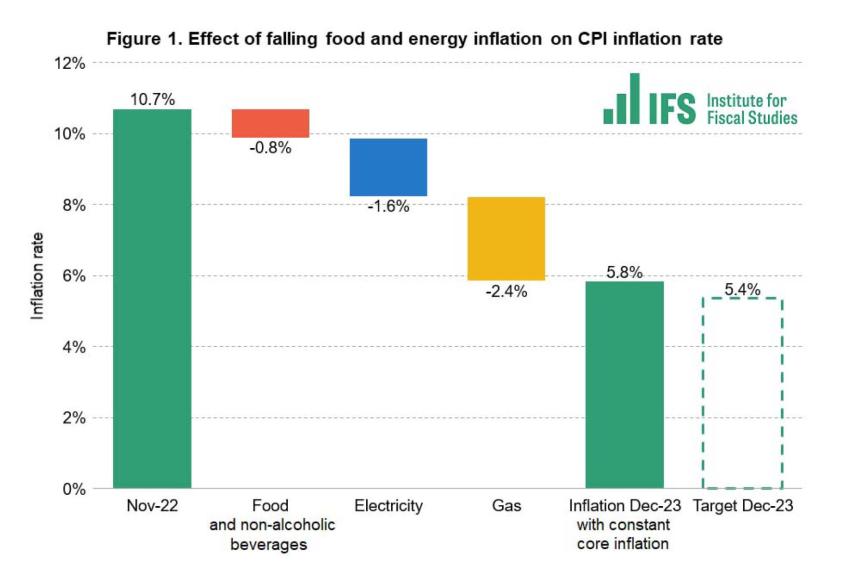

Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation in November 2022 (the latest data available to Mr Sunak in January) was 10.7%, implying a target rate of 5.4%. We assume that the aim is to reach this inflation rate in December 2023. In November 2022, the Bank of England had forecast CPI inflation in the last quarter of 2023 to be 5.2%, just below the target rate.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) announced today that the CPI inflation rate for July 2023 was 6.8%. This is the lowest rate since early 2022, which is of course good news for the Prime Minister – but it remains 1.4 percentage points above target. Will these trends continue and allow the Prime Minister to claim success?

While there is a great deal of uncertainty, some price changes in the coming months are more predictable than others. The biggest driver of the big swings in inflation has been the big changes in energy prices. The Ofgem tariff cap was set at £3,549 in October 2022, but the price consumers faced was the energy price guarantee of £2,500. Cornwall Insight has a good track record when it comes to predicting Ofgem’s energy price caps. Its latest predictions show the energy price cap returning to around £1,970 in October 2023, leading to significant negative energy inflation for the end of the year. These changes would knock 4 percentage points off the annual inflation rate in December 2023 relative to last November, getting the Prime Minister most of the way towards his objective.

There may also be welcome news from other categories of spending with volatile prices. Food prices have stabilised over the last couple of months – and stable prices mean that their contribution to the rate of inflation (the increase in prices) will fall. If these prices continue their recent trends, this will mean that inflation in December is a further 0.8 percentage points lower than it was last year.

Note: The bars indicate the negative contribution from food, electricity and gas inflation on the December 2023 inflation rate, compared with the November 2022 rate. Food inflation for December 2023 assumes month-on-month inflation rate for food and non-alcoholic beverages of 0.38% from July to December (in line with the rate of change from May to June).

Source: Authors’ calculations using CPI inflation data from the ONS and Cornwall Insight forecast of Q4 2023 Ofgem tariff caps from 27th July 2023.

If price rises for other goods and services also remain stable, this will be almost sufficient for the Prime Minister to meet his inflation target. Much therefore depends on what happens to goods and services excluding food and energy prices (so-called core inflation). Core inflation has remained stubbornly high since the end of last year, when it was 6.3%. The most recent figures for July show it is now 6.9%. The prognosis for core inflation looks mixed. On the one hand, producer prices for goods are now increasing much more slowly than consumer prices and we might expect this to start to feed through into lower consumer prices in the months ahead. On the other hand, rapid wage growth in the private sector could push core inflation rates upwards. After months of falling petrol prices, average fuel prices have also been increasing in recent weeks.

Thus, with only four months left to go, meeting the Prime Minister’s target looks far from the almost foregone conclusion that it looked like when it was set back in January. The progress that has been made is mainly due to the fact that commodity and energy prices are no longer increasing at the rates they were last year. The challenge is that core inflation remains stubbornly high, and considerably higher than was expected back at the start of the year.

The Prime Minister has never really had much in the way of levers to pull to bring inflation down. Interest rate setting is the preserve of the independent Bank of England, and rate changes famously only affect the economy with ‘long and variable lags’. Small changes in tax rates could help here and there. But they are unlikely to bring down inflation rates quickly and substantially enough to make much of a difference by December, and in any case tax rates should not be fiddled with simply to meet some arbitrary target.

Setting the target in the first place was always a bit of a gamble. With only limited time left, it looks like considerably more of a gamble than it first appeared.