Next year the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) will publish its first report examining the long-term sustainability of the Scottish Government’s budget if Scotland remains part of the UK. This week it published two papers kicking off this work: a consultation document, asking for feedback on its proposals for the report’s scope and methods; and an initial analysis of the implications of Scotland’s long-term demographic trends and medium-term outlook for income tax revenues.

In this commentary I briefly assess the SFC’s proposals, and argue that they are sensible and reflect the particular challenges of analysing the fiscal sustainability of a devolved government. I also look at what the SFC’s projections for a large fall in the Scottish population could mean for the sustainability of the Scottish Government’s finances within the UK. I find that such a fall would lead to higher funding per person for the Scottish Government than if Scotland’s population kept pace with the rest of the UK. This is because when allocating funding to the Scottish Government, the Barnett formula does not take full account of changes in population. As a result, the Scottish Government faces some tricky policy trade-offs as it seeks to both bolster long-term economic growth and improve the long-term sustainability of its finances.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission’s plans for analysing fiscal sustainability

The SFC’s consultation document provides detailed information on how it plans to analyse the long-term sustainability of the Scottish Government’s budget. The plans it sets out are sensible and respond well to the challenges of projecting the finances of a government that has to run a balanced budget, and whose funding depends to a large extent on decisions by the UK government.

First, it plans to assess the sustainability of the Scottish Government’s budget by estimating for each year of its projections the gap between funding and the amount that would need to be spent to maintain currently planned levels of provision for devolved services and social security benefits. This ‘annual budget gap’ between funding and spending is therefore a year-by-year measure of how much the Scottish Government would need to increase revenues to maintain spending, or cut spending so that it could be covered by available funding.

This approach differs from how the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) assesses the sustainability of the UK government’s finances. The OBR instead looks at how much revenues would have to be permanently increased or spending permanently cut now in order to keep debt below a given level in the final year of its projections. This summarises in a single number the action required to improve fiscal sustainability. However, such an approach would not make sense for the Scottish Government which cannot borrow or accumulate debt in the same way as the UK government. Instead, it would have to tackle any budget gap on a year-by-year basis.

Second, the SFC otherwise plans to largely mirror the OBR’s approach to projecting forwards the population, tax revenues and government spending requirements. This is important because of the key role UK government tax revenues and spending, as well as the population of Scotland relative to the rest of the UK, play in determining the Scottish Government’s funding.

For example, under the Barnett formula, the change in funding for the Scottish Government each year is equal to Scotland’s population share of changes in funding for comparable services in England (or England and Wales). And under the current fiscal framework, the Scottish Government’s net revenues from devolved taxes depend on what happens to tax revenues in Scotland relative to what happens to equivalent revenues in the rest of the UK. Using the same approach as the OBR allows the SFC to hone in on the impact of the fundamental drivers of Scotland’s funding and spending outlook – such as demographic trends or policy choices – rather than have them conflated with methodological differences between the SFC and the OBR.

Third, rather than use a single set of assumptions about spending and funding, the SFC plans to look at how the Scottish Government’s long-term fiscal outlook would differ under different assumptions about population and demographic change, and different assumptions about UK government spending decisions. Such scenario analysis (or ‘stress testing’ as the SFC calls it) is important given the big uncertainties involved in projecting 50 years ahead.

The SFC’s central projections will assume that the UK government will meet rising spending pressures in the coming decades through borrowing. All else equal, if the UK government either did not fully meet these rising costs, or met them through increasing income tax rates, the Scottish Government would receive less funding than under the SFC’s central projections, increasing its annual budget gap. The SFC’s plans for scenario analysis will illustrate how big such effects could be.

Why a falling population could be good for the Scottish Government’s finances

Population and demographic change are also key determinants of both funding and spending for the Scottish Government. The SFC plans to pay particularly close attention to analysing the impact of demographic change on the long-term sustainability of the Scottish Government’s budget in its first report to be published next year.

As a precursor to this analysis, the SFC has published an initial analysis of how Scotland’s population would change based on current trends and an assumption of zero net migration from the EU. Under these assumptions, the Scottish population would fall by 16% or 900,000 over the next 50 years. In contrast, under the same assumptions, the population of the rest of the UK is projected to be broadly flat, reflecting a higher birth rate and higher net immigration from outside of the EU.

The fall in the Scottish population would lead to the labour force falling much faster than in the rest of the UK. As a result, the SFC projects that the Scottish economy could grow by 0.5% less per year over the next 50 years than that of the UK as a whole. GDP per person is projected to grow 0.2% less in Scotland than in the UK as a whole, reflecting the more rapid ageing of the population that would accompany Scotland’s falling population.

However, perhaps counter-intuitively, the large fall in the Scottish population relative to that of the rest of the UK could be beneficial to the Scottish Government’s long-run fiscal sustainability. This is because of the operation of both the Barnett formula and the ‘block grant adjustments’ that account for the devolution of tax to the Scottish Government.

Under the Barnett formula, the Scottish Government’s funding in a given year is equal to its previous year’s funding plus its population share of the change in funding for ‘comparable services’ in England (or sometimes England and Wales). When Scotland’s population is falling compared with England’s – as it has done historically and is projected to do in the decades ahead – while the population share used for the increment to funding is updated to account for this, the funding rolled over from the previous year is not updated. This means the amount of funding received per person grows by more when the Scottish population is falling by more.

Conversely, the block grant adjustments for tax devolution are updated each year based on growth in tax revenues per person in the rest of the UK and the change in the Scottish population. What matters for Scotland’s net income from devolved taxes is what happens to revenues per person compared with the rest of the UK – if they grow faster then the Scottish budget benefits, if they grow more slowly then the Scottish budget loses out. But the Scottish budget is insulated from changes in tax revenues that reflect differences in relative population growth or decline between Scotland and the rest of the UK. As a result, only if a higher population was accompanied by higher revenues per person would the Scottish Government see its net receipts from devolved taxes rise if it stemmed population decline.

Current funding arrangements therefore benefit the Scottish Government’s budget via the Barnett formula when the population falls, and protect the budget from any population-driven shortfall in devolved tax revenues. The SFC has not yet said how important this effect could be: presumably that is coming in its first full report next year. But it is possible to get a sense of scale using some indicative calculations that broadly reflect current relative funding levels and projected population and spending growth.

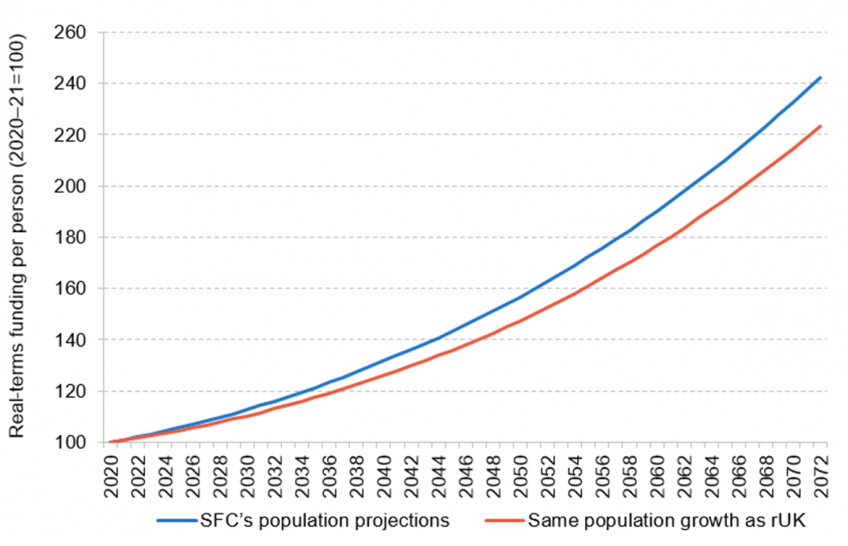

Figure 1 shows projections of Scottish Government funding per person assuming:

- Funding per person in Scotland begins at 129% of the English level. This is our estimate for relative block grant funding levels in 2020–21, excluding temporary COVID-19 funding.

- UK government spending on comparable services in England grows by 4.33% per year in cash terms, which is the average growth rate over the next 50 years for health, education, social care, capital and other departmental spending in the OBR’s central projections.

- Inflation averages 2.3% per year, again the same as assumed in the OBR’s long-term central projections.

- Scotland’s devolved tax revenues grow at the same rate per person as equivalent revenues in the rest of the UK.

The blue line shows projections for funding assuming Scotland’s population falls in line with the SFC’s central assumptions (i.e. 16% over the next 50 years), whereas the red line shows projections assuming Scotland’s population moves in line with that of the rest of the UK.

Figure 1. Projected levels of Scottish Government funding per person under different assumptions about the change in the Scottish population, adjusted for inflation

Source: Author’s calculations using SFC (2022) and OBR (2022). The figure abstracts from short-term changes in funding (including changes linked to temporary COVID-19 funding), and focuses on indicative long-term projections.

The blue line lies above the red line in all years of the projection, showing that funding per person would be higher given the projected falls in the Scottish population than if the Scottish population kept pace with that of the rest of the UK. Under our indicative projections, slower population growth would mean around 2.5% more funding per person per year by the early 2030s, rising to 4.5% more by the early 2040s, 6.5% more by the early 2050s and 8.5% more by the early 2070s. These are not insubstantial sums: to put them in context, funding for the Scottish police and fire services amounts to around 4.5% of Scottish Government spending in the current financial year.

What are the implications for Scottish Government policy?

These findings have important implications for the policy trade-offs the Scottish Government faces in the decades ahead if Scotland remains part of the UK.

On the one hand, policies that successfully attracted more migrants and boosted birth rates could play an important role in bolstering the size of the labour force and addressing potential skills shortages, including those facing Scottish public services. However, because the resulting higher population would mean lower funding per person via the Barnett formula, this could harm rather than help the long-term sustainability of the Scottish Government’s finances even as it helps the wider economy. This will make it particularly important to also focus on efforts to boost skills, productivity and incomes to increase the amount raised per person from devolved taxes, as well as efforts to tackle ill health and other drivers of demand for public services to reduce spending. Such policies, if successful, would not only do more to bolster long-term Scottish fiscal sustainability but also, of course, improve the material well-being and lives of the people of Scotland.

This situation stands somewhat in contrast to the incentives the Scottish Government would face under independence, where boosting immigration and birth rates would help address the long-run fiscal challenges facing the country. This is because the funding available to the Scottish Government would depend only on its own revenues (not those of the rest of the UK), and would be increased by the additional economic growth generated by faster population growth, a bigger labour force and a less rapidly ageing population.

This is a reminder that not only would independence allow for different policy choices – the types of policies to prioritise may also differ in an independent Scotland. As part of the UK, the Scottish Government’s budget is protected from and even benefits from falls in Scotland’s population, even as the wider economy likely suffers. As an independent country, Scotland’s public finances would instead almost certainly be stronger if population decline could be stemmed. Indeed, boosting birth rates and immigration would provide some help in addressing the significant fiscal challenges an independent Scotland would face unless it could boost economic growth.