Increasing attention is being given to the ‘gender pension gap’ – the fact that on average women have lower private pension wealth and lower income in retirement than men.[i] But before rushing to conclusions about how to “fix” this, it is crucial to understand the drivers of any pension differences. This will determine what policy intervention – if indeed, any – may be desirable.

There are three main potential drivers of a difference in private pension wealth or income between men and women:

- Different labour market experiences: the ‘gender pay gap’, or differing lengths of working life among men and women;

- Different saving rates: men and women may differ in how likely they are to be offered a pension in their job, or tend to work for employers that contribute more or less to a pension, or tend to make different contributions themselves;

- Different investment strategies (in the case of defined contribution pensions): men or women may choose to invest in portfolios with a higher expected rate of return.

Importantly, the role of these potential drivers will have changed over time – for example, as the labour market attachment of mothers has changed, as final salary pensions have been reformed to career average schemes (which in particular reduced the generosity for long stayers and those with stronger pay growth – which affects men more than women), and as automatic enrolment has been introduced. This means that gaps in pension income today may reflect labour markets and pension arrangements from many years ago, and the gap in future pension income for current working age individuals may be quite different.

In an ongoing programme of work at IFS, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, we are examining in detail differences in pension saving rates between men and women that will contribute to a future ‘gender pension gap’ for today’s working age individuals.

In a first publication we have documented differences in average pension saving between male and female employees before the introduction of automatic enrolment. This shows that on average across all employees (whether saving in a pension or not) women of all ages actually contributed more as a proportion of their earnings each year than men. However, this was driven by the fact that women are more likely to work in the public sector, where contribution rates are typically higher. Examining average pension saving among men and women within each sector reveals a different pattern: the average saving rates of male and female employees were similar until around age 35 but then diverged – with average contributions continuing to increase with age for men but not changing for women.

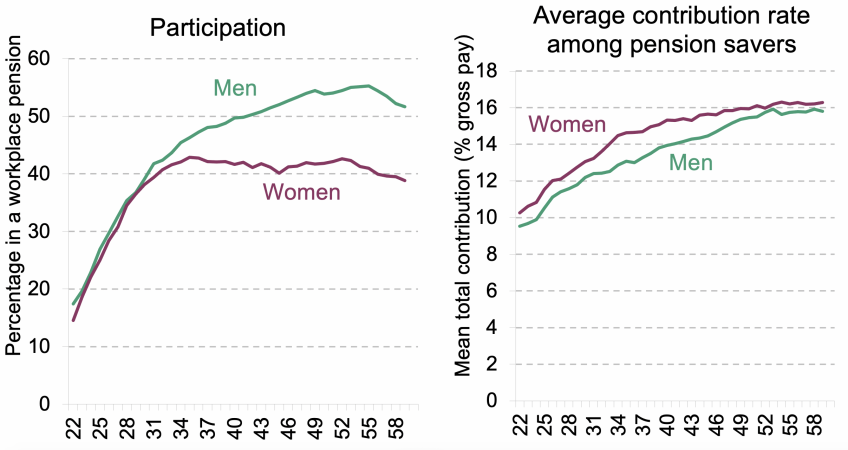

Figure 1 unpicks what is driving this pattern for private sector employees. It is caused by participation decisions (shown in the left hand panel). The proportion of men and women saving anything in a private pension is similar until around age 30, but then diverges with men increasingly likely to be saving in a pension with age, but women no more likely as coverage plateaus with age. Among those who are contributing to a pension, average contributions are actually slightly higher as a share of earnings among women than men (shown in the right hand panel).

Figure 1: Estimated age profiles of pension participation, and average contribution rates among contributors, for private sector employees

Notes: Estimated age profiles using data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, controlling for differences in saving by year and between generations. Source: Figures 1.10 and 1.11.

What might be driving differences in pension participation? The timing of the divergence mirrors the evolution of the gender gaps in pay, commuting and firm productivity, and suggests that the arrival of children and related employment decisions is an important factor. In our ongoing programme of research we are therefore examining whether the gap in pension participation is associated with the arrival of children, and the extent to which female employees received a different pension offer from their employer, or made different saving decisions when presented with a similar offer as male employees.

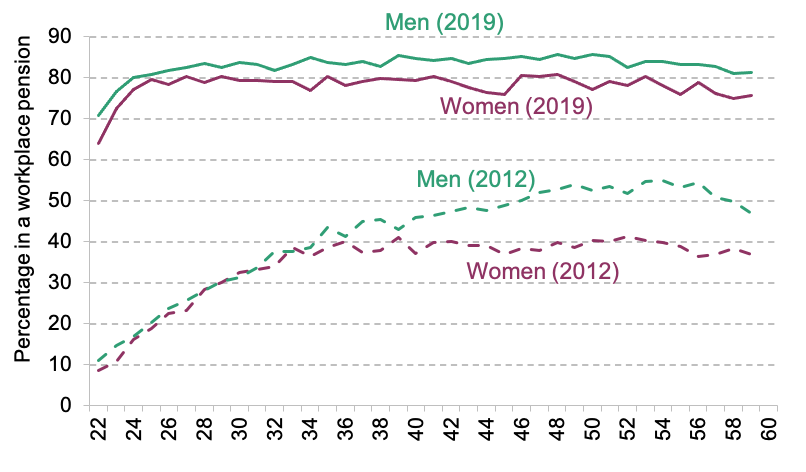

The introduction of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions has substantially changed pension saving behaviour – in particular, substantially increasing pension participation among employees targeted by the policy. Figure 2 shows how the proportion of male and female employees of different ages who were saving in a workplace pension in 2012 and 2019. The pattern in 2012 is similar to that estimated more formally in Figure 1. But the pattern in 2019 is now totally different: rather than participation diverging at a particular age, women are now slightly less likely to be in a pension at all ages than men (but the level of participation among both is considerably higher). Automatic enrolment will therefore have fundamentally changed the nature of the gender gap in pension saving rates going forwards.

This highlights the importance of examining gender differences in saving rates, rather than just accrued pension wealth or pension income. Focussing on the latter risks developing policies to fix a perceived problem that has already changed. It is important to understand more about the drivers of previous and current differences in pension saving rates between men and women, in order both to understand the wider consequences of automatic enrolment and to provide insight into what actions, if any, are warranted to address any continuing gender pension gap.

Figure 2: Proportion of male and female employees in a pension in 2012 and 2019

Notes: Authors calculations using Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2012 and 2019. Source: Figure 1.12.

This observation is part of an ongoing programme of research on ‘Pension Saving over the Lifecycle’ that is funded by the Nuffield Foundation. The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social well-being. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare, and Justice. It also funds student programmes that provide opportunities for young people to develop skills in quantitative and scientific methods. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and the Ada Lovelace Institute. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org

This work was produced using statistical data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, provided by ONS. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data.

[i] For example, an Early Day Motion on the issue was tabled in January 2021, and has so far been signed by 57 MPs. https://edm.parliament.uk/early-day-motion/58003/the-gender-pension-gap