In 2022, governments across Europe faced a crisis as mounting tensions with Russia caused energy prices to soar. Governments scrambled to assemble relief packages to help households and businesses cope with the sudden spike in their energy bills. The cost of this support was enormous: by the end of 2023, European governments had collectively spent around €650 billion on a combination of price subsidies, cash payments and energy bill discounts.

What can we learn from this episode about designing relief packages for households? This is a pressing question. Volatility in energy markets means that supply shortages and spikes in inflation are common (think of the oil shocks of the 1970s and 1980s) and are likely to recur in the future. In such crises, governments typically face a challenging trade-off. Price subsidies ensure that the support households receive is proportionate to their energy use (and so, less directly, their energy needs). However, subsidies also reduce households’ incentives to cut back on energy use at a time when supplies are scarce. An alternative, promoted by organisations such as the International Monetary Fund, is to provide targeted cash payments to households most negatively affected. These payments, being independent of energy use, preserve incentives to reduce consumption. However, energy use can vary significantly even within income groups. Support payments that fail to account for households’ circumstances – such as family type, health and disability – risk leaving many households significantly out-of-pocket. The difficulty of targeting support becomes more acute when assistance must be rolled out quickly, leaving little time to assess how vulnerable different households are to price rises.

Perhaps for these reasons, the UK opted for a combination of universal transfers (in the form of ‘rebates’ on households’ electricity bills through the ‘Energy Bills Support Scheme’, EBSS), additional income support for recipients of various state benefits, and an energy price subsidy (the ‘Energy Price Guarantee’, EPG). The sums involved, and thus the costs of getting things wrong, were large: the total cost of the EPG and energy bill rebates in 2022–23 was 1.3% of annual GDP – equivalent to two-thirds of the UK’s defence budget. The bulk of this cost was due to the EPG, which provided significant subsidies. From October 2022 to March 2023, for every £1 households spent on energy, the government paid 64p in subsidies.

In our new paper, we study the impact of the crisis on households, how the UK’s policy responses mitigated household losses, and how alternative policies would have performed. We have three main findings.

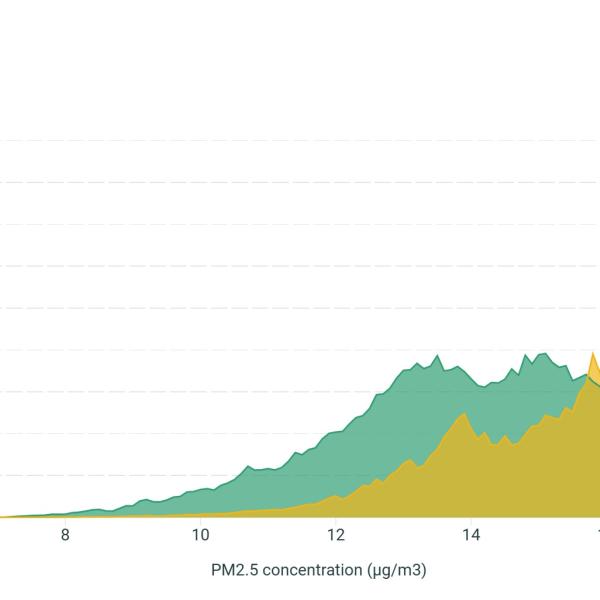

First, we find that energy consumption is sensitive to price and therefore affected by subsidies such as the EPG. In April 2022, an increase in the UK’s energy price cap, which set the price of energy for nearly all consumers at the time, led to a 45% rise in the real price of residential energy. Using bank account data, we find that this price increase resulted in a near-immediate 14% average reduction in households’ seasonally adjusted energy consumption. This implies an average price elasticity of energy demand of 0.3.

Second, the way that transfers were paid to households affected how they were spent. Households prepaying for their energy received the £400 energy bill rebates over Winter 2022–23 as vouchers (for traditional meters) or as automatic top-ups (for smart meters). Most households would have spent more than £400 on energy over this period in the absence of the rebates. This means the payment did not directly incentivise households to spend more on energy than if they had received the same amount as cash. However, prepayment households spent a much larger share of the rebate on energy – 33p of every pound of transfer – compared with a non-energy-related cash payment, which increased energy spending by only 4p for every pound transferred. Economists refer to this phenomenon as a ‘flypaper effect’, so-called because the ‘money sticks where it hits’. In contrast, we do not find similar flypaper effects for those paying for their energy via direct debit. This difference may be because receipt of these energy rebates was less salient for these households and less directly associated with their energy spending.

Armed with these findings, we then turn to analysing the performance of the government’s response to the crisis. The two main support measures – the EPG and the energy rebates – significantly reduced average household losses, from 6% to 1% of income. The measures also prevented 2.3 million households from falling into energy poverty.

However, as discussed above, the UK government faced a trade-off in limiting the losses households experienced for a given level of public spending. Allocating a greater share of funds to subsidies reduces the number of households experiencing very large increases in their energy bills. But it also encourages households to consume more energy, driving up the overall costs of the support package. As a result, larger energy price subsidies would have reduced the inequality in household losses but, at the same time, led to higher average losses overall.

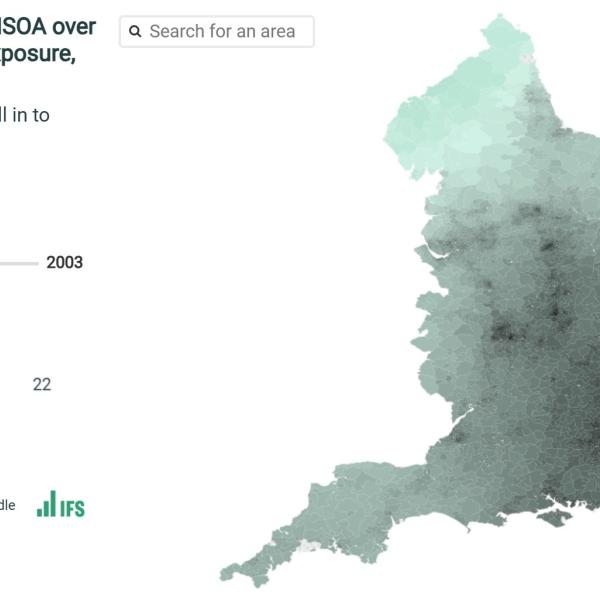

We show that two key changes to policy could have improved the government’s ability to navigate this trade-off. First, providing transfers in way that avoided the flypaper effect would have eliminated one source of inefficiency. Second, improving the targeting of income support, by basing it either on household income or, even better, on both income and households’ historical energy usage, would have been more effective. This latter approach, adopted by countries such as Austria and Germany, reduces reliance on subsidies to support the heaviest energy users. As a result, it less strongly incentivises energy consumption and therefore frees up more money to be provided in the form of non-distorting cash payments. Crucially, we find that replacing the EPG and EBSS with a better-targeted set of transfers that did not entail flypaper effects could have achieved similar outcomes in terms of both households’ average losses and losses for the most exposed households while still saving the government £4.5 billion.

Subsidising energy costs might appear at odds with many governments’ aspirations to achieve net zero carbon emissions. However, the reliance on subsidies over the energy crisis reflects the government’s inability to directly target payments to households with higher and less easily adjustable energy needs. In future crises, this challenge could be mitigated if the government were better able to integrate information from various sources to assess households’ vulnerability to shocks. Such an approach could also help address inequalities arising from policies such as raising energy taxes to meet carbon reduction targets.