Tomorrow will mark exactly ten years since the roll-out of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions began in the UK. From October 1st 2012, large employers were required to enrol their eligible employees – those aged 22 to 64 and earning more than £10,000 a year – into a workplace pension scheme. This was gradually extended to successively smaller employers, and since 2018 this requirement applies to all employers.

This policy has had a tremendously positive impact on private pension participation rates in the UK. However, the path ahead is less straightforward. This comment discusses recent IFS research on the effect of automatic enrolment, and some of the challenges that lie ahead.

Success story of increased participation – across all eligible workers.

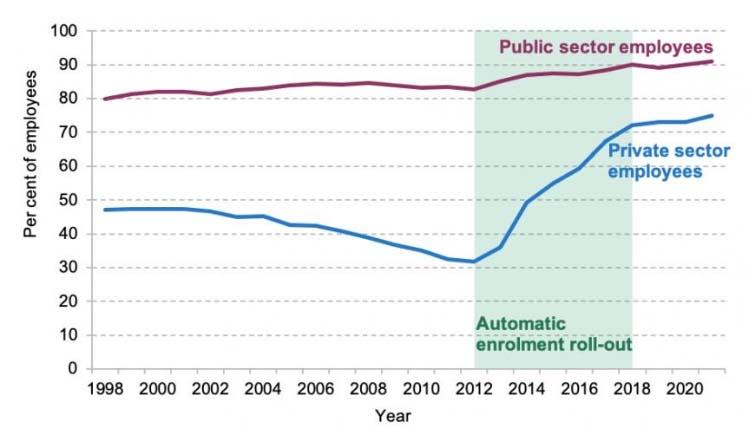

Pension participation in the UK private sector was declining steadily through the early 2000s. As illustrated in Figure 1, private sector pension membership fell from 47% in 2000 to 32% in 2012. Automatic enrolment, which was first introduced for large employers in October 2012 and gradually rolled out to apply to all employers, has been enormously successful in increasing private sector pension participation rates and reversing the declining trend. By 2018, 72% of private sector employees were participating in a workplace pension, and since then it has edged up further to 75% in 2021. The number of eligible private sector employees saving into a workplace pension increased from 5.9 million in 2012 to 14.4 million in 2021, with the total annual workplace pension saving by this group increasing from £42 billion to £62 billion over the same period.

Figure 1. Workplace pension participation

Source: Cribb and Emmerson (2016), updated with more recent data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings.

Cribb and Emmerson (2016) found that automatic enrolment increased participation much more among groups that had lower levels of participation to begin with, such as lower earners and younger age groups. In other words, while before automatic enrolment there were large differences in participation rates between different groups of workers, over the last decade these gaps have largely disappeared.

The flipside of the very widespread and consistent effect of automatic enrolment on pension saving is that it has also increased pension saving among people for whom this might not be appropriate in the short-term. Bourquin et al. (2020) found that before automatic enrolment, only 26% of those who appeared to be very financially vulnerable (e.g. being in the lowest income decile, not being able to afford essentials, having less than £1,500 in liquid savings) were saving into a pension, whereas among a group who appeared to be very financially secure, 72% were saving into a pension.1 However, after automatic enrolment, the pension participation rates for both of these groups were above 90%, which means that more than 9 in 10 of even the most financially vulnerable individuals were foregoing higher take-home pay today in order to pay into a pension. While opting out of pension saving will mean foregoing employer contributions, it could at least temporarily benefit financially vulnerable individuals, especially if it allows them to build up liquid savings, repay debts, or keep up with bills. This is likely to be the case for even more people this winter, given the current cost of living crisis.

While some workers may be better-off not saving into a pension at least in some periods, there are other groups that currently fall outside the eligibility criteria of automatic enrolment who could benefit from private pension saving. Perhaps the most concerning group is the around 5 million self-employed individuals in the UK. Crawford and Karjalainen (2020) show that only 16% of self-employed individuals were saving into a private pension in 2018, compared with 48% in 1998. They also find that pension participation fell most rapidly among those self-employed groups who, in the absence of non-pension saving, will see a significant decline in their standards of living in retirement, such as high earners and the long-term self-employed.

Looking beyond participation

A key factor in determining standards of living in retirement is the level of contributions made during working life. Since 2018 the automatic enrolment minimum employee contribution rate has been 4% of qualifying earnings2 , and evidence shows that majority of workers brought into workplace pension schemes as a result of automatic enrolment are contributing around this amount (DWP 2020).

In addition to low contribution rates when employees join a pension, Crawford and O’Brien (2021) also find that contributions tend not to increase significantly with age. There is increased concern around whether the current default contribution rates are enough to ensure adequate standards of living in retirement for savers, especially as IFS modelling finds that rather than saving a constant rate over time, individuals may be better off saving less in a pension earlier on in their career, and placing much more in a pension in later working life when their earnings are higher and they have fewer other financial commitments such as dependent children and student loan and mortgage payments (Crawford, O’Brien and Sturrock 2021). Based on this research, policies that result in saving rates that increase with age and earnings might be a better way to help ensure that individuals are saving appropriately, rather than policies that attempt to increase saving rates across the board.

What next for automatic enrolment?

While the success of automatic enrolment in encouraging pension participation among private sector employees has been undeniable, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) continues to assess options for future changes to the policy. The Government’s 2017 Automatic Enrolment Review recommended lowering the age threshold for automatic enrolment from 22 to 18, and abolishing the lower earnings limit of qualifying earnings, so that contributions would be payable from the first pound of earnings (rather than the current level of £6,240, meaning an additional £500 of saving per year for many eligible employees), by the mid-2020s. This ambition was further confirmed last year by the (then) pensions minister, but these changes are yet to be legislated. The current high inflation environment is likely to make the expansion of automatic enrolment even more difficult to implement, as boosting saving will doubtless be easier in times when living standards are rising. But ministers – like individuals – should be wary of continually pushing back when additional saving is to happen.

Despite its success in bringing people into private pension saving, the job of automatic enrolment is far from done. Implementing the 2017 review recommendations would be a start, although there might be smarter – or perhaps additional – ways in which automatic enrolment should be extended; most obviously by trying to increase saving when individuals’ earnings are relatively high and their living costs relatively low. Further progress on how best to help other groups – in particular the self-employed – is also needed. These areas should be high on the agenda of the newly appointed pensions minister Alex Burghart.