IFS Director Paul Johnson said:

“In broad brush strokes, that was the Budget we had been led to expect: big tax rises, more cash for public services, more borrowing and more investment. Look beyond the headline numbers, and there are two big judgements – one could say gambles – that the Chancellor seems to be making.

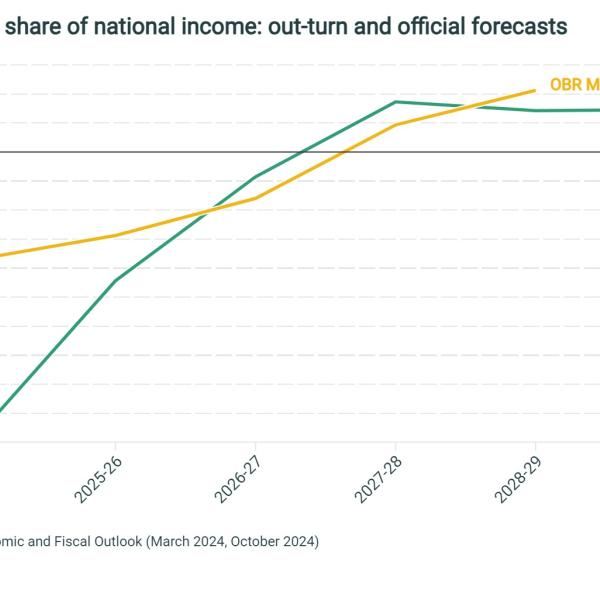

Let’s look at the headline numbers first. She’s taxing more. Tax is now on a path to 38.2% of GDP, its highest level ever in the UK, as the Chancellor seeks to shore up public services. But the Chancellor wanted to go further on spending, and so she’s also topping up public service budgets through borrowing in the next couple of years. We’re now set to borrow £28 billion more in 2025-26 than previously planned, and to spend £19 billion more on public investment: around a third of the extra borrowing is going towards higher day-to-day spending. By the end of the parliament, she’s promising to borrow only to invest. Meeting that ‘stability rule’ in 2029–30 relies on the assumption that day-to-day public service spending will grow much more slowly from 2026 onwards.

The first gamble is that a big cash injection for public services over the next two years will be enough to turn performance around, and that many of the temporary spending pressures won’t persist. If she’s wrong about that, and spending pressures don’t dissipate after two years, then to avoid cutting unprotected areas she may well need to come back with another round of tax rises in a couple of years’ time – unless she gets lucky on growth.

Which brings us to the second gamble: that this extra borrowing will be worthwhile. Under pre-election plans we were set to borrow an average of £59 billion per year over the next four years. We now expect to borrow an average of £85 billion. The hope is that the benefits – from more funding for public services in the next couple of years, and from more public investment throughout the parliament – will more than offset the costs. These costs include higher debt servicing costs but also, according to the OBR, higher inflation and higher interest rates than we’d otherwise have seen. A lot hinges on how well the government spends the money. The additional investment is extremely front-loaded, which doesn’t fill me with confidence on how efficiently it will be spent - if indeed it is spent in that timescale.

Was this a Budget for growth? The OBR pointed to a short-term sugar rush, as a result of the debt-financed spending splurge, but that turns into a modestly negative impact by the end of the parliament. In the longer term, extra investment, planning reform and greater stability should all help to boost growth, and the OBR said as much. They think the Budget will eventually boost output in a sustainable way, but only from 2032.

The biggest revenue-raiser was a very big increase in employer National Insurance contributions, both through an increase in the rate and a sharp reduction in the earnings threshold at which employers start paying. Given the need to increase taxes substantially it was always obvious that income tax, NICs or VAT would have to increase, and indeed that is what has happened. The OBR suggests that three quarters of the impact of employer NICs will be felt by employees, even if the changes don’t show up on payslips. Indeed, these tax rises partly explain why the OBR has downgraded its projections for real household income growth over the next few years. Somebody will pay for the higher taxes – largely working people. The employer NICs rise will further increase the incentive for employers to switch to contracting with the self-employed.

There were some welcome tax measures, including scaling back some inheritance tax reliefs. But there was little in the way of serious tax reform, and some deeply disappointing decisions. I have said again and again that stamp duty land tax is among the most economically damaging of all our taxes, and yet we have it increasing again. The increase may just be on second properties, but it is renters who will pay part of the cost as the supply of such properties falls. Almost unbelievably this government has followed the practice of its predecessor in freezing rates of fuel duties and not allowing the “temporary” 5p cut to expire, while raising other taxes dramatically and claiming to be focused on tackling climate change.

Taking a closer look at the government’s new spending plans, it’s remarkable the degree to which they’re front-loaded. Day-to-day public service funding is set to be 4.8% higher in 2024–25 than in 2023–24 (in part due to the large overspend identified in the summer) and is then set to grow by a further 3.1% in 2025–26. After that, spending is set to grow by just 1.3% per year – a rate of growth that would almost certainly involve uncomfortably tight settlements for many public services. Of the total real-terms increase planned over the next six years, around 60% is in place by the end of year two. Perhaps it will be possible to spend big now, address various backlogs and temporary pressures, and then slow the spending taps to a dribble later. But a government splashing the cash in the short term and promising to be more austere in future? Stop me if you think you’ve heard this one before.

It does bear repeating that the fiscal inheritance is truly dire. The spending plans inherited from the last government were never likely to survive contact with a Spending Review. Tax rises were always a near-inevitability. The new government’s embrace of fiscal reality is commendable – and would have been even more so had it occurred during the election campaign, and not only after the fact.

Finally, there were notable reforms to the fiscal framework. Day-to-day spending is to be met from within revenues, with the rule gradually moving from a five-year to a three-year rolling target. This is sensible – though the Chancellor hasn’t left herself much room for manoeuvre, with only £10 billion of so-called ‘headroom’. The £28 billion of extra government investment by 2028–29 will come from borrowing, within a new debt rule defined in terms of Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL). The Chancellor declined to take the opportunity to remedy the huge design flaws of the previous rule, choosing instead to just substitute in a different measure of debt. This switch hasn’t given her as much additional fiscal space as she might have expected, owing to volatility in the PSNFL forecast that might itself raise some questions about its suitability as a fiscal target. Minutiae of the rule aside, more borrowing means more debt, more spending on debt interest, and the OBR expecting interest rates to fall less quickly than they would otherwise have done. There’s no free lunch here. The challenge will be to make sure the money is spent well enough to make those costs worth bearing.”