David Phillips, an Associate Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said:

“In presenting its plans for next year, the Scottish Government likes to compare them with its original plans for 2023–24. Doing so suggests that planned day-to-day spending on public services is set to increase by 2.2% in real terms in the coming year.

“But funding for day-to-day spending this year was topped up by just over £300 million in the Autumn Budget Revision, and the Scottish Fiscal Commission estimates that the Scottish Government has a further £700 million available for in-year top-ups. Taking account of top-ups already made shrinks the increase next year to 1.4%, while taking account of all available resources this year would mean current plans for 2024–25 imply a real-terms cut of 0.4% to day-to-day public service spending.

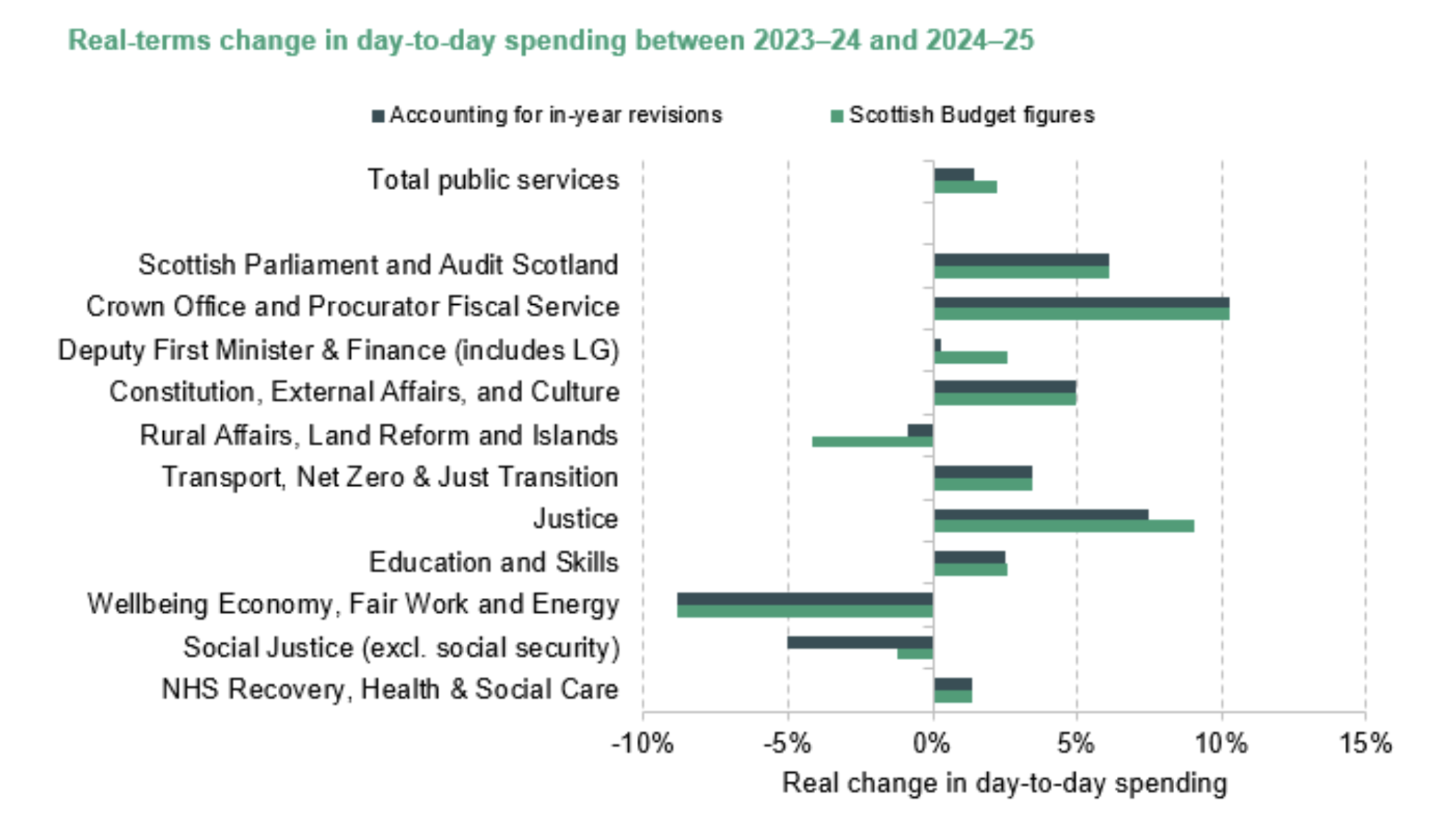

“Taking account of confirmed in-year top-ups to funding makes increases planned next year for Justice and Local Government look smaller than claimed by the Scottish Government, and cuts to the non-benefits parts of the Social Justice portfolio larger – although the cuts to the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio look smaller as funding for this year has already been cut back.

“No additional funding for day-to-day spending was provided to the NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care portfolio for the current year at the Autumn Budget Revision. But given bumper pay deals and the evident pressure on hospitals and GPs, it is almost certain that extra money will be needed before the end of the year. If it is, that could mean the Budget implies year-on-year real-terms cuts to this portfolio – although it is highly likely that additional funding would be found from somewhere (including cutting back spending on other portfolios) during the course of next year to support the NHS in such circumstances.

“As with this year, public sector pay deals are set to be a big financial challenge in 2024–25. In making its forecasts for tax revenues, the SFC assumes the average pay deal in the coming year will be 4.5%. This would be down from 6.5% this year, but would exceed the cash-terms increase in funding even on a Budget-to-Budget basis (around 4%), and is much larger than the increase compared with the latest position this year (around 1.3%). Pay deals at this level would therefore mean very difficult choices on staffing numbers and non-pay expenditure.”

Introduction

In our initial response to the Scottish Budget published on 19 December, we briefly discussed how planned spending on different service areas in 2024–25 compares with the initial budgets set for the current financial year, 2023–24 – the Scottish Government’s preferred approach. However, like the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC), our preferred approach is to compare plans for the coming year with the latest figures for the current year – which can reflect in-year additions or reductions to spending, and unplanned reallocations between services. Taking account of these can sometimes change the picture notably – as with when comparing funding last year and this for local government. So what do we find if we look more closely at the budget for 2024–25 and the latest spending and funding figures for the current financial year?

Comparing spending plans with the most recent figures for this year

This year, the most notable change to spending plans already confirmed in the Autumn Budget Revision was an increase of around £270 million on top of initial plans for what is termed the ‘Deputy First Minister and Finance’ portfolio, which now includes the majority of funding for Scottish local government. The vast majority of the top-up to this portfolio already confirmed is going to councils, largely to help fund pay deals for teachers and other council staff.

Taking this extra money into account, rather than increasing by 2.6% in real terms – as was suggested in the Scottish Budget documents – funding for the Deputy First Minister and Finance portfolio is set to grow only by around 0.3% in real terms between this year and next. We will come back to the implications of this for councils below.

The Autumn Budget Revision also saw a number of smaller changes to day-to-day spending for the Justice portfolio (which received £44 million to pay for the higher-than-previous expected cost of police pensions), the Social Justice portfolio (which received £30 million for Ukrainian refugee resettlement costs) and the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio (which saw its funding reduced by £30 million to free up resources for elsewhere). Overall, around £310 million of in-year top-ups to resource spending confirmed in the Autumn Budget Revision are excluded from the baseline figures for 2023–24 presented in the 2024–25 Budget document.

The figure below shows how the pattern of spending changes across portfolios differs from the figures presented in the Scottish Budget if we account for the in-year spending revisions in the Autumn Budget Revision. Alongside the Deputy First Minister and Finance portfolio, it shows that the biggest differences are for the Justice portfolio (which is set to increase by 7.5% rather than 9.1%), the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio (set to be cut by 0.9% rather than 4.2%) and the non-benefits element of the Social Justice portfolio (set to be cut by 5.0% rather than 1.2%).

Note: We subtract social security expenditure from the Social Justice portfolio here, and add non-domestic rates to the Deputy First Minister and Finance portfolio.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Scottish Budget 2024–25 and Autumn Budget Revision 2023–24.

It is important to note though that while the Autumn Budget Revision allocated £310 million to public services, the SFC estimates that over £1 billion of additional funding will ultimately be available in the current year compared with what was initially budgeted for. This is the result of additional UK government funding via the Barnett formula and the Migrant Health surcharge, additional planned drawdowns from reserves, and use of more of the receipts from offshore windfarm licences this year rather than next. The Scottish Government is also assuming there will be further funding forthcoming from the UK this year on top of the Barnett consequentials already announced in the Autumn Statement.

As we highlighted in our initial response to the Budget, taking into account all of the funding the SFC now expects to be available in the current year, funding for public services would be set to fall 0.4% in real terms next year (compared with increasing by 1.4% relative to revised autumn plans and 2.2% compared with the initial 2023–24 budget). Of course, it is possible that not all the funding available and that the Scottish Government says it will spend this year will in fact be spent – some could be carried over in reserves. If that is the case, we may see further funding announced for 2024–25 as the Budget bill proceeds through parliament in February.

Looking in more detail at health and social care funding

One area we may expect to get a top-up to funding for the current financial year is the NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care portfolio: it did not receive any top-up in the Autumn Budget Revision, despite higher-than-expected pay deals for NHS staff and the evident pressure on hospitals and doctors’ surgeries. The Welsh Government announced a £425 million top-up to health funding back in October, for example, and the UK government announced a top-up to English health spending of around £4 billion in the Autumn Statement.

If Scottish NHS funding is topped up this year, that will make the year-on-year change in funding for the NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care portfolio even less flattering than the 1.3% real-terms increase set out in the Budget documentation. It seems highly likely that funding will also have to be topped up next year too – which could mean reallocating spending from other portfolios unless sufficient additional funding becomes available.

Looking below the overall portfolio budget, it is worth noting that funding for what we might term front-line NHS services (the NHS boards, primary care, community health services, dentistry, eyecare, mental health, and payments to pharmacies) is reported to grow by 2.7% in real terms on a Budget-to-Budget basis: much higher than the 1.3% for the portfolio as a whole. Given that front-line NHS funding accounts for almost 90% of the overall portfolio budget, that is a big difference.

What explains this difference is a rather cryptic line in the Scottish Budget’s detailed appendices: ‘Other Board Services and Miscellaneous Income’. Whereas this was scored as a cost of £60 million in this year’s original budget, it is being scored as –£334 million next year. This swing from net-cost to net-income reduces the overall increase in the NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care portfolio. The accompanying notes are not that clear about what is driving this, or how these services and income relate to front-line NHS services. We will seek clarity on this in the New Year.

Looking in more detail at local government funding

With Scottish local government funding, it is always tricky to work out what is really going on given how funding comes from a range of portfolios. It has been made even trickier this year because of the way in which the Scottish Government has rolled a number of grants into its General Revenue Grant when restating the original budget for 2023–24, but included separate grants with the same or similar names (such as for the Living Wage) outside this core grant for the coming year, 2024–25. We will seek clarity on the relationship between these rolled-in and new grants, as well as any new responsibilities, before trying to give definitive figures for how overall funding for local government funding is changing next year on a like-for-like basis.

However, as already mentioned, the figures reported in the Budget will flatter the comparison as they exclude funding for pay deals found for the current financial year – but, in effect, include this funding in the figures for 2024–25. Moreover, the additional funding being provided to councils (£144 million) if they freeze council tax is not an addition to their overall funding – it simply replaces what they could raise from 5% council tax increases themselves. And, as the Fraser of Allander Institute has highlighted, some councils may have been planning on increases in council tax of more than 5%, and will face the difficult choice of whether to accept the equivalent of 5% from the Scottish Government or push ahead with plans for a bigger tax rise and forgo that grant funding.

Over the summer, the Scottish Government also consulted on increasing the relative tax rates applied to band E–H properties (approximately the quarter most valuable as of 1991 when properties were valued). These proposals ducked the biggest issue – revaluation – but were a small step in the right direction. And if councils had chosen to bank the resulting revenue rather than set lower band D tax rates than they otherwise would, the plans would have raised up to £180 million a year when fully rolled out, and perhaps £100 million in 2024–25 as they were phased in. Councils may have already been basing their early planning on the basis of this revenue boost, before instead a council tax freeze was announced at the SNP conference this autumn.

Public sector pay

Finally a word on public sector pay.

The Scottish Government has estimated that in 2023–24 pay accounted for over £25 billion of resource expenditure across the devolved public sector, including local government. That is well over half of day-to-day funding for public services.

Recent years have seen pay increase by more than initially planned – driven by high and persistent inflation, and the Scottish Government’s attempts to avoid industrial action. In May, the Scottish Government’s Medium-Term Financial Strategy was predicated on a central scenario of pay growing by 3.5% in 2023–24, on average, and 2% each year thereafter. Instead, the Scottish Government now estimates that the average public sector pay award in 2023–24 has been 6.5%, and the SFC is assuming increases averaging 4.5% next year as part of its income tax forecasts.

Increases in pay at that rate would slightly outpace the overall increase in spending next year even on a Budget-to-Budget basis (which is up around 4% on a cash-terms basis). Comparing the Budget with the latest position for this year (which is for funding for public services to increase by around 1.3% on a cash-terms basis) would suggest that paying for pay deals of this scale could involve some very tricky decisions on staff numbers and/or non-pay elements of budgets in the coming year.