Paul Johnson, IFS director, said in response to today’s announcements:

“Today’s announcements constituted a Budget in all but name. £14 billion of tax raised through a supposedly new tax, equivalent increases in spending on health and social care, and an announcement of spending totals for the next three years certainly constitute a major fiscal event. After a quarter century of dithering we may finally have settled on a solution for improving the structure of social care funding, as well as an increase in the amount spent publicly on it. We have a funding package for the NHS which should be enough to prevent post pandemic waiting lists from spiralling. For “unprotected” departments, the announced spending totals might be enough to avoid cuts, though this is far from certain and depends on the extent of future virus-related spending.

A levy of 1.25% on employee earnings and on employer wage costs (so a 2.5% overall increase in the tax rate on earnings), will raise £14 billion a year. The extension of this levy to those over state pension age and to dividends is welcome, but this remains a tax which will be overwhelmingly borne by workers with very little coming from pensioners. This continues a trend seen over many decades of the burden of tax being shifted towards earnings. The creation of an entirely new tax will mean yet more quite unnecessary complexity.

Both spending and tax will ratchet upwards over the next few years. Taxes will reach their highest sustained level in the UK. This was always going to be an inevitable consequence of ever growing demands on health and social care, and would have happened eventually irrespective of the pandemic.

It is disappointing that the government did not find a better package of tax measures to fund these spending increases. A simple increase in income tax would have been preferable. But overall much needed reforms to social care are being introduced and unavoidable pressures on the NHS are being funded through a broad based and broadly progressive tax increase. That is better than doing nothing.”

NHS funding

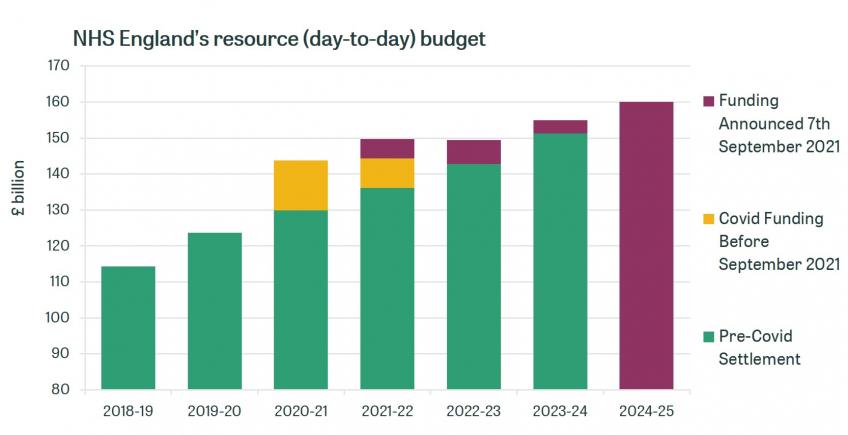

Today’s announcements include an additional £11.2 billion for the Department of Health and Social Care in 2022−23, and £9.0 billion in 2023−24. Of that, around £1.8 billion each year is earmarked for social care (discussed below).

That leaves around £9.4 billion of additional funding in 2022−23, and £7.2 billion in 2023−24, to deal with health-related Covid pressures.

Our best estimate, based on detailed analysis to be published later this week, is that this could be enough to meet the pandemic-related pressures on the NHS. If the NHS can in fact boost capacity to 10% above the level assumed in the long-term plan, as promised today, we estimate that this should be sufficient to return the waiting list to pre-Covid levels within three or four years. But even with extra funding, a boost to capacity on that scale will still be highly challenging, given long-standing staffing shortages and the potential need for ongoing infection control measures.

The settlement also includes a stated £5.6 billion of ‘additional’ funding in 2024−25, though this assumes that NHS funding would otherwise have stayed flat in real terms. The top line is that between 2018−19 and 2024−25, the NHS England budget will have increased by the equivalent of 3.9% per year in real-terms: slightly above the long-run average of 3.6% growth in UK health spending, and well above the 1.2% per year seen between 2009−10 and 2018−19, but below the average 6.0% seen under the Blair and Brown governments.

Max Warner, a Research Economist at the IFS, said:

“Today’s announcement represents a substantial increase in funding for the NHS − though in the face of enormous pressures. This additional funding could be enough to meet the Covid-induced pressures on the NHS in the near-term, and to clear the elective backlog over the parliament. This depends crucially, though, on the ability of the NHS to increase treatment volumes in the face of staffing and other capacity constraints, and on the future course of the pandemic.”

Source: HM Treasury’s PESA 2021, DHSC’s 2020-21 Revised Financial Directions to NHS England

Note: NHS England budget excludes many areas of Covid spending such as Test and Trace and PPE

Social care reform and funding

Today’s announcements include major long-term social care reforms and specific medium-term funding increases for adult social care services.

By way of long-term reform, the government has resurrected the Dilnot Commission’s proposals: from October 2023, the amount anyone will have to pay for social care over their lifetime will be capped at £86,000.The upper asset threshold above which people will have to fund their care costs in full (up to the cap) will be increased from £23,250 to £100,000. This will provide some welcome insurance to those facing the highest care costs, and makes the means-testing of support significantly more generous.

Following the backlash that plans to count people’s main residence in the means test for all types of care generated in the 2017 election, the government has confirmed it will continue to be counted only for those going into a care home and without a partner. This means those who have more of their wealth in financial assets will continue to be penalised relative to those whose wealth is in the form of their main home – even if the latter’s wealth is much more in total.

The government has not said how much it expects this ‘cap and floor’ scheme to cost, but it can be expected to be several billion pounds a year.

In terms of medium-term funding, a total of £5.4 billion will be provided to adult social care services between 2022–23 and 2024–25, to support the social care workforce (with improved training and mental healthcare, for example), improve services and signposting for informal carers and care recipients, and begin the roll-out of the longer-term reforms.

At an average of £1.8 billion per year, this funding boost is equivalent to around 9% of what councils spent on adult social care services in 2019–20. However, the early-to-mid 2010s saw big cuts in spending, despite an ageing population and rising numbers of people with learning disabilities. And as a result, adult social care spending per person was 7.5% lower in real-terms in 2019–20, the latest year for which we have data, than in 2009–10.

How funding for social care will evolve in the next few years will also depend on the wider local government funding environment. In recent years, councils have been able to increase council tax by an extra 2 to 3 percentage points if the revenues are allocated to social care: will that continue? And even if the new funding is formally ring-fenced for social care, will councils shift some of their existing funding to other services if their wider funding situation is still difficult?

While the precise path for spending – and hence for the availability and quality of care – is unclear, it is clear that the extra funding will not be sufficient to reverse the cuts in the numbers receiving care seen during the 2010s. Thus, while more people will become entitled to financial support as a result of the reforms planned, many people with care needs not considered severe enough will continue to miss out.

Kate Ogden, a research economist at the IFS said:

“The government has finally announced the main elements of its long-term plan for adult social care. These will provide more insurance for those facing the highest care costs, and a more generous means-test. More funding is also confirmed for the medium-term too. But this follows on from big cuts in spending and hence service provision during the 2010s - which the new funding will be insufficient to fully address.”

Spending Review announcement

The government has also confirmed today that a full Spending Review (SR) will be held alongside the Budget on 27 October, and published its overall spending ‘envelope’ – the total pot of money to be allocated between departments at the SR. These new spending plans cover 2022−23, 2023−24 and 2024−25 and represent a welcome return to multi-year budgeting.

The Chancellor has topped up his previous plans by around £14 billion in each year – the (gross) amount raised by today’s announced tax rise. Public service spending will increase at an average real rate of 3.2% per year over the SR period, versus 2.1% under previous plans. That will fund a substantial increase in health and social care funding, but will still leave overall public service spending £2 to £3 billion lower each year than what the government was planning to spend pre-pandemic.

Importantly, after accounting for the additional funding promised to health and social care, pre-existing commitments on schools, defence and overseas aid, and the Barnett formula, these plans still suggest a tight settlement elsewhere – at least in the short-term. The remaining, unallocated budget line – which would include not just ‘unprotected’ areas like local government, justice and further education, but also any additional virus-related spending – would be virtually flat for the first two years. These spending plans are more generous than those previously pencilled in, but still no bonanza.

The government’s plans are predicated on the assumption that the (substantial) virus-related top-ups to the NHS budget will be temporary in nature, and that funding can be channelled into social care later in the parliament. This is possible, but history teaches us that the NHS budget only tends to go in one direction: upwards. NHS spending plans are almost always topped up. In fact, since the early 1980s, the health budget has on average grown 50% (1.4 percentage points) faster than originally planned. If the government is serious about achieving a step-change in the quality of our social care system, it will need to ensure that the NHS doesn’t permanently gobble up all of the money raised by today’s tax rises.

Ben Zaranko, a Research Economist at the IFS, said:

“The Chancellor announced today a top-up to previous spending plans of around £14 billion per year. By setting his overall spending envelope alongside a new NHS and social care settlement, the Chancellor has revealed what sort of funding environment other departments can expect over the next few years. The answer is, a tight one. Given existing commitments on areas like schools, defence and overseas aid, other areas can expect their budgets to remain broadly flat over the next two years. If substantial virus-related spending needs to be funded from within these totals – for instance to bail out rail operators – then some areas could even be facing cuts.”

Tax rises

Tax revenues will reach highest ever share of national income

Today’s announcements will mean higher tax and higher spending, to the tune of around £14 billion per year. The pandemic is expected to result in a permanent increase in the size of the state – as happened after WW1 and WW2, but not after the global financial crisis. Coming out of the pandemic, government spending appears set to come out of this crisis at 42.4% of national income, higher than it was prior to the pandemic.

Following a rise in income tax of £8 billion and in corporation tax of £17 billion in the March Budget – the biggest tax rising Budget since Spring 1993 – the Chancellor has announced a further tax rise of £14 billion or 0.6% of national income, which if delivered will raise the tax burden in the UK to the highest-ever sustained level.

Isabel Stockton, a research economist at the IFS, said:

“Following just six months after the March Budget, itself the biggest tax-raising Budget since Norman Lamont’s 1993 Spring Budget, today’s announcements push taxes to their highest-ever sustained share of the economy. Equivalently, government spending is set to reach a record peacetime level. Long-term challenges around rising costs of health and social care means this increase in the size of the state is likely here to stay.”

Note: National accounts taxes shown.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Public Sector Finance databank, obr.uk/data

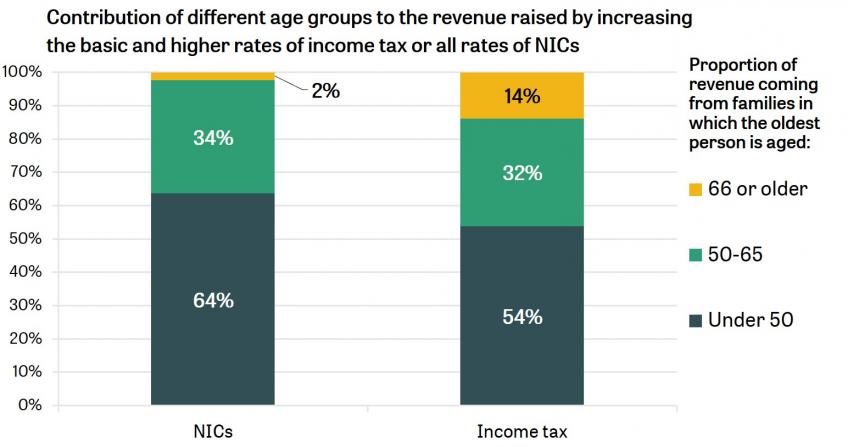

Pensioners will still contribute a very small amount towards the health and social care levy

Even with the social care levy being applied to those over State Pension Age, only about 2% of the overall tax rise comes from pensioner families, with about two-thirds coming from families aged under 50. This is because pensioners get the substantial majority of their income from private or state pensions, which the new levy will not be applied to. An equivalent increase in income tax – which state and private pensions are subject to – would have shifted more of the burden towards older families.

Note: Ignores the increase in dividend taxation. 'NICs' bar includes applying a 1.25% NICs rate to those above State Pension Age

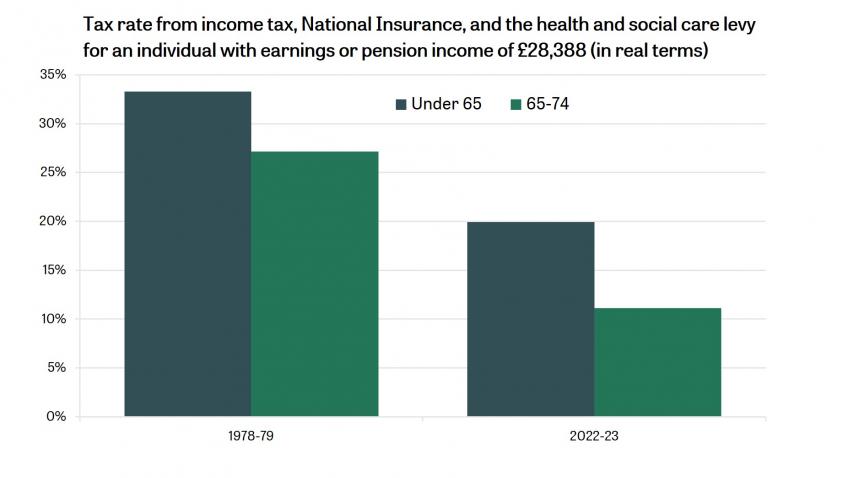

Today continues a long run trend of taxes being shifted towards working age earnings

A working-age person with average pre-pandemic earnings (£28,388) will now pay 20% of their income in income tax, NICs, and the new levy. By comparison, a pensioner receiving the same amount in pension income will pay just 11% – almost half the rate of the working-age employee. This is the continuation of a long run trend of shifting the burden of taxation towards working-age earnings: back in 1978–79 the equivalent figures for individuals with the same (real) level of income were 33% and 27%.

Tom Waters, a Senior Research Economist at IFS said:

“The overwhelming majority of the tax rise will fall on working-age individuals, a consequence of using National Insurance rather than income tax to raise the revenue. This is the latest in a long line of reforms which have tilted the burden of taxation towards the earnings of working-age people and away from the incomes of pensioners.”

Note: The ‘under 65’ bar shows the amount of tax paid on earnings; the ‘65-74’ bar shows the amount of tax paid on pension income. In both cases the income is £28,388 (average earnings pre-pandemic 2019-20). For the 1978-79 bars incomes are put in 1978-79 prices.

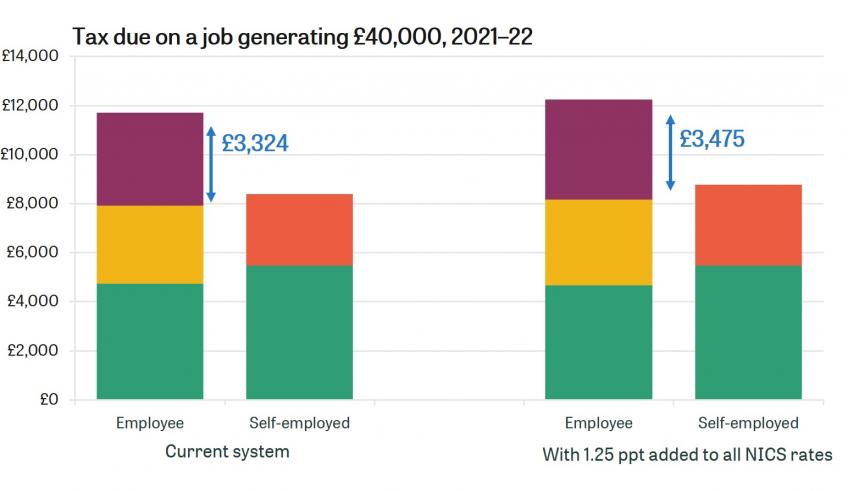

The penalty on employment relative to self-employment will grow

Incomes of the self-employed are already taxed more lightly than those of employees. Most notably, this is because there is no equivalent of employer NICs levied on the self-employed.

Under the changes announced today, the gap will grow.

The combined NICs rate on employment income (including employer NICs) will rise from 22.7% to 24.6%. The rate on the self-employed will rise from 9% to 10.25%.

Helen Miller, Deputy Director at the IFS, said:

“Levying lower rates of tax on the incomes of the self-employed than of employees is unjustified, unfair and inefficient. Today’s NICs increases increase the gap and therefore move the tax system further in the wrong direction.”

A new tax is unnecessary and adds complexity

The new ‘Health and Social Care levy’ will effectively be a third income tax. The changes could have been realised much more straightforwardly through changes to NICs (including to levy some NICs on earnings above the SPA) and to the rate of income tax charged on dividends. Adding a new tax will unnecessarily add additional complexity. The government has been clear that the revenues will be used for health and social care funding – but this is a weak form of hypothecation. The revenues raised from the levy are small relative to the overall amount spent on health and social care. There is no real sense in which the amount actually raised through the health and social care levy will affect the total amount spent on health and social care in years to come.

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director at the IFS, said:

“There is no good economic reason to introduce a third tax on income. The government could have easily achieved its aims without adding the complexity that comes with having a third tax. In the short run, the additional revenues may be spent on boosting spending on health and social care. In the longer-run, the hypothecation is an illusion.”

What do the announcements mean for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?

The short-term increases in NICs and longer-term new health and social care levy will apply in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as England, contributing around £1.9 billion a year to the £14 billion a year raised across the UK. The devolved governments will also receive additional funding via the Barnett formula as a result of the higher funding for health and social care in England – between £1.7 and £2.1 billion a year over the next 3 years. Together with their share of the UK-wide health spending on things such as vaccines, the UK government estimates that around £2.2 billion a year of spending funded by the tax rises will go to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The fact that they are set to receive more in funding than their residents pay in tax reflects the fact that earnings in the devolved nations, and particularly Wales and Northern Ireland, are lower than in England.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland operate their own health and – more generous – social care systems. Ordinarily, they would be free to spend any funding they receive via the Barnett formula as they see fit, no matter how it is spent in England. However, the Prime Minister said that “we will direct money raised through the levy to their [i.e. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland’s] health and social care services”.

To do this, the devolved governments will be required to allocate the funding they receive as a result of the levy to the NHS in the same way that they are currently required to allocate funding they receive that is formally from the part of the National Insurance contributions earmarked for the NHS. However, the levy will fund only a small proportion of health and social care spending in the devolved nations – around 6%. This means that the devolved governments could cut how much of their other non-ringfenced funding that they allocate to health and social care if they so wished, to use some of the proceeds of the levy to fund other services or to cut devolved taxes.

The only way the UK government could stop this is if it were to take control of how much of their other funding that the devolved governments allocate to health and social care services. This would be a big change to existing devolution arrangements, significantly reducing the budgetary autonomy of the devolved governments, given that taken together, health and social care amount to more than half of their spending.

David Phillips, an associate director at the IFS said:

“The prime minister has said that the funding the devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland receive as a result of the health and social care levy will be “directed” by the UK government to health and social care services. However, the devolved governments will still be able to control how they allocate their other funding Therefore they could shift some of this to other services if they so wish – which they might do given that their social care systems are currently more generous than that in England. The only way the UK government could ensure the proceeds of the health and social care levy were used in full to fund increased health and social care spending outside England would be to take much greater control of the devolved governments’ budgets - something the devolved governments would be fiercely critical of.”

Note: This has been edited to correct an error in the previous version around the compensation for employer national insurance contributions in the DHSC budget.