Safety concerns about school buildings have put capital spending on schools at the forefront of public debate. In this comment, we provide context by analysing trends in capital spending on schools in England, both in historical terms and compared with levels of need.

Historical decline in capital spending

Total capital spending on education in England is due to be about £7 billion in 2023–24. This reflects different types of capital spending. In 2023–24, about £1.8 billion is devoted to school maintenance and repair, with about £4 billion on new schools and other aspects of school capital spending. The remaining £1.2 billion is expected to be spent on further education colleges, as part of the government’s flagship further education (FE) capital transformation fund and in response to the reclassification of colleges into the public sector.

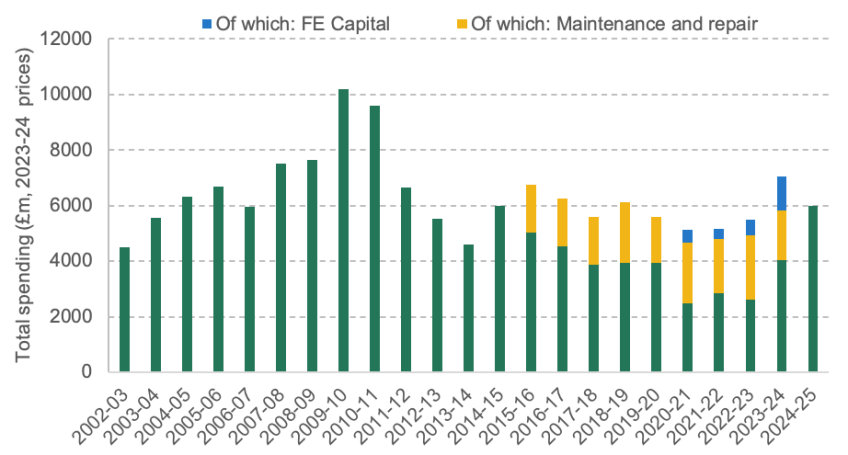

Figure 1 shows the historical trends in education capital spending in England back to 2002–03, including plans up to 2024–25. For recent years, we also illustrate the share taken up by school maintenance and repair, and spending on further education colleges. Before 2020, almost all of the spending will have been focused on schools.

As can be seen, capital spending tends to be lumpy over time. There was a large increase in spending in the late 2000s, with spending increasing from around £6 billion in the mid 2000s to about £10 billion in 2009–10 and 2010–11 (all in today’s prices). The large increase reflects the last Labour government’s Building Schools for the Future programme, with delays in this programme leading to the big upticks in spending in 2009–10 and 2010–11.

The Building Schools for the Future programme was largely cancelled and not replaced by the incoming government in 2010. This led to a large decline in capital spending down to about £4.6 billion in 2013–14, only just above 2002–03 levels. It then increased and averaged about £6 billion through to 2018–19. Capital spending has since declined to about £5.1 billion in 2020–21 and 2021–22, or about £4.7–4.8 billion if we exclude the new FE capital transformation fund. A further bounce-back to about £6 billion is expected for 2023–24 (excluding FE) and spending is expected to remain at this level in 2024–25.

Figure 1. Education capital spending in England over time, 2023–24 prices

Note: Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2023, 2020, 2019, 2014, 2013, 2010 (https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/public-expenditure-statistical-analyses-pesa) and 2008 (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/public-expenditure-statistical-analyses-2008). HM Treasury GDP deflators, June 2023 (https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp). Capital spending on further education (FE) capital taken from DfE supplementary and main estimates (Department for Education, various years). School maintenance and repair spending from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/school-capital-funding#eligibility-for-sca-for-the-2023-to-2024-financial-year.

The lumpiness and volatility of capital spending on education make it unwise to compare individual years. However, the three-year average up to 2023–24 (focusing on schools and excluding FE) was about £5.2 billion. This is about 26% lower in real terms than the three-year average of £7 billion up to 2008–09 and about 50% below the peak in 2010. Indeed, the three-year average of £4.8 billion up to 2022–23 was lower than any three-year period since at least 2004–05. Capital spending on schools is low in historical terms and lower in real terms than in the mid 2000s.

Focusing on school maintenance and repair spending, this rose from about £1.7 billion in 2015–16 up to £2.2 billion in 2020–21 and £2.3 billion in 2022–23 (all in today’s prices). This partly reflected one-off increases during the pandemic. Spending on school maintenance and repair is expected to decline back to about £1.8 billion for 2023–24, only about 3% higher in real terms than in 2015–16. Importantly, this is judged against overall inflation. It is highly likely that building and repair costs have gone up much faster than overall inflation, which will have further stretched spending.

Lower spending than needs

In June 2023, the National Audit Office (NAO) reported that the Department for Education (DfE) calculated it needed about £5.3 billion per year from 2021 to 2025 in order to maintain school buildings and mitigate the most serious risks. This was based on a survey of the condition of school buildings. It instead requested about £4 billion per year based on the rate at which it could increase spending. HM Treasury allocated about £3.1 billion per year. As a result, actual funding allocations from government have been more than 40% below government-assessed levels of need.

The current focus is on the risks posed by reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC), particularly that in ceilings, roofs and walls. However, it is important to state that this is not the only, nor the largest, area of need in terms of school repairs. As reported by the NAO, the DfE also recognises the safety risks posed by asbestos (contained within 80% of schools responding to a DfE survey) and system-built school buildings (particularly 3,600 school blocks with timber or concrete frames, which are more susceptible to deterioration and hidden structural defects).

Furthermore, ceilings, roofs and walls are not even the largest areas of need reported by the NAO. According to the NAO, the largest areas of need are electrical services (£2.5 billion to fix) and mechanical services, such as heating and ventilation (£2.1 billion to fix).

Spending on school buildings is low in historical terms and low compared with levels of need. This is the view of both the independent National Audit Office and the Department for Education itself. The current crisis illustrates just how costly failing to keep on top of necessary investment in buildings and infrastructure can be.