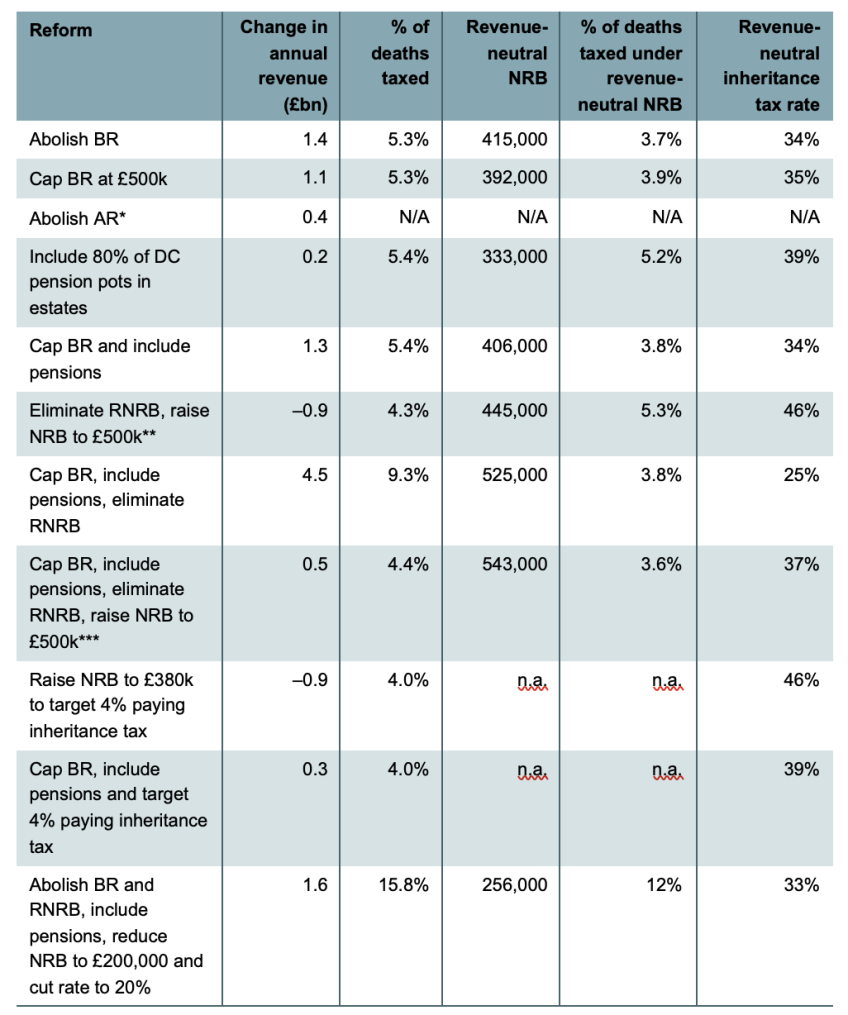

Key findings

1. Inherited wealth is growing – and set to continue to grow – compared with earned incomes, and it will have a growing impact on inequalities by parental background. While inheritances will remain small for those with the least wealthy fifth of parents, for those with the wealthiest fifth of parents they are set to rise from averaging 17% of lifetime income for those born in the 1960s, to averaging 30% of lifetime income for those born in the 1980s. If the annual flow of non-spousal inheritances next year was equally shared across those aged 25, this would imply each receiving around £120,000.

2. Exemption thresholds, which allow many couples to pass on up to £1 million tax-free, mean that the share of deaths resulting in inheritance tax is small, at around 4% in 2020–21, but a larger and growing proportion are potentially affected by the tax. The proportion of deaths resulting in inheritance tax is set to grow to over 7% by 2032–33. The number of people affected by inheritance tax will be still larger. By 2032–33, one in eight people (12%) will have inheritance tax due either on their death or their spouse or civil partner’s death.

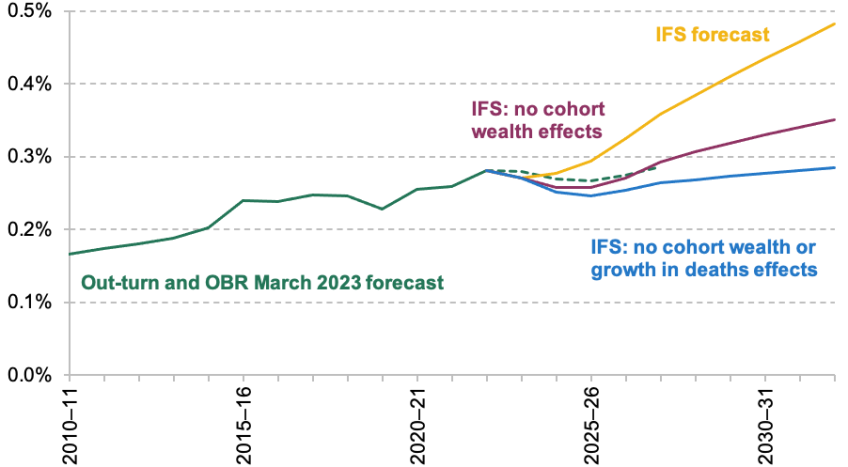

3. Inheritance tax revenues are small, at £7 billion (or 0.3% of GDP) a year. However, we forecast that by 2032–33 they will rise to just over £15 billion in today’s prices (0.5% of GDP), driven by increasing levels of wealth held by subsequent generations of retirees. It is of growing importance that this tax is well designed.

4. The current cost of abolishing inheritance tax would be £7 billion. Around half (47%) of the benefit would go to those with estates of £2.1 million or more at death, who make up the top 1% of estates and would benefit from an average tax cut of around £1.1 million. The 90% or so of estates not paying inheritance tax would not be directly affected by such a reform.

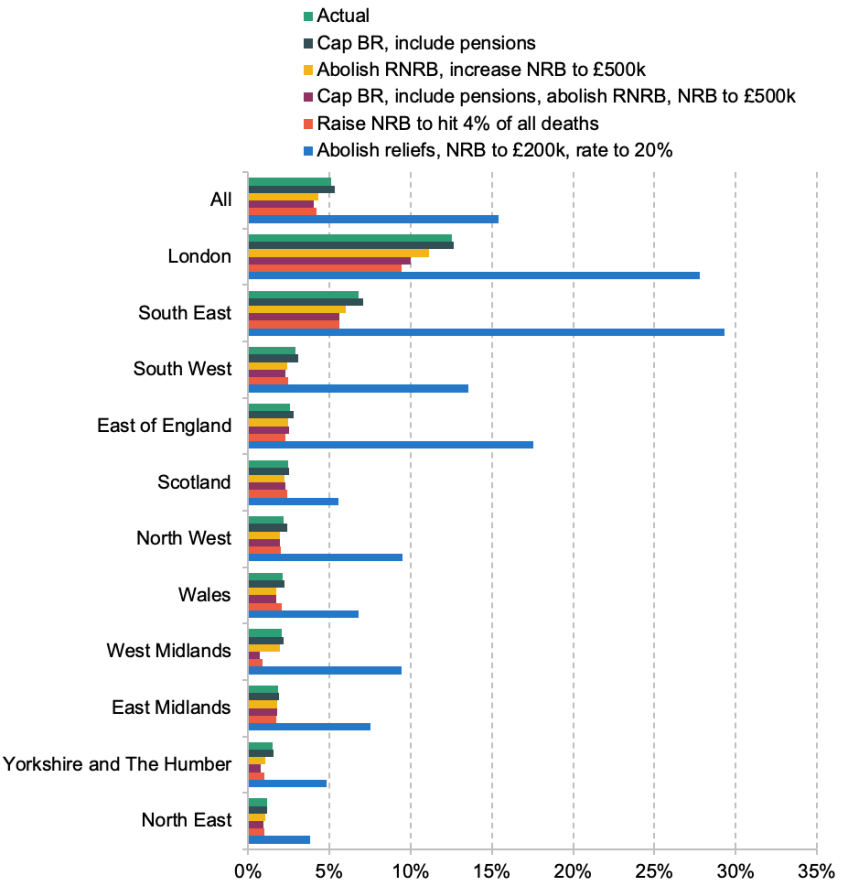

5. There are several problems with the current design of inheritance taxation.Reliefs for agricultural and business assets and certain classes of shares, and the total exemption of pension pots from inheritance tax, open up channels to avoid the tax and are consequently costly and inequitable and distort economic decisions. The residence nil-rate band, which gives special treatment to property passed to direct descendants, raises similar types of problems and is of greater benefit to those in London and the South. There is a clear case for eliminating the special treatment of all of these types of assets.

6. Abolishing agricultural and business reliefs and bringing pension pots within the scope of inheritance tax could raise up to around £1½ billion a year. How much revenue would be raised is uncertain and depends on various factors including whether other channels are used to avoid inheritance tax. Making these changes together would reduce the scope for substituting one avoidance channel for another.

7. Four-fifths of the tax revenue from reform to business relief could be captured just by capping the relief at £500,000 per person, rather than outright abolition. Most business wealth is concentrated among those with high wealth, so the fiscal cost of an additional half a million pounds threshold for business wealth would be low, though the special treatment would remain unfair and distortionary. Around 90% of business wealth bequeathed is given as part of an estate worth over £2 million.

8. Removing the special treatment for residential property, by abolishing the residence nil-rate band (currently set at £175,000) and extending the nil-rate band from £325,000 to £500,000 would cost around £700 million a year and hold the proportion of deaths resulting in inheritance tax down at around 4%, while making the tax system fairer.

9. A reform that capped agricultural and business reliefs, brought pension pots within the scope of inheritance tax and abolished the residence nil-rate band could fund an increase in the nil-rate band to around £525,000 or a cut in the inheritance tax rate from 40% to around 25%.

10. Increasing the nil-rate band to hold the share of deaths resulting in inheritance tax down at its long-run average of 4% would require a nil-rate band of £380,000 and cost around £900 million a year. The cost of limiting the scope of the inheritance tax system in this way would grow over time, reaching £2.7 billion by 2032–33.

11. There are other changes to taxation at death that would improve efficiency and fairness, and raise revenue. Levying capital gains tax at the point of death would raise around £1.6 billion a year. Levying income tax on withdrawals from inherited pension pots regardless of the age at which the giver passed away would also raise further revenue.

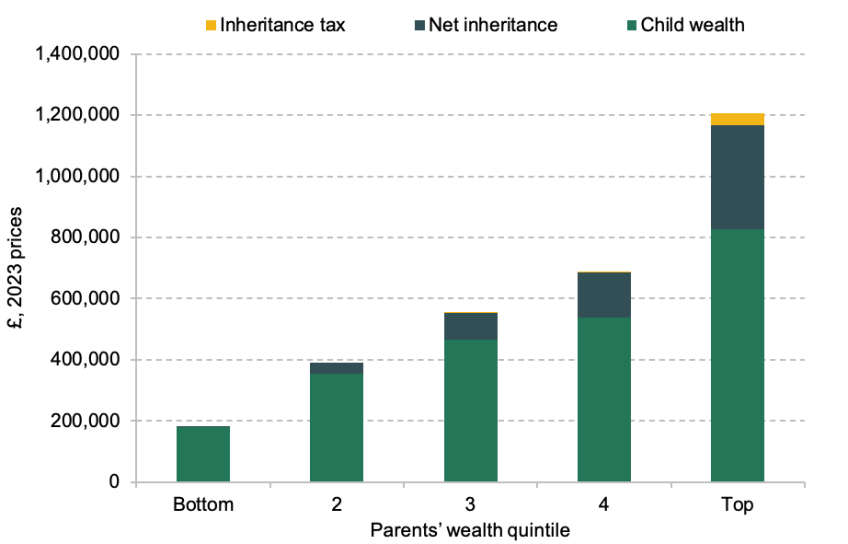

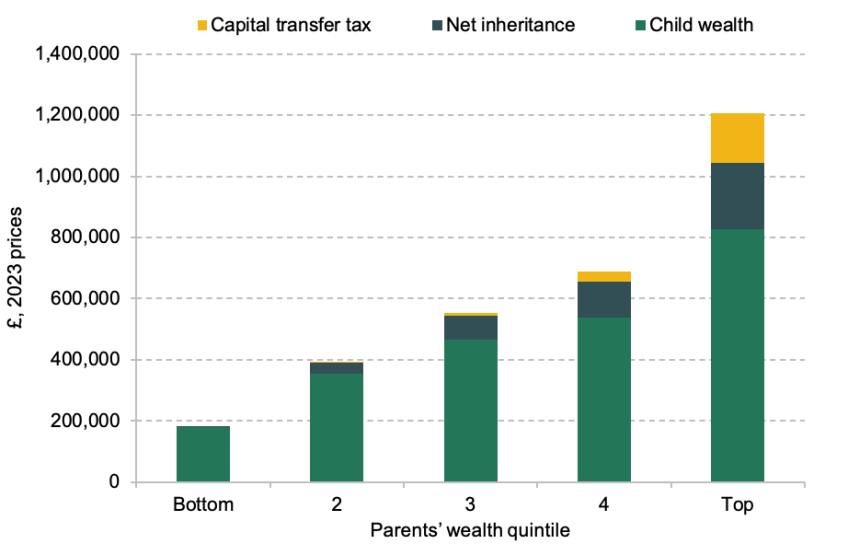

12. Inheritance tax as currently designed has only a small impact on the distribution of inheritances received and therefore on intergenerational wealth mobility. The wealthiest fifth of donors will bequeath an average of around £380,000 per child, and pay inheritance tax of around 10% of this amount. By contrast, the least wealthy fifth of parents will leave less than £2,000 per child. To have a larger impact on intergenerational mobility, inheritance tax would have to be substantially expanded in scope.

13. By the time inheritances are received, wealth inequality is already substantial. Inheritances are most often received when people are in their late 50s or early 60s. Around the ages of 50–54, children of the wealthiest fifth of parents have an average of £830,000 in wealth, while children of the least wealthy fifth have on average £180,000. While a reformed inheritance tax could do more to promote intergenerational mobility, big wealth inequalities by parental background already exist before inheritances are received.

7.1. Introduction

Inheritance tax is arguably the UK’s most disliked tax. A recent YouGov poll found that just 20% of people deemed inheritance tax ‘fair’ (see Ansell (2023)). This compared with almost 60% for National Insurance contributions. There is near-universal agreement that inheritance tax in its current form needs reform, but no consensus about what that reform should be. Complaints range from saying that the tax is far too easy to avoid – because of exemptions for certain types of assets and for gifts made more than seven years before death – and so needs to be expanded, to claims that there is no justification for (further) taxing those who choose to pass on their wealth to their children and that the tax should be abolished.

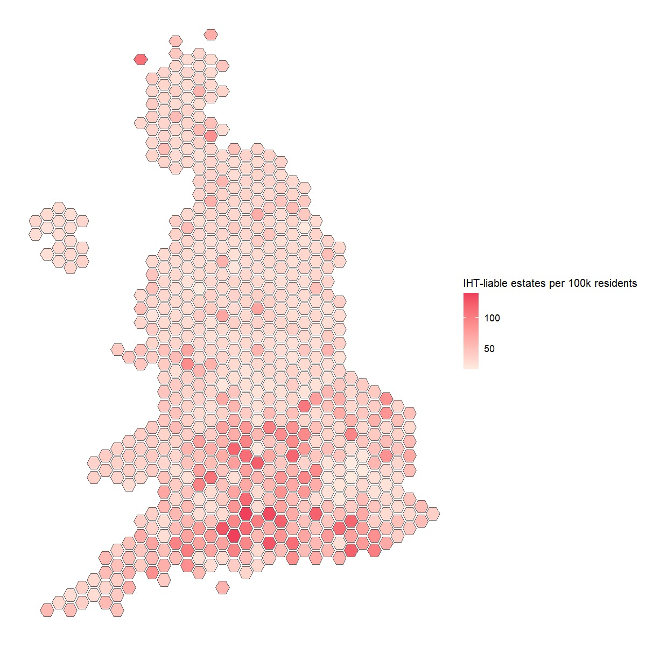

Figure 7.1. Number of inheritance-tax-liable estates per 100,000 residents, by parliamentary constituency

There are a number of well-noted and established issues with the current design of inheritance tax and indeed with the way that the tax system treats death more generally. These have been set out by, for example, the Office of Tax Simplification (2019) and the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Inheritance and Intergenerational Fairness (2020). There is good reason to think that reform could make the tax system fairer and more economically efficient.

Reform of inheritance tax is a topic worth considering now for multiple reasons. In the immediate term, a group of Conservative MPs, in consort with a Daily Telegraph campaign, have sought to push the Chancellor to commit to abolishing the tax. Looking to the near future, governments of all stripes may seek to raise more revenues from taxing wealth and wealth transfers in order to meet fiscal pressures. There are many political considerations that bear on choices around inheritance tax, not least its unequal effects across the country. Figure 7.1 shows that there are far more inheritance-tax-liable estates per resident in the South of England.

Taking a longer-term view, the rapid growth of wealth compared with earnings over the past several decades has brought with it questions about the balance of taxation across generations and the growing role of parental wealth transfers in driving differences in life outcomes within today’s working-age generations. Inheritances have grown, and are expected to continue to grow, faster than earnings, meaning that they are projected to have a growing negative impact on intergenerational mobility (van der Erve et al., 2023). Put simply, it is becoming harder to use savings from earnings to make up for a lack of inheritance relative to others born at the same time. Questions around how inheritances should best be taxed will become more pressing with time.

In this chapter, we consider problems with the current design of inheritance tax, examine the revenue and distributional consequences of potential reforms, and discuss some wider issues about how the tax system operates at death. Our focus is on incremental reforms which build on the current structure of inheritance tax, although we note areas where more fundamental reform could be considered. We consider some reforms that expand the tax base and eliminate exemptions for certain types of assets. We also analyse the effects of reforms that would take some estates out of paying inheritance tax, including increasing tax-free thresholds and complete abolition of the tax. We show combinations of reforms that would bring certain assets into the inheritance tax base while at the same time reducing the tax liability for some. Our options encompass some that raise revenue, some that would reduce it and some that are revenue-neutral. While our focus is on inheritance tax, we also note some other ways in which taxation around the point of death should be reformed.

Section 7.2 sets out how inheritance tax currently works and Section 7.3 discusses the economic trends relevant to inheritances and inheritance tax. Section 7.4 outlines some principles of how an inheritance tax should be structured, with Section 7.5 discussing some problems with the current system’s design. Section 7.6 quantifies the impacts of reform options. Readers should note that our policy costing estimates are quite uncertain and should in general be treated as indicative, because (i) the data we use have less good coverage of the very wealthiest, (ii) assets in the data do not map directly onto some of the reliefs present in inheritance tax, and (iii) we do not directly observe all gifts and transfers that people make. Section 7.7 lays out our recommendations for reform and concludes. Readers interested only in the effects of reforms and policy recommendations could begin reading at Section 7.6.

7.2. How does inheritance tax work?

Inheritance tax is a tax on the value of the ‘net estate’ when someone dies, i.e. it is a tax on the value of all the assets they own, less all the debts that they have, after accounting for exemptions. Gifts made within seven years of the death of the giver are also counted as part of the giver’s estate, while those made more than seven years before death are not. There is no tax on the first £325,000 of net assets, while a 40% rate applies above this ‘nil-rate band’ (with lower rates applicable for gifts made three or more years in advance of death). Where assets are transferred to a spouse or civil partner, they are generally exempted.

There are two common reliefs that mean that in practice the threshold for many is much higher than £325,000. First, there is a ‘residence nil-rate band’. This provides an additional exemption for the first £175,000 of residential property, as long as the property is passed to direct descendants. The implication is that for many older people, there is no tax on the first £500,000 of net assets. For more valuable estates, worth more than £2 million, the residence nil-rate band is tapered away. For every additional £1 the estate is worth above £2 million, the residence nil-rate band is reduced by 50p, effectively increasing the marginal tax rate on each £1 of assets to 60p between £2 million and £2.35 million.

Second, there is the ‘transferable nil-rate band’. Where assets are transferred on death to a spouse or civil partner, any unused portions of the ordinary and residence nil-rate bands are also transferred to the surviving partner. This means that on the death of the second spouse, for the vast majority, up to £1 million in assets can be passed on tax-free. Largely as a consequence of these reliefs, HMRC statistics show that only 2.1% of estates at death worth under £1 million paid any inheritance tax in 2020–21.

The complexities of the treatment of these various exemptions mean that the practical threshold of £1 million for the vast majority of couples is not always understood. While 16% of adults have individual non-pension wealth exceeding £325,000, only 8% of adults live in a family with non-pension wealth above £1 million. That said, among those in their 60s, 13% have family non-pension wealth of £1 million or more. Some of these assets will be spent prior to death, but, in conjunction with the fact that the nil-rate band threshold has generally been increased over time – or other reforms that take individuals out of tax introduced – this might mean that a higher proportion of people consider themselves potentially subject to inheritance tax than actually end up paying the tax.

As will be further discussed below, transfers of certain types of assets either are not counted as part of estates for inheritance tax purposes or are given further exemptions. This means that the effective tax rate can be lower – and in some cases much lower – than would be implied if only the above exemptions applied.

7.3. The outlook for inheritances and inheritance tax

The growth of inheritances

Recent decades have seen the flow of inheritances increase substantially compared with national income. The annual flow of non-spousal inheritances is estimated to have increased from 5% to 8% of GDP between the early 1980s and mid 2000s (Alvaredo et al., 2017; Atkinson, 2018) and has likely continued growing since then. If the annual flow of inheritances was equally shared across those aged 25, this would imply a transfer to each person of around £120,000.

This increase in inheritances happened partly because of the expansion of private ownership of housing over time and across generations. While only 40% of those born around the turn of the 20th century owned their own home at age 70, this increased to over 70% of those born from the 1930s onwards (Corlett and Judge, 2017). This means that, over time, a greater share of those dying have had some property wealth to bequeath. In addition, the value of wealth has increased rapidly compared with GDP in recent decades, meaning the value of assets passed on at death has risen compared with people’s incomes. Average house prices increased from around four times average household incomes in the early 1990s to around eight times at the eve of the financial crisis and have stayed around this level since then.

Recent research at IFS has found that in the coming decades, the size of inheritances is likely to increase further, as compared with the incomes of receivers (Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2021). There are several reasons to expect this further increase in the importance of inherited wealth in future years. First, subsequent generations of older households are significantly wealthier than those that went before them, even when compared at the same point in their life cycle. For example, those who were born in the 1940s, and therefore aged between 73 and 83 today, on average had almost £100,000 or about 30% more household wealth (in real terms) when in their early 70s than did those born in the 1930s. Similarly, the 1950s-born generation, now largely into retirement, is about 25% wealthier, on average, than the 1940s-born generation (Sturrock, 2023). As the drawdown of non-pension wealth at older ages is typically modest (Crawford, 2018a and 2018b), we can therefore expect more wealth to be passed down by each generation that comes to the end of life in the coming decades.

The second reason that inheritances can be expected to increase compared with the incomes of receivers is that the number of children per person is decreasing as we look across the generations of older people. That is to say that each generation of younger people, i.e. future inheritors, will have to share their parents’ estate with fewer siblings. Those born in the 1980s have on average 1.8 siblings, compared with 2.0 and 2.5 for those born in the 1970s and 1960s respectively (Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2020). Even without an increase in the value of estates at death then, assuming all wealth is given to a direct descendent, this would drive a 25% increase in the average inheritance received between those born in the 1960s and those born in the 1980s.

Finally, while these two aforementioned factors would be expected to drive an increase in the size of inheritances received in absolute terms, a lack of growth of non-inherited wealth and earnings across receiving generations will mean that these inheritances are set to be an increasing share of lifetime resources for subsequent generations of inheritors (Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2021). In other words, it is becoming more difficult for younger generations to accumulate wealth through non-inherited means. While earnings during working life were around 30% higher in real terms for the 1940s-born generation than for the 1930s-born on average, this rate of increase has stagnated in recent decades and the 1980s-born generation has remarkably started working life with lower average earnings than their predecessors (Sturrock, 2023). This has driven a similar stagnation in wealth accumulation of younger generations. Consequently, inheritances are expected to double in importance in the coming decades, rising from 9% of lifetime income for someone born in the 1960s to 16% for someone born in the 1980s (Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2021). There is, of course, huge uncertainty around any such projections. The last year has, for example, seen the outlook for interest rates and asset prices change substantially, such that the wealth to income ratio is now expected to decline in the coming years (Broome, Mulheirn and Pittaway, 2023). Nevertheless, it would take huge changes in the economic outlook or in individual behaviour to offset the trends that are expected to lead to an increased importance of inheritances. While the magnitudes are uncertain, it is probably safe to say that, absent a very large shock, inherited wealth will be of growing importance across generations of young people in the coming years and decades.

Implications for inequality and social mobility

One of the commonly discussed concerns about the growth of inheritances, and one of the main normative justifications given for an inheritance tax, is that inheritances will reduce social mobility.

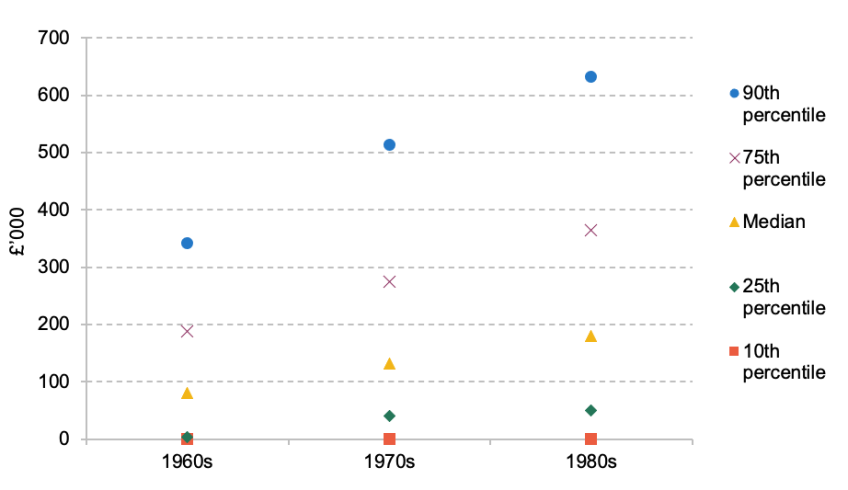

Younger generations are expected to inherit increasingly large sums as a whole. However, these will not be equally spread. Within each generation of older people, there is a substantial minority who do not own their own home and have minimal other bequeathable wealth. Their children therefore cannot expect to receive any substantial inheritance. As shown in Figure 7.2, while the parents of someone born in the 1980s has wealth per heir of around £180,000 at the median, over 10% of parents have no wealth to bequeath. At the upper end, 25% of individuals have parents with wealth per heir of over £360,000, with the top 10% richest parents having over £600,000 to potentially leave to each heir.

Figure 7.2. Distribution of per-heir parental wealth at parental age 65, by decade of birth

Source: Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2020. Uprated to 2023 prices.

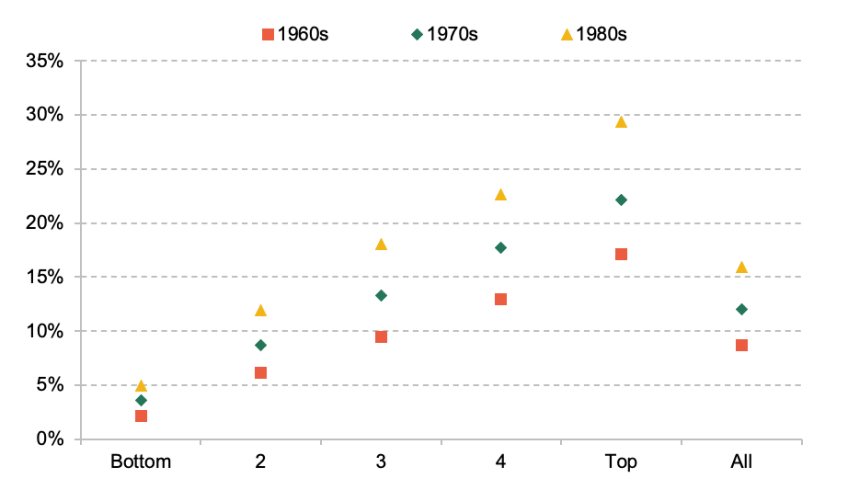

Figure 7.3. Median inheritance as a percentage of lifetime (excluding inheritance) net income, by parental wealth quintile and decade of birth

Source: Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2021.

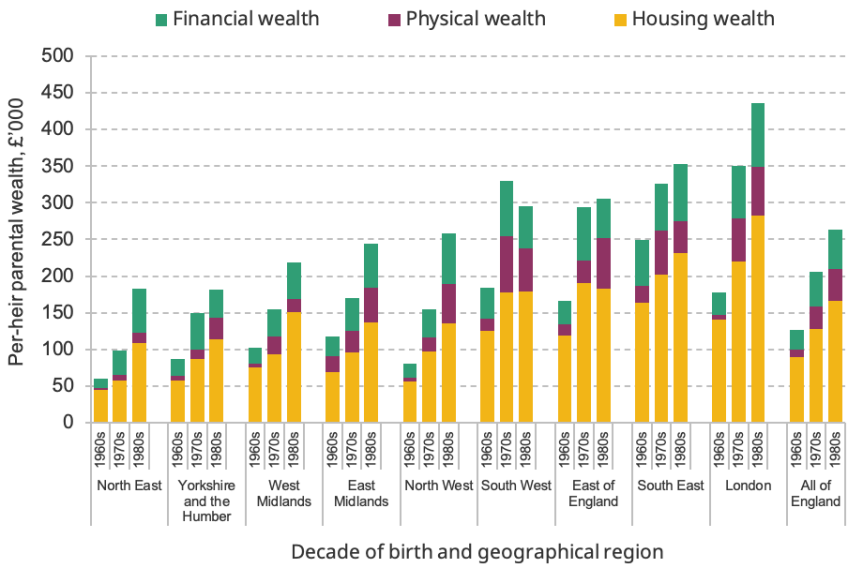

Figure 7.4. Per-heir parental wealth by decade of birth and region

Source: Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock, 2020. Uprated to 2023 prices.

Together with the growing importance of inheritance as a part of lifetime economic resources, this inequality in future inheritances means that parental wealth is set to be a greater driver of lifetime income across younger generations. Figure 7.3, taken from Bourquin, Joyce and Sturrock (2021), shows the growing impact that inheritances are projected to have on differences in lifetime income between those with wealthy and less-wealthy parents. Bourquin et al. projected that while inheritances would make up less than 5% of the value of non-inheritance lifetime income for those with the least-wealthy fifth of parents in each of the 1960s-, 1970s- and 1980s-born generations, they will be of growing importance for those with the wealthiest parents, rising from 17% of lifetime income for those born in the 1960s and with parents in the wealthiest fifth to almost 30% of lifetime income for those born in the 1980s. In other words, whether you have high or low lifetime income is set to become more related to your parental background in the future than it is today or was in recent decades.

Inheritances will also vary substantially by where you grew up because of the strong geographical pattern to wealth levels. According to Nationwide regional house price data, average house prices in London in the second quarter of 2023 were £517,000. This compares with £154,000 in the North-East of England. Figure 7.4 shows that the expansion of parental wealth, combined with this geographical difference in wealth levels, means there is an expanding gap in parental wealth – and therefore potential future inheritances – between those with parents living in different parts of the country. Notably, the gap between those with parents in London and the rest of the country has opened up across generations. Among those born in the 1960s, total parental wealth per heir was around £175,000 for those whose parents lived in London. This was comparable to figures for the East of England and the South West and was only around £50,000 more than the figure for the whole of England. For the 1980s-born generation, wealth per heir for those with parents living in London is around £440,000, by far the highest of any English region. This is over £170,000 higher than per-heir wealth for England as a whole and £250,000 higher than the figure for the North-East.

There are also important ethnic differences in parental wealth. Among those aged 25–39, around 75% of white individuals and around 85% of Indian individuals have homeowning parents, compared with less than 50% of black Caribbean young people (van der Erve et al., 2023). Ethnic minority groups are under-represented at the upper end of the wealth distribution. Just 6% of Indian people are in the top 15% of the wealth distribution, as are 4% of black people and 2% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi people. While part of these differences is accounted for by the different age distributions of ethnic groups, significant gaps from the white majority remain even once this is accounted for (Bourquin, Brewer and Wernham, 2022).

Implications for inheritance tax revenues

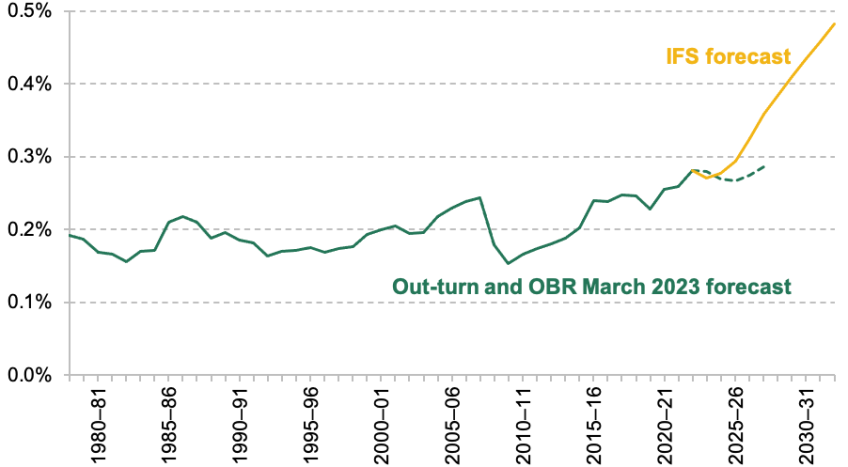

Inheritance tax revenues are modest in size and only a small portion of overall government revenues (0.7% of revenues in 2022–23). As inheritances have risen compared with GDP, inheritance tax revenues have also risen modestly as a share of GDP. They have risen from around 0.2% of GDP in the 1980s and 1990s to 0.28% of GDP in 2022–23 (Figure 7.5). The increase in inheritance tax revenues has been tempered by changes to the parameters of inheritance tax that have made the system more generous. In 2007, the transferable nil-rate band was introduced, meaning that spouses (and civil partners) could transfer unused portions of their nil-rate band to their surviving partner. The residence nil-rate band was phased in from April 2017, moderating the increase in revenues between 2017–18 and 2020–21.

Looking forward, over the next five years, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that inheritance tax revenues will be broadly flat as a share of GDP, falling then rising slightly, in line with the outlook for house prices. In order to look further into the future, we make a projection of inheritance tax revenues up to 2032–33. We find that the increase in wealth levels held by successive generations of older people can be expected to translate into rising revenues as a share of GDP. While the OBR forecasts that revenues will rise from £7.2 billion in 2023–24 to £8.4 billion in 2027–28 (worth £8.2 billion in 2023 prices), we forecast that they will rise to £10.3 billion (in 2023 prices) by 2027–28, a difference of £2.1 billion in 2027–28 or 26% of revenues. In other words, the additional revenue that we forecast would, if correct, be sufficient for the Chancellor to cut the rate of inheritance tax from 40% to 32%. Without that change, we forecast that revenues will then continue to rise to £15.3 billion (in 2023 prices) by 2032–33, or 0.48% of GDP.

Figure 7.5. Inheritance tax revenues as a percentage of GDP

Note: Includes estate duty and capital transfer tax, the predecessors of inheritance tax. Dashed line indicates OBR forecast. Yellow line indicates IFS forecast.

Source: OBR’s March 2023 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, IFS revenues composition spreadsheet, and authors’ calculations using the Wealth and Assets Survey.

In terms of the number of people affected by inheritance tax, the most recent HMRC statistics show less than 4% of estates paid inheritance tax in 2020–21. However, the rapid growth in wealth among older individuals means this number is set to rise to over 7% by 2032–33. The number of people affected by inheritance tax will be still larger. One in eight people (12%) will have inheritance tax due either on their death or their spouse or civil partner’s death by 2032–33. This varies dramatically between the different regions of the country: in London, around 23% of people (or their surviving spouse or civil partner) will pay inheritance tax in 2032–33, almost twice the national average and five times higher than in the North East.

In making this projection, we use the OBR’s assumptions for the growth in asset prices and nominal GDP to project forward the wealth holdings of older people that are measured in the Wealth and Assets Survey. In addition to changes in wealth due to asset price changes, we assume modest drawdown on wealth as households age, at a rate of 2% per year for housing wealth and 3% for other taxable wealth. We use Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality rates that vary by age and sex to project which individuals will pass away and bequeath their wealth, assuming that the first of those to die in couples bequeaths all wealth to their surviving spouse or civil partner. We apply the inheritance tax system to projected estates, assuming that the nominal freeze of inheritance tax thresholds comes to an end in April 2028 and that thresholds are uprated in line with CPI inflation thereafter, in line with stated government policy. The main reason that we project substantially more growth in inheritance tax revenues than the OBR is that we take account of the fact that subsequent generations have higher wealth holdings whereas the OBR forecast does not. We further discuss our method and compare it with the OBR’s forecast in Appendix 7A.

7.4. Principles of inheritance taxation

The arguments for and against taxation of wealth transfers – and around how and to what extent these transfers should be taxed – are complex. The economic issues that bear on this question include why people make wealth transfers and how transfer choices respond to taxation, and the evidence here is far from conclusive. What policy should be implemented also depends heavily on the normative principles of policymakers. We do not seek to review all of the arguments here. Instead, we outline what economic principles would suggest about the design of a system of taxation of wealth transfers, if one is in place. For comprehensive discussion of the issues around wealth transfer taxation, see Boadway, Chamberlain and Emmerson (2010) and Kopczuk (2013).

The treatment of different types of assets

There is a strong case that if there is an inheritance tax then it should apply in the same way across all forms of wealth inherited. There are two reasons for this. The first is one of equitable treatment between those who do (and perhaps are more able to) transfer wealth in some forms rather than another. The second is an argument from economic efficiency. When choosing the form in which to hold their wealth, people will consider a range of factors including the ease of access or hassle involved with holding wealth in some forms, the financial return they can obtain, including how risky that return is, and the tax treatment of that asset. When some assets are treated differently by the tax system from others, this has the potential to distort decisions so that wealth is not held in the way that will maximise its economic returns, subject to the needs of the holder of that wealth. This may mean that investment decisions in the wider economy are also impacted, with the potential for investments with higher societal benefits to be forgone because others are more favourably treated by the inheritance tax system. Arguments are sometimes made in favour of exempting some assets, such as businesses, but on balance we do not believe the arguments here are strong, as discussed in the next section. Efficiency arguments for exemptions, based on a desire to encourage investment in particular asset classes, are also inconsistent where they do not apply to the asset returns, merely on transfer.

The treatment of transfers made at different points in time

On the face of it, there is a strong case that the tax system should treat gifts made while alive in the same way as wealth transfers at the point of death, and that is the approach taken in many countries with some form of wealth transfer taxation. The arguments come from equity of treatment of those able and not able to make such gifts, and from efficiency, because of the potential for gifts to be used to avoid inheritance tax, if not taxed. There are also arguments in favour of a lower tax rate on lifetime gifts than on inheritances. First, at least some of the wealth left at death may not be intentionally left to heirs but instead be merely wealth unspent as a result of uncertainty about the lifespan of the deceased or their inability to access and run down housing equity. Taxing such inheritances will not lead to a change in economic behaviour and will therefore be a way of the government raising revenue without causing costly economic distortions. The same cannot be said of gifts which are intentionally made. Second, gifts may respond to the needs of the receiver to a greater extent than inheritances and so discouraging them may be more costly. However, the extent to which bequests are left intentionally or unintentionally is hard to estimate – using whether or not they are made at death is a rather crude proxy – and large gifts do not appear to respond substantially to receivers’ financial circumstances (Boileau and Sturrock, 2023b; Groot, Möhlmann and Sturrock, 2022). There is therefore a strong case in practice for preventing lifetime gifts from being used for inheritance tax avoidance by including them within estates (or taxing them when made).

Whether tax should be levied on estates bequeathed or on inheritances received

Inheritance tax is oddly named because it is a tax on the estate of the deceased rather than being levied on the wealth received (the ‘inheritance’). The distinction is important because levying a tax on the receiver allows the tax to vary by their circumstances, including their other sources of wealth and income. That is, it would allow for a transfer of £500,000 to a millionaire to be taxed differently from a transfer of £500,000 from the same estate to someone who is poor. There are arguments in favour of taxes levied on estates and in favour of taxes levied on inheritances, and these depend on the ultimate justification for taxing wealth transfers. We note here that if the aim of an inheritance tax is to reduce the effect of inherited wealth on inequalities in economic resources between those with richer and poorer parents, then it would make sense for that tax to vary according to the other economic resources of the receivers of inheritances. Under such a system, one might wish to levy taxes based on the lifetime receipt of wealth transfers. Such a change in the tax structure would be a significant departure from the current system and, despite the fact that it has been recommended as the most appropriate way of taxing inheritances and inter vivos transfers by numerous economic analyses, commissions and reports (e.g. Meade, 1978; Intergenerational Commission, 2018), does not appear to be presently under consideration, and so we do not consider it further here.

Relationship between inheritance tax and other taxes

Inheritance tax should not be seen as a replacement for other taxes, such as taxes on returns to wealth. Where taxes would apply when someone did not die, such as capital gains tax on increases in the price of assets or income tax on pension pots when drawn down, the occurrence of death should not lead to any relief from the paying of these taxes. Where this leads to two taxes being paid at the same point, sometimes described as ‘double taxation’, it is only making explicit the fact that (at least in some cases) inheritance tax will represent taxing assets that are taxable for some other reason apart from their transfer between individuals. The case for having an inheritance tax rests on being able to justify such double taxation (Summers, 2021). However, it is also worth noting that the two biggest asset classes in the UK – (main) homes and pensions – are exempt from taxes such as capital gains tax. Any special treatment of assets inherited would again give rise to equity and efficiency issues. Some may – unfairly – avoid these taxes, if they held their wealth in a form that was given special treatment. The potential to avoid tax at death may lead some assets to be held onto past the point where this would otherwise be of economic benefit to the holder or their heirs.

7.5. Problems with the current system of inheritance tax and taxation at death

In its current form, inheritance tax has a number of problems, each leading to different forms of unfairness and inefficiency. This section discusses these issues in some detail. Those interested in our recommendations and impacts of reforms may wish to proceed to Sections 7.6 and 7.7.

Many of the issues with inheritance tax relate to privileged treatment given to particular classes of assets: residential property, pensions, agricultural land, and businesses all have special treatment. The treatment given to lifetime gifts – important to consider in conjunction with the taxation of inheritances – also has problems, as does the treatment of gifts made to charities. In some ways the UK system of wealth transfer taxation shares some similar problems with other countries but in some ways it is unusual (see Box 7.1).

--------------------------------

Box 7.1. International experience of wealth transfer taxation

The design of inheritance, estate and gift taxes varies considerably across developed countries. In two key respects, the UK is unusual in how it structures inheritance tax.

First, while most advanced countries levy recipient-based inheritance taxes, the UK is one of just four OECD countries to levy taxes on estates passed on by donors (OECD, 2021). Recipient-based taxes allow for differential tax treatment based on the size of each recipient’s inheritance and other personal characteristics, and a majority of OECD countries use this flexibility to apply graduated inheritance tax rates. The UK is one of only seven to apply a flat rate above an exemption threshold (OECD, 2021).

Second, the UK is unusual in completely exempting all gifts from taxation, provided that they are made sufficiently far in advance of death. Other countries that treat inter vivos gifts differently from inheritances tend to implement tax-free thresholds, which may be renewed at intervals or applied at the lifetime level. The UK’s approach is also distinctive in that gifts must be made a relatively long time before death (seven years) in order to avoid being recharacterised as inheritances. Among OECD countries applying such restrictions, most choose periods from one to three years.

Figure 7.6. Revenue from inheritance, estate and gift taxation in OECD countries as a share of GDP, 2021

Source: https://stats.oecd.org.

In terms of how heavily inheritances are taxed, one can consider the tax-free threshold, rates schedule and, at a more macro level, the proportion of inheritances or estates taxed and the revenues from the inheritance tax as a share of GDP. Exemption thresholds vary dramatically, with some countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands, having exemptions in the low tens of thousands of euros. The UK’s exemption threshold puts the proportion of wealth transfers being taxed at the lower end by international experience, but its single tax rate of 40% is relatively high. Consequently, among OECD countries with taxation of inheritances, the UK is in the upper-middle of the pack in terms of revenues as a share of GDP (Figure 7.6). Revenues are substantially higher than in the US or Ireland, for example, but less than half as much as what is raised in Belgium, France and South Korea. Overall, in all advanced economies, revenues from wealth transfer taxes are quite small, at less than 1% of GDP.

A number of countries do not have an estate or inheritance tax and some advanced economies have abolished the tax in recent years. Austria, Portugal, Sweden and Norway all abolished their inheritance taxes within the last 20 years. Other countries have seen permanent or temporary reductions in the scope or rate of the tax (e.g. Italy and the US) or the introduction of substantial new reliefs (e.g. Germany).

Finally, one aspect that is common across most countries that have an inheritance tax is capital gains uplift being applied to assets at death.

--------------------------------

Treatment of property

The residence nil-rate band means that residential property wealth is treated distinctly from most other assets. In particular, as described above, there is an additional amount of wealth that is not taxed if an individual owns a residential property and they pass it on to a direct descendant. This residence nil-rate band can be claimed on at most one property that the deceased individual lived in at the time it was included in their estate.

This creates two obvious sources of unfairness. First, since it applies only to residential property, it disadvantages the small share of individuals who die with more than £325,000 in net assets but less than £175,000 in residential property assets. Given the huge variation in house prices across the country, the residence nil-rate band is effectively much less generous to those living outside London and the South East of England. As shown in Figure 7.7, 86% of individuals with over £500,000 in non-pension assets own property worth more than £175,000, but this varies from 95% in both London and the South East, to just 53% in Wales.

Second, since the residence nil-rate band only covers assets passed to direct descendants, those without children or grandchildren will have a larger amount of tax taken before the assets are passed to inheritors. This would apply a higher effective tax rate on assets someone chose to pass to their siblings, nephews and nieces, or friends, even where those individuals may already live in the property with them. Having a rich uncle or aunt is therefore less advantageous than having a rich parent.

Figure 7.7. Percentage of individuals across Great Britain in 2018–20 who, conditional on non-pension wealth over £500,000, have housing wealth of over £175,000, by region

Source: Wealth and Assets Survey round 7.

Together these restrictions mean that in 2020–21 almost 5,000 estates worth between £325,000 and £500,000 had to pay inheritance tax, making up 18% of all estates paying inheritance tax. It is hard to see the rationale for this special treatment of residential property passed to direct descendants. One might think that it relates to some special value of the family home. But there is no necessity for the residence passed on to be one that has been in the family for any amount of time. There is also no necessity for the inheritors to keep the property; as the HMRC guidance highlights, the lower tax rate applies even if the deceased’s will explicitly calls for the home to be sold and the cash from the home to be divided between his or her children. To prevent the tax benefits of homeownership encouraging people to stay in an unsuitably large home, there is downsizing relief, which allows the tax benefit to remain even where a property has been sold, highlighting the lack of connection between the tax break and transfer of the actual home itself. It also adds additional complexity into the tax system.

A sensible reform would therefore be to combine the nil-rate band and residential nil-rate band into a single tax-exempt amount which does not depend on what assets are held or who they are passed to. If there is a desire not to extend this higher nil-rate band to high-wealth individuals, a taper could remain in place removing 50p for every additional £1 of wealth between £2 million and £2.35 million.

Treatment of pensions

Defined contribution (DC) pensions are one of the lowest-taxed routes to making a bequest. On death, funds remaining in DC pension pots can be inherited by heirs but are not counted as part of the deceased’s estate. These funds therefore escape inheritance tax entirely. In combination with the introduction of the ‘pension freedoms’ reforms of 2015 – which removed the requirement to use accumulated DC funds to purchase an annuity – and the abolition at Budget 2023 of the charge on pensions exceeding the lifetime allowance of £1,073,100, this means DC pensions are a highly effective vehicle for passing on wealth to heirs in a tax-favoured fashion.

In addition, generally no income tax is levied on withdrawals from inherited pension pots if the giver dies below the age of 75. Income tax is, however, payable by the recipient if the pension is inherited from someone who died at 75 or older. Given that pension contributions are relieved of income taxation when made, this means that DC pensions bequeathed by those dying under age 75 escape income taxation at any point. Recent government documentation setting out the implementation of the lifetime allowance abolition suggests that this exemption will be curtailed for those taking withdrawals as regular income (HM Revenue and Customs, 2023b). We estimate that around £1 billion in pension pots will be bequeathed by those who die under age 75 without a surviving spouse in 2024–25. Assuming that these pension pots were spent over a period of several years, the amount of additional income tax generated by this reform would initially be in the tens of millions per year, but would grow over time.

As set out in detail in Adam et al. (2022), there is no good justification for this exceptionally generous tax treatment of pensions bequeathed. Sensible reform would bring pension pots into inheritance tax and apply income tax on all withdrawals from inherited pension pots. Adam et al. discussed some issues around how exactly this could be implemented. If inherited pensions face income tax on withdrawal, their inheritance tax treatment should recognise the fact that they are less valuable than the equivalent amount inherited in cash or other assets that do not attract income tax. Adam et al. proposed applying inheritance tax to 80% of the value of bequeathed pension pots (equivalent to applying inheritance tax to the value of the pension after basic-rate income tax has been deducted), or levying income tax at the point of death rather than withdrawal, in which case 100% of the post-income-tax value should be subject to inheritance tax. The latter reform would bring forward the levying of income tax to the point of death rather than subsequent withdrawal but it is primarily a re-timing of revenues so we do not estimate the income tax revenue effects of implementing one version of the reform versus the other.

The growing importance of DC wealth in households’ portfolios means that reforming the taxation of DC pension pots at death would have a growing impact over time. Undertaking reform sooner rather than later would therefore be wise. There is a particularly strong case for taking action as soon as possible if the government deemed it appropriate to phase in such a reform gradually (which could be done by gradually increasing the rate of inheritance tax according to the date of birth of the deceased).

Agricultural and business reliefs

Agricultural relief completely exempts from inheritance tax the value of all farms, after a minimum holding period. Land farmed ‘in hand’, i.e. by the owner, is exempted after two years. After seven years, it is exempted even if let out to someone else.

The latter criterion makes it clear that this exemption cannot be justified by reference to the protection of small family farms, since it does not require the benefiting estate to have ever actually farmed the land. The uncapped nature of this exemption also means it is poorly targeted if the intention is to protect small farms.

Business relief completely exempts from inheritance tax the value of interests in a business and of shares in an unlisted company, as long as the business is not merely a holding company for other investments. Business relief therefore covers both private businesses and partnerships where the deceased exercised control over the business, and shares of unlisted businesses where the deceased was merely an arm’s-length investor – for example, AIM shares.

Again, the rationale for the structure of this relief is difficult to understand: if the intention, as is sometimes suggested, is to protect small family firms, then it should not cover businesses owned at arm’s length. In fact, by value, around 80% of all business relief applies to shares in unlisted traded businesses (most notably AIM shares) where the deceased most likely did not exercise any control. If the focus is on small businesses, it would also seem natural to limit the total benefit from this relief to target small firms better.

More broadly, it is not clear that protection even for small farms or businesses is a sensible rationale at all. The existence of agricultural and business reliefs currently means an equivalent amount of revenue needs to be raised from some other source. By not taxing inheritors of these assets, potentially to make it easier for them to retain control of the assets, those who consequently face higher tax are less able to purchase or invest in these assets. It is also worth noting that the empirical evidence suggests that family-owned firms that have non-family management perform similarly to those with dispersed shareholders, and both perform better than businesses that are both owned and managed by a family (Bloom, Sadun and Van Reenen, 2010). From a productivity standpoint, there is therefore little case for trying to maintain family ownership.

One objection made to the taxation of agricultural land and of privately held businesses is that their value may be hard to ascertain, and hence they should be fully relieved. This is inconsistent with the fact that such assets have to be valued in many other contexts, such as on divorce or when there are shareholder disputes. The 100% relief applicable to these assets has also only existed since 1992, before which valuations were needed for inheritance tax purposes. Looking internationally, across the OECD only Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands have reliefs similar to agricultural relief. Other OECD countries that have reliefs like business relief also have far greater restrictions on when relief is available, and the conditions often require the business to be continued.

In 2020–21, 1,300 estates benefited from agricultural relief, relieving almost £800,000 of wealth from inheritance tax per claimant, on average, and reducing government revenues by £400 million. In the same year, 3,380 estates benefited from business relief, with an average of £950,000 in assets relieved and a loss of £730 million in revenues. These averages mask substantial variation, which we will see below means for businesses that much of the benefit goes to only a small number of recipients. Similar figures can be seen in previous tax years, so these numbers are not unusual despite the potential for higher deaths because of the pandemic. These figures also do not take into account lifetime giving, where use of agricultural or business relief may be substantial. For example, these reliefs can be used to avoid the 20% entry charge for gifts into trust, as well as not using up any of the nil-rate band were the giver to die within seven years.

Together these reliefs are estimated to cost £1.1 billion for transfers on death, or 20% of the total revenue raised by inheritance tax from deaths in 2020–21. This is a large sum and, as we show below, revenue from reforms to inheritance tax that restricted these reliefs could be used to substantially reduce the headline tax rate or increase the nil-rate band in a revenue-neutral way.

Charity exemption

Money left to a registered charity or club in a will is exempt from inheritance tax (as are gifts to political parties). Since 2012–13, if at least 10% of the value of the estate is left to registered charities, the headline tax rate applying to the remaining assets falls from 40% to 36%. Almost 10% of taxpaying estates make use of this 10% rule to reduce their tax rate, but these estates make up more than 95% of all gifts to charity on death (Office of Tax Simplification, 2019).

As with in-life charitable reliefs, these two measures provide a subsidy for charitable giving. In this case, these subsidies are targeted at those with estates over the inheritance tax threshold but it is unclear why this group should benefit from a higher subsidy for charitable giving than those with less wealth. If the government wishes to incentivise gifts to charities, it would be better to do this by offering a flat rate of matching of individuals’ donations. In the case of inheritance tax relief, the benefits accrue particularly to charities that older individuals support.

A further downside of the current structure for the tax break is that it disincentivises giving to charity in older age, as individuals with low incomes but high wealth will benefit more by delaying the gift until death, when their estate will benefit from the reduction in the inheritance tax rate.

In 2020–21, the exemption of charitable giving from inheritance tax meant a loss of £0.8 billion in revenue. The fiscal cost of the reduced inheritance tax rate on estates where 10% or more of the estate is donated to charity is relatively small. Around £50 million of tax revenue was lost in 2020–21 as a result of estates benefiting from a reduced tax rate due to charitable giving. On average, this is worth around £25,000 per estate that made use of the reduced rate.

Treatment of gifts

Overall, the annual flow of gifts is around 20% of the annual flow of inheritances (Boileau and Sturrock, 2023a). Gifts are currently tax-free if made seven years or more before death and count towards the estate and nil-rate band if given less than seven years before death. There are exemptions for some gifts even within this seven-year period. There is an ‘annual exemption’ for up to £3,000 in gifts, and other exemptions apply for gifts made for particular purposes (such as weddings) and regular gifts ‘out of income’. Gifts can be taxed more lightly than inheritances (given ‘taper relief’) if given between three and seven years before death; shorter than three years and they receive no relief. Gifts also count towards the nil-rate band in the order they were given. That means that an individual with £325,000 in nil-rate band needs to give over £325,000 in gifts in the period between seven and three years before their death before they begin getting this ‘taper relief’ on further gifts.

The complete exemption for gifts that are ‘normal expenditure out of income’ exists because forerunners to inheritance tax were concerned with the transfer of wealth rather than income. The distinction is a difficult one to maintain, because if income were saved rather than gifted, it would ultimately become part of wealth. Many of the gifts covered by this exemption are large: 45% of claims for this relief were for gifts exceeding £25,000 in 2015–16 (Office of Tax Simplification, 2019). If the rationale for inheritance tax relates to the transmission of resources across generations, gifts out of income should be treated no differently from any other gifts. We therefore recommend removal of this exemption. We acknowledge that implementation of this would require further work given that this exemption gives licence for some individuals to not have to track some frequent small purchases (e.g. spending on cohabiting non-spouses).

The form of taper relief may be considered odd. One might expect that a gradual reduction in the tax rate applied to gifts as they are further away from death would be designed so that the effect of a gift on inheritance tax liability gradually diminishes as that gift gets further from death. But under the current system, whether a gift up to £325,000 is made just after or just before seven years before death results in a change to the inheritance tax bill for a taxpaying estate by the full 40% of the gift amount. And gifts have this full effect for taxpaying estates regardless of when they are given within the seven years before death.

As a simple example, someone giving away £325,000 of cash to their child, and then leaving a further £325,000 in cash (and no other assets) on death would have £130,000 tax paid on their estate if their death were 6 years and 364 days after the gift: the gift uses up their nil-rate band, and 40% is payable on the remaining estate. This would also be true if the person had died just a day after the gift, or anywhere in between. But if they had instead died 7 years and 1 day after the gift, the gift would fall entirely out of the estate, and so their estate would pay nothing at all. If the government wanted a system where gifts are gradually less important for inheritance tax bills as they are made further from death, the proportion of the gift that is counted as part of the estate could be tapered down to zero, for example. But it is hard to see any rationale for the current set-up of taper relief. However gifts are taxed, we agree with the Office of Tax Simplification’s (2019) recommendation that taper relief be abolished.

Abolishing taper relief would mean an increase in inheritance tax paid by those making large amounts of gifts before death, which exceed their nil-rate band. Even among individuals covered by inheritance tax, those who have liquid assets large enough that they are able to give away more than £325,000 are unusually wealthy, making taper relief regressive.2 Other individuals would not see any increase in the tax paid by their estate if taper relief were abolished.

A wider question is how gifts prior to death should be taxed. One reason to tax them is to reduce the scope for ‘deathbed giving’: giving away assets shortly before death, to get them outside the taxable estate. The current seven-year look-back period is likely to be successful in preventing tax planning of this nature based on specific knowledge of mortality risk: there are few medical conditions where an individual will have more than seven years’ warning of death. However, advancing old age is clearly a predictor of mortality, and so much tax planning can be done as individuals age on the basis that their mortality risk is rising sharply. One response to this would be to increase the look-back period further: perhaps to doubling it to 14 years (it is currently already 14 in certain circumstances), or even much longer.

The core trade-off at the heart of this choice, given the current structure of inheritance tax, is between ideal design and administrative burden. It is not clear why gifts at any point should fall outside the scope of inheritance tax. There are two major problems with setting a fixed window where gifts are taxable. First, it creates unfortunate boundaries based on bad luck: for any fixed period where gifts are taxable, there will be cases where someone dies a few days before, and so their estate has to pay tax on the gift, while other similar individuals live a bit longer and so no inheritance tax is payable. Second, as set out in Section 7.3, there are substantial gifts given much earlier in life that are likely, for many individuals, to fall outside of even a 14-year period before death. To the extent that the rationale for inheritance tax is to reduce inequalities between individuals based on the wealth of their parents, and thereby enhance social mobility, the most significant gifts – such as those aimed at getting a child onto the housing ladder – may happen much earlier in life (see Box 7.2 for more detail). Without a very large increase in the look-back period for gifts, these are likely to continue to be outside the tax window for many people. The look-back period may even increase the perceived unfairness if it extends to a period that covers these major gifts for only some people, depending on how long they survive, both because of the randomness of who ends up paying and because less well-off individuals tend to die earlier and so are likely to have more of their gifts be taxable.

--------------------------------

Box 7.2. Gifts made during life

The annual flow of transfers made by living individuals is around one-fifth of the value of inheritances (Boileau and Sturrock, 2023a). Over a two-year period, around 5% of adults report receiving one or more gifts worth £500 or more. Less than 2% of individuals report receiving a loan from family (which may become a gift if not repaid). Most of these transfers are modest in size, with their median value being £2,000. But gifts are very unequally distributed, with the largest 10% of transfers being worth over £20,500. Gifts are most frequently received by people in their late 20s and early 30s, with 1 in 10 of that age-group receiving a gift over a two-year period, compared with rates of receipt of less than 5% for ages of 50 and older. Over four-fifths of the flow of gifts is from parents to their adult children.

It is likely that only a small proportion of these transfers would ever be liable for inheritance tax. Each individual can give away £3,000 per year without these transfers ever being counted as part of their estate. Furthermore, given that transfers are primarily received from parents and given when the child is in their 20s and 30s, it seems likely that in the vast majority of cases these transfers will be made further than seven years from the giver’s death. The number of estates reporting lifetime gifts within seven years of death and the value of these gifts, are small. The Office of Tax Simplification (2019) reported that in 2015–16, 4,860 estates included such gifts, with the total value of these gifts being £870 million. This compares with total net estates in that year being worth £79 billion, with 24,500 taxable estates.

--------------------------------

A potential solution to these boundaries is to instead include gifts over the entire lifetime. This has been implemented previously in the UK, and is the system currently used in the US. Between 1975 and 1986, under inheritance tax and its forerunner capital transfer tax, lifetime gifts were potentially taxable however long before death they were given. This raises a different set of issues, most notably around administration and record-keeping. Finding old records going back over a lifetime is unlikely to be feasible for an executor, and so non-compliance is likely to be high. This covers both inadvertent non-compliance, where old gifts are missed, and deliberate cases, where they are intentionally unreported because they will be hard to trace. The solution used in the US is to require contemporaneous declarations of large gifts (in excess of $16,000), which can later be tallied up on death. An objection may be that HMRC will have little incentive to focus compliance resource on these records at the time they should be made, since nothing is immediately taxable. This can be ameliorated by use of third-party reporting to automate checks where transfers go via bank accounts, along with prompts on large transfers to remind givers of their obligation to report. Higher penalties could now also be applied to the estate for incorrect declarations by the deceased if and when these are uncovered. Taxing lifetime gifts may also raise difficulties around determining what is considered to be a gift to, for example, minor children: the tax system and case law already draw boundaries here, but the pressure on defining and policing these boundaries may increase if such gifts could be used to remove assets from an estate.

A larger reform would be to go beyond extending the look-back period for gifts, and instead restructure the way in which gifts are taxed to largely tax them on an annual basis. Part of the difficulty with the present structure of inheritance tax is that it is ‘cumulative’ in nature: the amount of tax depends on the value of the full estate, including assets that left the estate in the years preceding death. This was particularly important historically, when there was a much larger range of tax rates, up to 85%. Without any contemporaneous tax liability (usually) attaching to gifts prior to death, there is little to incentivise accurate reporting in these years. If instead there were an annual gift tax, where tax liability depended on the amount given within-year (above some threshold), it would be clear that an administration and enforcement mechanism should be resourced. Gifts (and tax paid) in the final few years before death could be cumulated into the estate on death, as now, to prevent deathbed planning over this window, as is seen in other jurisdictions (OECD, 2021).

Whether or not such a tax is a good idea depends partly on what the goal of the tax is. Some will clearly feel that a regular tax on gifting is overly intrusive. On the other hand, an important period for the transmission of wealth between generations is likely to be when the younger generation in a family is in their 20s and 30s and making decisions on investing in education and housing (Davenport, Levell and Sturrock, 2021). This may therefore be perceived as a key time for policy to redistribute wealth transfers, with the aim of promoting social mobility. Inheritance tax as currently designed is unlikely to affect these transfers, creating the possible impetus for some approach to tax such gifts made earlier in life. However, the effects of such policies are not yet well understood.

We do not make any recommendations on the preferred structure for the taxation of gifts, although the status quo could clearly be improved upon. Design questions here are difficult, and the form of taxation would inevitably alter the types of gifts made. Evidence from the Netherlands, where there is an annual gifts tax, shows substantial bunching around the tax thresholds (Groot, Möhlmann and Sturrock, 2022). More work is needed on both the legal design aspects and the quantitative effects of reform before any particular design could be recommended.

Spouse exemption

By far the biggest relief in the inheritance tax system is spouse exemption: a complete exemption on transfers made between spouses or civil partners. In 2020–21, the total value of assets transferred under this exemption was £15.7 billion.

At a conceptual level, there are arguments for and against such an exemption. A possible justification is a desire to treat couples as a single economic unit for the purposes of wealth taxation, as happens in some other parts of the tax system, although more generally the UK has individual taxation. An exemption on the first death within a married (or civil partnered) couple ensures that tax does not create a necessity to sell the marital home, or create other major financial impacts on the survivor’s standard of living. It might also be claimed that transfers between spouses cannot have the same consequences for inequality of opportunity as transfers to the next generation. This is because the exemption is often assumed to be effectively a deferral of tax: when the surviving spouse (or civil partner) dies, the assets will then be taxed.

However, there is evidence that on the death of the first spouse, surviving partners increase their giving, particularly if they are a woman (Boileau and Sturrock, 2023b). These gifts may be made free of inheritance tax: small gifts, gifts relating to weddings and regular gifts are all free of inheritance tax. Where the surviving spouse lives more than seven years, any gifts, however large, are also tax-free; where the surviving spouse lives at least three years, there can be a reduced tax rate on those gifts.

For the very wealthiest, spouse exemption opens up a number of routes for reducing tax bills. For example, currently on death, the value of any capital gains is wiped out. Couples who have assets with large gains can therefore pass them between spouses on death free of inheritance tax and of capital gains tax. The assets can then be sold free of capital gains tax, and used to purchase AIM shares – covered by business relief – which will be free of inheritance tax when passed on, assuming the second spouse holds these at least two years before death.

Both of the above issues are indicative of wider problems in taxation at death, and could – and should – be tackled through modifications to the taxation of gifts and business assets and the removal of capital gains tax uplift (see Box 7.3). However, spouse exemption creates other issues which cannot be tackled anywhere else in the tax system. The core issue is that liability for inheritance tax depends on the domicile (permanent home) of the individual.3

--------------------------------

Box 7.3. Capital gains tax at death

Capital gains tax (CGT) is a tax on the increase in asset value for most assets other than the main home and assets held within an ISA or pension. Capital gains are taxed not when they arise, but at the point when the asset is sold. Since 1971, when someone dies, the accumulated (‘accrued’) gains are generally disregarded for tax purposes. The individual’s estate is not liable for CGT on the accrued gains, and the beneficiaries of the estate are deemed to acquire the asset at market value, meaning that when the asset is later sold, only gains from the date of death may be taxable.

The effect of this treatment is to incentivise individuals who have assets with large accrued gains to hold those assets until death, so that the tax that would otherwise be due is wiped out. This creates obvious inefficiency, since it encourages the holding of assets (e.g. a rental property or private business) even when they can no longer be managed well or are no longer the best investment, simply because of the tax advantage.

Forgiveness of CGT on death is also likely to be extremely regressive. Little information is available about gains on assets passed at death precisely because they are not taxable. However, gains realised in life are very concentrated among the wealthy, with 88% of all taxable capital gains going to individuals with more than £100,000 in gains (Advani, 2022). Over 70% of taxable gains come from unlisted businesses, which are skewed towards the very top of the distribution even among those who have taxable gains, and which can benefit from a lower CGT rate as well as exemption from inheritance tax (Advani and Summers, 2020). A reduction in the CGT relief for these assets in Budget 2020 will have increased the incentive to retain assets until death, by making the forgiveness more valuable.

The revenue consequences of CGT forgiveness at death are difficult to estimate because no data on these gains are available. Corlett, Advani and Summers (2020) used HMRC figures to estimate that in 2017–18, gains forgiven at death amounted to around £5 billion. Uprating this to 2021–22 in line with the growth of aggregate taxable gains implies that around £8 billion worth of gains were forgiven on death last year. Assuming these would all be taxed at 20% – the higher CGT rate for non-housing assets – this implies £1.6 billion in tax forgone. This number is similar to the estimate provided by the Office of Tax Simplification (2020) in its review of CGT.

One solution to these problems is to treat death as a disposal event. CGT can be applied as though the individual sold their assets just before death, and the CGT liability can then be passed to the estate to pay. Inheritance tax would then apply on the value of the net estate after the CGT was paid. This creates a consistent tax treatment between whether someone sells before they die or holds until death, so there is no reason for them to distort this choice for tax purposes. Unlike in the case where an asset is sold, there is not necessarily an increase in cash flow at the point when the asset is inherited. If the executor does not have access to savings to pay the CGT bill, they may therefore need to sell the asset. This is also largely true of gifts of assets during life.

Other solutions are sometimes proposed, such as inheriting the assets with the base cost (see Advani (2022) for a wider discussion of CGT reform issues). This means that when the asset is ultimately sold, CGT will then be due on the full value of the gain since the deceased purchased it. Like treating death as a disposal event, this means that capital gains do not escape tax at death. While this proposal sidesteps the issue of a potential lack of cash flow for the receiver, it has a number of problems. First, it leads to complex interactions between CGT and inheritance tax to ensure inheritance tax is not paid on the part of the accrued gain that will be paid in tax. Second, it has the administrative difficulty of requiring the inheritor to, potentially many years later, have records of what the base cost was. Third, there is more scope for avoidance – for example, by the inheritor of a very large gain leaving the UK for a few years to receive the gain free of CGT. Fourth, given the frequency with which CGT has been reformed in the past 40 years, there would also be an incentive to hold onto the asset until some more favourable reform takes place.

One objection sometimes made to the abolition of forgiveness at death is that both CGT and inheritance tax are then payable at the same time. This is both correct and intentional. CGT and inheritance tax are serving different purposes. CGT taxes the increase in value of assets, and for administrative convenience is only payable when there is a transaction: at this point the asset needs to be valued anyway, and on a sale the seller has cash with which to pay the tax. Inheritance tax taxes the transfer of assets between individuals at death, or in the seven years before. On death, if an asset has accrued gains, it is appropriate to tax these just as much as it would be if the asset were sold the day before death, where it is currently being taxed. A valuation for the asset is anyway needed at this point, and any future recipient of the asset can either sell it to pay the tax, or can borrow or dip into savings if they want to retain the full value of the asset where it is indivisible.

--------------------------------

There is no obvious way to define potential liability for inheritance tax based on how a couple is connected to the UK, particularly since an individual may end up married or civil partnered to more than one person over the course of a lifetime. This creates problems where, for example, one member of a couple dies, and the other later leaves the UK and settles abroad. Spouse exemption means no tax is paid on the first death, and if the survivor makes a permanent home elsewhere, they will generally not pay UK inheritance tax. A related problem can arise where members of a couple have different domiciles. For example, in the case of a couple where the husband is UK-domiciled and wife has a domicile in Switzerland, if the husband dies first and leaves all assets to his wife, they can then fall outside the scope of UK inheritance tax.4 These concerns are not merely theoretical. Foreign-born individuals are very prevalent at the top of the UK income and wealth distributions (Advani et al., 2022; Advani et al., 2023).

To tackle this, and other ways in which spouse exemption can lead to assets being removed from the UK inheritance tax base, one option would be to entirely remove spouse exemption. This would revert us to the structure of estate taxation before 1972, when the exemption was first introduced. However, the reason for its introduction was the concern that, otherwise, the surviving spouse might have their entire lifestyle change upon the death of the first spouse, and this concern remains. While tax always affects the choices that are available, many would see it as an unreasonable outcome for the death of a spouse or civil partner to create major financial hardships. A second concern might be that the assets may be taxed on the death of both members of the couple. It is worth noting that both of these issues are currently experienced by unmarried cohabitees (including siblings, for whom marriage / civil partnership is not an option).

One possible solution to ensuring the surviving spouse does not face hardship caused by the inheritance tax due would be to retain spouse exemption, but set a very high cap on the total value of assets that could be covered by it. This is the approach taken by most countries that have an equivalent to spouse exemption. The intention would be to set this at something sufficiently large that it clearly does not create hardship for the surviving spouse, but which still ensures some of the tax is collected on the first death in the case of extremely wealthy couples. A cap of £2.5 million, for example, would affect less than 1% of couples. Existing provisions already mean that, where estates have liquidity issues in paying the inheritance tax – for example, where the only asset is a house – the tax can be paid in instalments over 10 years (Loutzenhiser and Mann, 2021); this would continue to apply.

Merely introducing a cap on spouse exemption would mean that, in some circumstances, the same assets are subject to inheritance tax twice: assets in excess of the cap would be taxed on the first death, and then again on the second death, assuming the survivor lived long enough that quick succession relief did not (fully) apply. Whether or not this double inheritance taxation is a good thing will be a matter of individual judgement. Some might find it unreasonable for the same assets to be taxed again, even where the survivor had many years of benefit from the assets. Others might consider this a useful increase in the progressivity of inheritance tax: in the absence of other reliefs or tax planning, the assets in excess of the threshold would be taxed twice, making an effective rate of 64%, although if a more progressive rate is the aim then it could be achieved more simply by introducing higher tax bands directly. An objection to having some assets taxed on both deaths is that it would in practice probably lead to assets in excess of the cap being left to children / other beneficiaries, to prevent them being taxed on the death of the survivor. Wealthy individuals taking tax advice will likely be offered a trust structure that allows the survivor to retain benefits without having ownership, to prevent taxation on the second death. Those with less access to planning advice, and the public at large, will legitimately be unhappy that the system does not work as apparently intended for those who are very wealthy.

One attractive option that would remove the ‘double tax’ without requiring individuals to engage in complex planning would be to introduce a cap on spouse exemption, but combine this with a rise in the survivor’s nil-rate band. The appropriate increase would be the amount of post-tax assets in excess of the cap. For example, suppose the cap were set at £2.5 million. A wife dies with an estate worth £3.5 million, leaving everything to her husband, and her nil-rate band was fully used by an earlier gift (and no other reliefs apply). The husband gets spouse exemption on the first £2.5 million, and then 40% tax is applied to the remaining £1 million, so that he gets a further £600,000. To ensure the assets in excess of the cap are not taxed on his death, he would also get an effective increase in his nil-rate band of £600,000. This addition would only apply on death – i.e. not to gifts – to ensure other potential avoidance opportunities are not created. The effect of this is that the inheritance tax paid on the first death is effectively a prepayment in most circumstances: if the husband’s estate is subject to UK inheritance tax when he dies, it will have tax relief on the value of these assets. If for some reason his estate is not subject to inheritance tax, then this reform ensures tax is paid that otherwise would not have been.

The inheritance tax treatment of couples needs to strike a balance between allowing for the sharing of assets between couples (ideally both married / civil partnered and cohabitees) and the individual-specific conditions for one’s estate being liable for inheritance tax. Anecdotally, spouse exemption is used by some in ways which ultimately fully avoid, rather than merely defer, inheritance tax. However, existing data sets do not provide any way to measure this quantitatively. In the absence of data on these issues, it is difficult to make any firm recommendations on whether and how reform should be done, but this is clearly an area where further investigation is needed.

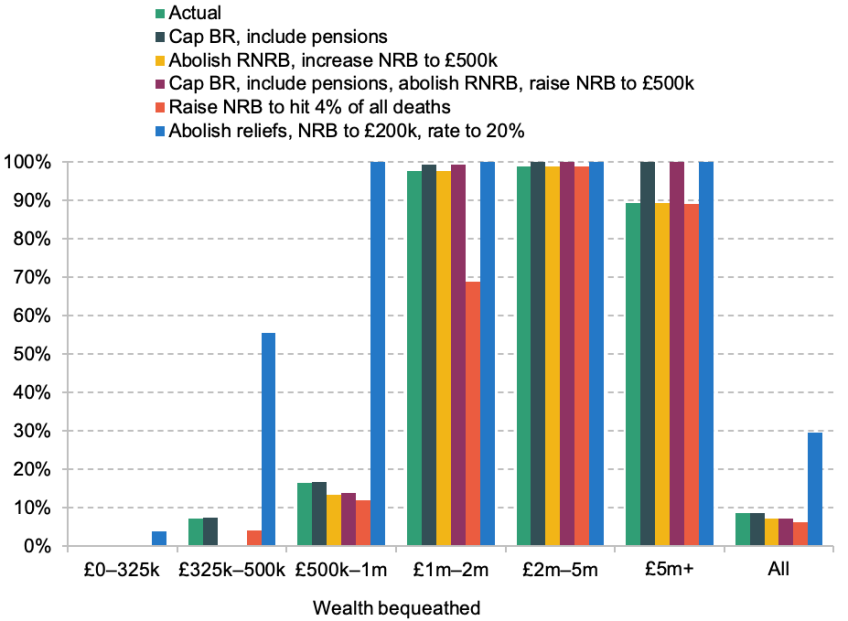

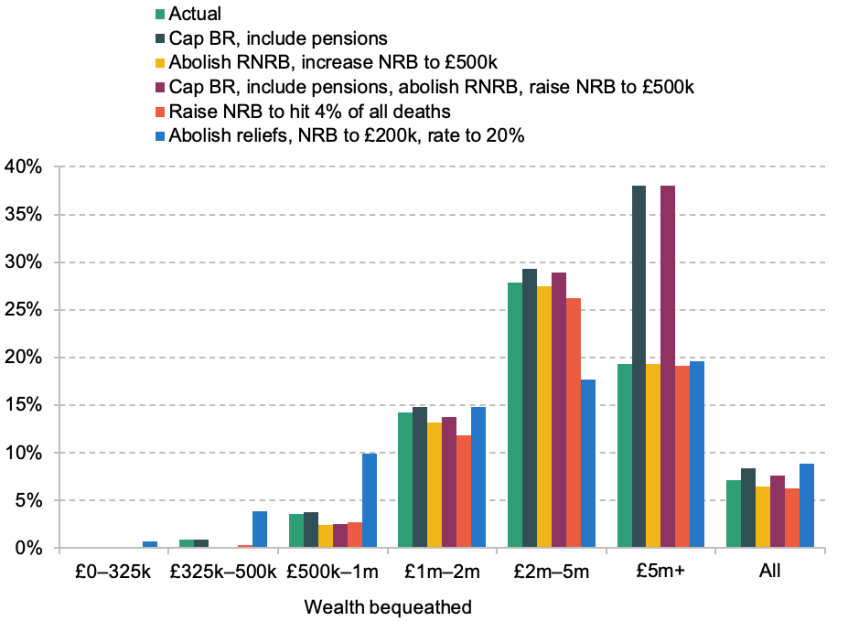

Implications