Most people need to save privately for retirement if they want to enjoy a comparable standard of living in retirement to that which they have enjoyed during working life. This is particularly true of middle and higher earners, for whom a full state pension entitlement of around £9,650 a year (in 2022–23) will be less than they are used to receiving when in employment. There are concerns that many people are not saving enough. While automatic enrolment has increased the proportion of eligible private sector employees saving in a pension to around 90% (Cribb and Emmerson, 2020), the minimum default contribution rates – set at 8% of earnings between £6,240 and £50,270 – are often argued not to result in sufficient saving. Among the self-employed, only 19% were saving at all in a private pension in 2020–21 (Department for Work and Pensions, 2022), after decades of declining pension participation rates.

There is consequently important debate among policymakers, the pensions industry, and others concerned with the well-being of future generations of retirees about whether the government should seek to encourage (or compel) more saving, or more pension saving in particular, and if so how it should do that. Different policy options have been put forward, including a range of nudges targeting the self-employed, uniform increases in the automatic enrolment default contribution rate, increases in default contribution rates that depend on age, ‘auto-escalation’ whereby contribution rates increase when earnings increase, and changes to the tax treatment of pension contributions.1 This is in addition to the changes to automatic enrolment for employees that the government in 2017 committed to implementing by ‘the mid-2020s’ (Department for Work and Pensions, 2017), including reducing the lower age limit to 18 and basing minimum default contribution rates on earnings from the first pound (rather than starting at £6,240).

However, this debate around people’s ‘undersaving’, and the appropriate policy solutions, still lacks empirical evidence. One area where the evidence base has been particularly lacking is in understanding existing pension saving behaviour, including when and why pension saving changes over people’s working lives. This is important for two reasons.

First, understanding how contributions are likely to change over working life is vital for those projecting future retirement resources from current saving behaviour. For example, if people tend to increase their saving rate strongly in later working life, one needs to factor that in, otherwise projections based on early-life saving rates will underestimate future retirement resources. Second, to understand the impact of possible new policies – such as contribution rates that by default increase with age, or nudges to increase saving at particular points in life – one needs to understand how individual behaviour would respond to such circumstances in the absence of any reforms.

As a result of a recent programme of research, funded by the Nuffield Foundation and supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, we are able to contribute vital evidence to this debate. We have examined in detail how pension saving changes over working life for both employees and the self-employed, and used an economic model to illustrate how people might want to vary their pension saving as their circumstances change.

The findings of that latter strand of research, published in a separate report (Crawford, O’Brien and Sturrock, 2021), are in some ways stark. They highlight that if people are seeking to smooth their living standards over their lives, then for most people there would be good reasons to expect their desired saving rate – the proportion of income being saved for retirement – to vary considerably over working life according to their circumstances. In particular, if people know they will enjoy some earnings growth over their working life, then they would best smooth their living standards by doing more of their pension saving in middle or later life. This will be true of many young graduates. Those with children would be best served saving for retirement before their children arrive or after their children have left home. Those with student loans would be expected to increase their pension saving after those loan repayments cease as they could do so with no drop in their disposable income. Rates of return obviously matter too, with higher returns increasing the benefit to saving earlier. Finally, employer incentives are also vital. Many offered an ‘automatic enrolment style’ arrangement, where they get an employer contribution of 3% of gross pay if – but only if – they contribute 5%, might be best served by joining the pension around the start of working life and always contributing at least that minimum amount.

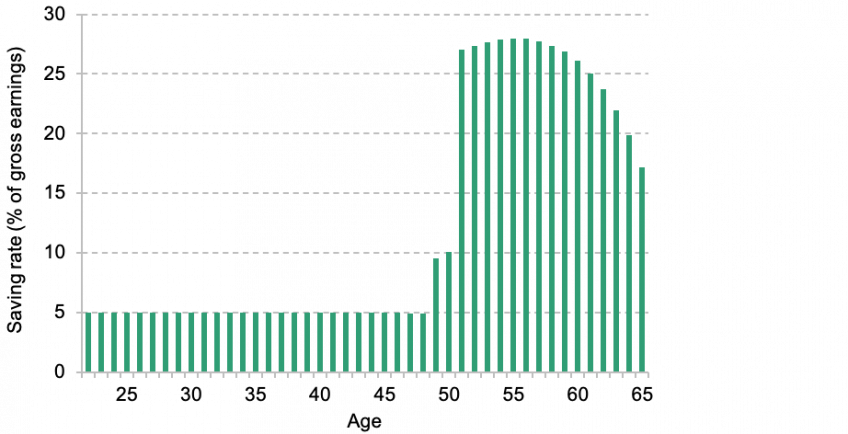

Taking all these factors together, the simulated results for a hypothetical individual (such as a graduate with (known) earnings growth, two children born at ages 30 and 32, a student loan, and a pension arrangement with minimum contributions allowed under automatic enrolment) are shown in Figure 1.1. With a 3% real return on saving, this stylised individual would best smooth their standard of living over life by joining a private pension at the start of working life and saving the minimum amount (5%) until their 50s, when they would ramp up pension saving dramatically as their children leave home and earnings are high.

People are all different and none will look exactly like this hypothetical person. Some people have children who only leave home just before their retirement or who continue to require financial support. Others enjoy little earnings growth. And for everyone there is uncertainty and risk about future earnings and employment (or the amount that can be contributed to a pension without tax penalties) which means that more saving should be done throughout life and the increase in saving in later life should be less dramatic. But the main conclusions of the modelling exercise – that pension contribution rates would be expected to change in noticeable ways as people’s circumstances change, and on average increase in later life – remain robust.

Figure 1. Simulated pension saving profile of hypothetical graduate

Note: This graduate has two children (born when the individual is aged 30/32 and who leave home at age 18), a student loan, and an ‘automatic enrolment style’ pension (employer contribution of 3% with 5% contribution from employee). The real rate of return on savings is 3%.

Source: Figure 3.10 of Crawford, O’Brien and Sturrock (2021).

The rest of the research programme has examined how people behave in practice. In general, we have focused on the pension saving behaviour of private sector employees, and saving in defined contribution workplace pension schemes, as they provide considerably more flexibility in the available choices to savers than do defined benefit schemes. An initial report on employees in this research programme (Crawford and O’Brien, 2021) suggested that even before automatic enrolment (i.e. before a large group of ‘inert’ savers were brought into workplace pensions), there was little evidence of people in general increasing their pension saving over their working lives in the way one might expect. While there was some increase in participation of defined contribution pensions, mainly among people in their 20s, the average contribution rate for those saving in a defined contribution pension only increases gradually over working life, by around 5 percentage points of gross pay between the early 20s and late 50s.

In this report, we present the results of our detailed research that has sought to unpick when and why employees change their pension saving. In Chapter 2 we look at the relationship between earnings and contributions for employees, and whether there is any association with age over and above the fact that earnings tend to increase as people age. In Chapter 3 we examine whether employees respond to some aspects of the pensions tax incentive to save in a pension. In Chapter 4 we examine whether pension contributions change in response to wider changes in household circumstances. In Chapter 5 we conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings for policy going forwards. In an accompanying report, Cribb and Karjalainen (2023) examine similar issues for self-employed workers using administrative tax data from HMRC.

Key findings

- Changing employer significantly increases the probability of private sector employees starting and stopping saving in a workplace pension. Between 2019 and 2020, 27% of private sector employees who save in a pension and then change employer stop saving in a workplace pension (at least temporarily), compared with just 7% of those who do not change employer. Furthermore, 53% of those who previously were not saving in a pension and subsequently change employer start saving in a workplace pension, compared with 23% of those not saving in a pension who do not change employer.

- Comparisons with 2005–12 suggest that automatic enrolment has significantly changed how moving employer affects workplace pension participation. In particular, a much higher share of private sector employees, 54% (versus 27%), used to stop saving in a workplace pension when changing employer prior to automatic enrolment. At the same time, starting to save in a workplace pension when changing employer is much more common in 2019–20 than in 2005–12.

- Changes in earnings only have a small effect on pension saving decisions, despite strong theoretical reasons for them to be linked. In 2005–12, before automatic enrolment was rolled out, a 10% increase in real earnings over five years is associated with only around a 1 percentage point increase in the probability of joining a pension among those aged 22–29, falling to an even smaller 0.2–0.6ppt increase in the probability of joining a pension among those aged 50–59. We find changes in earnings still have a small effect on pension participation in 2019–20, except for when they lead to someone earning at least £10,000 a year and their employer therefore being required to enrol them automatically into a workplace pension.

- Higher minimum employee contributions for higher earners, or a form of ‘auto-escalation’ – that is, for default pension contribution rates to increase alongside increases in earnings – could therefore nudge people to make better pension saving decisions. There are good reasons for many people to make higher pension contributions in years when their earnings are higher in order to smooth their living standards over their life, but our results suggest that people are currently only making small changes in pension contribution rates as earnings rise.

- There is little evidence of people changing their pension saving at any particular ‘trigger age’. Before automatic enrolment, the probabilities of pension savers increasing or decreasing their pension contribution rate by more than 1% of earnings over the course of a year are around 12% and 8%, respectively, and vary little with age.

- Workplace pension participation responds only slightly to the increase in the up-front tax incentive for pension saving at the higher-rate threshold. Prior to automatic enrolment, if employees earning £60,000 received 20% up-front income tax relief on their pension saving (rather than 40%), then pension participation would fall by 1 percentage point, from 60% to 59%. This is only a very small change in participation for a large change in the up-front tax incentive.

- Pension contribution rates also only respond mildly to this tax incentive. Taking an employee earning £60,000 per year and contributing £3,000 per year into their pension, we find that prior to automatic enrolment they contribute only about £75 more into their pension per year because they receive up-front tax relief of 40% rather than 20% on pension saving.

- If anything, pension saving has become even less responsive to this tax incentive since the roll-out of automatic enrolment. This is consistent with automatic enrolment bringing more ‘passive savers’ into workplace pension saving. Further increasing tax incentives for pension saving might therefore not be a cost-effective way of boosting retirement saving, though this work does not provide evidence on how saving might respond to substantial changes in the structure of pensions taxation.

- We analyse how pension saving is affected by different life events – namely, changes in the number of dependent children at home, housing tenure, marital status, and whether someone’s partner is in paid work or not. We find that these significant events in people’s lives generally have little impact on private sector employees’ pension participation and contribution rates.

- This is despite most of these life events being associated with large changes in spending commitments, income or the cost of living, making them a good time to change pension saving. For example, paying off your mortgage is associated with a large increase in disposable income – and therefore we might think many people would want to put more in their pension after this point than before it.

- We do find that pension contributions tend to increase by around 0.4% of pay more when people move from renting to having a mortgage (which in recent years has been associated with a decrease in spending needs and therefore more disposable income). This could also be consistent with no longer needing to save for a deposit.

- Pension contributions tend to increase by around 0.3% of pay less after the arrival of a first child (which is typically associated with an increase in spending needs). The magnitude of this effect is slightly larger for women, at 0.5% of pay, than for men (for whom the effect is 0.2% of pay and not statistically significantly different from zero).

- These findings suggest that nudging employees to change their pension saving around major life events could have desirable effects. One example would be for mortgage providers to ask their customers in advance how much of their mortgage repayments they would like to divert into their pension when their mortgage term ends, and making it as easy as possible to achieve this.