Paul Johnson, Director of the IFS, said:

“That was not the quiet Autumn Statement we were promised. Before assessing the specifics, it’s worth getting a few things straight. The public finances haven’t meaningfully improved. The growth outlook has weakened. Inflation is expected to stay higher for longer. Higher inflation pushes up tax receipts by more than it pushes up spending on debt interest or social security benefits; but rather than use the proceeds to ease the ongoing ‘fiscal drag’ effects of threshold freezes, or to compensate public services for higher costs, the Chancellor opted to cut other taxes. His immediate cut to National Insurance will put more money into workers’ pockets when it comes in but won’t be enough to prevent this from being the biggest tax-raising parliament in modern times. These cuts will also not stop tax revenues rising to their highest ever levels. The “full expensing” cut to corporation tax is a welcome extension of the temporary cut announced in March and, alongside a slew of other reforms, does indicate that this was an event focused on medium term growth as well as a pre election giveaway.

Announcing immediate tax cuts in response to highly uncertain changes in assumptions about the UK’s medium-term economic prospects does not feel like a recipe for good management of the public finances, especially when some extra “space” is opened up by announcing another year of very low increases in public service spending, and cuts in investment spending, which may prove hard to deliver.

This may turn out to be risky even in the short run. His so called “headroom” against a rather loose fiscal target is minuscule and the OBR could easily take it away in the Spring Budget with some very small changes to forecasts. What will he do then? Certainly, whoever is Chancellor after the next general election is going to have very little room for manoeuvre.

All that being said, if the Chancellor was determined to cut taxes, he has picked a pretty sensible set of taxes to cut. Making full expensing permanent rather than temporary is welcome. Cutting rates of National Insurance is preferable to cutting rates of income tax and may help boost employment. But these tax cuts have been ‘paid for’, in effect, by letting fiscal drag become even more of a tax rise than previously expected and through a bigger squeeze on the real-terms value of public service budgets and an even bigger squeeze on public investment, which is frozen in cash terms. There’s a material risk that those plans prove undeliverable and today’s tax cuts will not prove to be sustainable.”

Economy, borrowing and debt - Isabel Stockton

Despite some near-term good news on growth this year, the OBR delivered a gloomier outlook for real growth going forward. Annual growth in the economy from 2024 to 2027 is now forecast to average 1.5% per year, compared with 2.1% per year in March.

Higher economy-wide inflation means that the economy is forecast to grow more quickly in cash terms. This boosts the outlook for revenues, and by more than the forecast increase in spending on debt interest, benefits and state pensions. In contrast, spending on public services does not automatically rise when inflation is higher.

This presented the Chancellor with a slightly improved outlook for borrowing. Rather than use this to compensate public services for higher inflation or to bank it in order to strengthen the public finances Mr Hunt chose to announce some sizeable permanent tax cuts: in particular to National Insurance contributions and corporation tax. While big, these are smaller than the tax rises announced since 2021 and therefore the tax burden is still forecast to continue rising to record UK levels.

The Chancellor also decided to extend the squeeze on public service spending to 2028-29. This is sufficient for debt to be forecast to fall in that year. But there are two key risks to this forecast. First, will the squeeze on public service spending, much of which is pencilled in for after the next general election, be delivered? Second, if the forecasts deteriorate between now and March, might Mr Hunt - as many of his predecessors have done - decide that he will accommodate higher borrowing and debt rather than announce new tax rises or spending cuts?

National Insurance Contributions - Robert Joyce

The headline measures in this Autumn Statement were cuts to the rates of National Insurance Contributions for employees and the self-employed. Taken in isolation, these put money back into the pockets of almost 30 million workers at a cost of around £10 billion per year, with anyone earning at least £12,570, or making profits of at least £6,725, per year benefitting.

The bigger picture is that these changes give back less than £1 of every £4 that is being taken away from households through changes to NICs and income tax announced since March 2021. Those takeaways are far less transparent than the smaller giveaway announced today - implemented as they are through multi-year freezes to income tax and NICs thresholds, which gradually bring more and more people into higher tax brackets, and especially so at a time of high inflation.

For an employee on average full-time earnings (£35,000 per year), the NICs cut announced today offsets the impact on their incomes in 2024-25 of the freezes in tax thresholds up to that point. But those freezes will continue to eat further into their incomes each year up to and including 2027-28, at which point they will be paying £249 a year more in direct tax overall as a result of all the changes since 2021.

For a given overall exchequer impact, those on lower incomes lose more from freezing tax thresholds than from raising tax rates, and hence they gain less from cutting rates than from increasing thresholds. Therefore the overall package that we now have – which reduces thresholds and partially offsets that effect by reducing rates – is a relatively regressive way of changing direct taxes.

When it comes to the overall structure of the tax system, the abolition of flat rate Class 2 NICs has the welcome feature of simplifying NICs for the self-employed. Cutting NICs for employees and the self-employed also slightly reduces the damaging incentive for people to work through their own companies instead to reduce their tax liabilities.

Full expensing for corporation tax - Isaac Delestre

Today, the Chancellor made ‘full expensing’ permanent. This allows companies to deduct 100% of qualifying plant and machinery investment immediately when calculating their taxable profits.

Isaac Delestre, a Research Economist at the IFS, said: “The Chancellor described the change as ‘the biggest business tax cut in modern British history’. It is not. The OBR estimates that the policy will cost almost £11 billion in 2028-29. But the ultimate cost of full expensing is much lower: around £1–3 billion a year (in today’s terms). This is because most of the up-front cost will be recouped in later years: under full expensing, firms deduct investment costs immediately which they would otherwise deduct gradually over time.

On balance, making full expensing permanent is preferable to allowing the policy to expire. However, there are serious trade-offs.The policy simplifies the tax system and removes the corporation tax penalty for equity-financed investment in qualifying assets. But it also creates a bias towards investing in qualifying plant and machinery rather than other assets, and increasing the large and problematic existing subsidy for debt-financed investment.

Ideally, the full-expensing policy would have been made permanent as part of a broader reform package that extended full expensing to all investment and changed the treatment of debt interest payments.”

Business rates - David Phillips

The Chancellor announced that business rates for properties with a rateable value of up to £51,000 would be frozen next April rather than increasing in line with inflation, which will cost £400 million a year. He also announced that a temporary reduction in bills for retail, hospitality and leisure businesses of up to 75% would be extended for one year, costing a one-off £2.7 billion.

David Phillips, an Associate Director at the IFS, said: “We’ve now seen four years of freezes to business rates for small businesses, and have a fifth year of temporary reliefs for the retail, hospitality and leisure sector.

While these will benefit businesses in the short-term, in the longer term, the biggest beneficiaries of cuts to business rates are likely to be landlords, as rents rise. And uncertainty about whether reliefs really are temporary or are likely to be permanent makes it difficult for both businesses and property owners and developers to plan. In particular, there is a risk some businesses in the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors may be made worse off in future: if the reliefs are believed to be permanent, rents are likely to bid up, leading to an increase in overall property costs if the reliefs are in fact allowed to expire as planned.

What we need is a long-term plan for business rates - including for the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors - rather than a series of repeated ‘temporary’ reliefs.”

Reforms to the Work Capability Assessment - Tom Waters

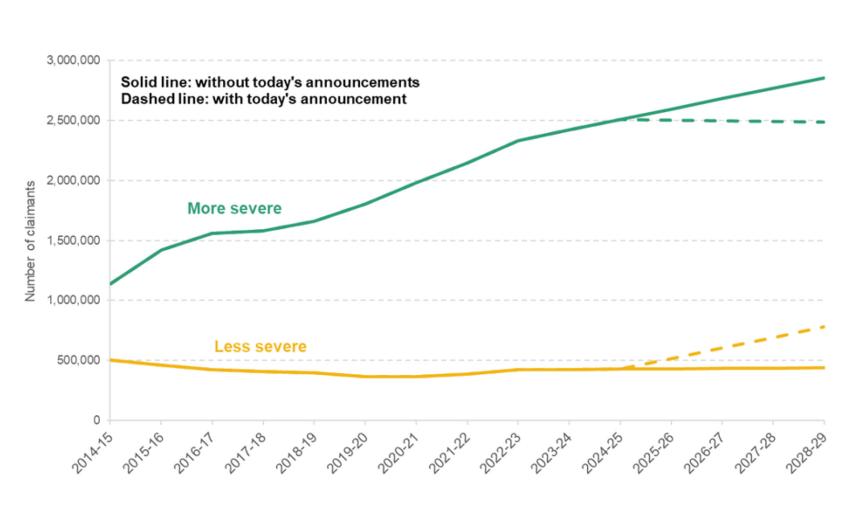

Benefits for those who are unable to work because of a health condition are assessed through a Work Capability Assessment (WCA). If the claimant is assessed as having a more severe incapacity, they get an extra payment - typically worth, for Universal Credit claimants, £4,690 per year. Those assessed as having a less severe incapacity, or being fit for work, get no extra money (though the former are not expected to look for a job). The Chancellor today announced a series of reforms that will raise the bar for being assessed as having a ‘more severe’ incapacity.

This is expected to save the government around £1 billion per year, with the OBR estimating that, by the end of the forecast period, 370,000 fewer people will be in the ‘more severe’ group. As is visible from the below chart, this reform only halts - and does not reverse - the steady increase in the number of people getting a more severe incapacity assessment over the past decade.

Number of claimants of incapacity benefits assessed as having a more or less severe condition

Notes: Years 2023-24 to 2027-28 are linearly interpolated.

Source: Authors’ calculations using OBR, “Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023” and OBR, “Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2023”

Tom Waters, an Associate Director at IFS, said: “Of the 370,000 people who will lose out from this reform, the overwhelming majority are expected to nonetheless remain on benefits, just with a lower level of income. Only 10,000 - 2.7% of those affected - are expected to move into work. Even with this reform, health-related benefit spending will continue to put more and more upwards pressure on the welfare bill.”

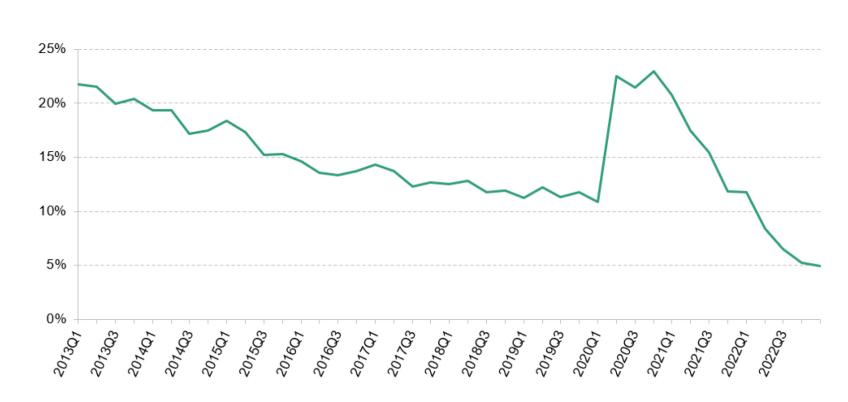

Local Housing Allowance Rates - Tom Wernham

Since April 2020, local housing allowance (LHA) rates, which cap housing benefits for private tenants, have been frozen. In that time, private rents for newly listed properties have skyrocketed, reducing the affordability of properties for benefit claimants. At the beginning of 2020, over a fifth of new properties available on Zoopla could be covered by housing benefit. But the huge growth in rents since then, while LHA rates have been frozen, means that fewer than 5% of newly listed properties can be covered by housing benefits under current policy, as shown in the figure below.

The Chancellor has announced that LHA rates will be increased next year back to the 30th percentile of local rent levels - before being frozen once again thereafter. The OBR suggests this measure will cost £1.3 billion next year. This will alleviate pressures on affordability for benefit claimants in the short term, before allowing them to build up again thereafter as long as rents grow in nominal terms.

This essentially repeats a manoeuvre from April 2020. Prior to the pandemic, LHA rates were also not indexed to local rents (but to CPI). When the pandemic hit, the government re-based the rates to the 30th percentile, but then immediately set a policy of freezing them going forward.

Share of private rental properties on Zoopla which can be covered by LHA

Source: Waters and Wernham (2023). “Housing quality and affordability for lower-income households”, Figure 4.11

Tom Wernham, a Research Economist at IFS, said: “The government’s decision to reset LHA rates to the 30th percentile of rents will alleviate the huge affordability pressures facing private renters on benefits. But the decision to then freeze rates once again rather than permanently linking rates to rents - at a time when rents on new listings are still growing by over 10% a year - means this is only a temporary solution. That the government is clearly unwilling to let LHA rates drift too far from rents obviously calls for an indexation policy that reflects that, rather than occasional and unpredictable ad hoc adjustments. The Chancellor will inevitably face further pressure to reset rates again in the not-too-distant future - but in the meantime, families on benefits face uncertainty on the affordability of their housing. This was a missed opportunity to return to a sensible uprating policy.”

Public service spending - Bee Boileau

Higher inflation has led to buoyant tax revenues, but does not automatically feed through into higher departmental budgets, which are fixed in cash terms. That means those budgets are worth less in real terms: they can purchase fewer goods and services. The upshot is that by 2027-28, the OBR estimates that the real value of departmental budgets will have been eroded by £19 billion. The government could have used the tax proceeds from higher inflation to compensate departments. Instead, they announced £20 billion of tax cuts.

Plans beyond 2025 imply making cuts to some ‘unprotected’ areas (like local government, or prisons) and imply big cuts to the level of public investment. Such are the scale of these planned cuts to investment that even Labour’s £20 billion-a-year boost to green investment might not be enough to offset them. The public finance forecasts are predicated on these tight spending plans being delivered.

A Spending Review due next year. Past experience strongly suggests that when Chancellors come to actually dividing the spending pot up between departments, they decide that the pot needs to be bigger after all, and announce a top-up. If history were to repeat itself, that would represent a threat to the public finance forecasts - and potentially mean that today’s tax cuts might not prove to be sustainable.