Following the publication of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) November 2022 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we have updated our medium-term projections of Scotland’s underlying public finances. These project forward the outturn figures in the official Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland (GERS) publication, produced by Scottish Government statisticians to National Statistics standards.

At the outset it is important to note that these projections are subject to even more uncertainty than usual. Three particular factors relevant for Scotland are worth highlighting.

First, the share of oil and gas revenues which relate to production in Scotland’s portion of the North Sea. In recent years, with oil and gas revenues low, this has not mattered much for Scotland’s overall fiscal position. But with oil and gas revenues surging it could now make a difference. Over the last ten years, Scotland’s share of revenues has ranged from 60% in 2014–15 to being over 100% in each of the last four years (reflecting negative revenues for England). However, given that the current and forecast increase in gas prices (over 250% between 2021 and 2023) is much larger than for oil prices (up 50% over the same period), and Scotland’s share of UK gas production (61% in 2019) is lower than its share of UK oil production (95% in 2019), we may expect Scotland’s share of revenues to fall back. We therefore consider two scenarios: (a) Scotland’s share of oil and gas revenues is 100% of the UK total between 2022–23 and 2027–28; (b) Scotland’s share of oil and gas revenues falls to 85% in 2022–23 and 80% in 2023–24, before recovering (as gas prices fall relative to oil prices) to 100% by 2027–28.

Second, and related to this, the big increase in oil and gas prices will boost the contribution of oil and gas output to the UK’s GDP. Because most of this output would be in Scottish waters, this would particularly boost Scotland’s GDP. This would act to reduce slightly the size of Scotland’s deficit when measured as a share of GDP. In our main quantitative modelling we therefore focus on comparing cash budget deficits per person, as opposed to as a percentage of GDP.

Third, the share of the revenues from the new tax on electricity generators’ profits that comes from Scotland. In 2020, around 17% of the UK’s electricity was generated in Scotland, including 23% of the electricity generated from sources other than gas. It is the latter figure that will matter most given that companies producing electricity from gas are less likely to be making high profits than those producing electricity from nuclear and renewable sources. For this reason, we assume that a quarter of the revenues from this tax will come from Scotland, but this is very uncertain.

Alongside these assumptions on revenues from oil, gas and electricity producers, our projections assume that Scotland’s onshore tax revenues and government spending per capita move in line with the OBR’s forecasts for the UK as a whole. In reality, trends in Scotland are unlikely to exactly match those of the UK as a whole. On the one hand, increases in activity in the North Sea may boost onshore tax revenues in Scotland by more than in the UK as a whole. But on the other hand, the types of taxes which the OBR forecasts will increase the most over the next five years, such as income tax, onshore corporation tax and council tax, make up a lower share of Scotland’s overall tax take than in the UK as a whole. And over the next 18 months, we may expect Scottish households to benefit more from the Energy Price Guarantee, given colder winters. With different effects working in different directions, assuming that revenues and spending track UK-wide forecasts doesn’t seem an unreasonable baseline scenario.

Our projections for Scotland’s underlying deficit to 2027–28

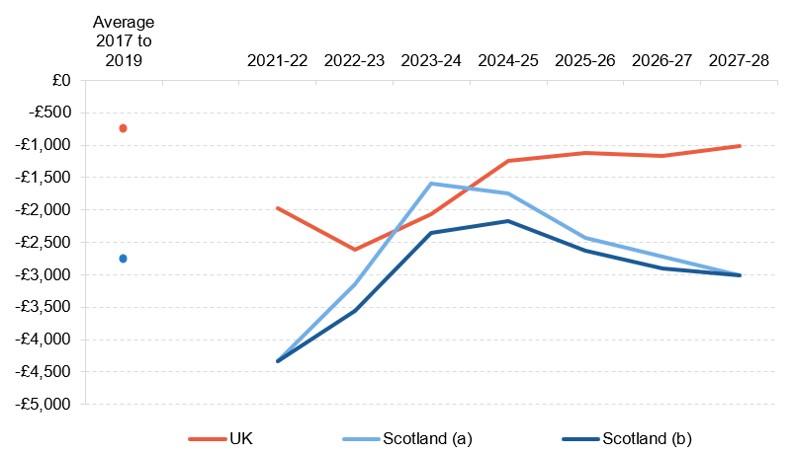

Figure 1 shows our resulting projections for Scotland’s underlying budget deficit under our two scenarios for Scotland’s share of oil and gas revenues, compared to the OBR’s forecasts for the UK as a whole. The light blue line shows our projections for Scotland’s deficit under scenario (a), if 100% of North Sea oil and gas revenues are generated in the Scottish portion of the North Sea. The darker blue line shows our projections under scenario (b), if Scotland’s share of North Sea oil and gas revenues declines to 80% before recovering.

The Figure shows that Scotland’s underlying budget deficit is set to fall substantially between 2021–22 and 2023–24: from the equivalent of just over £4,300 per person, to just under £1,600 under scenario (a) and just over £2,300 under scenario (b). In contrast the UK’s deficit is forecast by the OBR to be equivalent to around £2,000 per person in each of these years (and increase to over £2,600 per person in 2022–23).

Figure 1. Projected Scottish and UK fiscal balances, £s per capita, 2021–22 to 2027–28

Source: Author’s calculations using OBR EFO November 2022, GERS 2021–22, ONS Population Projections and assumptions discussed in text.

The reason for these starkly different trends is a substantial increase in oil and gas revenues, driven by the aforementioned increases in prices and tax rates. The OBR forecasts that taxes on North Sea oil and gas are set to raise almost £15 billion this year and £21 billion next year. With most, and potentially all, of this revenue coming from production in Scottish waters, this would significantly reduce Scotland’s underlying budget deficit, at the same time as the UK’s budget deficit is being increased as a result of the even bigger amounts being spent on the Energy Price Guarantee, and other support with the cost of living. Scotland benefits from these measures too, but spending on them is spread across the entire UK.

Depending on the share of North Sea oil and gas revenues that relate to production in Scottish waters, Scotland’s underlying budget deficit could therefore be similar to or even lower than that of the UK as a whole next year. This is a remarkably rosier picture than would have been expected at the start of this year: our last projections from January 2022, were for Scotland’s underlying deficit in 2023-24 to be £2,000 per person (or 6% of GDP) higher than that of the UK as a whole.

However, the OBR forecasts that despite plans to maintain higher tax rates on oil, gas and electricity producers until 2028, tax revenues will fall back from 2024–25 onwards. This largely reflects the fact that it forecasts oil and gas prices will fall back – although in the case of gas they would still be double their 2021 levels and 3 to 4 times their pre-COVID levels even in 2027–28. But it also reflects a forecast decline in oil and gas production, in line with long-run trends: down around 30% between 2021–22 and 2027–28.

On the basis of a forecast fall in UK oil and gas revenues to £15 billion in 2024–25 and £8 billion in 2027–28, we project Scotland’s budget deficit would increase after 2023–24, despite the economy recovering from recession, spending restraint, and tax rises all leading to the deficit of the UK as a whole falling.

As a result, we project Scotland’s deficit could equate to around £3,000 per person in 2027–28, compared to around £1,000 per person under the OBR’s forecasts for the UK as a whole. This difference of £2,000 per person is equivalent to around 4 – 5% of projected Scottish GDP in that year, and means a total underlying Scottish deficit of just under 7% of GDP (compared to just under 2½% forecast for the UK as a whole).

This is again lower than our projections from the start of the year – when Scotland’s underlying deficit was projected to be around 7.5%, around 6 percentage points higher than the UK-wide figure of 1.5%. This reflects the fact the OBR forecasts that oil and gas revenues will still be substantially higher in the second half of the 2020s than it previously expected, even if well down from the peak expected next year.

Concluding remarks

As highlighted above, these projections are subject to significant uncertainty – stronger or weaker economic performance across the UK or in Scotland specifically, and higher or lower oil and gas revenues, could mean the UK-wide and underlying Scottish budget deficits are significantly higher or lower than set out here. Even if the deficit were a couple of percent of GDP lower than the 7% projected here though, this would be unsustainable on a long-term basis for an independent country. In the absence of faster growth, an independent Scotland would therefore likely need additional tax rises and/or spending cuts on top of those planned by the UK government over the next few years.

The Scottish Government is publishing a series of reports setting out its vision for economic and broader public policy in an independent Scotland – one of the aims of which is to support faster growth. We published an initial response to its main paper on the economy in October, and over the coming months we plan to look in more detail at the plans set out, including their potential effects on the public finances.