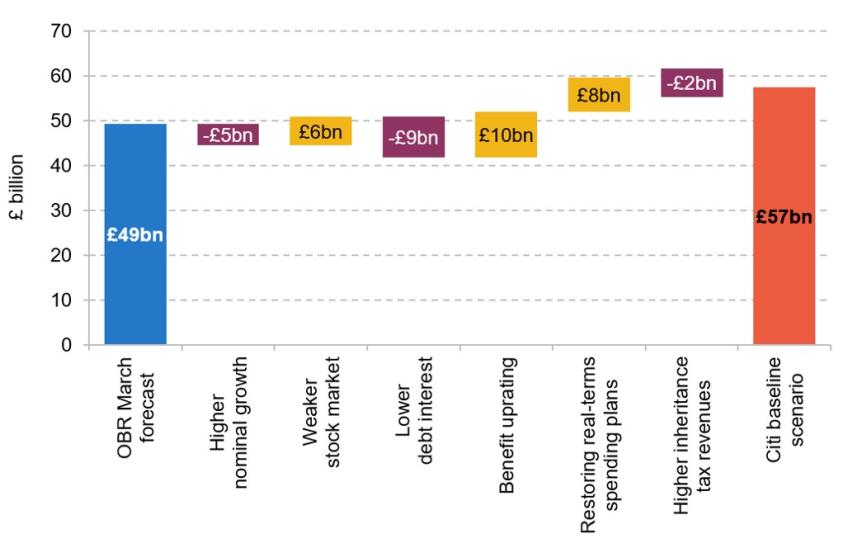

In the March 2023 Budget, the Chancellor presented an OBR forecast that had him meeting by a hair’s breadth his fiscal mandate for debt to be forecast to fall as a share of national income in 2027–28. Since March, the medium-term outlook for the public finances has, in many ways, changed quite substantially. We now expect (under Citi’s central scenario) slightly higher growth in the cash size of the economy, which will boost revenues. That is largely driven by higher inflation though, rather than higher real growth, which will also push up spending on social security benefits and public service spending (if the Chancellor wishes to maintain their real-terms generosity). These and other factors have offsetting effects on the public finances (as illustrated in the figure).

One key source of uncertainty is what will happen to interest rates: market expectations for future rates have been extremely volatile since Summer 2022. At the time of writing, these now imply £20 billion more spending on debt interest in 2026–27 than what the Office for Budget Responsibility forecast in March. However, Citi expect Bank Rate to fall more quickly, which would suggest debt interest spending could be £12 billion lower than the March 2023 Budget forecast.

All things considered, it is likely to be touch-and-go whether the Chancellor is on track to meet the letter of his fiscal rules. A lot will hinge on the precise assumptions made around the state of the economy five years hence, and what policies the Chancellor pencils in for the final year of the forecast (whether he actually plans to implement them or not).

In the current environment of high inflation and rising interest rates, tax cuts at the upcoming Budget would be extremely difficult to justify. The Chancellor should certainly avoid ‘paying for’ (certain) near-term tax cuts by pencilling in an (uncertain and difficult-to-implement) extension of the freeze to the personal tax allowance (in 2028–29) or by either tightening or extending the squeeze on public service spending beyond March 2025.

Changes to borrowing in 2027–28 between the OBR’s March forecast and Citi’s baseline scenario

Source: OBR’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook (March 2023) and authors’ calculations.

Key findings

1. The government’s fiscal mandate requires debt to fall as a share of national income between years 4 and 5 of the forecast period. While the idea of getting debt on a falling path over time has its merits, this specific target is much more poorly designed than most, such that focusing on ‘headroom’ against this target often gives a misleading impression of the health of the public finances.

2. No fiscal target is completely game-proof, or applicable to every single conceivable situation. But because it narrowly targets the change between year 4 and year 5 of the forecast, the fiscal mandate is overly sensitive to assumptions about growth, inflation and interest rates five years hence. It is also too easy to ‘game’ by pencilling in policy changes over a five-year period that the government has no intention of actually delivering. And we should remember that of the 14 Chancellors who have served over the 44 years since 1979, only three (Nigel Lawson, Gordon Brown and George Osborne) actually remained in post for more than five years.

3. The supplementary target, which requires borrowing to be forecast to be lower than 3% of national income, is very loose by UK historical standards. On virtually every occasion in the 43 years since 1980 (outside of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic), the Chancellor at the time could have increased planned borrowing without breaching this target.

4. The welfare cap, which currently places a limit on a measure of social security spending in 2024–25, is likely to remain on course to be missed – with a big factor being the increase in the number of individuals qualifying for incapacity and disability benefits. Rather than attempting to cut around £4 billion from spending in the coming financial year to bring it back to the limit specified by the welfare cap, this oddly designed fiscal target should join many other badly designed targets in the dustbin of history.

5. At more than 40% of national income, revenues are set to reach historically high levels. In part, these are financing higher spending on debt interest, which we forecast to remain above 4% of national income this year, a level which, before last year, had not been seen since the late 1940s. Overall public spending was forecast in the Budget to be 46% of national income this year, which would be only just below the pre-pandemic peak seen in 1975–76. Even by 2027–28, spending was forecast to be 43% of national income, which would be 3% of national income above what was spent in 2007–08, prior to the financial crisis and after a decade of New Labour governments. Of this increase, 1.2% of national income is explained by debt interest spending remaining elevated.

6. Under the March 2023 forecast, borrowing would be 1.7% of national income in 2027–28. If this materialised, it would be the lowest level since 2001–02. But despite this, debt was still only forecast to fall very slightly, highlighting the difficulty of preventing debt from rising as a share of national income when growth is weak and borrowing costs are high.

7. In the first five months of the financial year, tax revenues have run £13 billion, or 3%, ahead of the forecast, reflecting stronger nominal growth in the economy. As a result, borrowing is running £11 billion, or 14%, below forecast. Under Citi’s baseline scenario, some of this persists for the next seven months, leaving borrowing at £112 billion for the year, £20 billion below the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s March forecast for 2023–24 as a whole.

8. In March 2022, the OBR forecast that debt interest spending in 2026–27 would be £47 billion, but by March 2023 it had revised this up to £89 billion. Taking current market expectations for Bank Rate alone could push debt interest spending up by a further £20 billion to £108 billion. But market expectations are volatile. And whereas markets (at the time of writing) expect Bank Rate to be around 4% in 2026–27, Citi’s forecast is for Bank Rate to fall to 2% by that year. In that case, debt interest spending would be £12 billion lower in 2026–27 than forecast in March. That is a more than £30 billion swing in forecast borrowing depending on a decision over how best to forecast interest rates.

9. The impacts of higher inflation on the public finances are nuanced and partially offsetting. If inflation proves more persistent, it will result in higher tax revenues as well as higher spending on debt interest and working-age benefits. Spending plans for public services would be less generous than intended and the Chancellor would either need to top them up, or accept a reduction in scope or quality of services. Under a range of plausible inflation scenarios, we can confidently say that borrowing will be comfortably below the 3% cap imposed by the supplementary mandate, but will also be comfortably above what was forecast in Rishi Sunak’s final Budget as Chancellor in March 2022.

10. In a weak-growth environment, stabilising debt by 2028–29 is likely to rest on pencilling in another year of extremely tight spending plans, which will be very difficult to deliver when the time comes. Larger realised losses from the Bank of England’s quantitative tightening in a high-interest-rate environment could further add to debt (although not borrowing) and hence complicate meeting the letter of the fiscal mandate. Though, as outlined above, whether or not the government has debt falling in one particular year is not a good guide to the health of the public finances.

11. The case for tax cuts is weak. If anything, given the government’s appetite for public spending, there is actually a reasonable argument for a net tax rise to be set out for implementation over the medium term. In the current environment of high inflation and rising interest rates, a fiscal loosening would be extremely difficult to justify – especially given the high and volatile costs of servicing debt. The Chancellor should certainly avoid ‘paying for’ (certain) near-term tax cuts by pencilling in an (uncertain and difficult-to-implement) extension of the freeze to the personal tax allowance (in 2028–29) or by either tightening, or extending, the squeeze on public service spending beyond March 2025.