The Scottish Government has today published the latest version of its Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) report, covering the 2022–23 fiscal year. This provides an estimate of the total amount of government revenue raised in Scotland, the total amount of public spending benefiting Scotland (which includes both spending specifically for/in Scotland, as well as a share of spending on things such as debt interest, defence and foreign aid that are deemed to benefit the whole of the UK broadly equally on a per capita basis), and the gap between these two figures. This gap is Scotland’s net fiscal balance – and is, in effect, an estimate of the amount of borrowing the UK government is undertaking on behalf of Scotland as opposed to the rest of the UK.

Like nearly all economic statistics, GERS is subject to a degree of potential measurement error. The figures it contains are also backward- rather than forward-looking, and so do not, on their own, reflect how revenues and spending may evolve in future, or the different choices different governments could take. However, their status as National Statistics means they have been independently assessed as being based on sound methods and being produced free from political interference. And they are widely recognised as a sensible starting point for assessing the kind of fiscal challenges and opportunities that an independent Scotland would initially face – for example, by the Fraser of Allander Institute and the SNP’s Sustainable Growth Commission of 2016–18.

So, what do today’s figures show?

A smaller but still big deficit

2022–23 saw the fiscal position of the UK as a whole deteriorate as the cost of energy bills support and surging debt interest payments pushed up government spending. As a result of this, UK government borrowing increased from £122 billion in 2021–22 to £132 billion in 2022–23 – meaning it remained at 5.2% of GDP.

In contrast, GERS shows that Scotland’s fiscal position improved in 2022–23. This is because the surge in oil and especially gas prices that pushed up energy costs also boosted tax revenues from oil and gas production in the North Sea, as did higher tax rates on these profits, and GERS estimates that around 89% of these revenues came from activities in Scottish waters. In contrast, Scotland’s share of the extra spending on energy bills support and debt interest was close to its population share (8%).

The bigger boost to revenues in Scotland means its notional fiscal deficit is estimated to have fallen by £5.8 billion to £19.1 billion – or from 12.8% of GDP to 9.0%. This is still substantially higher than the figure for the UK as a whole though, with estimated borrowing per person being around £1,530 higher than the figure for the UK as a whole (£3,485 versus £1,955).

The main factor driving this higher fiscal deficit is much higher public spending: overall government spending in 2022–23 is estimated to have been £2,217 higher for Scotland (£19,459) than for the UK as a whole (£17,243). Most of this difference is due to the much higher levels of funding the Scottish Government receives to pay for devolved public services than is spent on comparable services in England.

Scotland’s higher fiscal deficit also partly reflects lower onshore tax revenues (£14,254 per person versus £15,113 in the UK as a whole). But this is a much smaller factor than in the fiscal deficits of Northern Ireland, Wales, and the Midlands and North of England – as we have previously highlighted.

Offsetting the higher spending and lower onshore revenues is the much higher oil and gas revenues – estimated at £1,713 per person, compared with £158 per person across the UK as a whole. This reflects the fact that, as mentioned above, the vast majority of oil and gas revenues relate to activity off the coast of Scotland.

The future outlook

The future evolution of the fiscal position of both Scotland and the UK as a whole is uncertain and will be affected by both economic factors (including in the case of Scotland in particular, oil and gas prices and production) and policy decisions. Bearing this in mind, we have projected the GERS figures forward using the OBR’s latest fiscal forecasts for the UK as a whole. In doing so, we have assumed Scotland’s onshore tax revenues and government spending per capita move in line with the OBR’s forecasts for the UK as a whole, and that Scotland’s share of oil and gas revenues trends back to 100% by 2027–28 as the contribution of oil and gas to these revenues moves back closer to levels prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Our previous update explains why we think these assumptions are a reasonable baseline scenario.

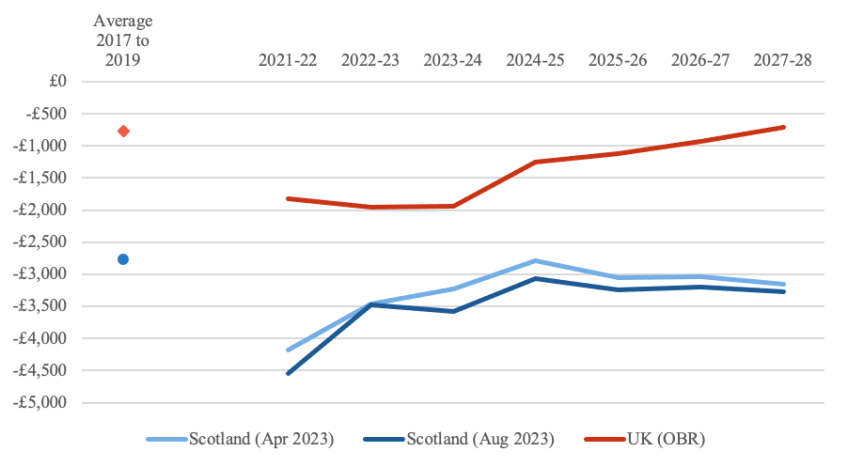

Figure 1 shows the OBR’s March 2023 forecasts for the UK’s fiscal deficit (red), and our latest projections for Scotland (dark blue), expressed in £s per person, for ease of comparability. It also shows our previous (April) projections for Scotland (in light blue).

Let us focus first on the UK figures (the red line). The OBR forecasts that over the next four years, borrowing will fall, as spending on energy bills support ceases and on debt interest falls back, a number of tax-raising measures boost revenues and tough plans for public service spending – which imply cuts to some services – are implemented.

If we instead focus on our latest projection for Scotland (the dark blue line), the picture is rather different. Based on current oil and gas revenue forecasts and if onshore revenue and spending move in line with the rest of the UK, Scotland’s notional fiscal deficit would only fall modestly in cash terms over the next four years, to around £3,340 per person in 2027–28, over £2,500 higher than the figure for the UK as a whole. Measured as a share of GDP, Scotland’s notional fiscal deficit would fall somewhat more (from 9.0% to around 7.5%), but the gap with the rest of the UK would also grow (given the UK’s deficit is forecast to fall from 5.2% of GDP to 1.7%). This reflects the fact that the OBR forecasts a fall in oil and gas revenues to roughly halve (to £5 billion) by 2027–28, although this remains well above the levels seen in the second half of the 2010s.

Figure 1. Projected Scottish and UK fiscal balances, £s per capita, 2021–22 to 2027–28

Source: Author’s calculations using OBR EFO March 2023 and November 2022, GERS 2021–22 and 2022–23, ONS Population Projections and assumptions discussed in text.

Finally, by comparing our latest projections with those made in April (the light blue line), we can see that our projections for 2022–23 were almost spot on. Digging deeper, we can see that we slightly underestimated the improvement in Scotland’s public finances in the most recent year of data (the dark blue line is steeper than the light blue one between 2021–22 and 2022–23), but that was offset by downwards revisions to the figures for 2021–22 in the latest edition of GERS (the dark blue line starts at a lower level in 2021–22). This is a reminder that both the GERS statistics and our economic projections come with some margin of error – but that they still have significant value.

Does this matter?

As part of the UK, Scotland’s notional fiscal deficit is subsumed within the wider UK fiscal deficit. Under independence, that would change.

The Scottish Government’s Medium-Term Financial Strategy (and our analysis of that report and Scotland’s longer-term funding outlook) shows that Scotland faces tricky decisions on tax and spending within the Union. These GERS-based projections remind us that independence would be no panacea for this issue – indeed, Scotland’s larger notional fiscal deficit means that unless economic growth and hence tax revenues were boosted, tax rises or spending cuts would likely need to be even larger in the years ahead.

Scotland has experienced periods where growth in employment, earnings and the economy as a whole has consistently outpaced that of the UK as a whole – during the 2000s, for example, as our recent report highlighted – and could do so again in future, especially if long-standing issues with productivity and skills can be tackled. But Scotland will also face tricky headwinds in the years ahead as declines in the oil and gas sectors hit onshore as well as offshore tax revenues, and more rapid ageing of the population affects tax and spending. Such issues are at the heart of debates about independence not just because they relate directly to people’s jobs and salaries, but also because they have an important bearing on Scotland’s public finances, and hence the taxes people could pay and the services they could expect to enjoy post-independence.