6.07 million people were on the waiting list for pre-planned NHS treatment in England in December 2021, more than one-tenth of the population. This figure has increased by around a third since the start of the pandemic due to the disruption that Covid-19 has wrought on the NHS.

The government has promised to tackle this backlog in “the biggest catch-up programme in the NHS’s history”, and last September announced £8 billion of dedicated funding over the next three years. On 8 February, NHS England published its plan for how it plans to tackle the backlog. The latest plan contains a number of ambitions and operational details on how the health service will increase capacity, but acknowledges that the overall waiting list may not be falling until early 2024. In this observation, we analyse the contents of the plan and how waiting lists are likely to evolve over the coming years under this recovery plan. We then present a number of scenarios to illustrate a range of possible outcomes, along with an interactive tool to allow readers to generate their own.

Use our interactive NHS waiting lists tool to explore how the waiting list might evolve in the next four years under various assumptions.

The contents of the plan

The headline ‘ambition’ (but importantly, not a formal target) is that by 2024−25 the NHS in England will be delivering 30% more elective activity than before the pandemic. This is the same ambition announced by the Prime Minister as part of the Build Back Better plan for health and social care in September last year, and is equivalent to a 10% increase in NHS volumes over-and-above what was already planned for in the NHS’ 2019 Long Term Plan.

This is certainly ambitious. To achieve it, the NHS will need to find a way to increase volumes of elective activity by around 30% in just three years. Though it isn’t clear exactly how ‘elective activity’ will be defined, placing this in some historic context lays bare the scale of the task ahead. Over the three years between 2016−17 and 2019−20, the number of people receiving treatment from the waiting list increased by just 4.3% (over the five years to 2019−20, the number grew by 14.8%). Even during the early 2000s, when real-terms NHS funding was increasing by more than 6% per year, NHS activity didn’t grow at the required rate: between 2002 and 2005, health service output (as measured by the ONS) grew by 22.5%.

The funding available for the NHS is unchanged from what was announced last year. Rather than announcing new money, this plan focuses on operational delivery and sets out a number of new waiting time ‘ambitions’ (again, not targets).

The plan focuses on four areas of operational delivery: increasing health service capacity; prioritising diagnosis and treatment; transforming the way elective care is provided; and providing better information and support to patients. The NHS plans (among other things) to offer more people the option of treatment in the private sector, to better target the patients who have been waiting longest, and to expand community diagnostic centres and surgical hubs.

There are four sets of new waiting time ambitions. The NHS aims to increase the speed of diagnostic tests; increase the speed of cancer diagnosis; reduce waiting times for outpatient care by ‘transforming the model of care’; and reduce the number of patients with long waiting times. For long-waiters, an area that has received particular media attention, significant progress has already been made. The number of people waiting more than a year fell substantially from its peak of 436,000 in March 2021 to 311,000 in December 2021, a reduction of 29%.

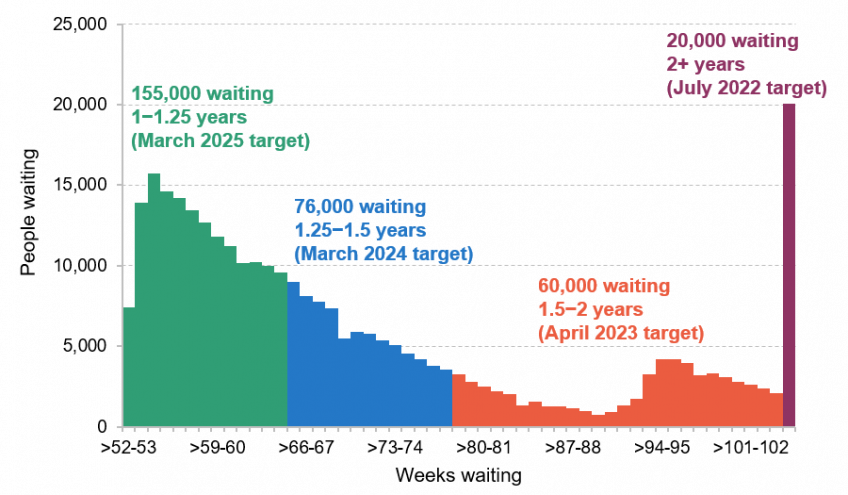

Building on that progress to date, the new ambitions for long-waiters are that in five months’ time nobody will be waiting more than two years, by April 2023 nobody will be waiting more than 18 months, by March 2024 nobody will be waiting more than 65 weeks (a year and a quarter), and that by March 2025 there will be nobody waiting more than a year. This final target has never been achieved by the NHS since comparable records began in 2007. It was closest to being achieved in 2013−14, when there were an average of just 370 patients each month who had been on the waiting list for more than a year. In February 2020, in the last month prior to the pandemic, this figure stood at 1,600.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of waiting times for those already waiting for more than a year in December 2021. Currently, there are 20,000 patients waiting more than 2 years, 60,000 patients waiting between 1.5 and 2 years, 76,000 patients waiting between 1.25 and 1.5 years and 155,000 waiting between 1 and 1.25 years. In the context of the overall waiting list (6.07 million) and the numbers treated each month (1.17 million in December), these numbers are relatively small. But treating them could still pose challenges if, for instance, they are concentrated in areas with hospitals that are particularly under pressure, or require specialist treatments with severe capacity constraints and longer waits.

Figure 1. The distribution of people waiting more than 52 weeks in December 2021

Source: NHS England’s RTT Waiting Times for December 2021. Note: this is the number of people waiting these times in December 2021, not a projection of how many will be waiting in the future. The target for each group refers to when the NHS aims to have nobody waiting for that length of time.

What might the plan mean for waiting lists?

It remains difficult to know what will happen to waiting lists in the coming years even if the NHS achieves its target of increasing capacity by 30% by 2024−25. Under the assumption that 50% of the patients who missed care during the pandemic eventually return, the NHS plan reports that waiting lists will likely only start falling in March 2024. But as we have previously argued, and as Sajid Javid rightly acknowledged when announcing the plan, the share of the 8 million or so ‘missing’ patients that will eventually come forward remains a huge known unknown. It is therefore sensible that the plan does not set targets for overall waiting list numbers, which are somewhat out of the NHS’s direct control, but instead focuses on treatment volumes, which the NHS can more readily control and plan to achieve.

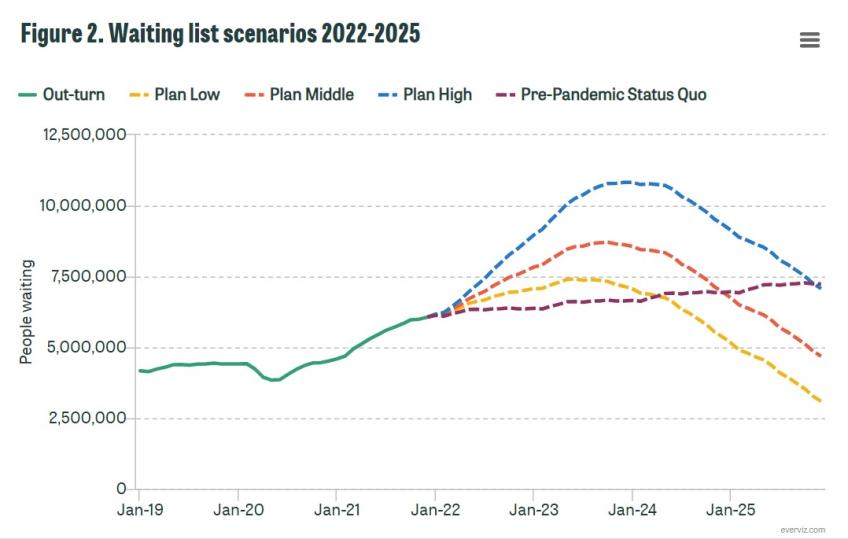

To demonstrate the uncertainty over the future path of waiting lists, Figure 2 shows four different scenarios for waiting lists over the next four years. The first three scenarios assume that the NHS successfully achieves its target of a 30% increase in capacity by 2024−25 but differ in how many of the patients who missed care return. The Plan Low scenario assumes that 30% return, the Plan Middle scenario assumes that 50% return (which the plan seemed to imply was the NHS’s baseline estimate) and the Plan High scenario assumes that 80% return. These three scenarios show that even with the NHS achieving its headline target for the level of elective activity, there remains huge uncertainty over when the waiting list will peak and how large the peak will be. In the Plan Low scenario, waiting lists peak at 7.4 million in June 2023 and then fall to below pre-pandemic levels by the summer of 2025. In the Plan Middle scenario, waiting lists peak at 8.7 million in October 2023[1], before almost reaching pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2025. In the most pessimistic scenario, Plan High, waiting lists peak in December 2023 at 10.8 million and remain several million above pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2025.

As we have previously argued, there is currently little evidence that those who missed care during the pandemic have started returning in large numbers to seek treatment. If this pattern continues, it is more likely that waiting lists will follow something like the Plan Low scenario, rather than the Plan Middle or Plan High scenarios. That would still see waiting lists continue to rise until mid-2023, but would result in a lower peak than previously feared. In other words, if predictions of large numbers of returning ‘missing’ or ‘hidden’ demand do not materialise, the backlog could start to be reduced well before March 2024. But while this may be ‘good news’ for waiting list figures, it would raise important questions about the wellbeing of the missing patients who never return for treatment. Some of those ‘missing’ people have died and others have chosen to go private, but many more have simply not sought treatment. At this stage we simply don’t know what this will mean for their welfare or health in future, nor what it implies about the necessity of the procedures that were missed.

In an extreme case, none of the ‘missing’ patients may return. But even then, if the NHS cannot find ways to effectively boost its capacity, waiting lists will continue to creep upwards, as they were doing prior to Covid-19. This is illustrated in the fourth scenario, Pre-PandemicStatus Quo, which assumes that none of the missing patients return, but that the NHS is unable to increase capacity above what was planned in the 2019 Long Term Plan (perhaps due to staffing or other constraints). In this case, waiting lists would not rise rapidly in the next year but would instead continue to rise steadily over the whole period as growth in capacity fails to fully keep pace with demand.

Figure 2 shows that in all of these illustrative scenarios, we can expect waiting lists to continue to climb before they fall. It seems virtually unavoidable that things will get worse before they get better. Treatment volumes will have been reduced over the winter due to the Omicron wave, and it will take time for the NHS to significantly ramp up capacity to above pre-pandemic levels. In the meantime, new patients will continue to join the waiting list – potentially at a rapid rate if a large chunk of the ‘missing’ demand returns over the months and years ahead. Both the funding and the plan for dealing with the NHS backlog are now in place, but the process of recovery from the shock of Covid-19 will take years.

Use our interactive NHS waiting lists tool to explore how the waiting list might evolve in the next four years under various assumptions.

[1] This is six months earlier than is implied in the NHS plan. This may be because the NHS assumes that increases in capacity will start later than we do, or that missing patients will return in higher numbers later than we do.