then this improvement in the net income tax position may prove illusory. If so, that could mean difficult decisions in future as the Scottish Government has to pay money back to the UK government.

The final revision is the amount of funding the Scottish Government is set to receive for social security benefits is higher than previously forecast. But spending is forecast to increase by even more. This will mean more of the Scottish Government’s other funding has to be allocated to pay for social security benefits - offsetting some of the extra funding coming through as a result of extra funding via the Barnett formula and improved net tax position.

Taking this all together, the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s forecasts imply that funding for public services is set to fall by 1.6% in real-terms next year compared to this year. This is still a cut overall and given prioritisation of the NHS will still imply big cuts for many service areas - but it is less bad than we would have expected just 1 month ago.

Delays to publishing the Scottish Budget documentation mean we will look at the outlook for different service areas tomorrow (Friday 16th December).

Public sector pay

In the Scottish Government’s Resource Spending Review, published in May 2022, the explicit objective was to hold the overall (devolved) paybill constant in cash terms. This was to be achieved by reducing the size of the (devolved) workforce back to pre-pandemic levels by 2026-27 (a reduction of around 7.3% over the four years from 2022-23, or 1.9% per year). A reduction in the workforce on this scale was always going to pose challenges, particularly given that it was to be achieved without any compulsory redundancies. But assuming it was achieved, it would have been consistent with annual pay rises of approximately 2% per year.

In the event, pay awards this year have far exceeded that amount. Scottish NHS workers, for example, have been offered an average pay rise of 7.5%. Teachers in Scotland have been offered a pay award of between 5% and 6.85%. Police staff in Scotland have accepted a 5% pay offer. Unless the size of the workforce can be sharply reduced, the pay bill will also be considerably higher than previously assumed. Indeed, today’s Budget confirmed that more than £700 million was reallocated to meet the additional costs of these awards this year.

That will pose major budgetary challenges, in this year and beyond. The Scottish Government’s public sector pay policy was not published alongside the Budget today, as originally planned, and so it remains to be seen how they plan to square this circle.

Scottish devolved taxes

As already mentioned, from next April, the Scottish higher and additional rates of tax will each be increased by 1 percentage point (to 42% and 47% respectively), increasing taxes on the highest-income fifth (585,000) of Scottish income taxpayers. The Scottish Fiscal Commission estimate that the increase to the top rate of income tax will raise almost nothing: while it would raise £32 million per year if taxpayers did not respond, once behavioural responses are accounted for (migration, working less, more tax avoidance), the forecast yield falls by 90% to just £3 million. The Scottish Government also confirmed that it would follow the rest of the UK in freezing income tax thresholds and reducing the threshold for the additional rate of income tax to £125,140.

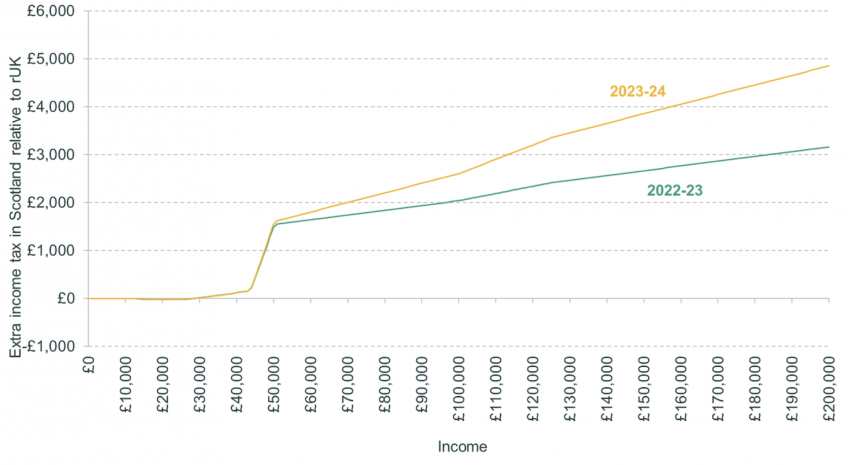

Together these changes further increase the gap in tax rates faced by higher earners in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK, as illustrated in the figure below. A Scottish taxpayer with an income of £30,000 will continue to pay £22 per year more in income tax than a taxpayer in the rest of the UK. A taxpayer on £50,000 will pay £1,552 more (up from £1,489 this year) and a taxpayer on £100,000 will pay £2,606 more (up from £2,043). Those with incomes below £27,800 per year will continue to pay slightly less tax in Scotland than they would in the rest of the UK (typically £22 per year).

Chart 1. Differences in income tax between Scotland and the rest of the UK

Notes: Ignores savings or dividend income.

However, these changes are relatively small beer in the context of the Scottish Government’s budget and the cost pressures it faces. The £95 million from increasing the higher and additional rate of income tax is equivalent to what is spent on the Scottish NHS in 48 hours, for example. Raising significant sums from Scotland’s devolved income tax powers would require a willingness to increase the rates faced by middle and potentially lower earners.

Apart from income tax, the Scottish Government announced an increase in the additional rate of Land and Buildings Transactions Tax (LBTT) levied on second homes and buy-to-let properties to 6%. This comes on top of standard rates of LBTT, and mean that a second or buy-to-let property purchased for £250,000 faces a tax bill of £17,100 (6.8%), compared to £2,100 for an owner-occupied property, and £7,500 for a buy-to-let property in the rest of the UK.

LBTT is one of the most damaging taxes - preventing mutually beneficial transactions, and reducing geographic mobility. It should be reduced and preferably abolished, and so it is disappointing to see further increases in this tax, which in this case will further penalise the rental sector relative to the owner-occupied sector.

The business rates tax rate (the multiplier) will also be frozen at a cost of just over £300 million. In the short-term this is likely to benefit occupiers, but in the longer-run, it will likely lead to higher rents, with most of the benefits accruing to landlords.

Unlike England and Wales though, there is to be no specific relief for the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors. If continued for the long-term, such relief would also likely end up benefiting landlords more than occupiers. But the main beneficiaries in the short term likely would have been small businesses in these sectors.