The Scottish Government has published updated projections of its funding and the spending that would be needed to maintain service provision for the next five years as part of its Medium-Term Financial Strategy (MTFS). The central funding projections are based on the latest forecasts for revenues from devolved taxes and comparable taxes in the rest of the UK produced by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) and Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), and spending plans set out by the UK government in its March 2023 Budget. The projections for day-to-day (resource) spending assume that:

- Spending on devolved social security benefits grows in line with the SFC’s latest forecasts, which are for spending to grow by 8.7% a year (7.3% a year in real-terms, on average, given OBR forecasts for economy-wide inflation), driven in part by the roll out of new disability benefits which are expected to lead to more successful claimants.

- Spending on health and social care services will need to increase by 4% a year in cash-terms (2.6% a year in real-terms) in order to meet rising demands and costs.

- Spending on all other services will need to increase to cover some increase in staff numbers, 2% increases in pay per year from 2024–25 onwards, and the impact of economy-wide inflation. This equates to an increase of around 2.5% a year in cash terms (or 1% a year in real-terms).

These assumptions lead to a somewhat less dire picture than was presented in the Scottish Government’s last comparable projections, published in December 2021, when a medium-term funding gap of £3.5 billion per year for day-to-day spending was projected. This improvement largely reflects the fact that whereas in December 2021, the SFC was forecasting that Scottish income tax revenues would grow more slowly than the OBR forecast for the rest of the UK, squeezing Scottish Government funding, the SFC is now forecasting slightly faster growth in Scottish income tax revenues. This partly reflects the fact that the SFC now assumes that the Scottish higher rate tax threshold will be frozen (as it will in the rest of the UK) over the next few years. It also partly reflects the fact that the SFC is now forecasting faster earnings growth (3.0% a year on average) than the OBR (2.4% a year on average) from 2023–24 onwards, following a period of slower growth. Alongside previous increases in tax rates on the higher-earning half of Scottish taxpayers, these changes mean that income tax is forecast to contribute a net £1.5 billion to the Scottish Government’s funding by the end of the projections, compared to reducing it by £0.4 billion, as was the case in December 2021.

A looming funding gap…

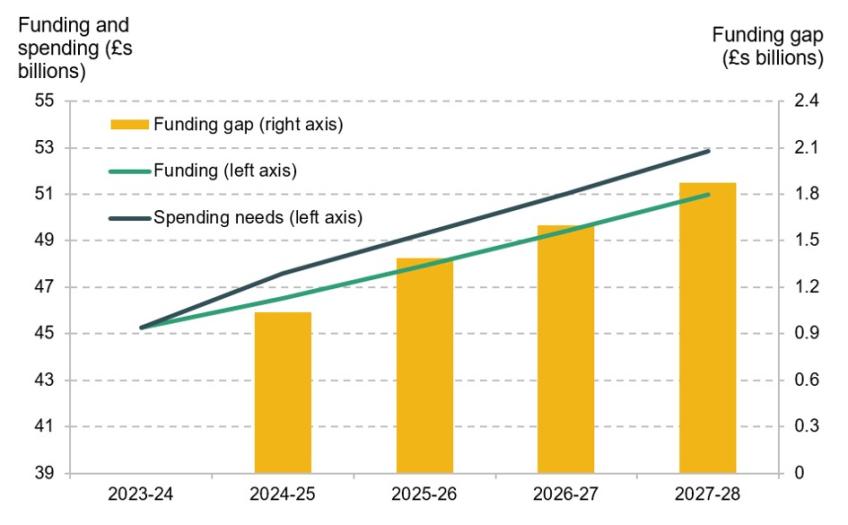

Nevertheless, overall day-to-day spending needs are still projected to grow by more (3.9% a year on average in cash-terms, and 2.6% in real-terms), than available funding (3.0% in cash-terms and 1.6% in real-terms) over the next 4 years. This means that under the Scottish Government’s central projections, spending needs are set to exceed available funding by £1 billion next year (2024–25) and £1.9 billion a year by 2027–28, as illustrated in Figure 1. This is equivalent to around 2% and 3.5% of the Scottish Government’s projected spending needs in these two years, respectively.

Figure 1. MTFS central funding and spending needs projections and resulting ‘funding gap’, 2023–24 to 2027–28

Source: Scottish Government Medium-Term Financial Strategy.

In the absence of additional funding from the UK government, addressing this gap will require the Scottish Government to cut back some areas of public spending or increases in tax revenues. Finding £1.9 billion from increases in income tax alone would require an increase of around 3.5 percentage points to all Scottish income tax rates, or a further 15-20 percentage point increase in the top two income tax rates, that the Scottish Government just recently increased. £1.9 billion is equivalent to over 80% of Scottish Government spending on police and fire services, or over 60% of spending on universities, colleges and student support. It is therefore no small amount of money and addressing a gap of this scale would require tough choices.

… and significant uncertainty

Both the outlook for future funding and spending needs are highly uncertain though. In recognition of this, the Scottish Government sets out a range of scenarios for both, leading to projections that range from a funding gap of up to £3.9 billion to a funding surplus of up to £2.0 billion in 2027–28.

In the absence of additional funding from the UK government though, the central scenario outlined above probably understates the funding pressures the Scottish Government is likely to face over the next few years.

First, the assumed 4% cash-terms and 2.6% real-terms annual increases in health and social care spending needs are, if anything, a little on the low side. The Scottish Government’s budget for the current financial year, 2023–24, increased health spending by 2.9% in real-terms compared to the amount budgeted for in 2022–23, for example. If health spending needs were instead assumed to increase at this rate over the following four years (2.9% rather than 2.6%), the funding gap would grow to £2.1 billion by 2027-28.

Second, the forecast improvements in income tax revenue performance that help bolster the Scottish Government’s (still difficult) funding position are at least partly driven by differences in the overall level of optimism on earnings growth between SFC and the OBR, rather than an expectation that the Scottish economy will outperform that of the rest of the UK. Put simply, the SFC expects earnings growth to be higher across the UK than the OBR does. If the SFC is right, then income tax revenues in the rest of the UK will be higher than the OBR is forecasting. This will lead to the ‘block grant adjustment’ subtracted from the Scottish Government’s UK government funding to account for income tax devolution to be higher than currently assumed, reducing net revenues from Scotland’s devolved income taxes. On the other hand, if the OBR is right about overall trends in earnings, then Scottish income tax revenues will come in lower than forecast by the SFC, again reducing their net contribution to the Scottish budget. If only half the improvement in the Scottish income tax position forecast between 2023–24 and 2027–28 materialises, the funding gap would grow to £2.5 billion by 2027-28.

Third, the Scottish Government is likely to want to increase spending in some areas by more than enough to simply maintain service provision. For example, it remains committed to the roll out of a National Care Service, with better pay, conditions and training for staff – and a price tag last estimated at between £250 million and £500 million a year, even before considering improvements in pay and conditions for private and third-sector social care workers. More recently, UK government plans for a significant expansion of childcare in England are set to generate over £400 million a year for the Scottish Government by 2027–28. While the Scottish Government is under no obligation to use this funding to expand childcare provision, it is likely to come under significant political pressure to do so – not least because the Scottish National Party pledged in its 2021 election manifesto to begin expanding free childcare to 1- and 2-year olds, and offer wrap-around childcare for school-aged children. Funding such expansions in provision would increase the gap between funding available for other services and their spending needs.

However, future UK government spending plans seem more likely to be topped up than cut back, generating additional funding for the Scottish Government via the Barnett Formula. Current plans for overall spending mean that if English NHS spending is increased by 3.8% a year in real-terms (in line with its long-run growth rate), defence spending is increased so that it would reach 2.5% of GDP by 2030, and total school spending is held constant in real-terms, a range of other services could see real-terms cuts of over 3% a year, on average, between 2024–25 and 2027–28. Not least because these other services often bore the brunt of 2010s austerity, such cuts would be very challenging to deliver. The UK government may therefore choose to increase overall spending by more, instead.

What can the Scottish Government do?

In order to generate £1.9 billion of additional funding for the Scottish Government in 2027–28 via the Barnett formula, the UK government would have to increase its spending by around £23 billion. Such an increase is not out of the question but should not be banked upon.

The Scottish Government’s limited borrowing powers also mean it is unable to borrow to address any funding gap – although it is worth noting that even if it were, borrowing can only address short-term not long-term funding gaps. It is also worth remembering that following a fall-back in oil and gas prices, Scotland is set to continue to benefit from a substantially higher-than-population share of UK government borrowing over the next few years.

The Scottish Government should therefore plan on the basis of having to either hold down growth in spending or increase tax revenues to address the funding gap it has identified. This will require ruthless prioritisation of spending, and consideration of which parts of the population the Scottish Government is willing to further increase taxes on. However, it should also plan for how it would spend additional funding, if it were to become available, in order to help maximise the value-for-money achieved.

The MTFS sets out a number of high-level principles and priorities for spending, taxation, and the economy. It also recognises that when funding is tight, it may be necessary to adopt more targeted approaches to service provision than the universal approach that has been the hallmark of Scottish public policy. However, it provides no details on which specific services or programmes will be cut back – although presumably, they will be similar to those facing the biggest cuts in last May’s Spending Review: higher education, policing and justice, local government, rural affairs, and enterprise, trade and tourism promotion. Given the particularly tough outlook for next year, the Scottish Government Budget for 2024–25 will be key to understanding how the Scottish Government is tackling the funding gap it faces. It will also provide an opportunity to update the medium-term spending plans set out in last May’s Spending Review.