How much money are you going to have to live on in retirement? Perhaps, just like one in five Britons, you do not know.

This is not a surprise since there are so many shifting factors, or risks, to consider when thinking about retirement finances. You need to think about how much you’ll earn during your life, to what your employer will decide to contribute towards your a pension, and how much tax you will have to pay.

And then, even for the (fairly simple) state pension provided by the government, there is “policy risk” to think about. This refers to how big your pension pot will be by the time you retire, not to mention when you will able to claim it.

What this uncertainty means is that, almost irrespective of how much you earn, most of us face a lot of risks when it comes to our retirement finances. And unfortunately, you are likely facing more now than perhaps your parents did 25 years ago.

Back then, most of the uncertainty around pension pots came from not knowing how much you would earn over the course of your career. People typically had traditional occupational pensions, known as defined benefit or final salary pensions. These were basically a promise from an employer that they would invest enough money to ensure their employees were paid a particular amount from retirement at 65 until death. That amount would depend on a person’s earnings and length of service.

Some people did not have occupational pensions, but instead had state earnings-related pensions. With this type, higher earnings meant paying more in national insurance contributions, resulting in a higher state pension in retirement.

And so, 25 years ago it didn’t really matter how well the stock market did – if an employer’s investments did not cover their pension promise to employees, they had to top it up (and often did so, leading to companies having “pension deficits”). But for employees, it didn’t matter if they lived longer than expected, their company, or the government, would pay their pension for as long as they lived.

These risks – investment risk (how well the stock market and other assets do) and longevity risk (the risk of living much longer than expected and running out of money) – were not a big concern for people with pensions in the past. But the changing nature of UK pensions in recent years has caused these risks to be transferred from the government and companies to anyone saving into a future pension pot.

New retirement risks

For a variety of reasons (including the amount of risk employers had to bear in the past) barely any organisations outside the public sector offer traditional defined benefit pensions these days. Instead, on top of a state pension – which is now a flat-rate, no longer earnings-related – most people saving for retirement do so in a defined contribution pension.

At its core, a defined contribution pension is a tax-advantaged savings account that you and your employer contribute to, and which you can only access in your late 50s. When you do access it, you simply have a pot of money.

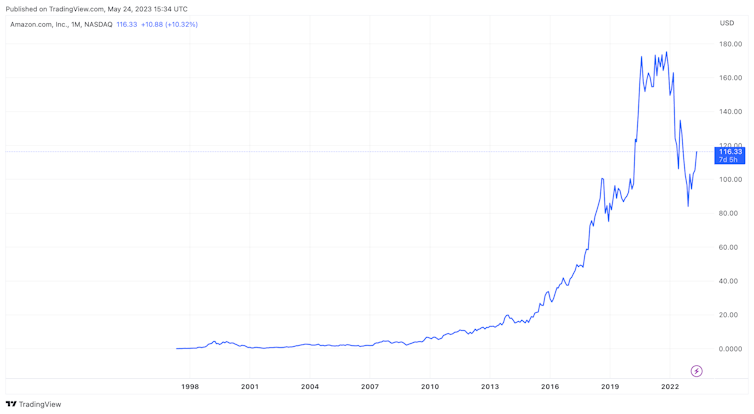

If you are very lucky in terms of what you have chosen to invest in (Amazon shares in the early 2000s maybe), your pot will have done very well. If you are unlucky (and you owned funds which were invested in companies that went bust, for example), you won’t have done as well as an Amazon-owning colleague – even if you contributed the same amount.

Amazon’s rising share price

Longevity risk is also now a factor to consider. This is the risk that you will live for a very long time and run out of money.

One reason for this is that, since 2015, retirees no longer have to turn their “pots” of defined contribution pension savings into an “annuity”. This is a stream of income that’s guaranteed until death.

Instead, most people simply spend their pensions pots any way they like now. But this means living much longer than expected increases the risk of completely depleting your private pension savings.

Pension risk transfer

One obvious question is: if pensions are now so risky, why don’t people pay to guarantee an income in retirement? That is, why doesn’t the government bring back annuities? When they were required, many people felt they weren’t getting a good deal out of these products – they were paying a lot upfront for only a small guaranteed annual income.

But while removing compulsory annuitisation is generally thought to be a popular policy – and it certainly gives people the freedom and opportunity to match their income with the way they want to spend in retirement – it also increases the risk of running out of private resources before you die.

In the past 25 years there has been a big transfer of investment and longevity risk from employers (who used to provide occupational pensions), from the state (who used to provide earnings-related state pensions) and from insurance companies (who typically used to sell annuities) on to people saving for retirement.

Managing these risks is now very important, especially as many working-age people may not realise just how much risk they are facing when it comes to ensuring financial security in retirement.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.