Spring heralds the arrival of new tax regimes. While the Chancellor’s Budget did not in the end contain any cuts to the headline rate of inheritance tax, it did introduce a new inheritance tax relief. From April next year, agricultural relief will be extended to include ‘environmental land management’. As a result, landowners will be able to pass on any amount of ‘agricultural land’ tax-free, even in some cases where it is not being used for agriculture.

The expansion of this relief is so small as to be fiscally almost irrelevant: HMRC says it will cost only £5 million per annum by 2028–29, while agricultural relief already exempts around £400 million of tax on agricultural land passed on at death each year. Nevertheless, it illustrates a key economic and political problem with an inheritance tax system that gives special treatment to some assets. If rural land can be passed on free of inheritance tax when farmed, but not when used for conservation purposes, it clearly disincentivises the latter. This creates understandable pressure for a tax break, leading to a new carve-out and reduction in revenues. The fundamental problem here is that once a relief is created, there are always arguments for expanding its scope to avoid some unfairness at the margin. The root of the problem is the creation of the special relief in the first place.

Inheritance tax is littered with special exemptions. In the past tax year (2023–24), the tax raised around £7 billion from the 5% of deaths that generated a tax bill. Reliefs for business assets, agricultural property and gifts to charities meant forgoing a further £2.4 billion in revenues.1 The residence nil rate band, which allows £175,000 of the value of a home to be passed to direct descendants (on top of the standard £325,000 that everyone can pass on tax-free), adds another £1.8 billion, bringing the total cost of these reliefs to around £4.2 billion. The total exemption of defined contribution pension pots has a cost in the low hundreds of millions now, but this is set to grow fast. On top of these major carve-outs, there are a plethora of smaller reliefs. The total number is difficult to even count, with the Office of Tax Simplification reporting 88 reliefs a decade ago!

These reliefs are most heavily used by the biggest estates. As a result, despite a headline tax rate of 40%, the effective rate of inheritance tax paid peaks at 25% for estates worth between £3 million and £7.5 million, before declining to just 17% on estates worth £10 million or more (see Figure 1).

These reliefs and exemptions are unfair, have substantial revenue costs, and inappropriately distort economic choices. The government could make inroads to improving the system in three ways.

1. Remove special treatment of AIM shares

The AIM (formerly called the Alternative Investment Market) is the London Stock Exchange’s market for small and medium-sized growth companies. Since 1996, shares listed on the AIM that have been held for at least two years before death get a 100% relief from inheritance tax as part of business relief. This distorts investment choices towards these types of shares, particularly for older people seeking to minimise their inheritance tax liability. There is no rationale for this relief based on supporting family businesses as AIM shares are held at arm’s length in a similar way to regular shares.

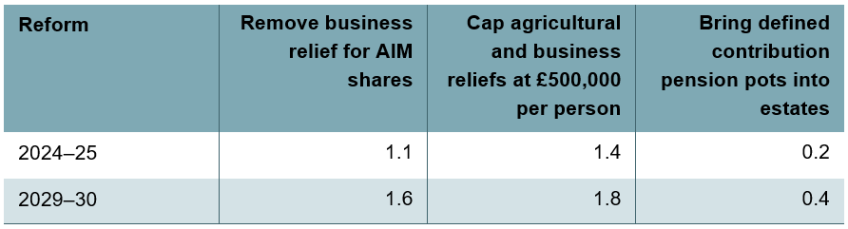

Revenue implications: We estimate that the removal of business relief for AIM shares could raise around £1.1 billion in the current tax year, rising to £1.6 billion in 2029–30. This could be an underestimate, since business relief on AIM shares is used very heavily by trusts, for which no direct statistics are available. If those currently using AIM shares to avoid inheritance tax would respond to its removal by using other avoidance strategies, the amounts raised could be lower, though.

2. Cap agricultural and business reliefs

There is a strong economic case for completely abolishing agricultural and business reliefs (with the latter including the relief for AIM shares), which currently cost around £400 million and £1.4 billion a year, respectively. That said, there is likely to be strong pressure on politicians not to make a change that would raise taxes for those passing on family farms and businesses. One option would be to cap the amount of business and agricultural relief at £500,000 per person, with the unused portion of the allowance being transferable to a surviving spouse or civil partner. This would mean that a couple could pass on a farm or business worth £1 million. Because the vast majority of business relief is claimed by the largest estates – we estimate that 90% of business assets are passed on as part of estates worth over £2 million – such a cap would also capture most of the revenue gains that could be achieved by abolition.

Revenue implications: We estimate that capping agricultural and business relief at £500,000 per person would raise £1.4 billion in the current tax year, rising to £1.8 billion in 2029–30. Again, this could be an underestimate, since agricultural and business reliefs are used very heavily by trusts, but could be an overestimate if removal led to greater use of other avoidance strategies. Choosing a higher level of cap would lead to lower revenue gains.

3. End the tax-free passing-on of pension pots

Defined contribution pension pots can be passed on inheritance-tax-free. Those with sufficient other wealth to fund their retirement and who want to pass on some wealth when they die are therefore strongly encouraged (by the tax system and as a result their financial advisers) to use their pension as an inheritance tax avoidance vehicle. This exemption serves no economic purpose and is clearly unfair. Pension pots should be brought into the scope of inheritance tax (with an allowance for the fact that income tax may be paid on the income withdrawn from them – see Adam et al. (2022) for further discussion).

Revenue implications: Including the value of defined contribution pension pots in estates would raise around £200 million in the present tax year, rising to around £400 million in 2029–30. Because defined contribution pension pots are becoming more prevalent and larger in size over time, the revenue gain from bringing them into the scope of inheritance tax is set to rise, reaching up to £1–2 billion (in today’s terms) in the coming decades.

Table 1. Revenues raised from reforms to inheritance tax reliefs

Note: Business relief includes relief for AIM shares. As a result, revenues raised from removal of business relief for AIM shares and from capping agricultural and business reliefs are not additive.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Bringing pension pots into estates and either removing AIM from business relief or capping agricultural and business reliefs would raise upwards of £2 billion in 2029–30. This is substantial revenue, similar in scale to the amount of money that the government has proposed to raise by scrapping the non-dom regime or about a third of the size of increasing the main National Insurance contributions rate by 1 percentage point. Such changes would reduce the inequity seen in effective tax rates. If desired, these additional revenues could be used to increase the nil-rate band for inheritance tax or to cut the headline rate to around 33%, leaving the overall amount raised from inheritance tax unchanged. Alternatively, the revenues could be used for other tax or spending priorities or to reduce borrowing. Reducing reliefs for business assets or agricultural land would also mean that investment was made into the most productive projects rather than those that are tax-favoured, which is a positive for economic growth. Existing reliefs encourage inefficient investment, distorting economic decision-making. This is precisely why there were calls to expand agricultural relief to land management: because tax drives choices.