The proposed fiscal policies of Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak have been at the centre of the debates as to who should become Prime Minister next month. The backdrop to this has been a rapidly deteriorating outlook for the economy with rising prices leaving us poorer as an energy- and food-importing nation. The latest Bank of England forecasts, published two weeks ago, have inflation reaching a 40-year high of 13% in coming months and remaining elevated over the following year. This would lead to a considerable squeeze on household incomes, with the real economy being forecast to shrink continually from the third quarter of this year until the end of 2023. This report sets out an illustrative scenario for how this path of inflation and growth might affect government revenues and spending and discusses the resulting consequences for the scope for permanent tax cuts.

Key findings

- The latest Bank of England forecast is for inflation to climb to a higher peak, and to persist at an elevated level, for longer. As a result, its forecast implies that prices by 2024 will be 10% higher than forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in March. Higher prices will squeeze real wages, which are now forecast by the Bank to be 6% lower in 2024 than forecast by the OBR in March, and consumer spending, which is now forecast to be 3% lower in 2024 than the OBR forecast.

- Higher inflation, and higher interest rates, will push up public spending. Social security benefits and state pensions will automatically be pushed up by higher inflation: we forecast that spending on these items in 2024–25 will reach £300 billion, £16 billion higher than forecast by the OBR in March. Debt interest spending will be pushed up by a higher RPI and higher interest rates. We forecast that debt interest spending in 2023–24 will be over £100 billion, some £50 billion higher than forecast by the OBR in March. But as long as inflation subsequently drops back, we would expect much of the increase in debt interest spending to then fade leaving it ‘only’ £21 billion above the March forecast in 2024–25.

- Revenues will also be pushed up by higher inflation, although this effect will be tempered by weaker growth in real-terms earnings and household spending. We forecast that revenues in 2024–25 could be £37 billion higher than forecast by the OBR in March.

- Under our scenario, borrowing would be about £16 billion higher than forecast this year, rising to £23 billion higher next year. But by 2024–25, the third year of the forecast horizon and the year relevant for the government’s fiscal rules, the boost to revenues from higher inflation could be roughly sufficient to offset both higher spending on social security benefits and debt interest and also the impact of weaker real growth on revenues. That would leave the current budget surplus at around £30 billion in 2024–25, similar to what had been forecast in March – albeit with substantially higher spending and revenues.

- There is considerable uncertainty around these numbers. We can be reasonably certain that inflation will remain elevated until (at least) September 2023 and that this will lead to higher spending on debt interest this year and next, and to higher cash rates of benefits and state pensions in 2023–24 and 2024–25. In contrast, the outlook for nominal earnings growth and nominal consumer spending, and therefore the impact on revenues, is less certain.

- The two candidates for Prime Minister need to recognise this even greater-than-usual uncertainty in the public finances. Additional borrowing in the short term is not necessarily problematic – and indeed may be appropriate to fund targeted support. But significant permanent tax cuts would, unless matching spending cuts can be delivered, certainly increase the chances that the government fails to meet its own manifesto commitments on borrowing. Only last month the OBR warned that the public finances are already on an unsustainable long-term path: large, unfunded, permanent tax cuts would only act to make this problem worse.

1. The outlook for the economy

Forecasts for the public finances are inherently uncertain, and currently more so than usual. Two weeks ago, the Bank of England published its latest Monetary Policy Report, containing its latest projections for the economy. Only five months after the then Chancellor Rishi Sunak presented the latest official forecasts at the Spring Statement in March, it presents a much-worsened picture. It forecasts a recession, with the real economy shrinking by more than 2% over the five quarters to the end of 2023. At the same time, inflation is expected to be very high, and remain above the 2% target well into 2024.

These developments will affect both public spending and revenues through the way our tax and benefit system is designed and our debt is structured. This is even before any of the choices that are currently being debated by the two candidates to be Prime Minister – to provide more temporary support to households with the cost of living, to implement permanent cuts to taxes, or to make changes to public service budgets – are decided upon. In this note, we set out some of the different channels through which this new economic outlook is likely to affect the public finances.

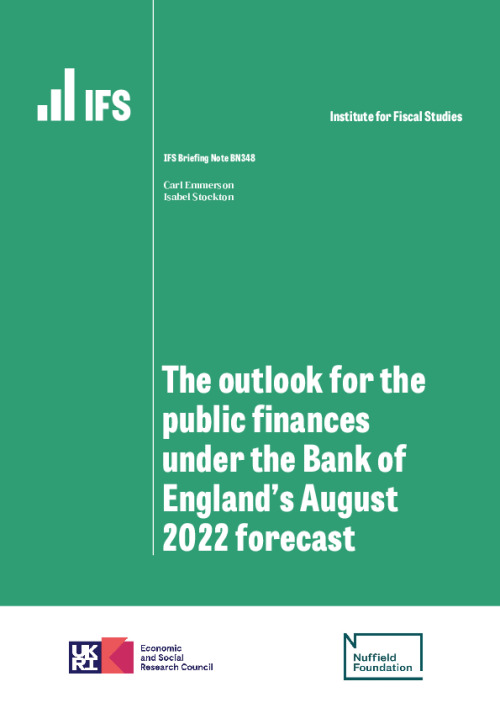

Figure 1.1 shows the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) – a measure of the level of prices that households face on average – as forecast in March of last year and of this year by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), and two weeks ago by the Bank of England. The outlook has worsened considerably. Inflation is now expected to not only be even higher next year than had been expected in March, it is also expected to remain at a high level for longer, with prices continuing to rise quickly in 2024. In that year, prices are now expected to be 10% higher than under the March 2022 forecast, an upward revision that is a third larger than between the March 2021 and 2022 forecasts.

Figure 1.1. Forecast price levels

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2021 and 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

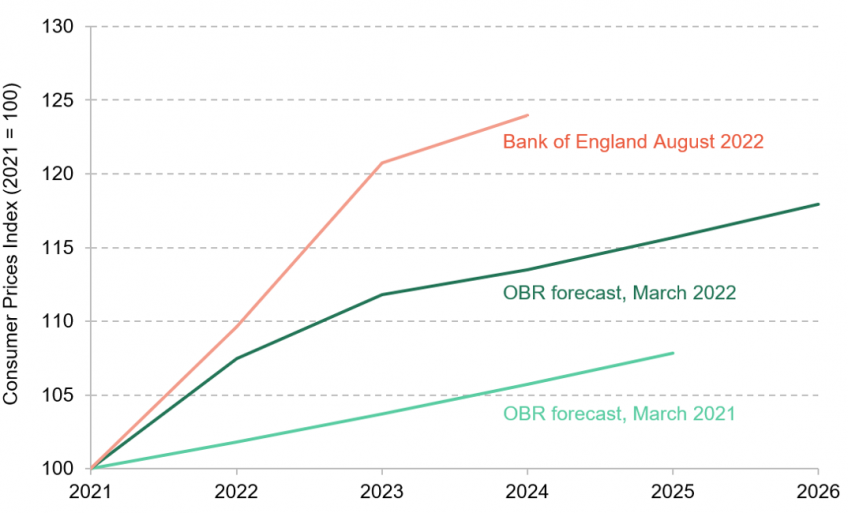

Figure 1.2 shows the paths of real earnings and consumer spending – in other words, consumer spending and earnings after taking account of (high and rising) inflation. Back in March, the OBR already expected earnings to fall in real terms, but the Bank now expects this fall to be sharper and to continue in 2024. As a result, by 2024 real earnings under the Bank of England’s latest forecast are 10% lower than in 2022, and 6% lower than forecast by the OBR in March.

Consumption is still expected not to fall in real terms, although to run at a lower level than forecast by the OBR in March. The Bank of England forecast has consumer spending in 2024 around the same level as currently, but 3% below what was forecast by the OBR in March. With falling real earnings, but household consumption just about holding up, the rate of consumer saving is expected by the Bank of England (and, albeit by a lesser extent, the OBR) to decline.

Figure 1.2. Forecast real earnings and consumption

Note: Earnings deflated by CPI. Bank of England series is growth in average weekly earnings; OBR series is growth in average annual earnings.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

2. Spending and revenues

Such high inflation puts huge pressure on both households and public services. But even without taking into account possible further packages of support to households, or top-ups to departmental spending plans that have become much less generous in real terms,there are a number of direct links between inflation and the public finances. On the spending side, higher inflation will push up spending on benefits, state pensions and public service pensions. In addition, higher inflation will push up spending on the index-linked part of government debt, while higher interest rates will also push up debt interest spending (with higher Bank Rate feeding directly, and immediately, into higher interest payments made on the reserves held at the Bank of England to finance its programme of quantitative easing). Inflation also has a positive effect on the public finances, via higher cash revenues. This is because taxes are levied on cash amounts, most importantly earnings and household spending. In contrast, departmental spending plans (which represent almost half of all government spending) are typically set in cash terms and do not automatically increase with inflation. By making these cash spending plans less generous, inflation implements ‘unintended austerity’.

2.1 Spending on benefits and debt interest

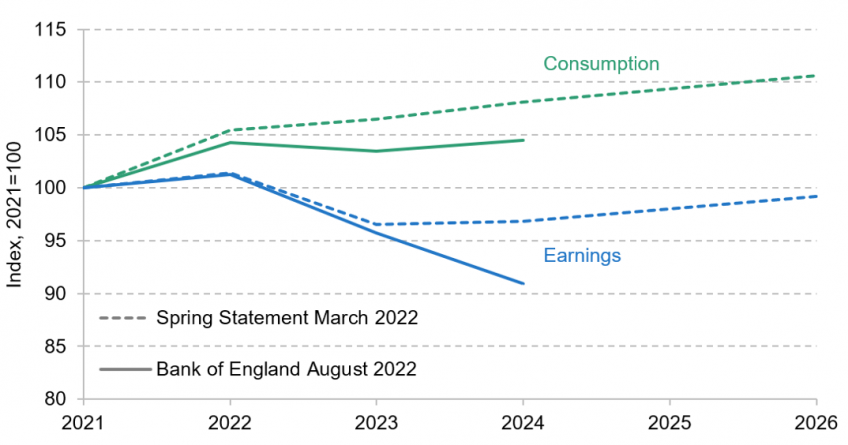

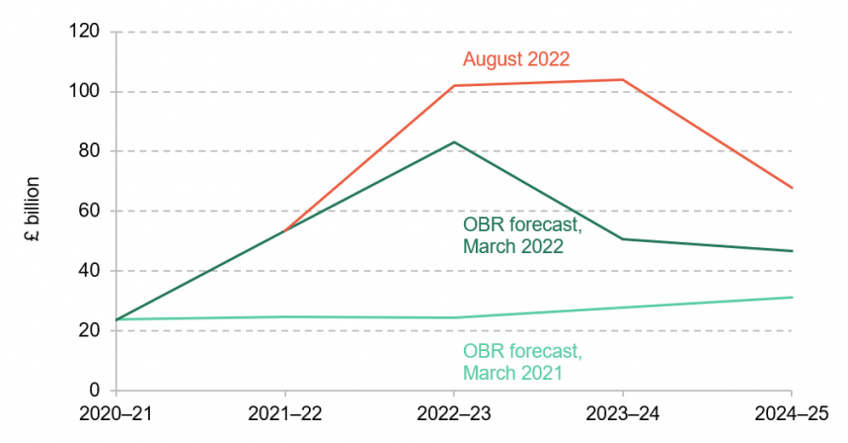

Figure 2.1. Forecast spending on social security and debt interest

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2021 and 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

Most working-age benefits are uprated each April in line with the previous September’s inflation. The state pension (both the basic state pension and the new state pension) increases by the greater of 2½%, inflation and the growth in average earnings which, at the present moment, will also mean uprating in line with inflation.

The fact that the rates of these payments increase with a lagged measure of inflation (the September 2022 rate of inflation determines the increase in April 2023) is problematic in periods when inflation rises as it is currently doing, as payments will temporarily fall behind the price level. Eventually, however, social security payments – and public spending on them – catch up with inflation. Of course, that can still cause problems for cash-strapped recipients of these payments, as it will not be until April 2024 that the rates of benefits would incorporate the October 2022 increase in household energy bills (since this increase comes after the date of the inflation rate used to set benefit rates for April 2023). And the fact that benefits for those out of work will eventually catch up with inflation will be of little comfort to someone who finds themselves unemployed in winter 2022 but who expects to move back into paid work before the April 2023 increase comes into effect.

In terms of the public finances, a permanently higher price level means that benefits and state pensions, too, will be much higher in cash terms in 2024–25. Using the OBR’s ready reckoners and the Bank’s new forecast for inflation, we would expect benefit spending to be £15–17 billion higher in cash terms from 2024–25 until the end of the forecast, to keep pace with the higher price levels.

Figure 2.2. Forecast debt interest spending

Note: Central government debt interest net of income from the Asset Purchase Facility shown.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2021 and 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

Another component of government spending that responds directly to higher inflation is spending on servicing government debt. About a quarter of government debt is index-linked, meaning that the cost of debt interest is directly linked to the Retail Prices Index (RPI). The Bank does not publish a forecast of this particular measure of inflation. As an illustrative scenario, we have calculated the likely impact on debt interest spending if the RPI moved one-for-one with the CPI. In the past, the ‘wedge’ between RPI and CPI has increased with large upward revisions, such as the one between October and March, because the RPI increases by more when inflation is more variable across goods – in other words, when some goods are increasing in price much faster than others, which is more likely to be the case when inflation is high overall.[1] Because of these patterns, our calculation more likely than not understates the eventual size and duration of the impact on debt interest spending, even taking the Bank’s CPI forecast as given. Because of these patterns, our calculation more likely than not understates the eventual size and duration of the impact on debt interest spending, even taking the Bank’s CPI forecast as given.

Under this assumption, debt interest spending would be above £100 billion in cash terms both this financial year and next, respectively £19 billion and £53 billion higher than under the March forecast. However, interest on index-linked debt depends on the rate of growth in the RPI, not on the price level. If inflation comes down, debt interest follows relatively quickly – unlike the impact on welfare spending, it would then be a temporary effect. In large part, what we would see is that the elevated level of debt interest forecast for the current financial year would continue for one more year. In 2024–25, when inflation is expected to be much lower under the Bank’s forecast, debt interest would therefore also fall sharply.

Nevertheless, it would still be elevated compared with the March forecast. This is not due, for the most part, to the direct impact of inflation but to the effect of higher interest rates. For this illustrative projection, we have taken current market expectations (averaging over the period from 1 August to 9 August) for Bank Rate – which anticipate that Bank Rate will be 0.8 percentage points higher in 2024–25 than forecast in March – and assumed they translate one-to-one into increases in interest rates on government bonds, or gilts.

[1] In addition, RPI includes mortgage interest payments, which are increasing due to rising Bank Rate and will continue to do so on average as more homeowners move off fixed rates and switch to a higher rate. CPI, in contrast, does not include owner-occupied housing costs.

2.2 Government revenues

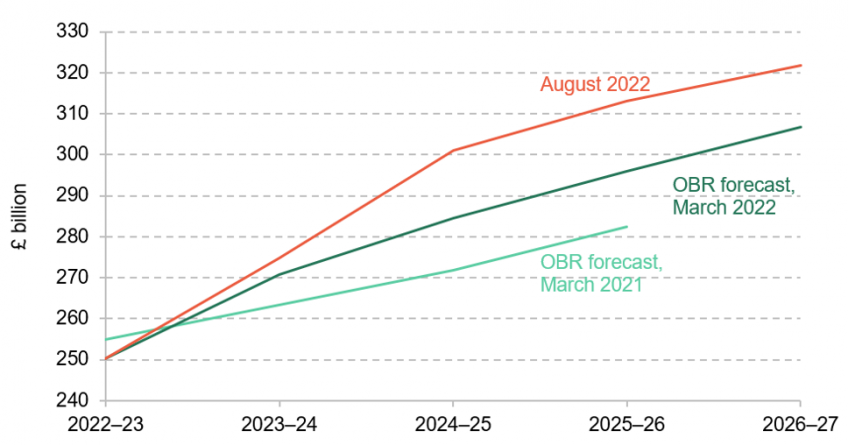

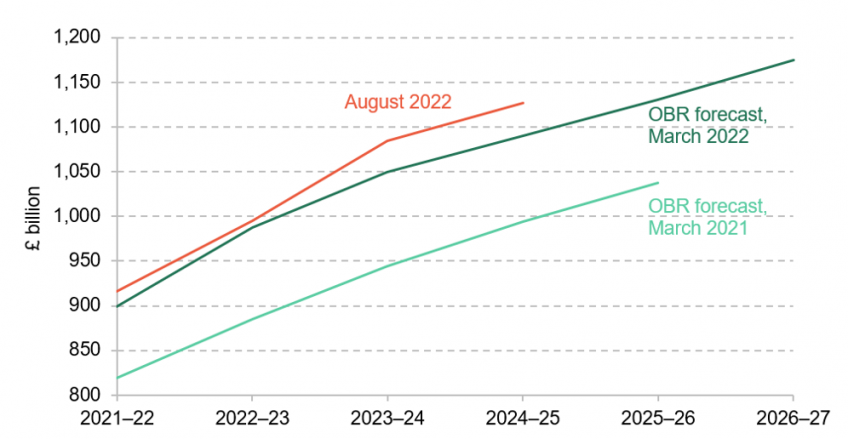

Figure 2.3. Forecast revenues

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2021 and 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

These effects on spending will be counterbalanced by higher cash revenues. The extent of this is very uncertain, even for a given level of consumer price inflation. It will depend on factors such as the composition of earnings growth, the evolution of (taxable) corporate profits, and the extent to which consumers are able and willing to spend some of their savings to compensate for lower real earnings.

To give a rough illustration of the potential size of this effect, we use the Bank’s forecasts for consumption and earnings in cash terms, combined with standard ready reckoners on the impact of growth in the cash size of the economy on revenues. This suggests that in 2024–25, the impact on revenues might cancel out higher spending on welfare and debt interest (the latter of which would have started to fall by then), leaving borrowing and the current budget in a similar position to where they were under the March forecast. In other words, the margin with which the government would be meeting its fiscal targets would be left more or less unchanged, unless and until it decided to implement additional tax or spending measures.

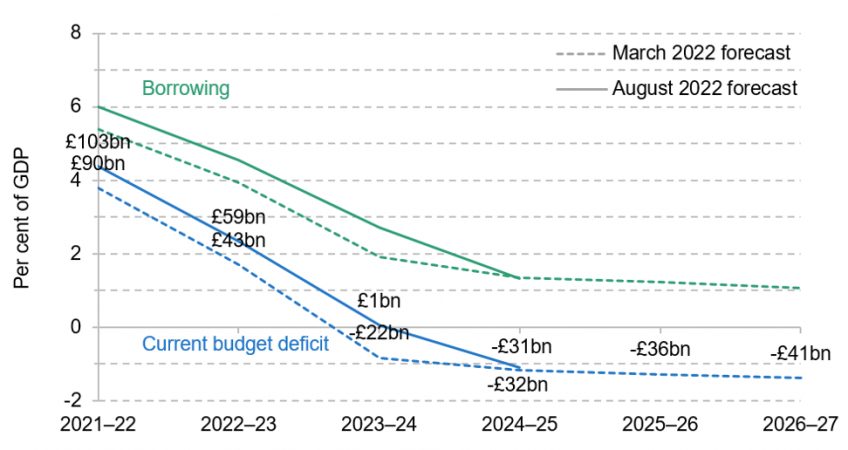

Figure 2.4. Forecast borrowing and current budget deficit

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2021 and 2022; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report August 2022.

So under this scenario – around which there is considerable uncertainty – borrowing would be about £16 billion higher this year than forecast in March, rising to £23 billion higher next year. But by 2024–25, the third year of the forecast horizon, higher inflation boosting revenues could be roughly sufficient to offset both higher spending on social security benefits and debt interest and also the impact of weaker real growth on revenues. It is, however, worth stressing that the increases in spending are more certain than how the outlook for revenues has changed. We can be reasonably certain that inflation will remain elevated until (at least) September 2023 and that that this will lead to higher spending on debt interest this year and next, and to higher cash rates of benefits and state pensions in 2023–24 and 2024–25. In contrast, the outlook for nominal earnings growth and nominal consumer spending, and therefore the impact on revenues, is less certain. A prudent prime minister and chancellor determined to deliver on the government’s existing fiscal targets and to manage the nation’s finances responsibly would be wise not to bank on higher revenues matching higher spending.