In 2022, the UK government spent £12.8 billion on Official Development Assistance (ODA, or simply ‘aid’ in shorthand). That was equivalent to 0.51% of national income – a whisker above the current target level of 0.5%.

The target used to be 0.7% of national income. Following some big increases in ODA spending, that target was met in each year between 2013 and 2020. At the November 2020 Spending Review, the government announced that aid spending would be reduced to 0.5% of national income from 2021 onwards, judging that ‘at a time of emergency, sticking to 0.7 per cent is not an appropriate prioritisation of resources’. The government promised to return aid spending to 0.7% of national income ‘when the fiscal situation allows’.

The precise amount the government wishes to spend on aid is a political choice. But regardless of whether it is 0.5% of national income or 0.7% of national income, these are significant sums. It is important that this budget is managed and spent well – not least so that the UK gets the greatest bang for its buck when pursuing its developmental policy objectives. Yet the current state of affairs leaves a great deal to be desired. Here, we focus on three particular problems with the UK’s aid target and how it is put into practice.

The first of these relates to the fact that the government chooses to meet its target extremely precisely every single year (i.e. aims to spend 0.5% of national income and not a penny more – the slight additional spend in 2022 being a rare exception). This means that fluctuations in spending that can be counted as aid in one area or department can mean large in-year spending cuts or increases have to be made elsewhere.

The second problem relates to the challenge of trying to spend a particular fraction of national income without knowing what the level of national income will turn out to be. This introduces additional uncertainty into the process.

The third relates to the design of the rules set out by the government to assess ‘when the fiscal situation allows’ for aid spending to be increased back to 0.7% of national income. If the fiscal conditions are ever satisfied (and it is an if), the government’s policy seems to imply that aid spending would then need to be increased by 40% in a very short space of time: a recipe for potential inefficiency and waste. This would mirror the abrupt cuts that were made in 2021 – the pace of which increased the risk of getting poor value for money, according to the National Audit Office.

We conclude by setting out three ways to improve the design of the aid target, without advocating for any particular level of overall aid spending or for particular ‘types’ of aid spending.

Hard ceilings and perverse outcomes

Officially, and legally, the UK aid spending target is a floor: it requires the government to spend at least 0.5% (or 0.7%) of national income on aid. But, in practice, the government has also treated it as a ceiling. Despite the inherent uncertainties involved, the UK government has managed not to exceed its aid target by more than a tiny amount since 2013. It is reasonable to deduce that spending exactly the target amount has been official government policy. There are two challenges associated with this.

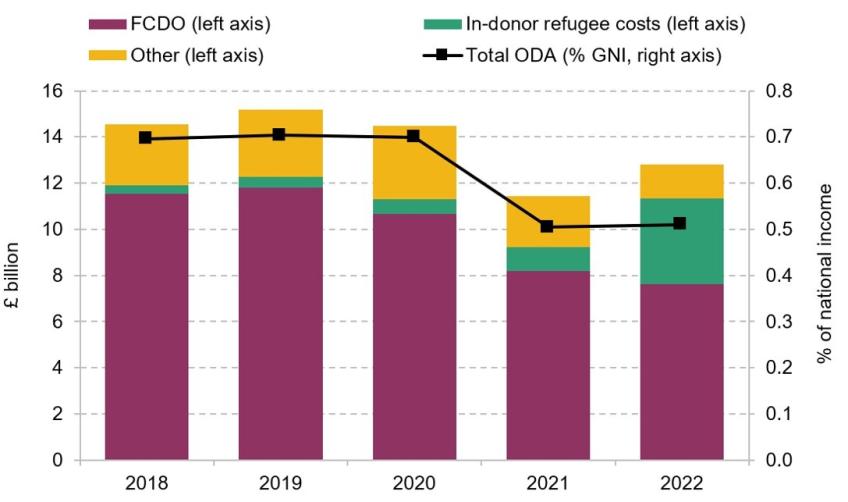

The first is the inherent unpredictability in aid spending, particularly when such a large portion of the budget goes towards ‘in-donor refugee costs’. These are the costs related to supporting asylum seekers and refugees during their first 12 months on UK soil (e.g. through the provision of accommodation and other subsistence support). These costs jumped by £2.6 billion – from £1.1 billion to £3.7 billion – between 2021 and 2022, and are now the largest single component of UK aid spending, making up nearly 30% of the total (Figure 1). This sharp increase partly reflects the costs associated with a number of special visa, humanitarian protection and resettlement schemes, most notably following the take-over of Afghanistan by the Taliban, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But it also reflects a broader increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving in the UK since 2021. None of this was predictable in advance. Other areas of the aid budget (e.g. humanitarian support following conflicts or natural disasters) can also be difficult to predict, but these account for a much smaller fraction of the budget and are more readily built in to Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) contingency planning.

Figure 1. Breakdown of UK ODA spending, 2018 to 2022

Source: Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, Statistics on International Development (various).

The second, and related, challenge is that there are multiple departments involved. The FCDO is the largest aid-spending department, responsible for 60% of total UK ODA in 2022. Yet the FCDO (and its predecessor departments) used to be responsible for a much bigger fraction of the total: 72% in 2021 and 79% in 2018 (as can be seen in Figure 1). Instead, the sharp increase in ‘in-donor refugee costs’ has largely been incurred by the Home Office, which was responsible for 19% of UK aid spending in 2022 (up from 2% in 2018). The sharp rise in ODA spending by other departments makes it more difficult for the FCDO to act as the ‘spender and saver of last resort’.

The government has gone some way to cushioning the impact of these shocks. At the Autumn Statement in November 2022, the Chancellor allocated an additional £2.5 billion over 2022–23 and 2023–24 ‘to help meet the significant and unanticipated costs’ of supporting those seeking refuge and noted that ODA would be ‘around’ (rather than exactly) 0.5% of national income going forward. Even so, this announcement came after in-year cuts had already been made in 2022 and did not prevent further cuts to other areas of aid spending in 2023 as the costs of refugees remained high.

We do not pass judgement here on what the aid budget should be spent on. The key point is that sharp (in-year) budget changes are not a recipe for efficient project management, maintaining effective partnerships or achieving good value for money. And with ‘in-donor refugee costs’ representing a much larger proportion of the budget, these in-year budget changes to other, less responsive – and in many cases more strategic – programmes are more likely. To offer an imperfect analogy, it is as though in order to meet the unexpected costs of the COVID-19 vaccine programme without breaching its predetermined NHS spending limits, the government had decided to abruptly cut its orders with other drug suppliers or to cancel all scheduled heart operations in NHS hospitals.

Nor is this just about the problems associated with in-year cuts to stay below a specified ceiling. The aid spending target also functions as a floor. Looking ahead, if the government’s Illegal Migration Act is implemented as drafted, it could mean that more than £2 billion of spending that currently counts towards the aid target would no longer do so (roughly speaking, because asylum seekers arriving irregularly would be barred from claiming and receiving asylum in the UK and would face detention and deportation, and so support for these individuals would no longer be ODA-eligible). This implies that the government could need to ramp up FCDO aid programmes by £2 billion in-year, to avoid missing its 0.5% target.

Additional uncertainty is created by the fact that each year, the government aims to spend a very particular fraction of contemporaneous gross national income (GNI), e.g. it aims for 2022 aid spending to be equivalent to 0.5% of 2022 GNI. There is inherent difficulty in accurately forecasting what the cash size of the economy will turn out to be, which means the government is always trying to hit a moving target. Particular challenges arise when there are large unanticipated economic fluctuations. Following the sharp economic downturn at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, large in-year adjustments to spending were made to maintain the ODA-to-GNI ratio.

In sum, the combination of an aid spending target that functions as a hard ceiling, the involvement of multiple departments, the difficulty of accurately forecasting the cash size of the economy, and – in particular – the unpredictable nature of spending on in-donor refugee costs has likely led to a raft of perverse and inefficient outcomes.

When will the fiscal situation allow?

The government has promised to return aid spending to 0.7% of national income ‘when the fiscal situation allows’. This has been defined as being when the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s fiscal forecast shows that the government is not borrowing for day-to-day spending (i.e. is running a current budget surplus) and that underlying debt (public sector net debt, excluding the Bank of England) is falling as a share of national income.

A further detail contained in the small print is important here. The government has confirmed that only ‘if it expects to meet the fiscal tests described above in the following financial year’ will aid spending be increased from 0.5% to 0.7% of national income. So only if the government expects to be running a current budget surplus and to have debt falling next year will its conditions be met.

There are two flaws with this set-up. First, these conditions are unlikely to be met in the current fiscal climate, and so this policy is effectively a permanent cut to aid spending dressed up as a temporary one. The government’s current set of fiscal targets require debt to be falling in five years’ time, and it is achieving that by the tiniest of margins – and even then only due to some fiscal sleight of hand. Given the state of the public finances and the growing demands on the state, the chances of the UK government being on track for falling debt and a current budget surplus in the first year of the post-policy-measures forecast are slim, for the foreseeable future at least. Even if the conditions were on target to be met, it would be perfectly possible for a Chancellor to increase spending, even as late as the autumn beforehand, to spend any surplus and avoid triggering a return to 0.7%. It would be more honest and transparent to say that UK policy is no longer to spend 0.7% of national income on aid.

Second, if by some economic or fiscal miracle the conditions were met, aid spending would – on the face of it – need to be increased by 40% (from 0.5% of national income to 0.7%) between one year and the next. It would be far more sensible to ramp up any additional spending gradually, rather than shovel it out of the door in a rush.

What might we do better?

However much the UK government wishes to spend on aid overall, the manner in which the aid budget is currently managed feels a long way from optimal. If the UK is to retain a target for aid spending, as both major political parties appear to be committed to, a few changes to the framework might improve things.

First, spending plans should better reflect the current uncertainties and fluctuations inherent in the aid budget – some of which the FCDO as the ‘spender or saver of last resort’ has no control over. Our preferred option would be to allocate some fraction of the overall level of desired aid spending to particular programmes and departments, and to retain an unallocated ‘ODA Reserve’ to meet unexpected demands and world events. The aim would be to provide certainty to pre-agreed programmes, while retaining the flexibility to meet (all but the very largest) unanticipated in-year demands (such as a spike in refugee numbers) out of the ODA Reserve. Importantly, holding the unallocated portion in an ODA Reserve would not require the government to know in advance which departments will need additional funding: in ‘normal’ years, the majority might go to the FCDO, but in 2022 the Home Office might have been the biggest beneficiary.

The precise level at which to set the allocated portion, relative to the headline aid spending target, would largely be a political choice. One option would be to allocate 90% of the overall level of desired aid spending (which would be 0.45% of national income per year with a 0.5% target) to particular departments and programmes. That could then be coupled with an ODA Reserve of 20% of desired spending (0.1% of national income with a 0.5% target), in anticipation that not all of it will be ultimately spent. If the ODA Reserve went entirely unspent, the government would spend 0.45% of national income. If the reserve was allocated and spent in full, it would spend 0.55% of national income. On average, we might expect the government to spend around 0.5% of national income. This might require the government to adopt some sort of rolling target, to allow for fluctuations in how much of the reserve is allocated.

Another option would be to allocate 100% of the government’s aid spending target (i.e. allocate 0.5% of national income with a 0.5% target), and treat this as the ‘floor’ on spending. The ODA Reserve would then be additional to that: with an ODA Reserve of 0.1% of national income, aid spending might fluctuate between 0.5% and 0.6% of national income. That would remove the risk of underspending the target in some years, but would mean spending more on average.

There is some precedent for the creation of an ODA Reserve: the 2021 Spending Review included a £5.2 billion ‘unallocated provision to take ODA to 0.7% of [national income]’ in 2024–25 as a separate budget line (a provision that was not, in the event, allocated). Our proposed change would simply make some sort of ODA Reserve a permanent feature of the framework, without any change to the overall level of aid spending.

Second, aid spending might usefully be allocated as a fraction of lagged national income – i.e. national income the previous year – plus an allowance for expected economic growth, rather than seeking to track in-year fluctuations in national income. That way, if the economy takes a sharp downturn, the government would not have to make immediate, in-year cuts to aid spending to hit the target. Instead, the FCDO (and other departments) would have a year in which to plan where the cuts might fall (because lower national income this year would feed through to a lower allocation for next year). With average nominal GDP growth of around 4%, allocating 0.52% of the previous year’s GNI would mean spending 0.5% of the current year’s GNI (i.e. hitting the target) on average. Such a change would not remove this element of uncertainty, but it would provide a greater degree of certainty over how much is available to be spent at the start of each calendar year.

Third, if the government retains its commitment to returning aid spending to 0.7% of national income when fiscal conditions allow, it should change how it assesses those conditions. It does not make sense to assess fiscal conditions only one year ahead and then plan for a rapid increase in spending if the tests are met. Given the nature of the government’s fiscal targets, and the fact that spending ought to be ramped up gradually, it would make more sense for the assessment to be more forward-looking. Our preferred option would be to assess whether the tests are being met in the third year of the forecast (by some pre-agreed margin) and if they are, to then treat the tests as having been satisfied, and plan for a gradual increase in aid spending over those three years. We note that under the OBR’s November 2023 forecast, the government’s conditions (for a current budget surplus and underlying debt falling as a share of national income) would be met in 2027–28, the fourth year of the forecast, and so this would not have triggered any increase in aid spending under our proposed framework. If the government is to stick to its current policy of assessing fiscal conditions one year ahead (to avoid having to change the legislation), it should plan to increase ODA spending back to 0.7% of national income gradually when its conditions are met, rather than all at once.

Conclusion

As in many other areas of spending, there are benefits to predictability and stability when it comes to aid. The current framework delivers neither. There is an important debate to be had about the appropriate level of UK aid spending, trading off fiscal considerations against the UK’s development policy objectives. But whatever level of spending is chosen, we ought to also debate how we might plan and spend the budget better.