Introduction

At the last election, the Conservative Party manifesto committed to increasing teacher starting salaries in England to £30,000 per year by September 2022. However, to ease pressure on school budgets and the public finances, the government has now announced a freeze on teacher pay levels in England for September 2021, and pushed back starting salaries of £30,000 to September 2023.

The level of teacher pay is important. It plays a big part in determining the recruitment and retention pressures faced by schools. With the cost of employing teachers accounting for over half of school spending, what happens to teacher salary levels also has a large bearing on the overall resource pressures faced by schools. And it is a key determinant of the material living standards for over 500,000 teachers in England.

So how has teacher pay changed over time and how sustainable is the current freeze on pay levels in England? This analysis has been supported by funding from the Nuffield Foundation as part of a wider programme of work looking at trends and challenges in education spending.

Teacher pay levels in England

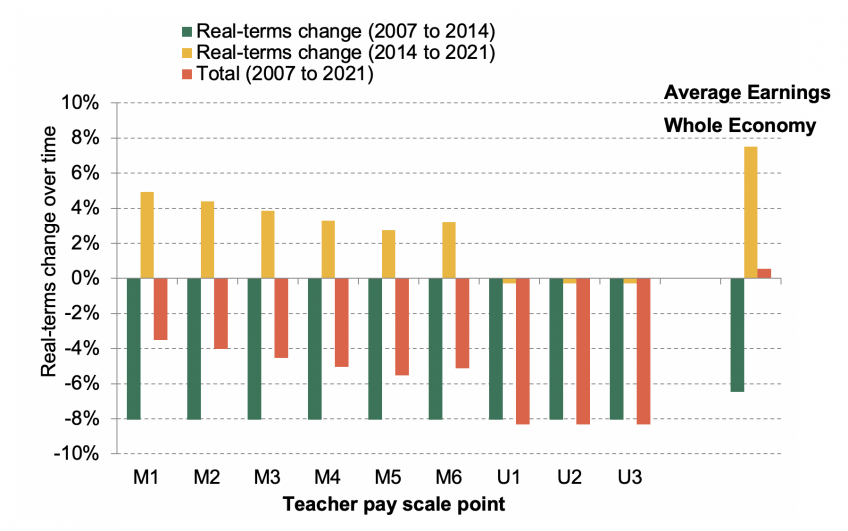

Figure 1 shows the real-terms change in teacher salary points between September 2007 and September 2021 for classroom teachers in England. Salary point M1 represents the starting salary for most newly qualified teachers (currently £25,714 in most of England) and U3 is the top of the pay scale for classroom teachers (currently £41,604). School leaders are paid according to a slightly more complicated leadership pay range. Teachers in and around London are paid higher salaries to account for a higher cost of living, particularly in inner London, but the changes over time in teacher salaries have been extremely similar across areas.

Between 2007 and 2014, there was an 8% real-terms fall in teacher pay levels right across the salary scale. There were small real-terms falls of 1% between 2007 and 2010, but even this was much better than the economy as a whole, with average real earnings falling by 3% between 2007 and 2010.

Most of the real terms drop in teacher pay can be accounted for by pay freezes and caps implemented between 2010 and 2014. These large falls mean that between 2007 and 2014, teacher pay fell by 8% in real terms, even larger than the 6.5% economy-wide fall in average earnings over that period.

Figure 1.Real-terms changes over time in teacher salary points compared with average earnings, 2007 to 2021

Note and source: Teacher pay scales taken from School Teachers Pay and Conditions Document 2007, 2012, 2014 and 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions), forecast to 2021 based on government policy of pay freeze for 2021. 2014 pay scale points are estimated based on 2012 pay scales and constant national awards of 1% for 2013 and 2014. Real-terms value calculated based on average value of CPIH index (https://www.ons.gov.uk/datasets/cpih01/editions/time-series/versions/11) in the relevant financial year (e.g. 2014-15 for September 2014). Average Earnings based on average weekly earnings for the whole economy (seasonally adjusted) (https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/averageweeklyearningsearn01). Forecasts for 2021-22 based on Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook: March 2021(https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2021/).

Between 2014 and 2021, differences begin to emerge across the salary scale. By September there will have been a 5% real-terms rise in starting salaries, the vast majority of which was driven by a large rise in 2020 as part of the move towards £30,000 starting salaries. There will have also been real-terms rises of 3-4% across the rest of the main pay range (M2-M6), which are mostly accounted for by teachers with only a few years' experience.

At the other end of the pay scale (U1-U3), more experienced teachers effectively saw a real-terms freeze between 2014 and 2021. With over half of all teachers on this part of the pay scale, this accounts for the experience of a large share of teachers.

These changes are all significantly less than the 7.5% real-terms growth in economy-wide average earnings between 2014 and 2021. Most of this growth in real earnings took place before 2020 and is not a feature of unusual patterns or data during the pandemic.

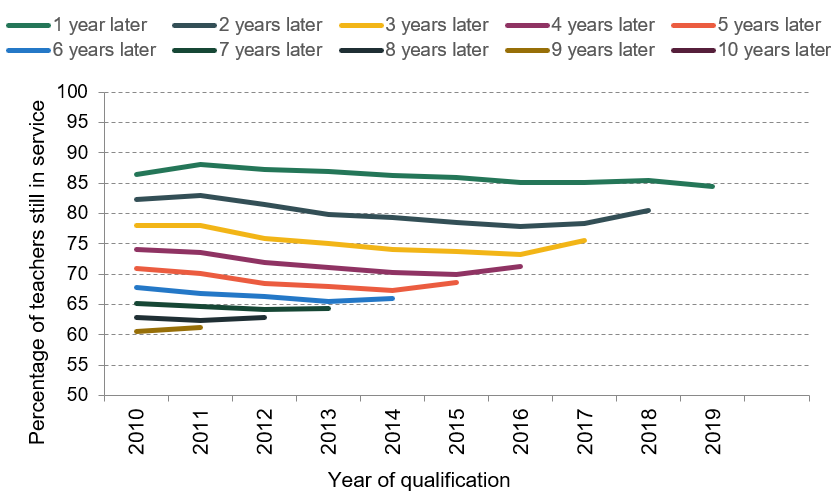

Part of the motivation for this pattern of changes is the result of a desire to counteract falling retention rates for less experienced teachers (see Figure 2) and there is good evidence to suggest that younger, less experienced teachers are more sensitive to pay levels. However, forward thinking teachers will also make career decisions based on expected pay later in their career. More experienced teachers are, almost by definition, likely to have built up significant knowledge and experience, so any reduction in retention would represent a significant loss to schools.

Seen in cash-terms, average earnings has just about managed to keep pace with inflation of 32% between 2007 and 2021, whilst the pay of more experienced teachers has only risen by 21%. The net result is that teacher salaries for new and less experienced teachers (M1-M6) are still about 4-5% lower in real-terms than 14 years earlier in 2007. More experienced teachers have seen an 8% real terms drop in salaries over this period. In contrast, average earnings across the whole economy have risen by about 0.6% in real terms between 2007 and 2021.

Following a long period of similarity, teacher pay levels are also now notably higher in Scotland and Wales. As of September 2020, starting salaries in Scotland were about £27,500, about 7% higher than in England, and £27,000 in Wales, about 5% higher than in England. The Welsh Government has already announced a further 1.75% increase in teacher salary levels for September 2021, with negotiations ongoing in Scotland. Starting salaries in Northern Ireland were lower at £24,100 in September 2020, compared with £25,700 in England, with negotiations ongoing for the September 2021 pay award.

In addition to all these changes, experienced teachers who are part of the Teacher’s Pension Scheme across the UK have seen higher rises in their employee contributions in recent years. As recently as 2011, all members of the Teachers’ Pension Scheme paid in 6.4% of their salary. In 2021, the contribution rate for less experienced teachers (earning under £28,000) was slightly higher, at 7.4%, but for those at the top of the Upper Pay Scale, it is now 9.6% of salary. These changes to contributions do not lead to higher pensions later in life, they simply reduce (in particular) the take-home pay of more experienced teachers, over and above the changes to their salaries.

Consequences for recruitment and retention

The big question is the extent to which these real-terms falls in teacher salaries have mapped into greater recruitment and retention difficulties. Figure 2 casts some light on this by showing the share of teachers still in schools by year in which they qualified and time since qualification. As one might expect, retention rates get progressively lower with time since qualification, but there has also been a decline over successive cohorts in retention rates for those with given levels of experience. For those qualifying in 2010 and 2011, around 87% were still teaching one year later, which had declined to about 85% for those qualifying in 2018 and 2019. For those with 4 years of experience, retention rates have declined from about 74% for the 2010 and 2011 cohorts to 70% for the 2014 cohort.

There was a slight recovery in retention rates for the most recent year of data, as one might expect given the limited number of employment opportunities during the pandemic. However, this only really takes retention rates back to where they were about 3-4 years ago and is likely to be short-lived if there is a recovery in outside employment opportunities. There are also signs that teachers are more likely to want to leave the profession after the pandemic.

Teacher recruitment improved during the pandemic, with teacher training applications 26% higher in February 2021 than at the same point in the previous year. However, this followed on from many years during which training numbers fell increasingly behind target, particularly in secondary schools and shortage subjects like maths and science. There are also already signs that this pandemic-related surge in applications is fading.

Figure 2. Teacher retention rates by year of qualification and years in school

Notes and source: Department for Education, School Workforce Census Statistics, November 2020 (https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england)

In summary, there have been large real-terms falls in teacher pay over the last decade and more, particularly for more experienced teachers. In 2021, teacher pay levels remain about 8% lower in real terms than in 2007, just before the financial crisis. And they are still about 4-5% lower for less experienced teachers. These represent declines relative to average earnings, which has now recovered to be just above the level seen in 2007.

There are also clear signs that these declines in teacher pay have been associated with a worsening in teacher recruitment and retention, particularly since about 2015. The pandemic has provided a temporary improvement, but there are already signs this is starting to fade.

There is some logic to the freeze in public sector pay for 2021, but this does not seem sustainable or wise for 2022 and beyond, particularly if the labour market recovers strongly. The STRB report for 2021 goes further and warns of “a severe negative impact” if the pay freeze lasts longer than a year.

If starting salaries do reach £30,000 in 2023, they will be about 8.5% higher in real terms than in 2007. Whilst that only equates to annual growth of about 0.5% per year over 16 years, that will probably still be faster than growth in average earnings over the same period. However, unless salaries for more experienced teachers grow by 13% in cash terms over the next two years, they will still be lower in real terms than in 2007, which would still be a remarkable squeeze on pay over 16 years.