The Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat manifestos all commit to increase overall school spending in cash terms over the next parliament. Once expected inflation and student numbers growth are accounted for, Conservative plans would imply a real-terms fall in school spending per pupil of 2.8% between 2017–18 and 2021–22, which makes for a total cut of 7% between 2015–16 and 2021–22. Labour would increase school spending per pupil by 6% compared with present levels and leave spending per pupil in 2021–22 1.6% higher in real-terms than its historic high in 2015–16. Liberal Democrat plans would protect spending per pupil in real-terms at its 2017–18 level. All three major parties would continue the process of school funding reform, though with additional protections to ensure no school loses out in absolute terms. In this observation, we detail what these commitments would mean for the path of overall school spending in England and the prospects for continued reform of the school funding system.

Increases to the overall schools budget

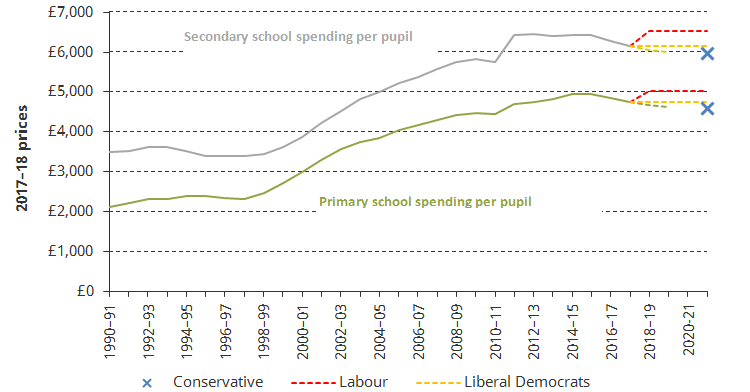

Under current plans for school spending in England, spending per pupil is set to fall by about 6.5% between 2015–16 and 2019–20. This fall increases to about 8% if we include some of the additional costs schools have faced in recent years such as higher pension contributions. Figure 1 shows that this would leave spending per pupil in 2019–20 at about the same real-terms level as it was a decade earlier, though still substantially higher than before the rapid increases over the course of the 2000s. Figure 1 then also shows how spending per pupil would evolve under each of the main parties’ commitments on school spending.

The Conservatives have committed to “increase the overall schools budget by £4 billion by 2022”. Once you strip out inflation, this equates to a real-terms increase in the schools budget of around £1 billion compared with the level in 2017–18. Taking account of forecast growth in pupil numbers this equates to a real-terms cut in spending per pupil of 2.8% between 2017–18 and 2021–22. Adding this to past cuts makes for a total real-terms cut to per-pupil spending of around 7% over the six years between 2015–16 and 2021–22.

Labour would reverse real-terms cuts to spending per pupil since 2015 and then protect it in real-terms over the course of the next parliament. This would require an increase in school spending of around £4.8 billion in 2017–18 prices compared with its level in 2017–18. If delivered, this would increase spending per pupil by 6% over the course of the parliament, leaving it about 1.6% higher in real-terms compared with its historic high in 2015–16 (the small real-terms increase results from compensating schools for some of the additional costs they have faced in recent years).

Under the Liberal Democrats’ commitment, spending per pupil would be frozen in real-terms over the course of the parliament, which would require a total increase in the school budget of around £2.2 billion compared with today.

These different commitments imply quite different levels of spending per pupil by the end of the next parliament. For instance, under Labour plans, we project secondary school spending will be about £6,500 per pupil, which compares with about £6,000 under Conservative spending plans.

Spending per pupil in primary and secondary schools: actual and plans

Notes and Sources: See Belfield, Crawford and Sibieta (2017). https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/8937; Authors’ calculations based on Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat General Election Manifestos; GDP deflator and Department for Education Pupil Projections .

Uncapping public sector pay

The figures above exclude any additional money schools may receive from removing the 1% cap on public sector pay increases. Exactly how much schools might receive is, however, uncertain. Labour have committed to following the recommendations of Pay Review Bodies, whilst the Liberal Democrats have committed to increasing public sector pay in line with inflation. If Pay Review Bodies recommended increasing public sector pay in line with private sector earnings, IFS researchers have used current forecasts for average earnings growth to estimate that this would increase the cost faced by public sector employers by £9.2 billion in 2021–22, of which about 30%, or £2.8 billion, would be for schools. Increasing pay in line with inflation would increase costs faced by public sector employers, relative to the 1% cap, by £5.3 billion, or about £1.6 billion for schools.

In reality, fully compensating public sector employers would probably require less funding than these headline numbers as cash-terms growth in spending per pupil would already allow for some of the planned increases in public sector pay. Nevertheless, any compensation given to schools would probably equate to a significant further increase in the schools budget over and above what is planned. For instance, £2.8 billion equates to 7% of the current schools budget. Any additional funding could be seen as simply compensating schools for higher costs, but one could also view such increases as providing for a higher quality of schooling than would otherwise be possible. For instance, the School Teachers Review Body has warned about the implications of the 1% pay cap on teacher recruitment and retention. Providing funding for higher pay increases could be one way to avoid such problems, though comes with a price tag.

National Funding Formula – Everyone’s a winner?

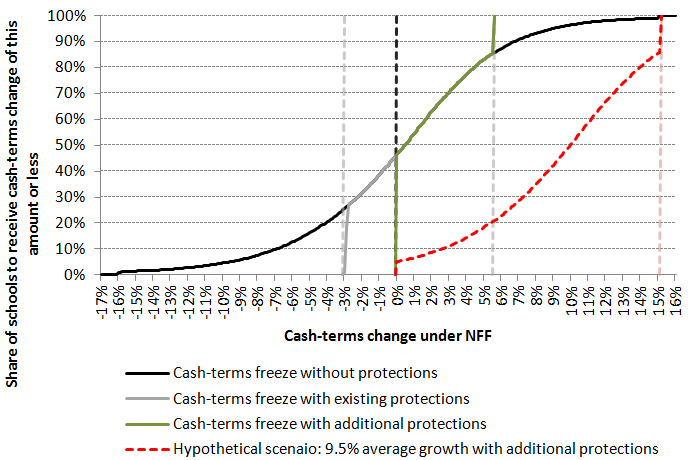

The outgoing government also proposed a national school funding formula in England to ensure similar schools receive similar levels of funding. Reforming the school funding system is long overdue, but doing so was always going to create winners and losers, at least in relative terms. Existing proposals came with transitional protections: no school would face cash-term cuts of more than 3% per pupil between 2017–18 and 2019–20 and no school would gain more than 5.6%. These protections cost £300 million and result in only 60% of schools receiving the funding level given by the formula in 2019–20.

All three major parties have decided to go further and have committed to ensuring that no school will face cash-terms cuts as a result of the national formula. This requires around an additional £350m of funding and leads to an asymmetric roll-out of the formula; the winners will still gain, but the losers will still not see their budget fall in cash terms. The above calculations ignore this as such funding is temporary and will gradually reduce as more schools move on to the formula. Though this might not happen that fast.

Starting with current policy, Figure 2 shows the proportion of schools due to receive gains and losses of given amounts as a result of the National Funding Formula between 2017–18 and 2019–20. The Figure shows three scenarios under the current policy of a cash-terms freeze in overall school spending per pupil: with no transitional protections; with the existing protections and with the additional protection that no school will face cash-terms losses. The striking result is that with a cash-terms freeze in overall spending and the additional protections that have been announced only 40% of schools are on formula in 2019–20.

As discussed above, each of the major parties has also committed to increase overall spending on schools. These increases in spending have the potential to ease the implementation by allowing some schools to move towards the formula level while their budgets remain protected in cash-terms or grow at a slower rate than the headline increase.

Conservative proposals imply a cash-terms increase in spending per pupil of around 4.5% between 2017–18 and 2021–22. This could allow them to get around 25% more schools on to the formula by 2019–20 if some see their funding frozen in cash-terms. However, this freeze would be on top of cash-terms freezes for some schools from 2015 onwards.

Figure 2. Cumulative distribution of changes between 2017–18 and 2019–20: primary and secondary schools

Notes and Sources: See Figures 10 and 11 in Belfield and Sibieta (2017). https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/9075

In principle, Labour and the Liberal Democrats have more headroom to get more schools on to the formula faster, as their plans imply larger increases in spending per pupil. However, they could only do so by delivering below inflation increases in funding per pupil to some schools. Labour’s proposals imply school funding per pupil increasing by 9.5% in cash-terms between 2017–18 and 2019–20. Under one hypothetical scenario set out in Figure 2 above, Labour could get most schools on to the formula by 2019–20 by simply imposing a cash-terms floor of 0% and a maximum real-terms increase of 5.6%. Only about 5% of schools would actually experience a cash-terms freeze and 80% would be on formula by 2019–20. However, this policy would still result in a significant number of schools facing real-terms cuts between 2017–18 and 2019–20. If instead Labour chose to protect all school per pupil budgets in real-terms this would preserve the current distribution of school spending and only about 40% of schools would be on formula by 2019–20, with further adjustment presumably required after 2019–20.

This highlights the difficulty of introducing the NFF at a time of constrained overall funding. Such a reform necessarily creates relative winners and losers, but with no overall growth in funding the reform must create absolute losers to transfer the additional funding to those that gain. Imposing additional protections does not solve this problem; it just delays schools’ transition to the true formula level.

Luke Sibieta, an Associate Director at IFS and an author of this piece, said:

“The commitments made by each of the main parties would imply quite different paths for school spending in the next parliament. Labour would increase spending per pupil by around 6% after inflation over the course of the parliament, taking it to just above its previous historic high in 2015. Proposals from the Conservatives would lead to a near 3% real terms fall in spending per pupil over the parliament, taking it back to its level in 2010.”