Last week, the Department for Education published its evidence to the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB), which will then publish its own recommendations for teacher pay in England this summer. This includes proposals for teacher pay in 2022 and 2023, which will deliver on a manifesto commitment to raise teacher starting salaries to £30,000. In this observation, we analyse how these proposals will affect levels of teacher pay and their overall affordability for schools. This comes in the context of rising and uncertain levels of inflation, particularly for energy prices, and other pressures on school budgets.

What are current plans for school funding in England?

In the 2021 Spending Review, the government set out a three-year settlement for school funding in England. The total schools budget will rise by £4 billion in 2022–23, and by a further £1.5 billion in each of 2023–24 and 2024–25. This makes for a total rise of £7 billion between 2021–22 and 2024–25. This does, however, include just over £300 million in extra funding per year to compensate schools for the extra cost of the employers’ component of the new health and social care levy from April 2021.

In our annual report on education spending, we showed that this settlement allows for a 15% cash-terms and 7.5% real-terms rise in core school spending per pupil between 2021–22 and 2024–25. This was projected to restore school spending per pupil back to 2010 levels by 2024–25.

These figures were based on inflation forecasts from Autumn 2021. Recent inflation forecasts are much higher, partly driven by rapid rises in energy prices, which have spiralled upwards further since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, the actual cost rises faced by schools will be mostly determined by the salary rises offered to school staff, with staff costs taking up more than 80% of school budgets.

What are the Department for Education’s proposals for teacher pay?

In its evidence to the STRB, the Department for Education set out its proposals for teacher salary rises in 2022 and 2023 (which apply from September of each year). This includes large rises at the bottom of the pay scale to deliver £30,000 starting salaries by 2023. In particular, the government proposes rises of 9% in 2022 and 7% in 2023 for teacher starting salaries outside of London, making for a total rise of over 16% between 2021 and 2023. The government proposes smaller salary rises of 3% in 2022 and 2% in 2023 for more experienced teachers on the ‘upper pay scale’, which account for over half of all teachers according to the Department for Education. Slightly smaller rises are proposed in London, but with the same overall approach.

This will intentionally flatten the teacher pay scale, with higher initial salaries and smaller pay rises as teachers gain more experience. This approach is based on empirical evidence showing that teachers’ decisions are more sensitive to pay and salary supplements early in their career. Teachers also have a high propensity to quit early in their career, with only about two-thirds of teachers remaining in the profession five years after qualification. A flatter salary profile may help retain newly qualified teachers. By international standards, the teacher salary schedule in the UK is also quite steep, with lower starting salaries than in many other countries. That being said, the scale of the difference in proposed pay awards by level of experience is quite stark.

In previous analysis, we showed that teacher salary levels fell by 4–5% for new and less experienced teachers between 2007 and 2021, whilst salaries fell by 8% in real terms for more experienced teachers over the same period. The smaller cuts for new and less experienced teachers reflect larger increases for such teachers in more recent years.

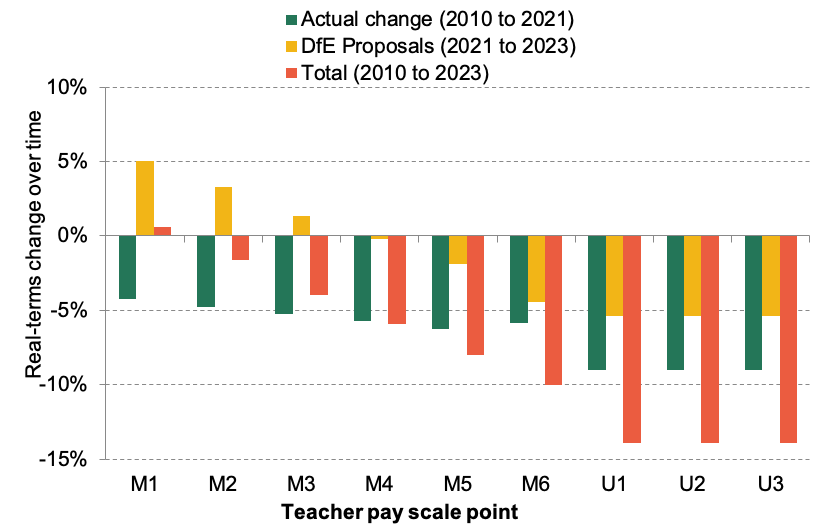

The freeze in teacher salaries in England in 2021 was part of the explanation for real-terms cuts to teacher salaries over time. However, this was calculated on the basis of an inflation forecast from Spring 2021 of under 2% in 2021–22. According to NIESR forecasts, CPI inflation is now likely to be closer to 4% in 2021–22. If we adopt this forecast, teacher salaries for more experienced teachers will have fallen by 10% since 2007 or 9% since 2010, as shown in Figure 1.

Looking to the government’s proposals for 2022 and 2023, the large proposed increases to starting salaries will allow for real-terms increases in salaries at the bottom of the pay scale, with a 5% real-terms increase in starting salaries between 2021 and 2023.

In contrast, the proposed increases of 3% in 2022 and 2% in 2023 for more experienced teachers would imply further real-terms salary cuts of 5% between 2021 and 2023. Adding this to past changes would equate to real-terms cuts of 14% between 2010 and 2023. In today’s prices, this is the equivalent of a pay cut from £46,000 to £39,000 for experienced classroom teachers at the top of the pay scale (nearly one-third of all teachers).

These are calculated on the basis of the latest NIESR forecasts for CPI inflation of 7% in 2022–23 and nearly 4% in 2023–24. There is, however, huge uncertainty about what the actual level of inflation will be as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions.

Figure 1.Real-terms changes over time in teacher salary points: actual and government proposals, actual and forecast CPI inflation

Note and source: Years refer to financial years starting each April. Teacher pay scales taken from school teachers’ pay and conditions document 2010 and 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions) and proposed scales for 2022 and 2023 taken from DfE ‘Evidence to the STRB: 2022 pay award for school staff’ (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-to-the-strb-2022-pay-award-for-school-staff). Real-terms value calculated based on average value of CPIH index (https://www.ons.gov.uk/datasets/cpih01/editions/time-series/versions/11) in the relevant financial year (e.g. 2014–15 for September 2014). Forecasts for 2021–22, 2022–23 and 2023–24 based on latest NIESR forecasts (https://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/economic-costs-russia-ukraine-conflict?type=policy-papers).

Affordability of pay rises and other pressures

A natural question to ask is whether a bigger salary rise would be affordable within the existing school funding settlement, given other pressures on school budgets. The short answer is: yes, probably a bit more.

The Department for Education estimates that each extra 1 percentage point on pay settlements for all staff (teachers and non-teaching staff) would cost schools about £250 million in the 2022–23 financial year. However, this only covers 7 months for teachers as any new salaries would apply from September 2022. The long-run full-year cost would be about £350 million.

The proposed settlement for teachers in 2022 amounts to an average pay award of just under 4% across all teachers over a full academic year (incorporating the high awards for new teachers and lower awards for more experienced teachers). Using the above figures, the government’s proposals would cost schools about £1.4 billion over a full year to deliver a 4% rise for all school staff (teaching and non-teaching staff). A higher average award of 5% would cost £1.75 billion, whilst 6% would cost about £2.1 billion.

It is highly likely that non-teaching staff will need to receive a larger average salary rise than teachers in 2022, given that the National Living Wage is rising by 6.6% in April 2022. As an approximation, one could therefore think of an average award of 6% as incorporating a lower pay award of 5% for teachers and a higher award closer to 7% for non-teaching staff. This would enable schools to fulfil their obligations to pay the new higher National Living Wage.

The £2.1 billion cost of an average award of 6% (5% for teachers and 7% for other staff) would also seem affordable within the overall school funding settlement. Excluding extra funding for the cost of the health and social care levy, school funding is due to rise by £3.7 billion in 2022–23. The £2.1 billion cost of a 6% average award would represent just under 60% of this extra funding. A 6% average award would probably allow for increases of about 4–4.5% for more experienced teachers.

This would leave about £1.6 billion to meet other pressures, such as rising energy prices and demand for spending on special educational needs and disabilities and on education recovery following the pandemic. Schools spent about £650–700 million on gas and electricity in 2019–20. This is probably now closer to £700–800 million, so a 50% rise in the cost of energy could cost schools about £400 million. The government is also due to publish a review of the special educational needs and disabilities system, which might further add to cost pressures. However, this review has been promised for nearly three years now. It is incumbent on the government to set out the conclusions and the likely cost pressures. There is also likely to be demand for extra support to help pupils recover any lost learning following on from the pandemic. But providing such support will also require a pay and remuneration package that allows schools to attract staff.

Looking to 2023, the government’s proposals amount to an average pay award of about 3% across all teachers. Based on Department for Education estimates, an average pay award of 3% across all staff would probably cost schools just over £1 billion. School funding is due to rise by £1.5 billion in 2023–24 and other pressures on school budgets are likely to continue. In contrast to 2022–23, there seems little room for a higher pay award in 2023–24 without additional funding.

Conclusion: greater risks from a low pay award

Whilst there are clear pressures on school budgets, it is also important to see the risks of further real-terms cuts to teacher pay for the ability of the system to recruit and retain high-quality teachers. During the pandemic, teacher recruitment and retention briefly improved, unsurprisingly, given the lack of other economic opportunities. However, there are already clear signs that recruitment to teacher training is now falling below 2019 levels. Further real-terms cuts to average teacher salaries could therefore be a genuine risk in terms of the system’s ability to recruit and retain high-quality teachers, and potentially hamper government efforts to level up poorer areas of the country.

In conclusion, the government’s proposals for teacher pay in 2022 and 2023 would likely deliver salary rises well below expected inflation, following on from more than a decade of overall real-terms cuts to teacher pay. A higher average pay award of 5% for teachers in 2022 (and 7% for other staff) seems affordable in the context of a £4 billion rise in school funding in 2022–23. A higher award than that proposed by the government may therefore carry fewer risks than a lower one.