The late publication of the Scottish Budget documentation yesterday meant that we were unable to analyse the plans for different public service budgets. We look at this in this follow-up piece.

Please note that this comment has been updated following the identification of an error in our previous calculations of the cost of additional pay for local government workers. Originally we were including the funding line ‘cost of living award’ in the local government section of the Autumn Budget revision. However, this relates to the council tax rebates provided to Scottish residents, rather than cost of living pay awards. The correct figure for the additional funding for pay in 2022-23 is £260 million not the £540 million previously reported. This also means the adjusted 5% cut for the main local government portfolio previously reported overstates the true real-terms cut, but it remains the case that the Budget documentation understates it.

All other figures in the report are unchanged, including the overall top-up to funding in 2022-23 that is not accounted for in the Budget.

Bee Boileau, a research economist at the IFS said:

“More funding from the UK government and a better showing from Scotland’s devolved taxes means that funding for most services next year has been topped up compared to plans set out in the Scottish Spending Review in May.

The Scottish Budget suggests that funding for health and social care will now grow by 2.9% in real terms between 2022–23 and 2023–24, compared to the 0.2% real-terms growth planned in May, that the budget for justice, policing and veterans will grow by 2.5% in real terms, compared to the 2.4% cut set out in May, and that cuts to local government budgets will be only 0.2%, compared to the 2.4% cut previously planned.

But these figures overstate the funding increase from this year to next for many services. That is because the Scottish Budget compares plans for next year with what was originally budgeted to be spent this year, and in many cases budgets for this year have since been topped up. Local government is a notable case in point, where a sizeable £260 million extra has been found for pay awards this year: the costs of these awards will continue into next year, but this funding has been excluded from the year-to-year comparisons quoted by the Scottish Government. Taking this into account suggests that rather than falling by 0.2% in real terms, as suggested by the Scottish Budget, funding for the main local government portfolio will in fact fall by substantially more.

In all, around £1.3 billion of in-year top-ups to funding this year have been excluded from the figures. This means that rather than increasing by an average of 1.9%, as reported in the Budget, Scottish Fiscal Commission figures imply real-terms spending on devolved public services will be 1.6% lower next year compared to this year.”

Analysis of plans for public service spending

Yesterday’s announcements

Yesterday’s Scottish Budget suggests that devolved public service spending will increase by 1.9% in real terms between 2022–23 and 2023–24. This is a significant improvement compared to the May Spending Review, when the Scottish Government said that spending was set to fall by 1.0% in real terms.

This improvement is largely a result of additional funding from the UK government for the next two years in last month’s Autumn Statement, as well as upgrades in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s forecasts for Scottish tax revenues relative to the rest of the UK. These two factors more than offset the increase in inflation forecast for next year since May’s Scottish Spending Review.

These boosts to funding mean that compared to the plans for 2023–24 set out in May, additional funding has been found for a range of services. For example, the Scottish Government’s Budget documentation suggests that:

- The health and social care budget is set to grow by 6.2% in cash-terms between 2022–23 and 2023–24, equivalent to 2.9% in real-terms. This is substantially more generous than the 0.2% real-terms increase set out in May’s Spending Review.

- The local government budget is now set to fall only by 0.2% in real terms between 2022–23 and 2023–24, whereas it was set to fall by 2.4% in the Spending Review.

- The police budget is set to rise by 1.8% in real terms, whereas in the Spending Review it was set to fall by 2.4% in real terms.

- The higher education budget is set to fall by 0.7% in real terms, whereas in May it was set to fall by 2.4% in real terms.

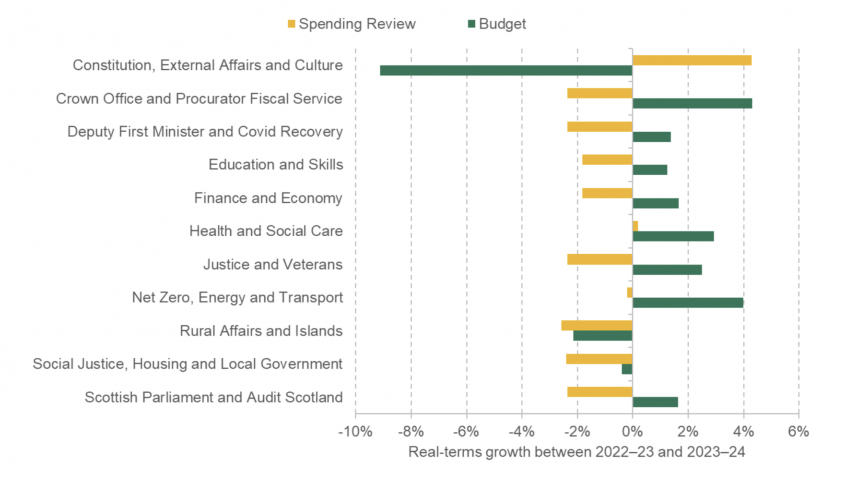

Almost across the board, funding changes look more generous in the Budget compared to the Spending Review, although there are exceptions. In particular, real-terms funding for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture department is set to fall 9.1% in real terms, whereas in May it was planned to grow by 4.3%. This reflects the re-allocation of funding no longer being set aside for an independence referendum next year.

Chart 1. Real-terms change in funding between 2022–23 and 2023–24, as set out in the May Spending Review and the December Budget, by department

Note: Comparisons are based on original budgets for 2022–23 and therefore overstate increases compared to updated budget. The real-terms change reflects both the changes to nominal funding and the change in the GDP deflator between May and November. Social Justice, Housing, and Local Government budget excludes social security assistance.

Source: Authors’ calculations using GDP deflators from May 2022 and November 2022, Resource Spending Review May 2022, Scottish Budget 2023–24

The true funding increase next year compared to this year will be smaller than set out in the Budget.

However, two important considerations mean that these figures overstate the true increase in resources next year compared to this – and understate the difficulties many Scottish public services will face.

First, the measure of inflation typically used to adjust public spending for inflation, and which is used in the Scottish Budget, the GDP deflator, is likely to be underestimating the real cost pressures currently facing public services. As a measure of domestic inflation, it excludes rises in the price of imports – including much of our energy and food, for which prices are rising particularly rapidly. As a result, while the GDP deflator is forecast to increase by 4.9% in 2022–23, and 3.2% in 2023–24, consumer price inflation (CPI) is forecast to average 10% this financial year and 5.5% in 2023–24 according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Imported energy and food make up a much smaller share of government spending than household spending, so CPI would likely overstate the rate of inflation facing public services. However, high CPI inflation is currently exerting significant pressure on public sector pay, which makes up a large proportion of resource spending. In Scotland, partially in response to elevated CPI inflation, more generous public sector pay awards have been offered than in the rest of the UK, increasing pressure on this year’s budgets. Rises in energy prices since March and further increases in pay next year therefore mean it’s likely that the true rate of inflation facing public services this year and next will lie between the GDP deflator and CPI.

Second, the figures reported in yesterday’s Budget overstate the cash terms increase in funding next year compared to this. This is because they compare spending next year to what was originally planned to be spent this year. However, for various reasons, including more funding from the UK government, and the Scottish government making more drawdowns from reserves than anticipated, Scottish Fiscal Commission figures imply that spending on public services this year will be around £1.3 billion higher than originally planned.

This higher baseline makes a large difference to real-terms growth estimates: while the Scottish Budget document implies that real-terms resource spending would be on course to increase by 1.9% in real terms between 2022–23 and 2023–24, the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s figures, with the higher baseline, imply that real-terms spending will instead be set to fall by 1.6%.

Much of the additional spending already announced in 2022–23 has gone to local government, including around £260 million for higher than expected pay awards. Taking this boost to funding in 2022–23 into account, local government funding would actually be set to fall by much more than the 0.2% reported in the Scottish budget.

Similar, although smaller, in-year increases to spending in 2022–23 for a number of other services mean that the true change in funding for them next year will also be less generous than set out in the Scottish Government Budget.

Comparisons with England

Making accurate comparisons to changes to departmental budgets in England over this period is difficult. Scottish government departments are structured differently from departments in England, meaning that in many cases there are no obvious equivalents with which Scottish changes can be compared. There is also the problem that the Scottish figures ignore in-year top-ups as previously discussed. But rough comparisons in some areas can be made.

The fall in real-terms local government spending in Scotland, especially when funding for pay awards this year is taken into account, is notable when compared to what has happened to English schools and local government budgets. Between 2022–23 and 2023–24, the English schools budget is set to increase by 3.2% in real-terms, and funding for councils is set to increase significantly too. Scotland’s local government budget (which covers most school spending), in contrast, is set to fall in real terms after accounting for in-year top-ups this year. Increases in council tax will only be able to offset a small part of these differences.

Local government and schools appear to be the big losers relative to England – funding for the NHS, Justice and particularly transport looks set to increase by more in Scotland than England.

Concluding remarks

These different choices on which services to prioritise, alongside changes to tax policy, and the channelling of increasing amounts of funding to social security benefits (reducing the amount available for public services) are devolution in action.

Extra funding from the UK government, an unexpected significant improvement in Scotland’s underlying tax revenue growth, and some modest tax rises have provided a decent boost to funding next year compared to what was previously planned. But by ignoring the in-year boosts to funding provided to many services this year, the Budget document overstates the increases next year. So the outlook for services will be tougher than it looks – especially for local government, which is facing a substantial cut to its funding.