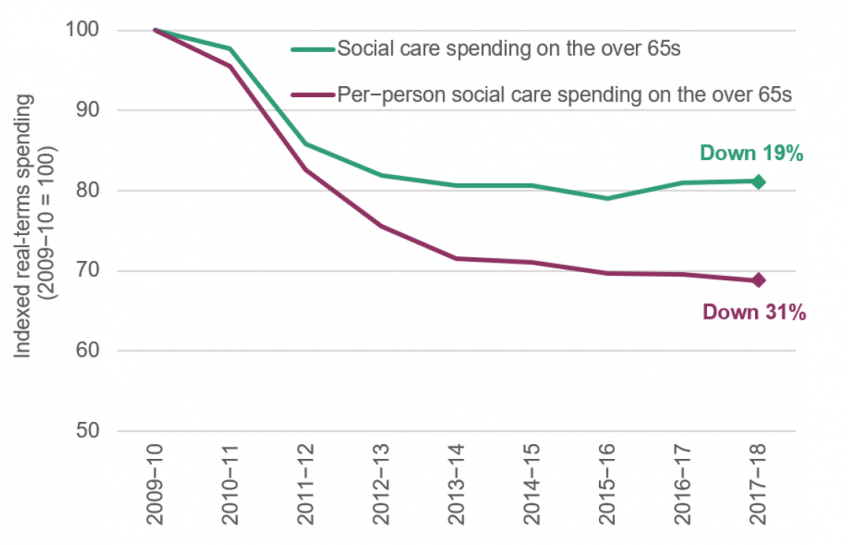

In England, councils are responsible for organising and funding the vast majority of social care services. Since 2010, these councils have experienced large cuts to their budgets, and have made substantial cuts to their spending on social care services in response. Between 2009−10 and 2017−18, mean per-person spending on social care for the over 65s fell by 31% (as shown by Figure 1). These cuts went hand-in-hand with a reduction in the number of people receiving government-funded social care. Meanwhile, NHS hospitals have been under considerable pressures in recent years. Accident & Emergency (A&E) departments, in particular, have had well-publicised problems with over-crowding and lengthening waiting times.

In a new IFS working paper, published today and funded by the Health Foundation, we examine what impact cuts to social care spending had on use of NHS hospitals. Exploiting the fact that the size of funding cuts varied considerably across areas, we examine the impact on the use and associated costs of three types of NHS hospital services: Accident & Emergency (A&E), inpatient care, and outpatient care.

Between 2009−10 and 2017−18, the average number of annual A&E visits for a person aged 65 and above increased by almost a third. We find that cuts to public spending on social care explain between a quarter and a half of this growth. On average, per-person spending on social care for the over 65s fell by £391 (31%) over the eight-year period. Our central estimate is that this directly led to an additional 0.07 annual A&E visits per resident aged 65 or over, or around one additional visit for every 15 residents in that age group. This was driven by both an increase in the proportion of over 65s attending an A&E department at least once, and by an increase in the average number of annual visits among those who attended.

The effects were most pronounced among older people and those living in poorer areas: the estimated increase in A&E attendance as a result of the cuts to spending among people aged 85 and above was twice as large as among those aged 65 to 74, and the increase was driven by people living in the most deprived (least affluent) neighbourhoods. This suggests that as well as having adverse health consequences for those affected, cuts to social care also had important distributional impacts. We also provide evidence that reductions in social care spending had adverse consequences for the performance of A&E departments, as measured by the share of patients who return within a week.

In contrast, we find no aggregate impact on the number of inpatient admissions or outpatient visits. This suggests that the additional visits to the A&E department rarely resulted in patients requiring extensive treatment. Consistent with this, we show that much of the increase in A&E visits is explained by patients presenting without a medical problem (with the diagnosis recorded by the doctor as ‘nothing abnormal detected’). This indicates that some older individuals, following a reduction in the quantity or quality of social care that they receive, ended up presenting in hospital with minor complaints that would likely have been better addressed in a non-hospital environment.

A&E departments account for only a small portion of overall hospital costs, because A&E care is relatively inexpensive to provide: if patients require more extensive and expensive treatment, they are typically admitted as an inpatient. The increase in hospital activity that we document was concentrated in A&E departments, and so the impact on overall hospital costs was very modest. We estimate that a £100 reduction in social care spending resulted in an increase in A&E costs of around £1.50, and found no statistically significant impact on inpatient or outpatient costs (when these are aggregated together, there is no statistically significant effect).

The increased costs imposed on hospitals were therefore nowhere near large enough to offset the initial public savings from reductions in spending on social care. However, this paper shows that these cuts did have both health and distributional consequences. Furthermore, increased use of A&E departments is likely distressing for the affected individuals, and we provide evidence that the performance of those departments suffered as a result of the influx of additional elderly patients.

The coronavirus pandemic has again brought to the fore the importance of coordination between hospitals and social care providers. As the government considers the future of social care funding post-pandemic, our work serves as another useful reminder that the NHS and social care should not be considered in isolation. There are many interactions between the two with important potential consequences for health, quality of life and the cost of service provision.

Figure 1. Real-terms local authority spending on social care for the elderly population in England, 2009−10 to 2017−18

Note: Figures shown are for our final sample of 140 local authorities in England. Per capita spending denotes spending per resident aged 65 and over. For full details of calculation, see Crawford, Stoye and Zaranko (2020).