Recent decades have seen rising wealth-to-income ratios. In England, increases in wealth have been concentrated among older generations. Those born in the 1980s have accumulated no more wealth than those born in the 1970s had done by the same age, but the parents of those born in the 1980s hold 40% more wealth than the parents of those born in the 1970s held at the same age. One consequence is that inherited wealth is on course to be a much more important determinant of lifetime resources for today’s young than it was for previous generations. New work by IFS researchers, funded by the Nuffield Foundation and released today, estimates that the average (median) inheritance of the 1960s generation will be worth 8% of average lifetime earnings for that generation, rising to 14% of lifetime earnings for the 1980s-born generation.

The aim of this research was to shed light on the inheritances likely to be received by those living in England who were born in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. We examine the likely size of future inheritances as well as the age by which they will be received, focusing on inequalities in each. This was all based on data collected prior to the current economic and public health crisis. It remains to be seen how current events will, in the longer term, affect some of the key factors that will determine future inheritances, such as asset prices and earnings. And even in the absence of the COVID-19 crisis, there would inevitably be much uncertainty about the medium- or long-term future. Nevertheless, the key patterns that we document are stark and highly unlikely to be qualitatively sensitive to these uncertainties.

Wealth – outside of that held in pensions – tends to be spent down only very slowly at older ages. This means that simply looking at the wealth of the parents of today’s younger generations gives a good first approximation to the inheritances that will be received. Parental non-pension wealth is very unequally distributed. One-fifth of people born in the 1980s have parents with wealth ‘per heir’ (i.e. after dividing it equally between their children) of less than £10,000, but one-quarter have per-heir parental wealth of £300,000 or more, with one-in-ten having £530,000 or more. On average, graduates born in the 1980s have parents with about 70% more wealth than the parents of people born at the same time who hold no qualification higher than GCSEs.

Using estimates of how wealth tends to be drawn down at older ages (based on what previous generations did with their wealth as they aged), and the expected longevity of older cohorts, we project forward the distribution of parental wealth to obtain a distribution of future inheritances for younger generations. We combine this with estimated inheritances for the minority of these generations who have already received them to give the overall distribution of past and future inheritances. Projecting forward trends in the earnings of younger generations allows us to compare the inheritances that we expect them to receive with what we expect they will earn from work.

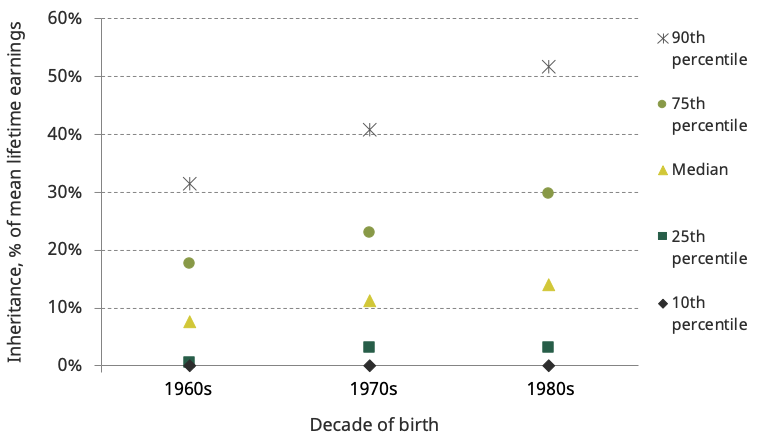

Inheritances are likely to become considerably larger, not just in absolute terms, but also relative to lifetime employment income. The chart shows our projection that the median inheritance of the 1960s generation will be worth 8% of average lifetime earnings for that generation, rising to 14% of lifetime earnings for the 1980s-born generation. While one-in-six of those born in the 1960s are projected to receive an inheritance worth more than 10 years of average annual earnings for that generation, this rises to one-in-three of those born in the 1980s. In fact, we find that more than one-in-ten of those born in the 1980s will receive inheritances worth in excess of half the amount of average lifetime earnings for their generation.

Distribution of expected inheritances received by decade of birth, as a percentage of mean lifetime earnings within the birth cohort

Source: Figure 5.4 of P. Bourquin, R. Joyce and D. Sturrock, Inheritances and Inequality within Generations, IFS Report 173, 2020, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/14949.

When will these inheritances be received? Rising longevity at older ages means the average age of people when their last-surviving parent dies is expected to rise from 58 for those born in the 1960s to 62 for those born in the 1970s and 64 for those born in the 1980s. For about a third of people born in the 1980s, this will not happen until they are in their 70s or older. These figures do not differ greatly between the high- and low-educated due to offsetting factors: the parents of the low-educated tend to die at a younger age but the parents of the high-educated tended to have their children when they were older. Of course, the point of death of the last-surviving parent is not necessarily the moment at which all wealth gets passed down, but it seems clear that the natural tendency will be for wealth transfers to occur later and later.

In summary, what looks first and foremost like an issue of increased wealth inequality between generations may also inhibit progress in addressing social (im)mobility, as the financial fortunes of younger generations become more tied to those of their parents.

The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org

A podcast featuring authors from this report is available here.