Fuelled by rising energy prices, CPI inflation in the year to July hit double-digits (10.1%), its highest level since 1982. In response to rising inflation, on 3 August the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee voted by 8-1 to increase Bank Rate from 1.25% to 1.75%. With the Bank forecasting CPI inflation to hit 13% later this year, further interest rate rises may be on the way. Indeed, the yield on government gilts implies that markets expect rates to reach almost 3% later this year and over 4% by spring next year.

Increases in interest rates are designed to rein in spending and tame inflation. One of the key ways that this happens is that a higher Bank Rate is passed through to mortgage interest rates, reducing households’ consumer spending power. Already, the effective interest rate for those households with variable rate mortgages (covering about 10% of the population, or 7 million people) has increased by about 1 percentage point (ppt) from 2.32% at the end of December 2021 to 3.27% in July 2022 – before the latest increase in Bank Rate. Because many people are on fixed mortgages, this has not yet passed through into a commensurate rise in interest rates measured across all mortgages.

Raising interest rates may be a necessary and advisable way for the Bank to meet its mandate to have inflation return to its 2% target over the medium term. But it is important to understand how rising rates will impact the financial pressures facing different households, especially alongside the huge rises in energy bills.

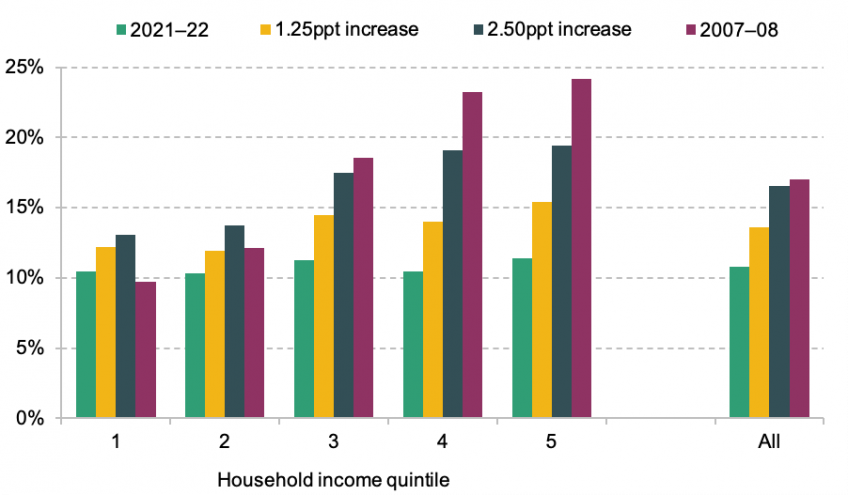

Figure 1 shows the estimated percentage of households spending more than 20% of their net monthly income on mortgage repayments in the last financial year (2021–22), and how that differs between high- and low-income households. Additionally, it shows the impact on this measure if all mortgage interest rates were to increase by 1.25ppts (the amount by which Bank Rate has risen so far since the end of the 2021–22 financial year) and by 2.50ppts (i.e. incorporating the same increase again as that which has happened since March, bringing Bank Rate to 3%). The figure also shows how these measures compare with 2007–08, the year before interest rates fell dramatically during and after the 2008 financial crisis.

Figure 1. Percentage of people living in households where mortgage repayments are more than 20% of income in 2007–08, 2021–22, and projected based on 1.25ppt and 2.50ppt increases relative to 2021–22

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey, various years.

Last year, the fraction of the population who lived in households with mortgage repayments worth more than 20% of disposable household income was 11%. Increases in mortgage interest rates push up the numbers paying over 20% of their income as a mortgage to 14% with a 1.25ppt rise and to 17% if there is a 2.50ppt rise. The latter would bring the share facing this repayment rate almost to the level reached in 2007–08, despite the fact that the share of mortgagors has fallen from 42% to 35% since then.

It looks as if there will be a bigger increase in the fraction of higher-income households spending more than 20% of their income on mortgage repayments. If mortgage rates rise by 2.50ppts, this share would rise from 11% to 19% for those in the top-income fifth of the population. (The top fifth of the income distribution is those with a disposable household income of at least around £44,000 per year for a childless couple.) This compares with an increase from 10% to 13% for those in the lowest-income fifth. (The lowest-income fifth have disposable household incomes less than around £18,000 for a childless couple.)

This pattern is mainly driven by the fact that high-income households are much more likely to have a mortgage than low-income households (54% of the top fifth versus only 19% of the bottom fifth). A group of concern may therefore be people who have a mortgage but have relatively low current income. For mortgage holders in the bottom fifth of the income distribution, a 2.50ppt rise in mortgage interest rates would mean a rise in the fraction paying more than 20% of their income from 54% in 2021–22 to 68%.

Of course, increases in interest rates do not feed through immediately to all mortgage holders. Those on fixed rate mortgages will be insulated from interest rate rises for a time. Over the period 2018–20, only 30% of mortgage holders had a variable rate mortgage. This figure may have fallen further over the two years since then. With around half of new fixed rate mortgages in 2019 being fixed for five years or more, there will be a substantial proportion of households insulated from mortgage rate increases for some time.

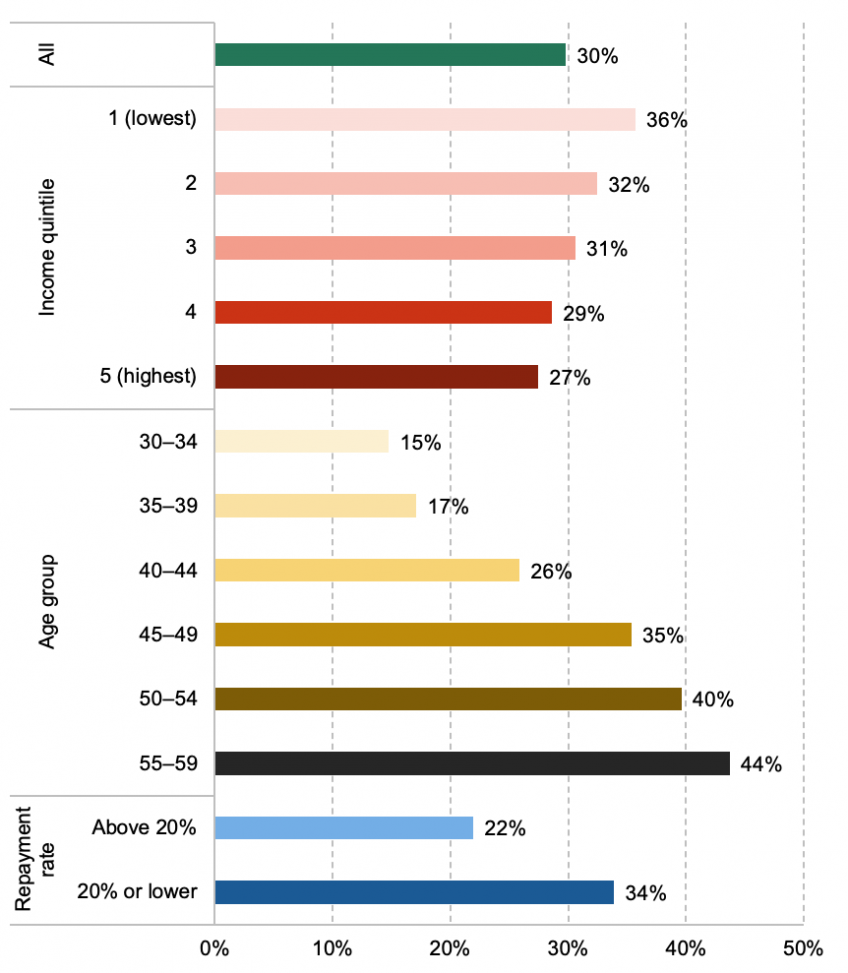

Which groups are likely to be more exposed to mortgage rate rises in the immediate term? Figure 2 shows the percentage of people who, among those in a household with a mortgage, are on a variable rate mortgage. We see that older people with mortgages and those with lower levels of household income are more likely to be exposed to interest rate rises in the short term. Among those in mortgage-holding households, 36% of those in the lowest-income fifth of the population have a variable rate mortgage, compared with 27% of those in the highest-income fifth. Looking at age differences, we see that 15% of mortgagors aged 30–34 have a variable rate mortgage compared with 44% of those aged 55–59.

Figure 2. Percentage of individuals in households with a variable rate mortgage, among those in households with a mortgage

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Wealth and Assets Survey, round 7.

Those whose mortgage payments were already relatively high, measured by repayments being more than a fifth of household net income, were somewhat less likely to have a variable rate mortgage than those whose repayments did not breach this threshold: 22% of individuals in households with high mortgage repayments were on a variable rate compared with 34% of those with lower repayments. This may be thought to be somewhat reassuring but these statistics also imply that there are over a million people in households already spending more than a fifth of their income on mortgage repayments who are immediately exposed to an interest rate rise.

Summary

As higher interest rates feed through to mortgage interest rates, the proportion spending more than a fifth of their after-tax income on mortgage repayments could get close to the levels last seen in 2007–08. A lot of the increase will come from those higher up in the income distribution, as they are more likely to have a mortgage in the first place. Although a smaller proportion of low-income people have a mortgage, the impact of rate rises on them might be of relatively greater concern. Not only will wider inflationary pressures be putting a greater pressure on their household budgets, but more than two-in-three low-income mortgagors could end up paying more than a fifth of their income on mortgage repayments, if mortgage interest rates rise by 2.50ppts. In addition, lower-income mortgagors, along with older people, are also more likely to be on a variable rate mortgage and so more likely to face such an increase coming sooner.