Executive summary

‘Non-doms’ – people who live in the UK but who are not settled here permanently– currently enjoy certain tax advantages. The Labour Party has said that it intends to ‘scrap the non-dom rules, bringing in a modern scheme for people who are genuinely living in the UK for short periods’1 if it wins the upcoming general election. Recent reports suggest that the Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, is now considering reforming the taxation of non-doms in this week’s Budget.

There is a strong case for reform. The subjective concept of domicile is an unsatisfactory basis for taxation; it would be better to base taxation on objective, observable criteria such as years of residence. And there are undoubtedly inequities and anomalies in the current system: for example, it actively discourages wealthy non-doms from bringing their wealth into the UK. But there is also a strong case, both principled and pragmatic, for not applying all UK taxes in full as soon as people arrive in the UK. There is a range of possible reform options; careful consideration of the appropriate design of the system is needed.

The taxation of non-doms is a complex area and has been reformed significantly in the past 20 years. Here we summarise what is known (and not known) about non-doms and the key policy issues involved with ‘scrapping’ or reforming their current tax regime.

Key facts and unknowns

1. There are around 37,000 non-doms in the UK who opt to be taxed on a ‘remittance basis’, meaning that UK taxes are not charged on their foreign income or capital gains unless they are remitted to the UK.

2. Those 37,000 people collectively paid about £6 billion in UK income tax, National Insurance contributions and capital gains tax in 2020–21 – an average of around £170,000 each.

3. Reforms in the past 20 years have imposed charges for claiming the remittance basis and restricted who can claim it. Notably, since 2017, the remittance basis is available for a maximum of 15 years, rather than indefinitely. Some non-doms continue to benefit from some other tax advantages beyond 15 years.

4. It is not possible to directly measure how much foreign income non-doms using the remittance basis have (and therefore what the potential tax base is). And there is only limited evidence on how non-doms would respond to higher taxes.

5. The exact design of any reform, including how it applied to trusts, could have a major effect on how non-doms would respond and how much revenue would be raised.

6. One important choice is how to treat people who have been in the UK for only a short period. A number of countries have special regimes for recent arrivals. Roughly half of the total offshore income and gains of non-doms is estimated to relate to people who arrived in the UK in the past five years. This group is likely to be more responsive to taxes than people who have lived in the UK for longer.

7. One (and the only publicly available) estimate suggests that taxing all foreign income and capital gains of non-doms in the same way as UK doms after they have lived in the UK for five years could increase revenues by around £1.8 billion. There is substantial uncertainty around this, with the risks probably skewed to the downside.

8. More ambitious tax-raising reforms mean a higher potential revenue yield, but also increase the risk of counterproductive behavioural responses, most notably including non-doms leaving the UK (or not coming in the first place).

9. Revenue should not, however, be the sole criterion for assessing the merits of reforms. And short-term revenue needs should not drive hasty decisions on a complex policy issue where finding a system that can be stable for the long term is important.

Who are non-doms and how are they taxed?

Foreign domiciliaries, or ‘non-doms’, are people who live in the UK but are not settled here permanently. A typical non-dom is a foreigner who comes to work in the UK for a few years and then returns. But some were born here, and effectively inherited non-dom status from their father (or mother if she was unmarried at the time of the birth and remains unmarried while the child is a minor). And some non-doms have lived in the UK for many years, although tax advantages are now significantly reduced after 15 years.

Non-doms are taxed in full on their UK income and capital gains. But unlike other UK residents, they can choose to be taxed on the ‘remittance basis’, meaning that they are not taxed on their foreign income and capital gains unless they bring the proceeds into the UK2 . If they are not tax-resident in another country, then they will often pay no tax in the country in which the income arises either3 . Non-doms who have lived in the UK for seven years must pay a £30,000 annual charge to claim the remittance basis, rising to £60,000 after 12 years4 . The charge was introduced by the then Labour government in 2008 and there have been various changes to the regime since 2010. Most recently, in 2017, the regime was changed so that UK residents who were either born in the UK to a UK-domiciled father (or mother if unmarried) or have lived in the UK for at least 15 of the past 20 years are ‘deemed domiciled’, meaning they are taxed broadly as if they were domiciled in the UK5 . People who live in the UK can therefore no longer claim the remittance basis indefinitely.

Non-doms get other tax advantages, even if they do not claim the remittance basis. These include:

- Favourable treatment for inheritance tax. Assets held abroad – including UK assets (other than housing) held through an offshore company – are not subject to inheritance tax if the deceased was not domiciled (and not deemed domiciled) in the UK at the date of death6 .

- Favourable treatment of non-resident trusts. A UK domiciliary normally faces an inheritance tax charge when they put assets into a non-resident trust, and pays capital gains tax (CGT) on any rise in value when the assets are sold; those who are not UK-domiciled (and not deemed domiciled) do not have to pay either of those taxes. A non-dom who was born outside the UK and puts non-UK assets into a trust before they have been UK-resident for 15 years can permanently shelter such assets from inheritance tax not only for themselves but also for future generations7 .

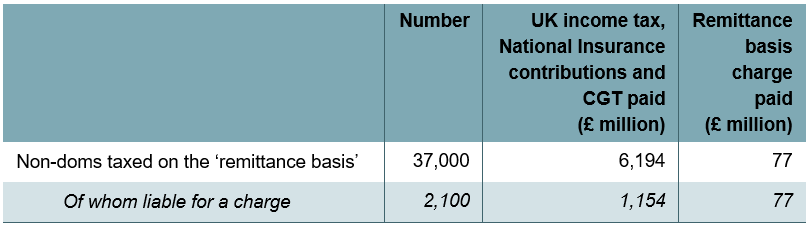

Table 1 shows that in 2020–21 there were 37,000 non-doms claiming the remittance basis for tax purposes, of whom 2,100 had been in the UK for at least seven years and therefore had to pay a charge to claim the remittance basis.

Table 1. Number of non-doms and tax paid, 2020–21

Note: £77 million is the amount paid through the remittance basis charge. It is not the revenue yield from the existence of the charge, since the existence of the charge affects revenue from other taxes too: some people opt to pay tax on their worldwide income and capital gains to avoid the charge, while others decide not to live in the UK at all.

Source: HMRC (July 2023) ‘Non-domiciled taxpayers in the UK’, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/statistics-on-non-domiciled-taxpayers-in-the-uk.

Non-doms claiming the remittance basis tend to have high UK incomes, a large share of which comes from employment (Advani, Burgherr and Summers, 2023). In total, non-doms claiming the remittance basis paid a little over £6 billion in UK income tax, National Insurance contributions and capital gains tax – an average of about £170,000 each. The remittance basis charge directly raised £77 million from the 2,100 people who paid it8 .

Considerations when taxing non-doms

As a matter of principle, it seems hard to justify taxing non-doms who have lived in the UK for many years more lightly than other UK citizens. Doing this creates a clear unfairness. But if all new arrivals were immediately taxed in the same way as UK doms, it would raise principled issues of fairness for this group. For example, would it be fair to levy UK inheritance tax on a person’s worldwide estate if they die six months after arriving in the UK? And would it be fair to tax capital gains that accrued before someone came to the UK just because an asset was sold while a person lived here?

Alongside questions of fairness are questions about how non-doms would respond to higher taxes. Increasing tax on non-doms towards or to align with that of UK doms would remove a significant incentive for some foreigners to be in the UK. The non-doms who would be most responsive to higher taxes are likely those who have only recently – or not yet – moved to the UK, because it is presumably easier for them to choose to live elsewhere. The details of the regime may also affect other decisions such as where they invest, the use of trusts, and so on.

As a result of these issues, a number of countries have tax rules that distinguish between what are in effect permanent residents and people who have recently moved from another country. UK reforms have moved in this direction. But there is not a single ‘right answer’ to the question ‘How long should a person have to live in the UK before we start subjecting them to UK taxes in full?’. And the answer may well be different for different taxes. In practice, other countries take a variety of different approaches.

Policy choices will affect which types of people come to a country. The UK’s current regime is relatively attractive to non-doms with high (offshore) wealth, although not necessarily to those who want to invest that wealth in the UK (because remitting money to the UK brings it within UK taxes). Some other countries, including France, Italy and Spain, have regimes that are aimed at attracting workers and do this by placing lower taxes on employment income for a period after arrival.

There are inevitably debates about which types of people the UK should look to attract – or at least not deter. There could potentially be benefits (or costs) to the rest of society from having non-doms in the UK, over and above their net contribution to the exchequer (i.e. the total tax they pay minus the cost of the services they use). Employing people and buying goods and services in the UK do not, in themselves, normally constitute benefits to wider society, since those resources could otherwise be put to alternative uses; the fact that non-doms earn and spend a lot of money in the UK is not, in itself, a good reason to want more non-doms. But if non-doms are unusually entrepreneurial then there could be some positive spillovers to the productivity of other UK businesses. Some would argue that the presence of a super-rich and socially segregated non-dom elite detracts from the cohesion of British society; others might argue that non-doms bring welcome diversity and vibrancy to British society. It is impossible to quantify these costs and benefits reliably. But they are factors that should be considered in making policy decisions.

Options for reform

The Labour Party has said that it would ‘scrap the non-dom rules, bringing in a modern scheme for people who are genuinely living in the UK for short periods’. It has also been reportedrecently that the current Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, is considering scrapping or scaling back the current tax breaks for non-doms in this week’s Budget. But this leaves open the question of exactly what either party would do: how they would reform the current regime or what they would replace it with. There is a range of options and issues to consider.

Modest reform options include shortening from 15 years the period for which people can be UK-resident before they are deemed domiciled in the UK, requiring them to pay a charge for the remittance basis after less than the current seven years, or increasing the level of the charge.

The regime could also be changed more fundamentally. One interpretation of ‘scrap the non-dom rules’ is that domicile would no longer be used as a basis for taxation. This would be a welcome change. Domicile is a problematic concept that is based on nebulous, subjective and difficult-to-prove criteria such as where one intends to reside permanently9 . It would be better to base taxation on objective, observable criteria such as years of residence. Since 2013, the UK has operated a statutory residence test which clearly determines whether a person is tax-resident in the UK in any given year10 . Using this as a basis for taxing non-doms would simplify administration and create fewer disputes. If domicile is removed as the basis for taxation, a key policy question will be what, precisely, replaces it: should years of residence be the only factor determining applicability of UK taxes or, if not, what else should be taken into account? For example, citizenship, whether a person is foreign-born and/or the location of an estate’s beneficiaries could be taken into account when determining the applicability of UK taxes.

The current regime has some clear inequities and distortions. Among other things, it penalises non-doms for bringing their wealth into the UK and it encourages them to move assets into trusts (and/or crystallise capital gains and income) before reaching 15 years of residence and being deemed domiciled here.

Nevertheless, as discussed above, there are both principled and practical arguments for not simply taxing all UK residents in full on their income, capital gains and bequests from the moment they arrive in the UK until the moment they leave. The Labour Party has indicated that it would put in place a favourable regime of some sort for people ‘living in the UK for short periods’, and that it would consult on precisely what that should look like. In setting out any such regime for people in the UK for a short period, there are two broad questions that would need to be answered11 . The answers are likely to differ for income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax.

First, what tax advantages would recent arrivals get? A new regime could mimic the current regime in that income earned in the UK was taxed here in full, while offshore income and gains were not taxed for a set number of years (unless they were brought into the UK), perhaps subject to a charge to access this treatment. Inheritance tax could continue to be limited to assets held in the UK (and UK housing held via an offshore company). But as noted above, there are inequities and perverse incentives in the current system: it should be possible to do better. In principle, a new regime could:

- apply preferential treatment to foreign income and gains irrespective of whether they are brought into the UK;

- remove (partly or entirely) preferential treatment for foreign income, but retain preferential treatment of foreign capital gains and/or estates;

- ‘rebase’ assets for CGT purposes at the point a person moves to the UK (like Canada does), so that only the rise in value that occurs after they arrive is taxed (conversely, the UK could tax capital gains realised within a certain period after a person leaves the UK, at least on the estimated part of the rise in value that accrued before they left; or levy CGT when they leave on gains accrued by then, perhaps with the option to defer payment and cancel it if the person returns);

- exempt (all or part of) estates from inheritance tax for a period after someone arrives (conversely, the UK could – and already does – tax estates for a period after a person leaves the UK);

- give preferential treatment (e.g. a lower tax rate) to income earned in the UK for a period after a person first moves to the UK.

This gives a flavour of the choices entailed in establishing a regime for people who move to the UK, but it is not an exhaustive list of policy options. Whatever approach was chosen, there would be important questions about how trusts (and other vehicles) should be treated, for example. Wrapped up in the options are questions about who it is we want to attract to the UK (or at least not deter from coming) – do we want to attract specifically people who have large amounts of offshore wealth that they would not bring to the UK, as the current regime does, rather than (say) those who would invest in the UK or produce and earn a lot in the UK?

Second, how long should preferential treatment last and how should it be withdrawn? Tax advantages for new arrivals could be removed sharply after a certain number of years of residence or be phased out gradually over a number of years. Different choices could be made for different taxes. To give just one specific example as an illustration, offshore income could be exempt from UK tax for the first, say, four years after a person moves to the UK (and then be taxed in full), while the proportion of a person’s estate that is subject to UK inheritance tax could be zero for the first four years and then be increased from 0% to 100% over the following, say, 10 years.

With any reform, a decision would be needed on whether any new regime would apply in full immediately or whether there would be any ‘grandfathering’, transitional provisions or advance notice of reforms, to protect existing arrangements or give people time to rearrange their affairs without incurring a new tax liability12 . Again, this is not an exhaustive list of policy questions, but illustrates that there is a range of important and complex issues that would need to be addressed.

The precise design of any policy and how it is introduced would have an important impact on how current (and potential) non-doms would respond and how much revenue could be raised (or lost) from reforms.

Potential revenue

In recent years, more data on non-doms have been made available. More is therefore known about this group than in the past. But there are still no data on the foreign assets or incomes of non-doms using the remittance basis, who do not have to declare them. And we have only limited evidence that can inform how non-doms might respond to potential future reforms. Here we set out what is known and what the main unknowns are. The main conclusion is that, even if we knew the exact policy that a government planned to enact, there is a great deal of uncertainty around both how much foreign income non-doms have and how they would respond to any new regime. There is therefore significant uncertainty about how much revenue could be raised.

Advani, Burgherr and Summers (2022a) use anonymised data from HMRC tax records to estimate how much foreign income and capital gains non-doms have, based on the investment income of comparable UK doms. They estimate that taxing non-doms’ foreign income and gains like the income and gains of UK doms would raise £3.6 billion a year if non-doms took similar steps to UK doms to mitigate tax liability on their investment income13 . In reality, non-doms could have more or less income from offshore assets than estimated – the potential tax base could be larger or smaller – but the approach used is reasonable (and produces the only estimate available). However, in addition to uncertainty about the size of the potential tax base, there are reasons to believe that non-doms would do more to mitigate their tax liabilities than UK doms.

Most obviously, they might leave the UK – or the next generation might not come here in the first place. To the extent that happened, the exchequer would not only forgo the additional revenue from higher taxes but also lose the UK tax non-doms do currently pay, such as that shown in Table 1 (and others such as VAT), which typically far exceed the cost of the public services they use. Advani, Burgherr and Summers (2023) study what happened after the 2017 reform when those who had been in the UK for more than 15 years were deemed domiciled here and therefore had to pay more tax. They find a very low migration response; hardly any non-doms left the UK in response to the reform14 . This is compelling evidence on the initial effects of the specific 2017 reform on outward migration (though it is possible that more non-doms left later). But this low migration response relates to non-doms who had already lived in the UK for 15 years. Those who have been here for a shorter period – or those who would consider coming here but have not yet done so – could be more likely to leave the UK (or not come) in response to higher taxes, which in turn would reduce how much revenue could be raised.

Furthermore, one reason those deemed domiciled in 2017 did not leave the UK in response might be that the government did not really try to tax them like UK doms: it deliberately left a way to sidestep the tax, by allowing non-doms (except those who were UK doms at birth) to move their offshore assets into trusts before they were deemed domiciled and allowing some income and gains from those offshore trusts to continue to be tax-free provided the non-dom did not bring them into the UK or add anything more to the trusts after becoming deemed domiciled. This made it possible for many non-doms to continue to protect their foreign income and gains from UK tax without needing to leave immediately15 .

Non-doms may also have other ways to escape paying UK tax that are not as easily available to UK doms. For example, they could transfer ownership of the assets to a family member overseas, or seek to (illegally) evade taxes by simply not reporting their overseas income (although countries are now sharing more information to make this harder).

Of course, how much revenue would be raised from a reform in practice would hinge critically on precisely how the current regime was changed. It seems unlikely that the current regime is raising the maximum possible revenue from non-doms: it is very likely that modest reforms could raise a little more revenue. More ambitious tax-raising reforms increase the potential revenue yield, but also increase the risk of counterproductive behavioural responses. For example:

- If something akin to the remittance basis is kept for recent arrivals, the potential yield would fall substantially: Advani, Burgherr and Summers (2022a) estimated that roughly half of the total offshore income and gains of remittance basis users was associated with people who had arrived in the UK in the past five years. But recent arrivals are probably the more mobile group of non-doms. As such, getting £1.8 billion (i.e. half of £3.6 billion) from restricting the remittance basis to those within five years of coming to the UK is more likely than getting £3.6 billion from abolishing the remittance basis completely.

- If a future reform kept protections for non-resident trusts, it would be easier for non-doms to sidestep the tax, reducing the amount of tax paid by those who remain in the UK but also reducing the number who choose to leave (or not come to) the UK.

- If, as well as increasing tax on foreign income and gains, a reform included removing or restricting inheritance tax advantages, there would be an increase in the potential tax base, but also an increased incentive for non-doms to leave (or not enter) the UK16 .

Reforms that were more fundamental than simply withdrawing existing tax advantages from some or all non-doms might have entirely different revenue implications. For example, moving towards favourable treatment of UK rather than offshore income could see very different responses from different types of non-doms.

The upshot is that it might be possible to raise a couple of billion pounds from restricting the preferential treatment of foreign income and gains to the first five years of residence, but there is substantial uncertainty around this. The upside risk is that non-doms have more foreign income and gains than estimated. The downside risks are that foreign income and gains are smaller than estimated and/or that non-doms respond more than UK doms to having their investment income taxed. Our judgement is that the downside risks are probably larger. More broadly, the revenue yield of any reform to the taxation of non-doms would hinge critically on the details. The more ambitious tax-raising reforms are, the greater the potential revenue yield – but also the greater the risk of counterproductive behavioural responses, most notably non-doms’ leaving (or not coming to) the UK. Revenue, however, should not be the sole criterion for assessing the merits of reforms: as discussed above, there is a range of principled and practical arguments to consider.

Conclusions

The taxation of non-doms is a complex area, both in principle and in practice. On fairness grounds alone, there are arguments for taxing non-doms who have lived in the UK for many years in the same way as UK doms, but also arguments for not applying all UK taxes in full as soon as people arrive here. Lower taxes for recent arrivals could also be justified on the basis that they are likely to be more responsive to taxes. While it would be possible therefore to scrap the non-dom regime and put nothing in its place, our view is that that is unlikely to happen. The Labour Party has explicitly said that it would have a regime for short stayers.

A number of countries have tax rules that distinguish between what are in effect permanent residents and people who have recently moved from another country, with the latter being treated more favourably. Doing this requires determining when (and how) preferential treatment is removed. The UK’s ‘deemed domicile’ rules provide a clear dividing line at 15 years; the remittance basis is no longer available after that point. Future reform could change when and how such a line is drawn for each of income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax. If significant reforms are being drawn up, it would be a good moment to consider which types of people we want to attract (or not deter from coming) to the UK; should the regime continue to be attractive to those with large offshore wealth or, for example, shift towards giving preferential treatment linked to income earned in the UK? Whatever form future reform takes, it will require careful work on the precise details, including on the treatment of trusts and the transition to a new regime.

Revenue should not be the only consideration in designing the taxation of non-doms. Nevertheless, much focus will be on how much revenue can be raised from non-doms. Chancellor Hunt is reportedly weighing up increasing taxes on non-doms because he faces tight public finances and wants to fund pre-election tax cuts – not a good reason for making such a change, whatever the pros and cons of any reform adopted. The Labour Party has said that it would use increased revenue from non-doms to fund increased public spending17 . It is impossible to say how much revenue could be raised without knowing exactly what the policy proposal is. Even once a policy is known, there will be substantial uncertainty. Policymakers should not shy away from sensible reforms just because the revenue consequences are uncertain, and the amounts at stake in this case are modest relative to the scale of the public finances. But reform does create a risk to the extent that a tax rise with a highly uncertain revenue stream (with potentially much larger downside risk) is relied upon to fund other tax cuts or spending increases that have much more certain public finance implications.

Author Acknowledgement: The authors thank Arun Advani, Carl Emmerson, Mark Franks, Mubin Haq, Paul Johnson and Andy Summers for comments on an earlier draft.

References

Advani, A., Burgherr, D. and Summers, A., 2022a. Reforming the non-dom regime: revenue estimates. CAGE Policy Briefing 38, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/manage/publications/bn38.2022.pdf

Advani, A., Burgherr, D. and Summers, A., 2022b. Non-doms: basics and the case for reform. https://arunadvani.com/papers/AdvaniBurgherrSummers_NondomBasics.pdf

Advani, A., Burgherr, D. and Summers, A., 2023. Taxation and migration by the super-rich. IZA Discussion Paper 16432, https://docs.iza.org/dp16432.pdf